SERIOUS AT STEAMBOAT

RACE WATCH

JON F. THOMPSON

The Incredible Adventures of Blind Faith Racing and the $200 Ducati

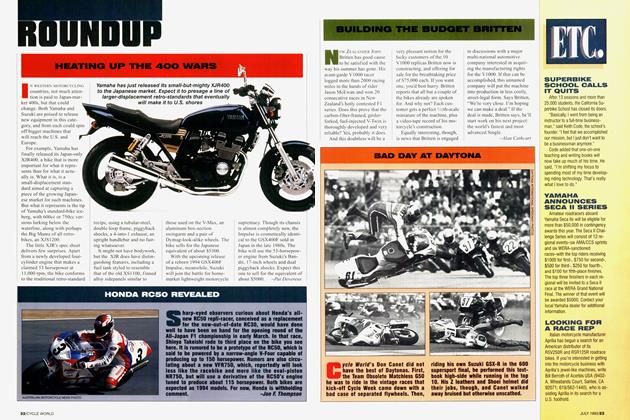

THE BIKE SITS FORLORN AND covered with oil, the victim of multiple disasters. Its engine is silent and maybe busted. Its rear wheel is askew. We ponder it for a while. Finally, we summon the energy to pull the little Duck off its stand and roll it into the truck. I look at Jim, he looks at me. We both shrug. "That's racing," we're both thinking. Panting and hot after the long push back to the paddock, all I want now is a beer. And a bath. Mostly, I want home.

“I think we’ll go vintage racing.”

A worried quiet hung over our staff meeting following this pronouncement from Mr. Editor Edwards. Was he kidding? Combat on sorry old crocks with skinny tires, no suspension and no brakes? He wasn’t kidding.

It would be a Team Cycle World attack on the Steamboat Springs vintage weekend, held each September in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. There would be a staffer for each of the AHRMA classes, from trials to roadrace tribulation.

Listen: Racing’s expensive. Years ago, when I worked for a car magazine covering racing, a Can-Am roadracer offered me the following investment tip: “To become a millionaire in racing, start with $3 million.”

I heard his message loud and clear, so I was determined to get my money’s worth out of this deal. I bulleted into Edwards’ office after the meeting to subscribe to the Sportsman 350 roadrace class. Under AHRMA’s rules, a Sportsman 350 bike is eligible for Sportsman 500. So a Sportsman 350 racer gets two races per weekend, and all the practice appropriate thereto. If he picks the right bike, he not only gets lots of laps, he’s reasonably competitive in both classes. Picking the right bike was easy. Hondas own

AHRMA 350 and 500 Sportsman racing, so any 350cc Honda Twin built before 1973 would do nicely. Then fate intervened.

Fate, in this instance, wore the cynically bemused visage of my friend Jim Miller. Jim, who otherwise displays passable mental health, is a Ducati Singles enthusiast. He has a garage full of them. Some of them run. He had a line on three more. One could be mine for $200; so cheap it was almost free, he goaded me. All I had to do was use my pickup to drive us to Tucson to retrieve them.

