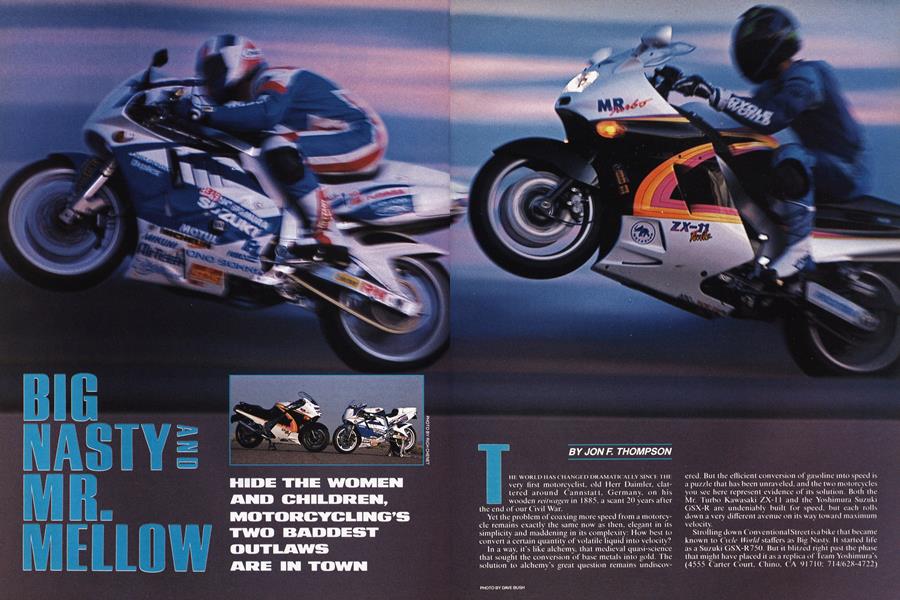

BIG NASTY AND MR. MELLOW

HIDE THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN, MOTORCYCLING'S TWO BADDEST OUTLAWS ARE IN TOWN

JON F. THOMPSON

HE WORLD HAS CHANGED DRAMATICALLY SINCE THE very first motorcyclist. old Herr Daimler. clattered around Cannstatt. Germany. on his wooden reitwagen in 1885. a scant 20 years after the end of our Civil War.

Yet the problem of coaxing more speed Irom a motorcycle relnains exactly the same now as then. elegant in its simplicity and maddening in its complexity: How best to convert a certain quantity of volatile liquid into velocity?

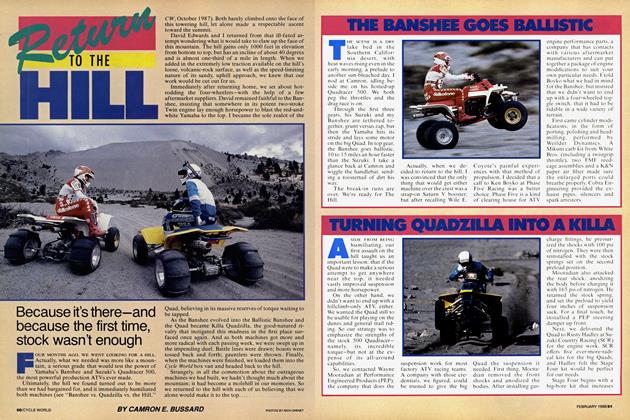

In a way, it's like alchem~. that medieval quasi-science that sought the conversion ol' base metals 111k) gold. Flic solution to alchemy's great question remains undiscovered. But the efficient conversion of gasoline into speed is a puzzle that has been unraveled, and the two motorcycles you see here represent evidence of its solution. Both the Mr. Turbo Kawasaki ZX-II and the Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-K are undeniably built for speed, but each rolls down a very different avenue on its way toward maximum velocity.

Strolling down ( 'onventionalStreet isa bike that became known to (Vc/e World staffers as Big Nasty. It started life as a Suzuki GSX-R750. But it blitzed right past the phase that might have placed it asa replica of Team Yoshimura's (4555 Carter C ourt. Chino. CA 91710; 714/628-4722) famed Big Papa Formula USA racebike, and settled instead a step beyond that as the rootin’est, tootin’est, naturally aspirated motorcycle, street or race, we’ve seen in a long while. What’s stock on Big Nasty? The frame, engine cases, transmission parts, clutch, controls and brake calipers, but not much else. Result? Well, one answer is a motorcycle with $16.267 worth of parts and labor added to its base price. The search for velocity is just as that hoary old adage puts it: Speed costs money. How fast do you want to go?

