The Racer's Edge

RACE WATCH

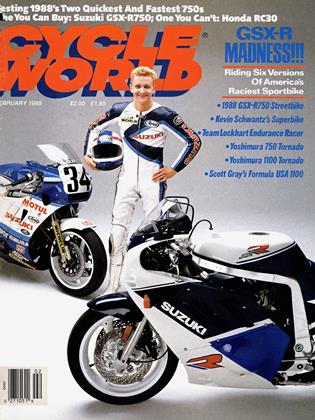

It's called desire. And Bubba Shobert knows what it is, where to get it and how to keep it

DAIN GINGERELLI

RON LAWSON

WHEN BUBBA SHOBERT FINished second at the Springfield Stroh’s Mile back in 1984, it marked perhaps the most important loss of his life. Coming into the race, Shobert trailed Honda teammate Ricky Graham by 15 points for the championship. Springfield being the final race of the season, Shobert needed at least a second-place finish to win the title-provided Graham broke down or crashed out of the race.

As fate would have it, Graham did crash on the penultimate lap of the race. Shobert, in a heated battle with Ted Boody for first place, saw Graham sitting on the sidelines, and backed off ever so slightly. As Shobert recalls, “I lost that edge that I had at all the other races. I just didn’t go into Turn Three as hard as I could have, just being extra cautious.” Caution here, so it seemed, was all the edge he needed to earn rights to The Plate.

So Shobert settled for second place at the ’84 Springfield Mile behind Boody. And as he dismounted his Honda RS750, he was swarmed by his pit crew and an army of Camel Pro Series race fans. “You’re the champ,” they shouted, “You won.” While all this was going on, Graham and his battered RS750, its left handlebar bent downward in dishonor, sputtered practically unnoticed across the finish line. Graham was then escorted to first aid, where paramedics tended to his broken hand. Then came the announcement: By virtue of his 13th-place finish and the two points it earned him, Ricky Graham was the new CPS champ, beating out Bubba Shobert by a single point.

It was one of the most dramatic moments in AMA Grand National history. And it taught Shobert a valuable lesson: Never give up.

“That gave me a drive going into the next year,” Bubba now recalls after winning his third consecutive Camel Pro Series Championship. “Maybe if I had won the championship that year, I wouldn’t have had a drive for the next year.”

What a drive it proved to be. Since that 25-lap main at Springfield three years ago, nobody else has won the AMA Grand National Championship.

But even before that spectacular 1984 Springfield Mile, Shobert had already begun an incredible string of firsts and seconds. In that season’s final 12 races, he finished first or second in all but one. 1984 also made a champion out of Shobert, even though he didn’t win The Plate: “That year taught me that I can get myself motivated when I have to,” he says. And motivation—desire, if you will—is what makes champions.

Nobody, least of all Shobert, thought he had championship material when he turned AMA Expert in 1980. In his own words, he finished “twenty-second or something in the standings” as a first-year Expert. No Rookie-of-the-Year honors, no top10 billing. Just a wiry little guy from Lubbock, Texas, trying to make it big in perhaps the toughest form of motorcycle racing in the world.

“When I was a kid,” Shobert now reflects, “I never thought I’d be as good as those guys.” But he enjoyed two advantages as an aspiring racer: the support and encouragement of his parents, and the most important ingredient of all for any racer to be a champion—desire.

“My parents have been a big help,” he says today. “My dad never pushed me. He gives advice; he’s been a big part.”

The desire? Well, Shobert knows that without it, he’d be just another racer, someone to finish “twenty-second or something.” As he puts it, “You see riders when they’re coming up, and they have the talent. As much talent as I’ve got. But they don’t have every little thing that it takes.” He pauses, finding the right phrase. “They didn’t want it bad enough.”

Wanting it bad enough, you see, is what fuels Shobert’s fire for life. Desire follows him wherever he goes. But that desire is tempered with a need to make racing fun. And Shobert does have fun. Forget about the half-million or so dollars he earns during the year from the sport. Don’t even consider that in Skip Eaken, Ray Pummel and Mike Velasco, he has six of the most gifted hands that ever touched a Class C racebike. Shobert enjoys racing no matter what the odds, what the outcome.

“When there’s a group of us racing together, and going down the straightaway, I think, ‘Man, this is neat' And it really is. There are lots of safe guys that I race with, and it’s a good feeling to know I can do this for a living.”