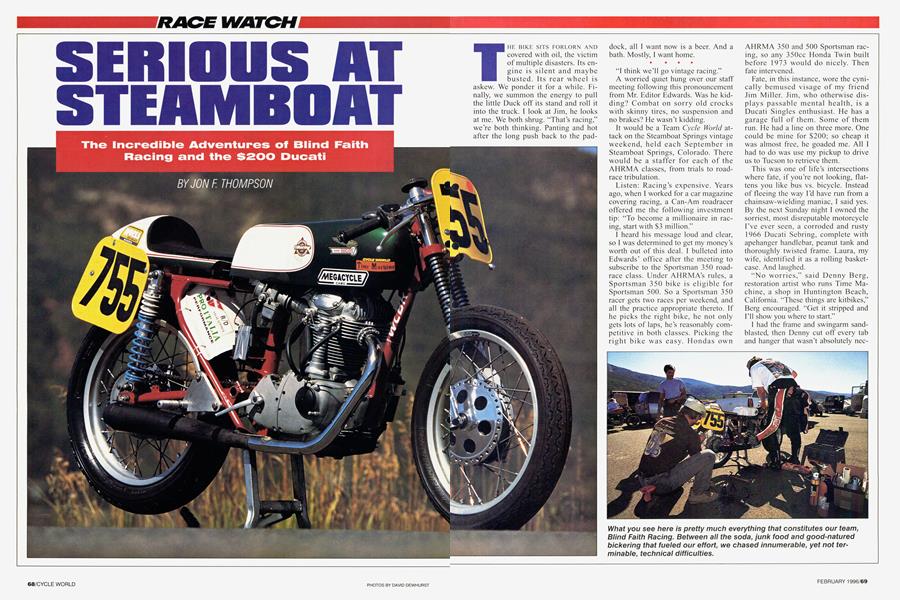

This was one of life’s intersections where fate, if you’re not looking, flattens you like bus vs. bicycle. Instead of fleeing the way I’d have run from a chainsaw-wielding maniac, I said yes. By the next Sunday night I owned the sorriest, most disreputable motorcycle I’ve ever seen, a corroded and rusty 1966 Ducati Sebring, complete with apehanger handlebar, peanut tank and thoroughly twisted frame. Laura, my wife, identified it as a rolling basketcase. And laughed.

“No worries,” said Denny Berg, restoration artist who runs Time Machine, a shop in Huntington Beach, California. “These things are kitbikes,” Berg encouraged. “Get it stripped and I’ll show you where to start.”

I had the frame and swingarm sandblasted, then Denny cut off every tab and hanger that wasn’t absolutely necessary and welded on swingarm-pivot and motor-mount reinforcements. I had both pieces straightened, then I hung them in my garage and painted them.

Now to round up some parts. Brakes? The stock front brake was junk even when new. I found a twinleading-shoe unit from a Honda CB175 that plugged right in. Denny ventilated it and the stock rear unit, then shod everything with new Ferodo lining. I had both hubs polished, and then obtained from Buchanan’s, a

Monterey Park, California, wheel specialist, a pair of 18-inch Sun aluminum rims custom-drilled for my hubs. Denny laced hubs to rims and mounted Avon Roadrunner R2 rubber. My pal Gil Vaillancourt at Works Performance in Northridge, California, built me a pair of shocks. To stay on budget (cue laughter), I retained the stock fork with its penne-pasta-sized 31.5mm tubes, but bought new chrome-moly tubes. The completed fork, revalved and assembled by Denny, now turns on tapered roller bearings, instead of its tiny original ball-bearings, for smoother, faster tank-slappers. I polished the top triple-clamp, stuck on a pair of clipons, and the bike became a roller. I added a fiberglass tank and carb-intake shield from Air Tech in Oceanside, California, and a seat/rear-fender unit from deep within the cobwebbed wilds of the CW storage shed, then had the pieces painted in a classic 1960s scallop motif by Bob’s Krazy Brush in Torrance, California.

In its prime, the Ducati Sebring was at best a placid beast. To make the engine racy and reliable, I shipped it to Mike Green at West Coast British Racing in Livermore, California. Green, successful racing his own Ducati Singles, lightened the timing gears, discarded the alternator and brought the capacity from a stock 340cc up to 350cc by boring the cylinder to take a modified piston originally intended for a Triumph 750. He ported the Sebring’s non-desmo head, installed a Megacycle cam, Ducati 900SS valves, and R/D coil valve springs and titanium keepers. Then he bolted on a custom aluminum manifold and pronounced the work done. The engine back in our hands, we added a 36mm Dell’Orto carb and topped the assembly off with an intake bell and an exhaust system from Pro Italia in Glendale, California. Potential? Horsepower in the mid-30s at about 8500 rpm, easily double a stock Sebring’s power production.