However fast that may be. Big Nasty is up to the job. right f rom the ground up. Its shoes are Michelin Hi-Sport radiais mounted upon Italian-built Tecnomagnesio wheels. Suspension is by way of a Yoshimura/Kay aba upside-down fork and triple-clamps, a Yosh Superbike swingarm assembly and related rear-suspension linkage, and an Öhlins shock. The bike came to Cycle World equipped with carbon-fiber outer fork tubes, but when one of those developed a leaky seal. Yoshimura wrench Scott Link, unable to quickly locate replacement seals, substituted an identically valved Kayaba aluminum fork.

The presence of all this specialized suspension componentry. sized to fit extra-wide tires, means that not even this bike's axles are stock items. With a few exceptions, however, all these components are off-the-shelf Yoshimura parts. The swingarm on this bike is not for sale, however. The Superbike swingarms Yoshimura sells are as heavily braced as this one, but are sized to fit standardwidth GSX-R wheels. Not standard, but sold to the public. are the bike's cast-iron front rotors, specially made for Yoshimura.

Then there's the matter of this bike’s body parts, FI race-series pieces available only in Japan. The cost, not counting the bodywork, to duplicate this chassis? The parts list totals $8201. plus tax, plus your core GSX-R.

But what makes this bike really special is its engine, a 1340cc package—81.76 cubic inches—that develops a claimed 189 horsepower, an astonishing 141 horsepower per liter. That figure is even better than it sounds, because this isn’t peaky, hard-to-manage horsepower available only within the confines of a narrow rev range situated in the rarefied atmosphere around 9000 rpm. This engine, based on Katana 1 100 components, pulls like a diesel, delivering huge amounts of power anytime the rider calls for it, at any speed, in any gear.

This kind of power production, especially from a naturally aspirated engine built to perform street duty, doesn’t come easily. Getting it requires some very specialized parts and some very specialized labor.

To build this engine, Yosh starts with the stock cases and crank. The crank is magnafiuxed and balanced, and a cylinder block containing oversized cylinder sleeves is installed. These are sized for 85mm Cosworth pistons. The cylinder head is ported and polished, and Stage Two Yosh cams—with 10mm intake and 8.5mm exhaust lift, 252 degrees of intake and 245 degrees of exhaust duration—are installed. These cams actuate stainless-steel,30mm intake and 28.5mm exhaust valves. 1.5mm oversize on the intake side and a millimeter oversize on the exhaust side. The engine also uses Carrillo rods, a heavy-duty valve-spring kit, a heavy-duty cam chain, a manual cam-chain tensioner and 40mm Mikuni carbs carrying Yosh slides. These parts, with the multiple steps of inspection, boring, honing, magnafluxing, assembly and dyno testing, brought the price of this engine to $8066, $2953 of which was for labor.

Insert this engine into that very special Yosh/Suzuki chassis, add the bodywork, and what you have is Big Nasty, ready to rumble.

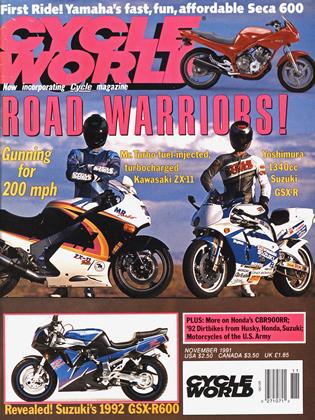

In the other corner, meanwhile, sidling down Alternative Avenue, is a bike that came to be known as Mr. Mellow. It's a Kawasaki ZX-l l. built bv Houston-based drag racer Terry Kizer. who operates a turbocharging aftermarket company called Mr. Turbo (40 14 Hopper St., Houston, TX 77093: 7 l 3/442-7 l l 3). Mr. Mellow is an alternative motorcycle for several important reasons. First of all. it’s basically stock. ("Yeah, sure.” chortle street racers everywhere.) And secondly, by virtue of its mostly stock chassis specification, where Big Nasty, with its firm suspension, high seat and very low clip-ons, was born for very aggressive cornering, the ZX is more aptly suited for all-around use.

Except for fitment of Metzeler rubber in place of the ZX’s stock Dunlop Sportmax radiais. Kizer chose to direct his time and energy toward the bike's engine. This remained stock, with two exceptions: He removed the stock Kawasaki pistons and machined just enough material from the top of each to reduce the engine's off-boost compression ratio from l l:l to about l():l. And after a rod expired during top-speed testing. Kizer fitted a set of Carrillo rods.

Kizer began his ZX project by installing a very special fuel-injection system, built for him by Martronic Engineering, Inc. (80 W. Easy St., Simi Valley, CA 93065: 805/ 583-0808). This system uses a set of four injector nozzles that fire sequentially, at up to 65 psi, directly into intake runners that are part of a manifold specially fabricated by Kizer as a component of the Mr. Turbo system. The computer that operates the system, located under the ZX’s fuel tank, receives input from just two sources—a sensor that tells it which cylinder is firing, and one that measures manifold pressure. The setup is unlike some fuel-injection systems in that the individual squirts of fuel are not timed to coincide with the opening of intake valves. Martronic system designer Rick Marsh said testing with pulses timed to valve openings showed no horsepower gain. So he opted for the simpler, non-valve-timed system. That theme of simplicity is carried through by the turbocharger system. w hich brings w'ith it the potential, according to Kizer. of up to 280 horsepower.

