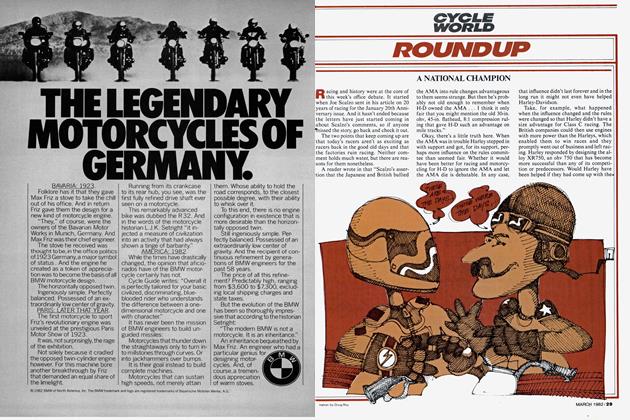

INVASION OF THE KILLER BEES

Two of Honda’s Smallest Hit the High Mileage Trail

Peter Egan

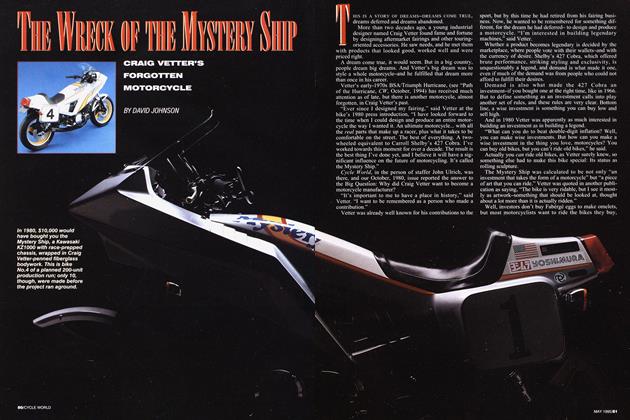

When Craig Vetter, designer of Windjammers, Mystery Ships, lightweight wheelchairs and his own mountaintop house, invited us northward to San Luis Obispo for a motorcycle fuel mileage contest everyone at the office immediately took stock of the gas-miserly bikes we had on hand. There were a couple of large staff-owned Ducatis that might do pretty well, provided they were tortured along at 45 mph in top gear, pinging and lugging and falling all over their 135mph gearing. Same for a big Guzzi we had around, but that treatment seemed cruel and out of character for the bikes.

Another possibility was a ’68 Triumph Daytona 500, legendary in its day for sipping gas but these days not much better than any of a whole raft of 400-550cc EPA-lean Twins and Fours ridden carefully. Besides, the carb ticklers, petcocks and float bowl gaskets on that particular bike lost more fuel through seepage and evaporation than the average Phantom jet uses on takeoff. The 500 was a sort of traveling petroleum wick. Scratch the Triumph.

