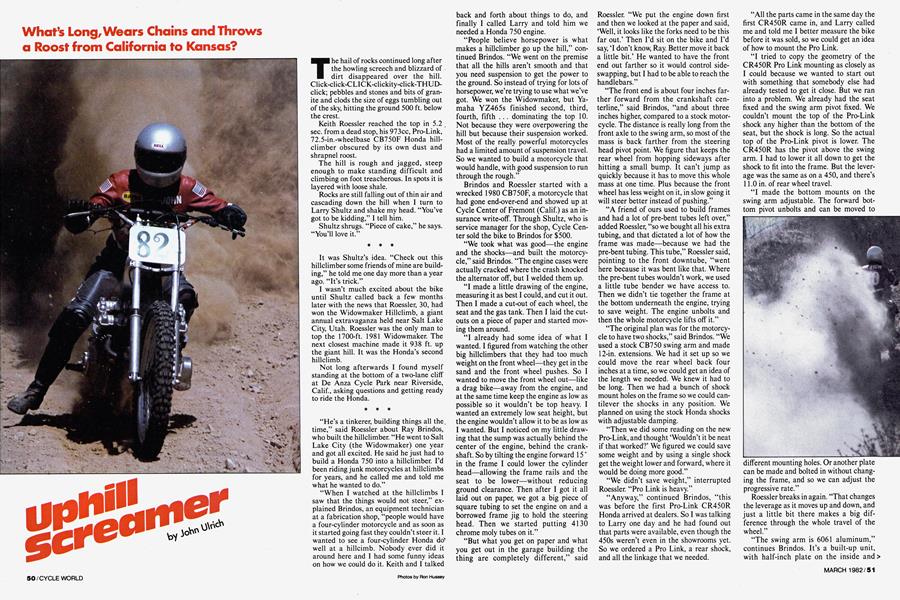

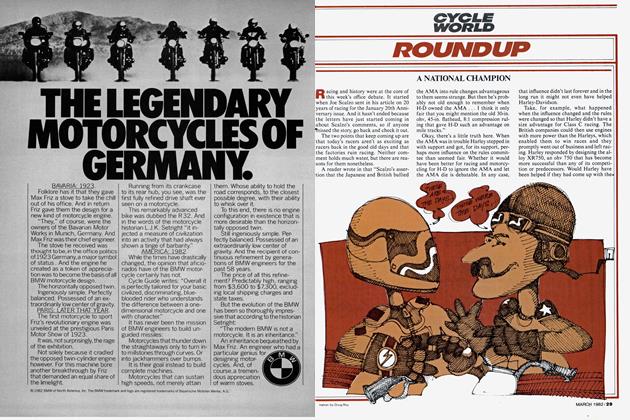

Uphill Screamer

John Ulrich

What’s Long, Wears Chains and Throws a Roost from California to Kansas?

The hail of rocks continued long after the howling screech and blizzard of dirt disappeared over the hill. Click-click-CLICK-clickity-click-THUDclick; pebbles and stones and bits of granite and clods the size of eggs tumbling out of the sky, hitting the ground 500 ft. below the crest.

Keith Roessler reached the top in 5.2 sec. from a dead stop, his 973cc, Pro-Link, 72.5-in.-wheelbase CB750F Honda hillclimber obscured by its own dust and shrapnel roost.

The hill is rough and jagged, steep enough to make standing difficult and climbing on foot treacherous. In spots it is layered with loose shale.

Rocks are still falling out of thin air and cascading down the hill when I turn to Larry Shultz and shake my head. “You’ve got to be kidding,” I tell him.

Shultz shrugs. “Piece of cake,” he says. “You’ll love it.”

It was Shultz’s idea. “Check out this hillclimber some friends of mine are building,” he told me one day more than a year ago. “It’s trick.”

I wasn’t much excited about the bike until Shultz called back a few months later with the news that Roessler, 30, had won the Widowmaker Hillclimb, a giant annual extravaganza held near Salt Lake City, Utah. Roessler was the only man to top the 1700-ft. 1981 Widowmaker. The next closest machine made it 938 ft. up the giant hill. It was the Honda’s second hillclimb.