The system is based on a RayJay Model F-40 turbo unit, spinning at up to 100.000 rpm. The turbocharger and wastegate both are located in front of the engine, rather than behind the cylinder block. This location, with the turbo impeller/compressor closer to the engine's exhaust ports, results in a bit less turbo lag. positions the weight of the turbo unit, wastegate and associated plumbing low on the bike, and keeps the heat soaked up by the turbocharger away from the rider and fuel system.

A by-product of turbocharging, which shoves an alreadycompressed fuel-air charge into each cylinder, is vastly increased overall compression—on this bike, at maximum boost, up to 20:1, Kizer says. With increased compression comes detonation, and to eliminate this, Mr. Mellow was equipped with a system that injects a 50/50 mixture of water and methanol into the intake manifold. This was a late addition. W'hen the bike came to Cycle World it came sans water injection. Within 80 miles of street riding, inaudible detonation had holed the number four piston. On went the water-injection system, with its neat reservoir doing double duty as a license-plate bracket. End of problem.

The bike came to us in prototype form; which is to say, a few details of its final specification had not yet been settled. One of those details concerned the fuel-supply curve built into the fuel-injection computer. This w;as slowT to let the bike settle back to idle after it had been ridden hard, and w as incapable of supplying a sufficiently rich mixture to permit cold starts without help from an auxiliary electronic choke. Additionally, the turbo system works so well with the fuel-injection system, Kizer says, that the wastegate his company has used for years is no longer capable of modulating manifold pressures down to the 12-to-15pound levels he had intended. Rather, he says, it is possible to see up to 30 pounds of boost in top gear, and 18 pounds in third. Kizer's kit will include a large wastegate that will more effectively control manifold pressure.

The result of Kizer's work is a sleeper of a motorcycle that looks, except for its splendid paint scheme—done by Kizer’s Hired Gun custom paint shop in Houston —like a stocker, but runs like a turpentined cat. The cost of all this hyper power production? Price for the turbo and injectionsystem kit is $3995. You do the installation, which includes mounting the exhaust system, and spreading and remounting the bottom of the right-side fairing so that it clears the large-bore header pipe and the w'aste gate.

To sample the best these bikes had to offer, we started out with a street ride. What we learned, first of all, is that the Suzuki is just what it looks like, it wears a license plate, lights and turn indicators, but its character is pure racebike, diluted just enough for it to be manageable for street use. Its seat—a piece of foam glued to the rear bodywork—is very high, and its clip-ons are very low, making the riding position a racy, bum-up, under-the-paint crouch. It is just what the team manager ordered for, say. Formula USA, or for a maxed-out, Sunday-morning blitz of your favorite set of curves. But it is perhaps not the optimal setup for more casual use.

This is a bike with a purpose, and that purpose is reflected by the range of adjustment in its suspension systems. We have raved previously about the quality and feel of the Yosh/Kayaba fork. Both the identically valved development carbon-fiber and production aluminum fork sets enhanced our regard for this equipment. The aluminum fork, a $2450 item, is easy to adjust and can be set up to deliver nearly any sort of damping and preload the rider wants. Its resistance to flex gives, when coupled to the GSX-R's quick steering geometry, an immediacy to steering inputs that most street riders can only dream about.

The rear-suspension system, with its mega-adjustable Öhlins shock and Yosh linkage, was more problematic. The sensitivity of the system meant that there were a million ways to get it wrong, and only one way to get it truly right. Additionally, what was right for one rider was wrong for the next, allowing the bike to porpoise and wallow most alarmingly when it was flicked into a corner by a rider using someone else’s setup. Once the proper settings were found, however. Big Nasty worked like the race-bred thoroughbred it is.

Its rear suspension may have been a little finicky, but that marvelous engine was anything but. A quick manipulation of the choke, a stab at the starter button, and it came alive, quickly settling into a throaty. 1200-rpm idle, replete with the sounds of rattling throttle slides escaping from the unfiltered carb intakes. I he lesson of this engine was—say it with us, now—discretion. There are huge amounts of horsepower on tap any time the engine is turning faster than 3000 rpm. Once the taeh needle has seen that number, just twist the throttle, and Stull Happens. Mostly what happens is a huge hit of' torque that tries to rotate the motorcycle around its back axle. Never have wheelies come so easily on a streetbike. To use the bike's potential, the rider must keep his weight forward, stand on the high, rearward pegs, and transfer weight to the bars to try to keep the front end on the ground as he exits corners. Fun? You bet. A small crack of' the twistgrip causes Bi» Nastv to leap forward, devouring straights, its fearsom acceleration relentlessly building, building, building, all the way to its peak at the top end of' fifth gear.