Few riders besides Bubba Shobert can make that statement, and still retain financial security. But Shobert knows that racing is serious business. And he treats it the way a professional should. It’s his living. And he would like to see the sport improve, as much for his financial interests as for others.

“Grand National racing has never gone anywhere,” contends Shobert. “Camel has put in a lot of money, and I’m not really sure what they’re getting out of it.” These are words, remember, from a man who won nearly a third of the $475,000 jackpot that R.J. Reynolds posted for the 1987 season. And throughout his career, he has pocketed $301,700 from Camel races.

Indeed, if motorcycle racing is ever going to step up to the big time, if one day a dozen or so racers will be able to bank where Shobert does, something positive needs to be done. And Shobert feels the solution is in television. He knows that even the coveted Number One plate that rests on the front of his Honda holds little value during his annual mid-winter quests for sponsorship. That’s because Shobert, like other AMA Class C racers, can’t promise his sponsors that their logos will be seen on television, the most-watched medium in America today.

“Sponsors almost laugh at you. You’re asking for 50, 100 thousand dollars. They ask, ‘What are we going to get out of it?’ And you can’t tell them they’re going to get anything. You could tell them that this race will be on TV, and this and that, but you’d be lying to them.” The Texan in Shobert surfaces when he says of the money mess, “It’s like getting blood out of a turnip.”

As it is now, the Camel money often spells the difference between earning a profit or ending up in the red for many top Experts. The 1987 season, which was split into two individual championships—the 18-race Camel Pro Series consisting of nine roadraces and nine flat-track races, and a separate dirt-track Grand National Championship—is a good example, claims Shobert. He points out that the non-Camel-supported Grand National races last year were a losing proposition for him, because they had no support from either Honda or R.J. Reynolds. “Last year I did a few on my own. I did fairly good. I placed well enough that I thought Ed cover my expenses. I was paying my mechanic and traveling expenses. I’d get a second at a National, and by the time I paid for all my expenses, I’d lose 500 bucks. The only reason I was doing it was to win the Number One plate. I was paving for the Number One plate.

“Without Camel involved, I don’t think there would be a national circuit. If there was one, it would just be for the fun of it; you sure couldn’t make any money.”

The crux of American motorcycle racing’s depression, Shobert feels, is the AMA. “As much as I hate to blame it on the AMA, they’re at fault for most of the causes. Why don’t we have any TV coverage? Why don’t they have anyone professional enough who can seek sponsors, to promote the thing? It’s almost like they want to keep it a backyard sport.”

It’s a backyard that Shobert doesn’t want to play in for the rest of his professional racing career, either. Like many other successful American Class C racers, he has his bags packed and his passport ready for Europe. Which is one primary reason he’s racing Superbikes in the Camel Pro Series again this year. He feels he has to spend time on road courses in America if he’s going to find a Grand Prix ride for Europe. He says confidently, “I think racing a Superbike has given me experience to ride a 500.” And if he can’t line up a GP ride, perhaps a slot on somebody’s world championship Superbike, if the series is in existence in 1989. “I would have an advantage there, coming off a Superbike here,” he says.

But landing a world championship Superbike or even a Grand Prix ride is a minor holdback for him. The real holdback is the money. Shobert couldn’t earn as much money during his first year or two in Europe as he does in America. “The last few years I’ve made really good money here. It would be stupid for me to go over there now. I probably couldn’t make half as much as I make here. I guess things like that have kept me from going to Europe.”

Shobert is maintaining a vigilance on his biological clock, and figures 1989 should be his departure time for Europe. At 25 years old, he is nearing his prime as a flat-track racer. But 25 is young for a roadracer, as Kenny Roberts proved in 1978 when, at the age of 27, he first conquered Europe. By the time King Kenny abdicated his European throne, he was 33, and still all but unbeatable.

And so, Bubba Shobert begins the 1988 AMA Grand National season as he has the past three years, with his head down and charging full speed ahead. His goal this time, though, is something even more prestigious than a fourth consecutive title. He has his sights zeroed in on Jay Springsteen’s career win record, which currently totals 40. With 32 wins to date, Shobert could catch The Springer this year. Last year he won seven races, following a slow start after breaking his thumb at the Easter Series Match Races in England.