Not long afterwards I found myself standing at the bottom of a two-lane cliff at De Anza Cycle Park near Riverside, Calif., asking questions and getting ready to ride the Honda.

“He’s a tinkerer, building things all the, time,” said Roessler about Ray Brindos, who built the hillclimber. “He went to Salt Lake City (the Widowmaker) one year and got all excited. He said he just had to build a Honda 750 into a hillclimber. I’d been riding junk motorcycles at hillclimbs for years, and he called me and told me what he wanted to do.”

“When I watched at the hillclimbs I saw that the things would not steer,” explained Brindos, an equipment technician at a fabrication shop, “people would have a four-cylinder motorcycle and as soon as it started going fast they couldn’t steer it. I wanted to see a four-cylinder Honda do’ well at a hillcimb. Nobody ever did it around here and I had some funny ideas on how we could do it. Keith and I talked back and forth about things to do, and finally I called Larry and told him we needed a Honda 750 engine.

“People believe horsepower is what makes a hillclimber go up the hill,” continued Brindos. “We went on the premise that all the hills aren’t smooth and that you need suspension to get the power to the ground. So instead of trying for lots of horsepower, we’re trying to use what we’ve got. We won the Widowmaker, but Yamaha YZ465s finished second, third, fourth, fifth ... dominating the top 10. Not because they were overpowering the hill but because their suspension worked. Most of the really powerful motorcycles had a limited amount of suspension travel. So we wanted to build a motorcycle that would handle, with good suspension to run through the rough.”

Brindos and Roessler started with a wrecked 1980 CB750F, a motorcycle that had gone end-over-end and showed up at Cycle Center of Fremont (Calif.) as an insurance write-off. Through Shultz, who is service manager for the shop, Cycle Center sold the bike to Brindos for $500.

“We took what was good—the engine and the shocks—and built the motorcycle,” said Brindos. “The engine cases were actually cracked where the crash knocked the alternator off, but I welded them up.

“I made a little drawing of the engine, measuring it as best I could, and cut it out. Then I made a cut-out of each wheel, the seat and the gas tank. Then I laid the cutouts on a piece of paper and started moving them around.

“I already had some idea of what I wanted. I figured from watching the other big hillclimbers that they had too much weight on the front wheel—they get in the sand and the front wheel pushes. So I wanted to move the front wheel out—like a drag bike—away from the engine, and at the same time keep the engine as low as possible so it wouldn’t be top heavy. I wanted an extremely low seat height, but the engine wouldn’t allow it to be as low as I wanted. But I noticed on my little drawing that the sump was actually behind the center of the engine, behind the crankshaft. So by tilting the engine forward 15 ° in the frame I could lower the cylinder head—allowing the frame rails and the seat to be lower—without reducing ground clearance. Then after I got it all laid out on paper, we got a big piece of square tubing to set the engine on and a borrowed frame jig to hold the steering head. Then we started putting 4130 chrome moly tubes on it.”

“But what you get on paper and what you get out in the garage building the thing are completely different,” said Roessler. “We put the engine down first and then we looked at the paper and said, ‘Well, it looks like the forks need to be this far out.’ Then I’d sit on the bike and I’d say, T don’t know, Ray. Better move it back a little bit.’ He wanted to have the front end out farther so it would control sideswapping, but I had to be able to reach the handlebars.”

“The front end is about four inches farther forward from the crankshaft centerline,” said Brindos, “and about three inches higher, compared to a stock motorcycle. The distance is really long from the front axle to the swing arm, so most of the mass is back farther from the steering head pivot point. We figure that keeps the rear wheel from hopping sideways after hitting a small bump. It can’t jump as quickly because it has to move this whole mass at one time. Plus because the front wheel has less weight on it, in slow going it will steer better instead of pushing.”

“A friend of ours used to build frames and had a lot of pre-bent tubes left over,” added Roessler, “so we bought all his extra tubing, and that dictated a lot of how the frame was made—because we had the pre-bent tubing. This tube,” Roessler said, pointing to the front downtube, “went here because it was bent like that. Where the pre-bent tubes wouldn’t work, we used a little tube bender we have access to. Then we didn’t tie together the frame at the bottom underneath the engine, trying to save weight. The engine unbolts and then the whole motorcycle lifts off it.”