Fortunately, the bike’s brakes are well integrated with the rest of the Yoshimura package, and are capable of doing their job. the cast-iron rotors providing wonderful initial bite and terrific feel. Still, riding this bike is a combination of gymnastics and concentration. After a few hours, one begins understanding why top riders are worth every cent their race teams and sponsors pay them to ride equipment like this.

The turbo ZX-1 1, on the other hand, countered the Yosh/Suzuki’s razor-sharpness with the breezy, laid-back nature of a stock motorcycle, displaying an urgent but manageable power surge up to about 7000 rpm, all coupled to the stock ZX’s rational seating position and sporting-plush suspension calibrations. But at 7000 rpm under full throttle, the game changed, and the bike developed the sort of acceleration more normally associated with the space shuttle—enough to levitate this big, heavy bike’s front wheel in monster third-gear power wheelies. Whoopie!

The range of this bike’s suspension adjustments was much more narrow than that of Big Nasty, and the ZX-1 1 is, by design and intent, far less oriented towards racetrack use than the Yosh GSX-R 1 340. The bike therefore had a much more mellow, comfortable nature, and that’s how its nickname, Mr. Mellow, came into being. Get the turbo ZX into a full-boost condition, however, and that mellowness took on a surprisingly sharp edge. The boosted Kawi is capable of gulping down straight sections of road faster than you'd believe. But you’d better believe, and you'd better be thinking every second you’re aboard this bike. The ZX’s stock underpinnings are nicely balanced to the bike’s stock performance—though truly spirited riding can overheat its brakes. But the chassis has to stretch just a bit to cope with the kind of performance available from the turbo-toting ZX engine. Which is to say, this machine, with its considerable size and weight, may not be the ideal canyon blaster. But if you’re a devotee of the Stop Light Grand Prix, Mr. Mellow is the right tool for the job.

Just looking at this pair, you’ve got to wonder about their performance potential. Riding them on the street converts that wondering into a burning question. To answer it, we hauled the bikes to Carlsbad Raceway, a sealevel track that requires none of the compensating factors required by tracks situated at higher altitudes.

With Cycle World Associate Editor Don Canet up, both bikes were easily into the 9-second bracket, the ZX turning 9.81 at 157.06 mph, and the GSX-R turning 9.93 at 15L26. What, we wondered, would the bikes do with drag-racing luminary Jay Gleason aboard? We called Jay, he came, he rode, he turned 9.55 at 1 57.34 on the ZX, and 9.52 at 1 55.1 7 aboard the Suzuki.

Gleason’s comments? “Expletive deleted! They’re just so fast, it’s unbelievable.” He found the short, tall Suzuki very difficult to launch, but said of it, “Once she settles down, you can lay the wheat to her, and she says, ‘Let’s go!”’ And of the turbo ZX-1 1, he said, “That thing barks, man, big-time. It’s bitchin’.”

How bitchin’, on a scale of 1 to 200 mph? To find out, we fitted the GSX-R with Daytona-rated racing slicks and the ZX with Z-rated Metzeler tires, booked time at a paved test site deep in the Mojave desert and put land-speed ace Don Vesco to work running the bikes past Cycle Worlds radar gun. Some fiddling, some tuning, some gear changes revealed that the bikes were remarkably equal. The ZX cranked off a pass of 188 mph, the Yosh Suzuki posted a run of 1 86 mph.

But there’s one that got away. Kizer told us the ZX was geared to travel at 206 mph at its redline. Vesco made such a pass, the bike’s tach right at its redline, the speedo needle pointing far. far past 200 mph-about where 230 would be if the ZX’s 200-mph speedo read that high—and the seat of Vesco’s very experienced pants telling him he’d cracked the 200-mph barrier. But our radar gun malfunctioned. Disappointment and consternation, both of which were greatly amplified when on the next do-or-die pass, the Kawasaki died, devouring its number three connecting rod in an ominous and expensive clatter. Vesco is sure he exceeded 200 on Mr. Mellow. So are we. But we possess no real evidence of that. C'est hi guerre.

So, which of these bikes is the winner? Easy: Both are winners. Both push the limits of the street-performance envelope, doing a formidably efficient job of converting fuel into velocity. And unless you travel with some extremely fast company, there seems little doubt that either would qualify as the fastest streetbike in your town.

Which one of them would we own, if we had the choice and the money? Oh, that's a cruel question. We'll take ’em both, thank you very much. Just don’t tell our insurance agents. Don't tell our wives, either. s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Norton Girl And Other Tragedies

November 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeNone Dare Call It Progress

November 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsReplacements

November 1991 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUpheavals

November 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupNew For '92: A Buell For Shy People

November 1991