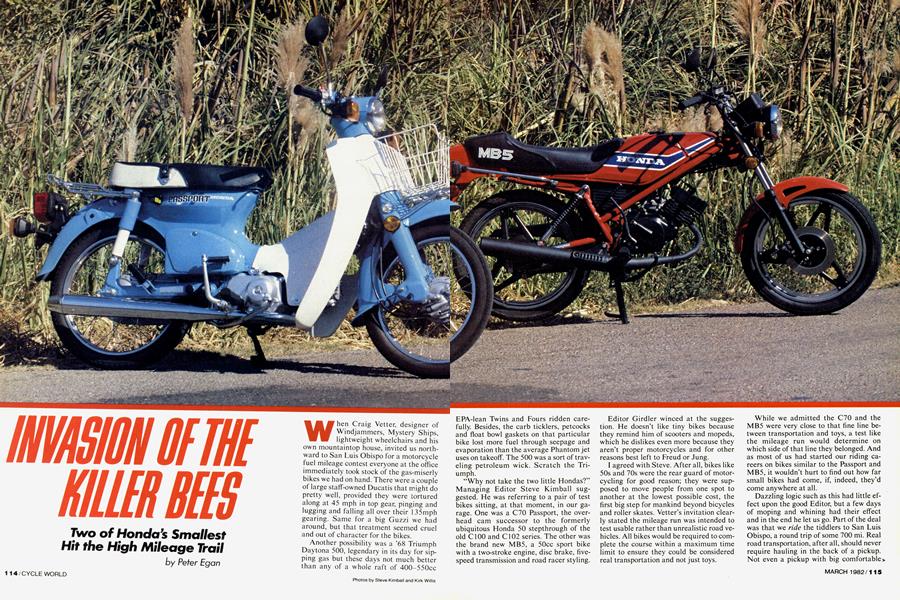

“Why not take the two little Hondas?“ Managing Editor Steve Kimball suggested. He was referring to a pair of test bikes sitting, at that moment, in our garage. One was a C70 Passport, the overhead cam successor to the formerly ubiquitous Honda 50 stepthrough of the old Cl00 and Cl02 series. The other was the brand new MB5, a 50cc sport bike with a two-stroke engine, disc brake, fivespeed transmission and road racer styling.

Editor Girdler winced at the suggestion. He doesn’t like tiny bikes because they remind him of scooters and mopeds, which he dislikes even more because they aren’t proper motorcycles and for other reasons best left to Freud or Jung.

I agreed with Steve. After all, bikes like 50s and 70s were the rear guard of motorcycling for good reason; they were supposed to move people from one spot to another at the lowest possible cost, the first big step for mankind beyond bicycles and roller skates. Vetter’s invitation clearly stated the mileage run was intended to test usable rather than unrealistic road vehicles. All bikes would be required to complete the course within a maximum time limit to ensure they could be considered real transportation and not just toys.

While we admitted the C70 and the MB5 were very close to that fine line between transportation and toys, a test like the mileage run would determine on which side of that line they belonged. And as most of us had started our riding careers on bikes similar to the Passport and MB5, it wouldn’t hurt to find out how far small bikes had come, if, indeed, they’d come anywhere at all.

Dazzling logic such as this had little effect upon the good Editor, but a few days of moping and whining had their effect and in the end he let us go. Part of the deal was that we ride the tiddlers to San Luis Obispo, a round trip of some 700 mi. Real road transportation, after all, should never require hauling in the back of a pickup. Not even a pickup with big comfortable> seats, a heater and a tape deck on a cold autumn weekend when the entire coast of California is locked in bone-chilling fog.

So ride it was, despite California’s 175cc minimum displacement for freeway travel, which meant we’d have to jog and twist our way northward avoiding main routes of travel like fugitives in the Underground Railroad.

Luckily, circuitous routes are no problem for S. Kimball, who claims to have lived in virtually every one-horse town in California during his rambling newspaperman days. He carries in his brain a printed circuit board of every known paved and unpaved state road (no doubt taking up good space most people use for other information) and can tell you on a moment’s reflection whether Highway 58 crosses Highway 43 north or south of Button willow and Shafter. Idiot savant, I believe, is the term used in clinical psychology.

We left on a Friday morning.

If you’ve never driven through L.A. from the southern tip to the northern edge, the city is roughly the size of Czechoslovakia, but with more car lots and taco joints than are found behind the Iron Curtain. Roads without entrance ramps and green signs are called “surface streets,” imparting an ethereal presence to the freeways, which are presumably not of this earth. Banished from the freeways, we traversed L.A. by surface street, one stoplight at a time, passing by many excellent opportunities to have our transmissions repaired while we waited, or to purchase color tile and custom carpet (three rooms, only $ 189.95). We rowed the gearshift levers for several hours and finally broke out of the metropolis at Malibu and followed the Coast Highway north.

The Passport and the M85 made a wonderful contrast going down the road. The Passport, done up in a two-tone paint scheme of white and a shade of turquoise stolen from a Melmac dinner plate in 1962, has sort of a jaunty, Singing Nun Takes a Vacation look about it, while the MB5 appears to be the kind of machine on which Freddie Spencer would drag his knee at Brands Hatch. We thought of dressing appropriately to the bikes; the Passport rider wearing a Maynard G. Krebs goatee, sweatshirt and sandals and strapping a set of bongos to the front basket, while the MB5 rider could suit up in brightly colored racing leathers. Luckily the weather was too cold for this kind of foolishness, so we bundled up in all our Belstaff gear and went disguised as British trials riders bound for Scotland.