“The original plan was for the motorcycle to have two shocks,” said Brindos. “We used a stock CB750 swing arm and made 12-in. extensions. We had it set up so we could move the rear wheel back four inches at a time, so we could get an idea of the length we needed. We knew it had to be long. Then we had a bunch of shock mount holes on the frame so we could cantilever the shocks in any position. We planned on using the stock Honda shocks with adjustable damping.

“Then we did some reading on the new Pro-Link, and thought ‘Wouldn’t it be neat if that worked?’ We figured we could save some weight and by using a single shock get the weight lower and forward, where it would be doing more good.”

“We didn’t save weight,” interrupted Roessler. “Pro Link is heavy.”

“Anyway,” continued Brindos, “this was before the first Pro-Link CR450R Honda arrived at dealers. So I was talking to Larry one day and he had found out that parts were available, even though the 450s weren’t even in the showrooms yet. So we ordered a Pro Link, a rear shock, and all the linkage that we needed.

“All the parts came in the same day the first CR450R came in, and Larry called me and told me I better measure the bike before it was sold, so we could get an idea of how to mount the Pro Link.

“I tried to copy the geometry of the CR450R Pro Link mounting as closely as I could because we wanted to start out with something that somebody else had already tested to get it close. But we ran into a problem. We already had the seat fixed and the swing arm pivot fixed. We couldn’t mount the top of the Pro-Link shock any higher than the bottom of the seat, but the shock is long. So the actual top of the Pro-Link pivot is lower. The CR450R has the pivot above the swing arm. I had to lower it all down to get the shock to fit into the frame. But the leverage was the same as on a 450, and there’s 11.0 in. of rear wheel travel.

“I made the bottom mounts on the swing arm adjustable. The forward bottom pivot unbolts and can be moved to

different mounting holes. Or another plate can be made and bolted in without changing the frame, and so we can adjust the progressive rate.”

Roessler breaks in again. “That changes the leverage as it moves up and down, and just a little bit there makes a big difference through the whole travel of the wheel.”

“The swing arm is 6061 aluminum,” continues Brindos. It’s a built-up unit, with half-inch plate on the inside and quarter-inch plate on top, tied together with 0.020-in. plate. It was welded and then heat-treated, so it’s 6061 now. If you weld something, it becomes kind of soft, so I had the arm heat-treated after it was welded. The swing arm itself weighs 12 lb. without the Pro Link linkage, and 21 lb. with the linkage. The bare frame weighs 21 lb.

“The inside of the swing arm has slots relieved into it, and extensions slide in from the back and bolt into place. We can put the rear wheel into 4.0-in. extensions or into 8.0-in. extensions. The wheelbase is 72.5 in. now, but we can extend that to 80 in. Or we can slide the axle forward in its slot and shorten the wheelbase to 68 in. We ran 80 in. at the Widowmaker. Next time we’ll run 84 in. at the Widowmaker.”

The bike has modified TT500 Yamaha front forks (with travel limited to increase slider engagement) and a 23-in. front wheel off an XR Honda. The rear rim is relatively narrow, a WM3-18 carrying a 4.85-18 Dunlop K81—the tread having been removed with a body grinder. The wheel uses a spool hub and no brake. Sheet metal screws retain the beads and air pressure varies from 20 to 70 psi.

“We don’t use a real wide rim because we believe that a wide rim tends to steer the motorcycle when you run over irregular ground,” said Brindos. “If you cross a rut or something a wide rim tends to change the direction of the motorcycle— it’s a lot more steerable and controllable with a narrower tire.”

The spokes in both wheels are small and spindly looking—the rear wheel spokes being from a stock early-model CB750 front wheel, cut down to fit. But Brindos and Roessler say that spoke size doesn’t seem to matter, that they haven’t had any problems with the spokes they use.

“Did you tell him our secret, why we beat everybody?” Roessler asked Brindos. Then, without waiting for an answer, Roessler continued. “The biggest problem people have is with the drive chain coming off, when brush gets into it. So we put a chain guide with a Yamaha 465 block mounted right where the rear sprocket is almost touching it, so the guide is constantly feeding the chain onto the sprocket teeth.”

