Chain tension

LEANINGS

THERE ARE PROBABLY LOTS OF VARIAtions on this little domestic scene, but, generally speaking, here’s how it works: A man comes in from the garage wiping his hands on a rag and says to his wife, “You know, Honey, the chain is almost worn out on the motorcycle. I guess it’s time to put an ad in the paper and sell it to Peter Egan.” His wife nods sadly and says, “It was a good old bike, but I suppose if the chain is worn out, it has to go. What about the sprockets?”

“They’re pretty worn.”

“Yes, but are they really worn out? I mean, do the teeth have that sharp, spiky look, like the rowels on a pair of Spanish spurs—you know, the kind that are outlawed because they’re so cruel to the horse?”

“Well, they aren’t quite that worn out...”

“In that case, why don’t you ride the bike another 20,000 miles or so, and then we can sell it to Egan when the time is exactly right, just seconds before the whole driveline disintegrates.”

It may just be my paranoid imagination, but I can easily believe that conversations like this have actually taken place in homes all over America. It seems to have become axiomatic that no one will sell me a used motorcycle before its time, and its time, apparently, is that exact moment when the chain and sprockets are so worn out that another five or six revolutions of the rear wheel would spell certain disaster.

I’ve bought a lot of used bikes over the years, each with its own peculiar mechanical and cosmetic problems, but one thing they’ve all had in common was that their drive chains were shot. Not just stretched or a little loose, mind you, but fervently, dramatically worn out, as in dragging on the ground, caked in rust and giving off the kind of death-rattle that rollers and links make when they no longer wish to change direction at the countershaft sprocket.

This pattern started with my first used bike, the Honda S-90 I bought in 1966 (the one with the German Cross decals all over the tank and sidecovers). I bought it in a suburban neighborhood of Madison, Wisconsin, and was riding it back to my college dorm when I noticed it seemed a little low on power. On reaching the dorm parking lot, I put the Honda up on its centerstand and discovered that I could barely spin the rear wheel with two hands. This particular chain was overtightened and stiff as a board. When I removed the chain I discovered I could bend it into any shape I wanted, like a pipe cleaner, and hold it straight out in mid-air, or make it stand on end, in a mechanical variation on the Hindu rope trick. Miraculous stuif.

Being rather low on bucks, I never considered buying a new chain. I simply soaked the old one in a coifee can of oil all night, heated over the hotplate of my roommate’s popcorn maker. As the oil heated, gratifying waves of ancient brown oxide spread outward from the links, sending crud clouds into the clear, golden 50weight. Oil smoke rose from the coffee can, and all through the dorm that night, people dreamed they were trapped under the hood of a bigblock Chevy with serious blow-by. The chain worked fine when I put it back on the bike, though I was forced to invest heavily in a new master link, having winged the retaining clip into outer space with a screwdriver blade.

My track record didn’t improve much after that. My Honda CB160 came with a chain so rusty that it had a permanent kink which refused to flatten out, even going around the sprockets. This one also had to be boiled in oil.

About that time, my roommate Donnelly borrowed my brother-inlaw’s Honda 305 Dream so he could tour Canada with me. The Dream had one of those enclosed chains, shrouded to protect it from weather. What this full enclosure actually did was protect the chain from the vision and memory of the person who was supposed to oil it—specifically, my roommate—while trapping a certain amount of sand and gravel. We were somewhere south of Sault Ste. Marie in northern Michigan when smoke began pouring out of his chainguard and the bike ground to a halt.

My memory tells me the chain was glowing a dull cherry red in the dusk of early evening when we pulled the rubber plug and looked through the inspection hole. Is this possible, or just one of those Fellini-like cases of amplified recall? What I do remember with certainty is that I burned my fingers checking the chain tension. We took off the upper half of the cover, poured motor oil on the chain and rocked the bike until it was free to travel. Donnelly made it all the way home on this charred collection of links.

And then there was the Honda CB750 that my friend Howard warned me not to ride home from the house of the guy who sold it to me, lest the chain break and punch a hole in the cases and simultaneously lock up the rear wheel. And the Triumph Bonneville that had sat in a snowbank for three winters .... I could go on and on, but luckily for you, I’m running out of space.

The beat goes on. I traded up my old XL350 for a slightly newer ’82 XL500 a few months ago. The new bike is generally in beautiful shape, but of course, when I bought it you could swing a cat between the rollers and the sprocket teeth. The owners must have seen me coming.

I may be overstating the importance of worn-out drive in the reasoning process by which people decide to sell me their used bikes. Thinking about it now, there are clearly a couple of other important factors involved. Like the absolute baldness of the rear tire, the totally sulfated battery and the recent vanishing of both registration and title into thin air. Any one of these can trigger an immediate Sell order, followed by an almost Pavlovian tendency on my part to Buy.Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Racer's Hedge

September 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSunday Rider: No Apologies

September 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupCounter-Intuitive

September 1988 -

Roundup

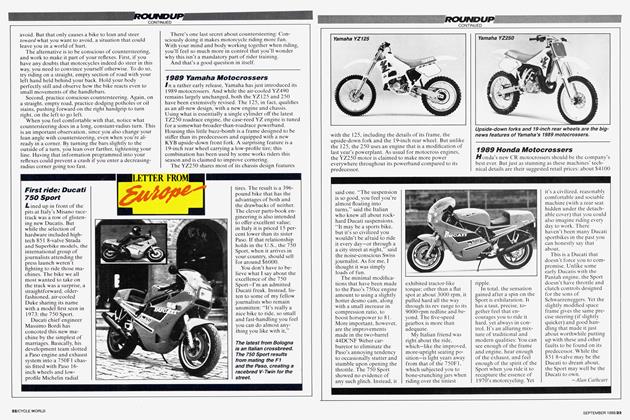

RoundupLetter From Europe

September 1988 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

September 1988 By Charles Everitt