Mechanically and functionally, both bikes work in a manner consistent with appearances. The Passport is ari old design but a good and reliable one. In many socalled Third World nations and anywhere else money and gasoline are in short supply, the Honda stepthrough in its various forms is the most common form of personal transportation. There are millions of these machines scattered throughout the tropical zones of the world. As “the bike that started it all,” the stepthrough first came to the U.S. with a 50cc pushrod engine with cast iron barrel and cylinder head and a three-speed transmission with an automatic clutch. The clutch was, and still is, disengaged by upward or downward pressure on the footshift lever, making clutch lever work and hand coordination unnecessary for riding. The clutch also works centrifugally, so the bike can be coasted to a stop in any gear without killing, downshifted to first (it will also take off in second) and left there until you are ready to go. Give it some revs, the clutch engages and you are on your way.

The old 50s had a one-down-two-up gearbox with a giant ratio gap, as well as a mandatory click through neutral, between first and second gears. This required a howling surge of revs in first just to keep the bike rolling on momentum until you could find second and pick up the pace again.

Honda dropped the stepthrough 50 from their lineup in 1970. America’s motorcycle interests had turned upstream.

Good designs don’t die easily, however, and the resurgence of interest in mopeds may have led Honda to reintroduce the small stepthrough. After all, they had a perfectly good version already in production for the rest of the world market, more sophisticated, more usable and no doubt longer lasting than most mopeds, and they could import it at a competitive price, tooling costs having been amortized about the time most of us were watching Leave it to Beaver. Granted, the Passport is not a moped; it must be licensed for the street like any other motorcycle. But for buyers with driver’s licenses already in hand and a willingness to pay for a set of plates, the Passport’s three-speed transmission and extra speed give it a big edge over mopeds for the errand-running set. (The Bentley always seems like wretched excess when all you need is a loaf of French bread.)

The Passport is changed from the old Cl00, and its electric-start sidekick the Cl02, in several ways. The engine is now a 70 and uses an aluminum head with a chain driven single overhead cam, a design very similar to that of the old Super 90 or S-65. Honda claimed 4.5 hp for the old 50 and makes no claims for the current 70, but horsepower is up considerably (maybe to, say, 6.5) as witnessed by the Passport’s ability to climb almost any hill in second gear. The 50 needed first. The transmission is also changed for the better; neutral is at the bottom and all three gears are up, eliminating the need to coast .in neutral between first and second as in days of old.

Front suspension is still by pivoting axle, swung forward from the bottoms of the stamped steel fork legs. The rear frame, in fact, is a stamped steel monocoque structure and the only pieces of tubing on the bike are the handlebars, hidden by another piece of stamped steel, and a large tube between the steering head and swing arm. The gas tank is a roughly triangular vessel under the seat. The gas cap is reached by lifting the seat, which hinges forward and has a clasp at the rear. Rear suspension is a conventional swing arm with two shocks and the drive chain is fully enclosed. Brakes are single leading shoe drums, front and rear. The front fender and the leg-fairing chaps are of plastic. The Passport comes from the factory with a luggage rack and front basket, both handy for errands. The front basket, we discovered the eve of an office party, holds six liters of cheap, nearly undrinkable champagne with no trouble at all, though the added weight in front of the fork tends to exaggerate steering input. But then so does drinking the six bottles of champagne.

The MB5 is an all-new addition to the Honda line, offering many features normally found only on larger, more expensive sport bikes. It has a 50cc piston-port two-stroke engine with a 10,500 rpm redline and a gear driven counterbalancer to reduce engine vibration. It has automatic oil injection from a tank hidden under a cover that appears to be the front of the gas tank, as well as breakerless CD I ignition. Other features not usually lavished on 50s are complete instrumentation, hydraulic front disc brake, ComStar wheels and a full tubular steel frame done in an X configuration. The engine, particu-

larly the cylinder head, has huge cooling fins on it, the kind more commonly found on competition dirt machines. Unlike the swing-axle Passport, it also has real hydraulic telescopic front forks, with 4.9 in. of travel. The gas tank holds 2.4 gal., compared with the Passport’s 1.1 gal. Honda’s literature lists the MB5 as weighing 8 lb. less than the Passport dry, but the extra oil and fuel in the MB5 even the score. Our scales had the MB5 at 198 lb. with half a tank of gas and the Passport tipping 190 lb. Suffice it to say that neither bike demands brutal strength to muscle around the garage. After climbing off a GS1100 with a fairing you feel like you’re handling a cardboard cutout of a motorcycle.