Roessler is entitled to his opinion of the team’s winning secret. But to an outsider, the real secret seems to lie in the intricate devices attached to the rear tire to provide traction. The devices take two forms— steel paddles or elaborate chains. When the paddles are used, tire pressure is 70 psi, with the chains, 20 psi.

“On a fast hill, where all you’re concerned about is traction, the paddles get better traction. They hook up real good,” said Roessler. “But if you’ve got a hill that’s steep and rough, where you’re going to come to a ledge and have to shut it off and then turn it back on, you don’t want a lot of traction—you want the tire to break loose so the motor won’t bog. That’s when you’d use the chains, and that’s what we did at the Widowmaker.”

Brindos made the paddles. “Since this was our first attempt at making paddles, we didn’t have a real good idea on how tall to make them,” he explained. “If they’re too tall they hook up extremely well at slow speed, but we think as the speed increases, as the tire is spinning faster, that the taller paddles don’t hook as well. So we looked at paddles used by other people and picked a height that looked like a happy medium. They seem to work fine.

“I made them out of cold-rolled steel, the base Win. thick and the other pieces 16 gauge, ‘/ïó-in. thick. They’re just bandsawed out, wrapped together and welded. When they wear down some more I think I’ll weld hard-facing on them to keep the corners from rounding off—because the corners are starting to round off now.”

The chains are works of art in themselves, topped by angled pieces of steel that hook into the ground. “It’s common practice to use motorcycle (drive) chain for crosslinks, and they have what they call pilers,” said Brindos. “The pilers are pieces of chain attached at their ends to the cross chains, and they stand out on top of the motorcycle chain to give you more height when the wheel is spinning. Those chains are run loose so they can get to the ground in front of the tire contact patch when the wheel is spinning.

“We came up with the idea of using this method of scooping the dirt instead of the piler motorcycle chain that was used before,” Brindos continued. “We just happened to see this stuff at a scrap metal yard. They had a big roll of conveyor belt chain, and that’s where we got our crosslinks.”

“The conveyor belt tables were bolted to the paddle-shaped things on the chain,” added Roessler. “The cross pieces, the plates for the conveyor belt table, are parallel with the tire surface, and when they hit the ground they stand up about 1.5-in. and dig in to increase traction.”

“We had to weld-in gussets underneath each piece of conveyor belt table bracket,” said Brindos, “because the first time we ran the chains, every time it hooked a rock the brackets would break off—those pieces are hardened to the point where they just barely bend and then snap off. We lost about six of them at the first hillclimb. After we put the gussets on we haven’t lost any.”

“The other thing that’s unique about the chains is the use of side cables,” said Roessler, picking up the story. “Most people use regular side chain. To try to keep the weight down we tried cables. We had a little trouble with it but now have them pretty well figured out. For example, we fitted pivoting links where the cross chains meet the side cables, because before the cross chains would kink the side cables there and break them off.”

“Then we used little pieces of copper tubing around the cables where they go through the steel cross chain links,” added Brindos, “so the steel doesn’t fray the cable strands. The fittings joining the side cables are unique also. We found them at the scrap metal yard, hooked onto some cable. They have a special wedge in them, and the harder the cable is pulled the tighter the fitting gets. It actually pulls on all the strands at once and gets tighter. It pulls evenly, and doesn’t crimp the cables. We wish we knew where they came from because we only found two sets.”

“The thing about these chains,” said Roessler, “is that the tire can spin, but when the tire gets spinning faster the chains grow and stand up and then hook up better. They don’t hook up like the paddles, so you can get some wheelspin down low. At Salt Lake City that’s real important because you wanted to be able to be able to break the tire loose any time—if you got too much traction after you shut off" the throttle and turned it back on, the motor would lug.”

The first time the bike competed, the engine was internally stock. Brindos installed a set of 29mm Mikuni smoothbore carburetors breathing through a handmade aluminum airbox and a K&N air filter. He retained the stock rubber velocity stacks found in Honda airboxes and made the 4-into-2 exhaust system, which exits on the right side to simplify spark arrester installation (for practice runs in areas requiring spark arresters—when arresters are not used, the pipes are unmuffled).