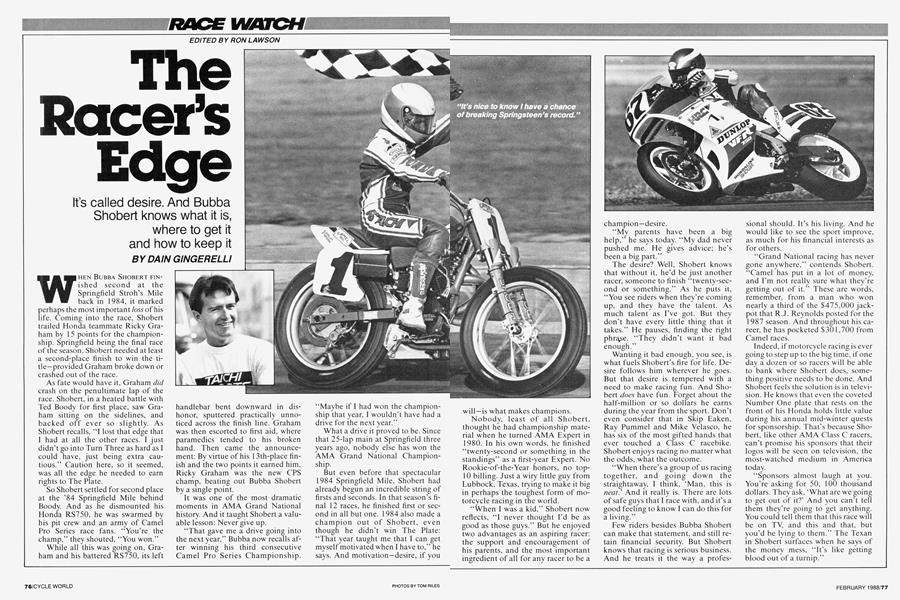

“It’s nice to know that I have a chance of breaking Springsteen’s record. I’ve always taken my racing as a business. If it’s going to cost me money to break a record, will it be worth it? Depending on how much it costs, it probably will be. I’m not that money-hungry. But I’d like my name to be connected with something like that. If you could put a price on it, I’d probably buy it.”

But Shobert knows that money alone can’t buy a win. Sure, it helps. But when it comes to laying the entire program on the line, it’s the rider with the best-prepared bike, the best pit crew and the most talent who stands the best chance of winning. And there’s one other variable for the equation—desire. The same kind of desire that has been with Bubba Shobert in at least 32 races during his fun-packed career. Desire that has made him one of the richest racers in Class C history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsBad Raps And Bad Reps

FEBRUARY 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsRaised Standards

FEBRUARY 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Allies In the Atv Wars

FEBRUARY 1988 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

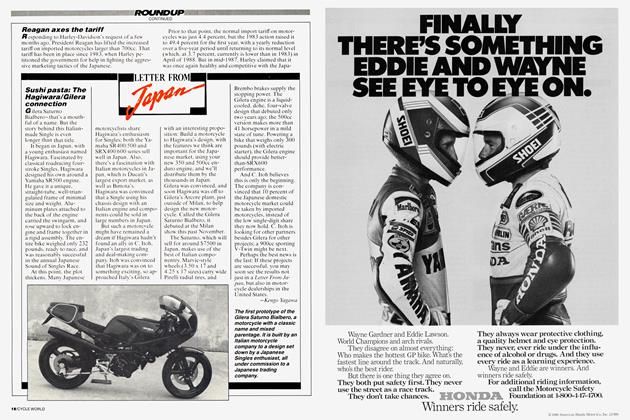

RoundupLetter From Japan

FEBRUARY 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

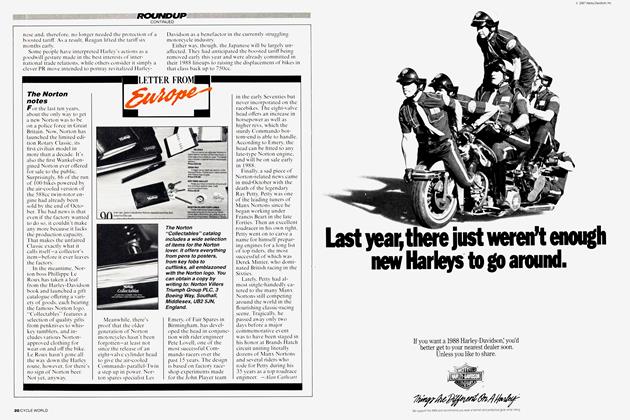

RoundupLetter From Europe

FEBRUARY 1988 By Alan Cathcart