The 10,500 rpm redline is a clue to the MB5’s power curve; 39mm pistons don’t make horsepower by loafing around, they have to get up and move. In the MB5’s case that movement makes itself known as something resembling forward thrust at around 8000 rpm and pushes out a nice little burst of power right up to redline. Getting off the line with any alacrity demands a big handful of revs and a coordinated slippage of the clutch. Once the bike is under way the five-speed close-ratio transmission allows you to keep the engine riled up and churning it out. You can cruise along easily below 8000 rpm, however, as long as no sudden acceleration is called for.

The Passport’s 72cc engine also turns a lot of revs, though its four-stroke engine gives the impression of a lower level of activity, firing, as it does, half as often. The

Passport does not really have a power curve, as such; it has a giant flat spot that moves the bike down the road, getting the job done without noticeable surging or redistribution of g-forces acting on the rider’s body. In short, the MB5 feels jaunty and racy and the Passport feels subdued and calm. The only disruptive force acting on the Passport’s personality is the threespeed transmission and its automatic clutch. If shifted clumsily without proper regard for technique, it can set the bike bucking and rearing and make the rider feel like the Eastern dude who gets saddled with the wildest horse on the ranch. The very soft front suspension amplifies those movements. The MB5, on the other hand, has a clutch and transmission that work about as smoothly and precisely as any in motorcycling.

As soon as we hit the road it was clear that the MB5 could outperform the Passport in acceleration and speed despite its 23cc deficit. A later trip to the drag strip pinned down the figures for comparison. The Passport ran through the clocks (well, not ran, exactly) in 26.77 sec. at 46.6 mph in the quarter mile, while the MB5 smoked, literally, through in 22.68 sec. at 50.9 mph. The half mile run past the radar gun netted 49 mph for the Passport and 53 mph for the MB5. In braking tests, the drum-braked Passport stopped from 30 mph in 44 ft. and the disc-braked MB5 stopped in 41 ft. Neither distance is exceptional, compared with most larger bikes which normally stop somewhere between 25 and 35 ft. from that speed. Tiny tires were the limiting factor.

On the highway the MB5 was faster and less affected by headwinds whether traveling uphill, downhill or on the level. In one or two spots on the trek we were forced to use the freeway to cross bridges, that or be forced into long, arduous detours. As the freeway was forbidden territory, it was important to get these dashes over with quickly, so whoever was on the Passport would tuck in behind the 50 for a draft, making speeds over 50 mph possible for both bikes and reducing our exposure to the CHP. When the bridge was crossed, we’d head down to the nearest frontage road.

During one of these many searches for an alternate bridge, we blundered into the parking lot of a defunct nightclub in north Oxnard. The club was a gigantic building done in the style of a Polynesian lodge; steep grass roof, bamboo rafters, shields and crossed spears, etc. The old sign in front of the club had been torn out and a new one erected in its place. The lettering was done in rope letters, like an uncoiled lariat, and it said THE HAWAIIAN COWBOY. There was another sign, nailed diagonally across the front door. It said CLOSED in big red letters, like a USDA stamp of disapproval slapped against the entrance.

Steve swept his hand toward the building and said, “There it is. A standing refutation to H.L. Mencken’s overused observation that no one ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public. Somebody finally found the magic combination and proved it could be done.”

“The people who invented Muzak are probably trembling in their shoes,” I noted. Being Hawaiian and being a cowboy both had a certain appeal, but usually not on the same evening.

We had a late lunch in the small town of Arroyo Grande at one of Steve’s favorite old hangouts, the Tamale House, a nice little cafe where the cook has no secrets from the customers because the whole place is no larger than a walk-in closet. We had a good Mexican lunch and then followed a series of mysterious back roads known only to Steve until we got to San Luis Obispo just after dark. The 300 mi. trip took about nine hours, with stops.