Running the bike on pump gasoline, Roessler entered a local hillclimb and faced a nitro-burning lOOOcc Triumph in a showdown for first place. Roessler made it over the top—the only other machine over was the Triumph—but took 0.025 sec. longer to do so.

“We had to make it bigger,” said Brindos. The problem was lack of money. Ray Brindos’ brother, Stan, stepped in. “Stan said ‘I’m not going all the way to Salt Lake City to see you get second place,’ ” said Shultz, recounting the story, “so he bought the engine parts, and we put the name of his auto stereo store, Tapes Unlimited of San Jose, on the bike.”

The parts included an Ontario Moto Tech 67mm, 11:1 c.r., three-ring piston kit, and CB900F crankshaft, connecting rods, primary chain, upper primary chain tensioner slipper, cylinder studs, camshafts and cam chains. The modifications brought displacement up to 973cc. The engine was assembled with Shultz’s help and was taken to the dragstrip with a street tire installed. It turned 10.82 sec. with a terminal speed of 123 mph.

The modifications had clearly increased the horsepower, but more important, delivered the extra power across a wide rpm range.

“It works good,” said Roessler. “Like at Salt Lake City, you have to drive the motorcycle up and around the bushes, and over things. A couple of times I came up on a bush and I didn’t think I could keep going. But I just turned the motorcycle, went around the bush, and got my speed back up. I can actually drive it like a trials motor up there, of course you’re going quite a bit faster. On a rough hill I’m always driving it, like never getting over 6000-7000 rpm.” The bike is equipped with a tachometer, and I asked why. “When you’re going up the hill you’re paying attention to other things so you can’t look at the tach,” answered Roessler. “The problem is that the engine is so smooth that you can’t really feel what rpm it’s pulling and the exhaust sounds about the same all the time. We have the tach so in practice we can get an idea of where the gearing needs to be.” “It always sounds like it’s really turning, like it’s really working good,” added Brindos. “But it might not feel just right. So you can look at the tach and see that it’s only turning 5000 rpm. Then you know it’s got a problem. If it lifts the rear wheel and the valves start to float you can hear it start spitting in the exhaust pipes. Other than that it sounds the same the whole time.”

Gearing depends upon the type of hill.

“The first thing you do in practice is find a hill that’s close to the one you’ll actually have to climb, because they won’t let you practice on the actual hill,” continued Roessler. “On a smooth hill you want the motorcycle to go as fast as it will go and still spin the rear tire when you take off, without bogging.”

“If it’s geared close to right,” said Brin> dos, “when the bike gets to the top of the hill it’s close to floating the valves. You get most of your drive right off the start and can almost freewind the engine at the end.”

“That’s on a smooth hill,” Roessler said. “On a rough hill you look at what you’ve got to go around and you kind of know how fast you want to go. You want the engine to turn down in the mid-range, so you can work it up the hill, on and off the throttle. Then when you get to a spot where you can go fast, you’ve got some left over.

“You don’t want the front wheel off the ground,” Roessler continued. “You want it just touching the ground, skimming along. You can adjust that in setting up the bike by moving the forks up or down in the triple clamps or moving the rear wheel forward or backward. Moving the rear wheel back about half an inch makes the same difference as lowering the front end about a quarter inch. In both cases the rear wheel has less leverage on the front of the motorcycle so it has a harder time lifting it up.^

“Available traction makes a big difference,” Roessler said. “If you get a lot of traction, you make the bike longer so it won’t lift up the front wheel. If you can’t get enough traction you just keep making the wheelbase shorter until it starts working.

“Then, on gearing, we want to be able to run just one gear—usually second gear— all the way up the hill, coming out of the hole hard. And on a smooth hill you want it to go fast. Changing just one tooth on the rear sprocket makes a big difference.

“On a smooth hill the throttle’s wide open all the time, with the front end just touching the ground. But as soon as it starts to come up I crack the throttle off and then on again real quick before the front end even rises an inch or two. In the old days they used to hit a kill button when the front wheel started to come up, but those engines didn’t respond like this one. You shut the throttle off and back on and it’s made a difference with this motorcycle.”

“This is a smooth hill,” Roesler tells me as I look from the bike to the jagged face rising in front of me.