Then came many late nights in which Denny, Jim and I laughed, listened to rock’n’roll and put it all together. We bolted the engine into the chassis, using high-grade hardware to make sure it stayed there. We installed sprockets and chain, battery and totalloss ignition system, put seals and fluid in the fork, mounted the bodywork and exhaust, finished off the hand controls, made the foot controls-the latter painstakingly fabricated by Berg-and lock-wired everything that moved. Finally, we had an authentic 1960s-era vintage racer we’d pretty much built ourselves.

But would it work? We hauled it to a Willow Springs Raceway practice day to find out. The little Duck started first try, its megaphoned exhaust note loud enough to wake the Brothers Ducati from their eternal slumbers. Steering, brakes, controls, all okay. We cranked off maybe 15 easy, lowrev laps of Willow’s short “Streets” circuit, seating rings, bedding-in brakes and generally getting the feel of the bike. The Blind Faith Racing Ducati was as ready as it was likely to get, which is not to say done. Racebikes never are truly done. But things were looking up, and my tension levels, red-lined for weeks as the project lagged behind schedule and soared over budget, began falling.

Time to check on the progress of the other CW staffers: No progress at all. Everybody, in fact, has bailed. “Next year,” promises Mr. Editor Edwards, his own 1970 Kawasaki HI still in need of engine attention. So, The Great Steamboat Springs Vintage Adventure is down to Jim and me. Fine. We load up and commence the 1018-mile trip from my house to Steamboat with a truckload of racebike and a weird mixture of high spirits and apprehensions.

Main apprehension: Will it pass tech? Good question. Tech guys love new racebikes. They comb over them with fine-toothed nit-picks, looking for rule contraventions and unsafe conditions, real and imagined. So just in case we have to fix stuff, we’re among the first in line for Friday’s tech session, tools at the ready. We slide through like we know what we’re doing, receiving congratulations from John Goodpaster, AHRMA’s chief tech inspector, for presenting such a tidy and well-prepared racebike. Yes!

We high-five, then set about learning the course. It’s laid out on the hilly streets of ski-resort Steamboat’s condoland with maybe 200 feet of elevation change. Corners are either really fast or really slow-the fastest part of the track, the downhill start-finish straight, leading to the slowest corner, a 120-degree left. There’s just one mediumspeed turn, Corners 3 and 4, which the racers arc in a single radius. The streets are steeply crowned and lined with curbing, the two fast Carousel sweepers are studded with manhole covers, and the six intersections we’ll race through are bumpy. We take several

laps in the truck, and then walk the 1.6-mile course. Tomorrow we do it for real-first in three 15-minute practice sessions, then in two eight-lap races.

Practice starts at 8 a.m. I sleep poorly, and am awake for good at 5. Buzzed by coffee, we’re in the paddock at 7, ready at 7:45 and rolling at 8 sharp. The first session I take easy, trying to figure out the track.

We go leaner with our jetting, then go out for the second session. I crank up the speeds. The chassis is working well at the rear, but the front is chattering through the right-hand Carousel. Tire-pressure adjustment helps. Unfortunately, nothing helps the engine. At peak rpm, sometimes it acts rich, sometimes it acts lean. Back in the pits at the end of the session, we’re confused. Also, we’re concerned. Oil is pouring out through the countershaft seal on the right, and out of the clutchinspection cover on the left. Nothing we can do with the former. We hit the latter with a bead of silicone sealer and hope for the best.

We leave the jetting alone for the final session, yet things seem better. In spite of a yellow in one corner, I easily equal my fast laptime in the previous session. Two hours to my first race. I fidget, cleaning rag in hand, working with a spray can of what photographer David Dewhurst informs me is “nervous-racer’s polish.” Butterflies.