We checked over our mileage figures at dinner that evening, trying not to muddy our calculations with spilled zinfandel and globs of cheese fondue, and discovered the MB5 had averaged 81 mpg on the trip while the Passport had done 102 mpg. This was under the worst of conditions, throttles twisted right to the stops, absolutely wide open for an entire day with the added factor of a late afternoon headwind. We hoped easier treatment in the mileage run would lower the rate of consumption.

On a crisp and autumnal Sunday morning we registered for the mileage contest on the village green in nearby Templeton, lining up with a couple hundred other motorcyclists, mostly in touring club colors for a Central Coast Motorcycle Assn, poker run which was slated to use the same route as the mileage contest. We reported to the official starting point, an Arco station just out of town. The station was like a racing paddock, full of strange vehicles being assembled and tuned. There were a diesel powered threewheeled streamliner (sounds like a Tom Wolfe title), a collection of diminutive two-stroke motorized bikes complete with 10-speed style dérailleurs and fairings, the Vetter streamliner, a heavily faired two wheeler with a semi-reclining cutout for the rider, powered by a 250cc Kawasaki four-stroke, a Honda factory-sponsored streamliner with cutouts in the cigarshaped body so the rider could stick his feet out like landing probes on a lunar capsule, and a number of random, rejetted, clip-on equipped midsize street bikes.

We filled our tanks at the pump, had them sealed with several dabs of a special tamper-proof glue, our odometer mileage recorded, and headed out on the course. Steve rode the Passport and I took the MB5. We knew from our trip up the coast that in flat-out riding the Passport got substantially better mileage than the MB5, and it was Steve’s reward for enduring the lower power of the Passport for most of the trip that he should have a better shot at the mileage record.

The course was beautifully laid out, a 64 mi. loop that followed twisty ridge and valley roads down toward the coast, swung northward along the Pacific Coast Highway and then climbed and curved back to Templeton on Santa Rosa Creek Rd. The key time for completing the course was 1 hour and 40 minutes, with 10 min. latitude on both sides, so we knew we’d have to make good time in the downhill sections to finish within the limit, as we couldn’t go 55 on the Coast Highway or blow anyone into the weeds on our labored climb back up the valley from the coast.

We were given a map and instructions before leaving, and the course was marked with stripes to indicate right or left turns. Steve, intimately familiar with the area, scanned the map and committed it to memory. So as we would come flying downhill toward an intersection and everyone else, including me, would slow down to check the map and the route markings, Steve would lean over and breeze through the corner holding a steady 45 or 50 mph and I would struggle to catch up and gradually repass. Drafting was forbidden, so our only exchanges of slipstream were during these passing maneuvers. Riders on the poker run were taking a nice relaxed ride through the scenic countryside, so we had to do a lot of cut and thrust riding to get around them and maintain our pace through the downhill curves.

On flat and uphill sections we went easy on the throttle, but not obsessively so, figuring the various streamliners and project bikes would push their mileage far beyond anything we could produce with a pair of totally stock tiddlers.

Not so. The Vetter and Honda streamliners both had minor crashes on the course, the former disabled and the latter coming in late. (The course was not dangerous, but there were tricky sections of loose pea gravel on some of the tighter corners, so slides and low-speed spills were easy to come by, especially on vehicles with unfamiliar steering and balance char-> acteristics.) When we got back to the Arco station the judges carefully filled our tanks and announced that the MB5 had averaged 139 mpg and the Passport had achieved 198 mpg. The Passport’s mileage was considerably higher than we had estimated it would be, so we asked them to check their figures again, protesting ourselves, in effect. Our own estimates had the bike at about 135 mpg. No, they said, the 198 mpg was correct, and in any case no one else in the Industry Class had even come close, so Steve was the class winner.