He rolls the bike into position, backing the rear wheel up until it almost touches a plywood barrier built to protect bystanders from thrown dirt and rocks.

This particular hill is used for uphill drag races, two bikes starting in parallel lanes, the first one over the top winning.

Brindos carries a remote battery pack over to the bike, and plugs it into terminals attached to the stock electric starter. The bike carries a small battery to feed the stock ignition, run total loss. Retaining the starter motor makes the bike easy to fire up, and using the remote battery for the starter reduces weight.

The bike starts and idles, then howls briefly as Roessler, (wearing jeans, leather jacket and open face helmet), brings up the rpm. He nails the throttle and releases the clutch at the same instant, the engine’s scream rattling through the valley as the bike rockets forward and up, riding a plume of dust and rock.

Then he’s over the top, the sound echoing still. Finally the engine noise is gone, Roessler’s trip memorialized only by the hard rock rain.

Roessler rides the hillclimber down a trail behind the hill and returns. It’s time for me to make a run. The paddles on the rear wheel have dug a trench in the starting area, and after I back the bike into position, Shultz and Roessler shovel dirt to fill in the trench.

“The dirt gives you a cushion to spin on,” Roessler says.

“Get as straight as you can,” Shultz tells me. “If you’re leaned one way or the other the bike takes off sideways, and you fall on your head. Then you’re in big trouble.”

Brindos plugs in the starter leads and loops the deadman switch around my wrist—if I fall off, the lead will pull out a plug and disconnect the ignition.

“Keep the gas on over that bump because if you don’t it will spit you over the bars,” Roessler says, po; inting at a lump three-quarters of the w; ay up the sheer wall. “It’s nerve wrackin g going fast and not shutting the throttle c >ff at a big bump, but you can’t do it any ot her way.”

Brindos throws the sv /itch on the battery pack and the starter spins the engine, which fires instantly. I b lip the throttle a few times, stare long and 1 hard at the hill, and put the bike in secón d gear.

The tach is only at 350 0 when I let go of the clutch and grab a I îandful, but I’ve never seen any engine ¿ go from 3500 to 9500 rpm so quickly—an id then I’m at the hill, no time for the tach , the final sloped approach reaching adot >e wall, vertical, unclimbable.

Climbable.

Because with no trout »Íe, no hesitation, no twitch the bike rolls u pward, controllable, that bizarre shriek o: f an exhaust note cascading rearward and r îothing ahead except brown hill and gra; y shale and blue sky, the bike calmly pic king its way upward, around this lump, t hat hole, over the bump. Nothing to indica te the violence of the barrage sent out behii id, from the spinning, churning rear whet Û, nothing to tell the rider that this hill is b eatable only by a fly.

And I’m over.

The ride back is strai ige, the paddles going clump-clump-clui np on the hard dirt road, the needle bl: azing across the tach face with each blip < af the throttle.

Roessler and Brindos s^ vitch paddles for chains, saying the chains will throw a better roost for the photos, and then I’m on the line again.

“You weren’t going ver y fast,” Roessler tells me. “Pretend that i Cenny Roberts is next to you and you’re gc mna race him to the first hill.”

Which I do, topping th e hill again, easily, faster, but not as quic kly as Roessler’s 5.2 sec. record on this clir nb with this bike.

Halfway up it occurs t< a me that the hill doesn’t even look like a hi 11 when you’re on it, just the way a mean sei t of ess-curves on a roadrace course straigh ten out from the view of the racer. On the gas, off the gas, on the gas again. The moi tor responds perfectly, punches forward w ithout lifting the front wheel, just makinig that hill slide down, behind.

At the top, riding bac:k on the return road, slowly, the chains th row dirt over my helmet and it drops in fro nt of me, bouncing off the gas tank and ft mder.

“The neat thing about this bike,” Roessler tells me when I return , “is that you get to the bottom of a hill that you just know is so steep that there’s no w ay anything can climb it, and then the bik e just goes right up.”

“Yeah,” I tell him. “Hi llclimbing looks bad, terrible, awful when you watch it, like the hardest, most d angerous thing anybody could do. But wi th this bike . . . it’s easy.”