Finally, the 350 Sportsman race is called to the line. We pregrid, take a lap, then line up. I start eighth, on the outside, perfect for staying out of trouble in that acute first corner. We get the oneminute sign, then the half-minute. Revs up. Clutch in. Click into gear. Then the green. I get a good start, take it easy through the first few corners, and then settle in to try to do some good. I stay out of trouble, but the bike still isn’t running cleanly. I spot Dewhurst on the inside of Turn 2. As I pass his position and get on the power, the rear-end takes a vicious snap outside. I catch it, but a guy passes me. Phew. The bike is feeling wonky and won’t pull at full throttle on the most important part of the track-up the long hill leading to the fast right-hander that feeds onto the startfinish straight. But next lap I pass a guy under braking in Turn 2. Then the

checkered flag. I finish seventh behind a few Hondas and Ducatis. Also, ahead of a few Hondas and Ducatis.

Back in the paddock, frowns and dark looks. There’s oil everywhere, mostly from the countershaft seal, but also from the clutch cover and cylinder base gasket. Nothing to be done. That’s not our only problem. The right-side chain adjuster stripped during the race and allowed the right side of the axle to skew forward; that’s what put the bike sideways. The chain is at full-droop, the wheel cocked to the left. Is the adjuster stripped irreparably? Jim thinks maybe not. He catches some threads with the nut, tightens the chain, realigns the wheel and torques everything down. We shall see.

Too soon the 500 Sportsman race is called to the pregrid, where the bike promptly stalls. It’s been easy to start, but this time it isn’t. When it finally does catch, it’s running raggedly. Not good. I start 13th, from the inside. I get a great jump, the little Duck popping its wheel off the ground as the clutch and engine work together to holeshot me past some guys. The first lap goes fine-I short-shift, the engine still misfiring at high revs.

At the end of lap two, I’m braking hard at the end of the start-finish straight, coming up fast on another rider. I go outside. The rider moves over on me. We bang handlebars, legs and footpegs. We do it again, bouncing off each other. I slip past, amazed neither of us fell. I get through Turns 1 and 2, and shift up through third gear hard on the gas, heading for Turns 3 and 4.

And the engine just quits. I throw my hand in the air and coast to a stop outside Turn 3, the lowest part of the racetrack and the farthest from the pits. I wait for the race to conclude, then, with some help, push the bike back to the paddock.

We look it over. Jim mutters a quiet, disgusted expletive. The intake manifold is broken right at a weld, all the way around. The carb is hanging by safety wire, fuel line and throttle cable. If the manifold cracked early on and worsened as the day progressed, the resulting intake air leak is why we chased our tails as we tried to get the jetting right, and why the bike ran so poorly. Was it sucking so much air, finally, that it burned a valve? I doubt it, as the exhaust header wasn’t discolored by excessive exhaust temperature. We’ll see when we yank the head. Also, the chain adjuster has stripped again. Real lucky I didn't fall.

When it’s over, we’re classified 15th. Another racer had the good grace to fall before our little Duck stopped, so we’re not dead last. But here’s the thing: Honda 450-mounted Kat Kovacs, with whom I banged handlebars, finished sixth-Jim accuses me of being willing to beat up girls to make a pass-and Ducati 350-mounted Stuart Carter, who passed me when my bike went off-song, finished fifth. Ah, what might have been.

And that’s what Jim and I are left to ponder on the long flog back to Los Angeles. We talk about books and married life, about differential equations and Beatles concerts, about God and politics and Mozart. And we replay every move we made, all weekend long. There isn’t too much we would change.

Just outside L.A., we spot someone towing a mini-dragster powered by what looks like a CR250 engine. “Wow,” I say, “people will race anything.” I think for a minute, and add, “Even 30-year-old motorcycles.” We both laugh.

Will we do it again? Let’s just say that the Blind Faith Racing Ducati isn’t for sale. AHRMA’s relaxed atmosphere and pleasant people have infected us both. Repairs and upgrades are under way.