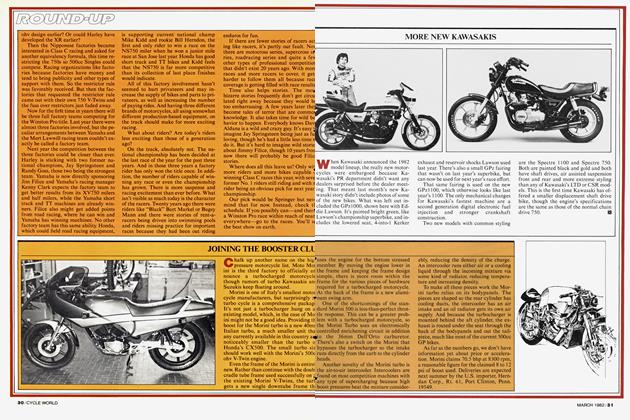

HONDA

C70 PASSPORT

HONDA

MB5

$798

He now has a nice trophy sitting in the office. It has a cleverly stylized fuel-efficient motorcycle sculpture sitting atop a model gas pump with a giant screw through the side of it. It is a perpetual trophy that will go to next year’s winner, unless Steve wins again. He has now tasted blood and is already plotting his return.

The trouble with riding a 50 and a 70 over 300 mi. from home is you have to ride them back, or spend the rest of your life in San Luis Obispo and give up your home and job. We considered these alternatives but, in the end, rode home.

The return trip reinforced some observations we’d made on the ride north. First, until you ride down the highway at 45 mph you never realize how many drivers in cars actually go slower than the top speed of the Passport and the MB5. We had imagined the bikes as traveling roadblocks, but were amazed to find ourselves actually passing dozens of cars on the open highway. Yes, there are people in Chevys with V-Eights who travel cross-country slower than a Honda 50! If that is true, who is to say the MB5 and the Passport are not real road transportation?

The problem here is that small bikes are really strung out on the highway and the V-Eight is barely running. In a motorcycling sense, all the slow and tedious aspects of traveling on a 50 or 70 virtually disappear when the displacement is bumped up to a mere 100 or 150cc. Motorcycles pay such a small penalty in weight and maneuverability with small displacement increases that it is simply not worth your while to assault the highway with a 50 when you could be riding a 100 or a 150 for just a little more money. Slightly bigger bikes travel at highway speeds with ease and have power to spare when climbing hills or avoiding errant automobiles. They are also generally more comfortable. The Passport and MB5 both have good seats for small bikes, but neither one is in any danger of driving the Easy-Boy Recliner Co. out of business. After nine hours in the saddle, we pulled into the Cycle World parking lot and dismounted. Steve barely had his helmet off before he said, “Next year I think we should try a pair of 175s,” and he barely finished speaking before I agreed with him.

The Passport and the MB5 are both town bikes, of course, never intended to be anything but easy, fun urban transportation at a low price (the suggested list on the MB5 is $798 and Honda doesn’t have a price on the ’82 Passport yet, though the ’81 s listed for $748; both are discounted at our neighborhood dealer for right around $700). And they are very good at what they do. The Passport is softly sprung, quiet, easy to operate and has useful carrying space with its luggage rack and basket. All those things, and the plastic leg guards, make it a nice civilized package for short trips. Women in dresses (and, one assumes, men in dresses) can straddle the bike with dignity.

The MB5 is a faster, more aggressive little machine, a raspy sport bike intended to be ridden more for entertainment than to take a six-pack of coke bottles back to the store. It has real suspension, a manual clutch, full instruments, and it handles much better than the slightly vague Passport. In fact it handles well by any standard. It is a fully modern machine, offering all the advances made in motorcycling over the last 20 years. Its two-stroke engine demands that oil he added to the injector reservoir occasionally, but this is a rare inconvenience as our bike used less than a quart of oil in 700 mi. of running nearly flat out, and it has a sight gauge at the front of the tank to warn you when oil is low. The MB5’s solo sporting character is pointed up by its smaller saddle and lack of passenger footpegs. Both machines were utterly reliable on the trip. We car. ried an extra spark plug along for the MB5, but didn’t need it.

The Good Editor was right. We came away from the mileage run feeling that the 50 and 70 were perhaps just a shade on the frivolous side of the transportation/toy dividing line, at least for long range travel. On the other hand, we rode them to the mileage rally and back home again, rather than assembling them out of the back of a pickup truck or sending chase vehicles after them as some of the competition was forced to do. No fairings, trick gearing, clip-ons or lean jetting, and they still got phenomenal mileage. As is so often the case, the boys at the factory have done their homework, and they’ve done it very well indeed.