The Same Guy

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

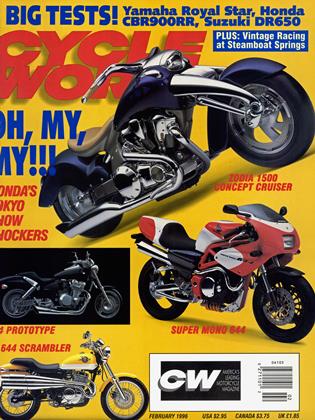

LAST MONTH I FLEW INTO SEDONA, ARIzona, for the introduction of Yamaha's new luxo-cruiser/tourer, the Royal Star.

Beautiful place, good ride, nice bike. Not precisely my kind of motorcycle, but a fine example of the type nevertheless. If Yamaha's marketing people are correct in their assessment of the motorcycle-buying public, I suspect the bike will do quite well.

We were given a flood of information on the Royal Star and its development, but there was one particular point that really caught my attention during the slide-and-pointer session that preceded the bike’s unveiling.

Yamaha’s marketing staff gave us a brief history of the ups and downs of the motorcycle biz from the 1950s onward: the growth of the motor culture in the late ’50s through the ’60s; the all-time sales peak of 1973, when an explosion of dirt-biking coincided with the popularity of exciting new streetbikes; a ’70s downturn in off-roading with public-land closures and the loss of two-strokes; a renewed peak of street riding (6 million active riders) in the late ’70s; a long slide downward through the ’80s as Baby Boomers had children and an increasing percentage of young people metamorphosed into passive video zombies who never go outdoors except to a mall.

Yamaha credits Harley-Davidson with arresting this big slide, catching the attention of those aging, moneyearning Boomers and giving them something they want to buy: cruisers. Low-key, highly styled motorcycles that suggest rebellion but are actually just fun to ride around on.

Not only has the downward slide been arrested, says Yamaha, but the Boomers are exhibiting a trend that apparently has never before been seen in the entire history of the whole world: They are becoming more active as they get older, rather than less.

Traditionally, 50-to-60-year-olds have slowed down, growing more comfortable and complacent, not to say doddering, buying cardigan sweaters, baggy pants with a scosh more room, etc.

But not the Boomers. No way.

We (I am one, after all) are apparently behaving like agitated air molecules in an overheated laboratory flask, bouncing off the walls. As a group we are getting fitter, spending more time outdoors and blowing more of our income on canoes, parachutes, mountain bikes, skis and motorcycles. For the time being, at least, it appears we are going to boogie ’til we drop.

Good for us, I say.

But obviously there’s also a dark side in all this.

Yamaha’s Ed Burke pointed out that all of the ups and downs of the motorcycle business, from the early ’60s to the present, have been caused by exactly the same bunch of people. He waved his pointer over a four-decade sales graph and said, “All the way through, this is the same guyT

Okay, not exactly the same guy. Naturally, some of us bought dirtbikes when others got Z-l Kawasakis, and others will buy Ducatis instead of Harleys or Royal Stars. But we are the same generation, with a similar slant on life and a shared notion of how it is well lived.

And, obviously, there are thousands of younger motorcyclists (some of them sitting in study hall right now) who are every bit as enthusiastic as we overstimulated aging Boomers-about whom they are no doubt sick to death of hearing.

Every generation has its special, curious breed who somehow escape television or computer screens to go outdoors and do something real.

What worries me, however, is there may not be enough of these inspired youthful types getting into motorcycling any more. And I’ve been won-

dering all week why that is.

Money?

Could be a big part of it. Bikes were cheap when I got into this sport. I paid off the loan on my first bike in one summer with two part-time jobs.

Can a 16-year-old buy any new bike now on one summer’s unskilled labor?

I doubt it.

On the other hand, my first bike was a Bridgestone Sport 50, so maybe my expectations were lower. You can probably buy a Honda Spree on one summer’s minimum wage, but I’m not sure these small scooters have the same social meaning my first motorcycle had. I suspect they are often just transportation rather than a foothold on a way of life.

There are, of course, lots of largerdisplacement used bikes out there at very low prices, but a used 600 is harder to slide past parental consent than a new Bridgestone 50, which I portrayed to my parents as a harmless little device-almost a bicycle-which it almost was. The 50 got them accustomed to the idea that I could ride and survive. The used Honda Super 90 and CB160 that came later were a much easier sell.

Maybe that’s what the motorcycle market needs: an inexpensive foot-inthe-door bike for 16-year-olds who have to do battle with their parents to have a bike at all.

The hard part, of course, is making a small bike that is not perceived as dorky. Whatever it is, it has to have substance and a certain cachet. It can’t pander.

That was the beauty of the smallbore bikes of the Sixties-they were not just aimed at kids. They were made for everyone, and everyone wanted themmovie stars, athletes, etc. They were a hot social commodity.

If I were Yamaha, I would take care of those bucks-up aging Boomers, to be sure, but I would also be scratching hard to come up with an inexpensive bike that a 16-year-old would be proud to own.

Not a diminutive baby chopper or a bad imitation of a much larger sportbike, but something desirable for itself, as so many small-bore bikes were in the Sixties. A bike to get this thing rolling again, to start another revolution.

We Same Guys are getting pretty old. We are all a lot closer to our last motorcycle than we are to our first. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue