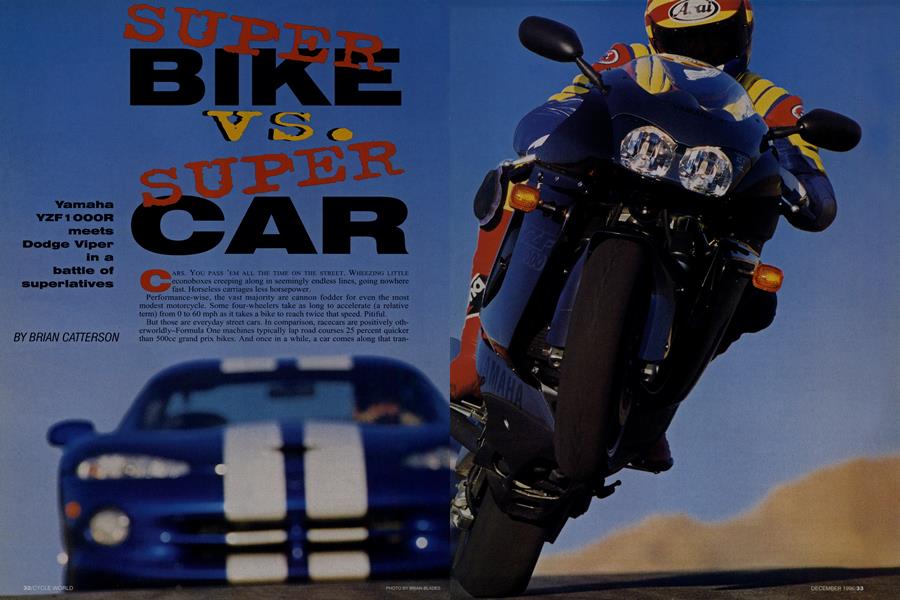

SUPER BIKE vs. SUPER CAR

Yamaha YZF1000R meets Dodge Viper in a battle of superlatives

BRIAN CATTERSON

CARS. You PASS 'EM ALL THE TIME ON THE STREET. WHEEZING LITTLE econoboxes creeping along in seemingly endless lines, going nowhere fast. Horseless carriages less horsepower.

Performance-wise, the vast majority are cannon fodder for even the most modest motorcycle. Some four-wheelers take as long to accelerate (a relative term) from 0 to 60 mph as it takes a bike to reach twice that speed. Pitiful. But those are everyday street cars. In comparison, racecars are positively otherworldly—Formula One machines typically lap road courses 25 percent quicker than 500cc grand prix bikes. And once in a while, a car comes along that transcends those boundaries. A car like the Dodge Viper GTS coupe. A 450-horsepower racecar-for-the-street whose specifications sheet includes a fuel-injected V-10 engine, a six-speed transmission, mammoth, 13-inch-wide rear tires and a whopping, $73,000 price tag. In other words, a supercar.

con

The Viper GTS’s performance potential was not lost on the editors at Cycle World's sister publication, Car and Driver. So, when their Editor-in-Chief Csaba Csere (pronounced “Chubbah Cheddah,” not unlike the guy who did the Twist) called the CW offices to ask if we’d like to collaborate on a car versus bike story, he wasn’t just looking for something to fill his pages-he was looking to settle the score. More than that, he was looking to vindicate his belief, expressed in an editorial he’d written three years before, that, and I quote, “...a motorcycle can’t keep up with a car on an unforgiving mountain road.”

We here at CW didn’t exactly agree with Csaba’s opinion. Car versus bike? Sure thing, bring on that door-slammer. We took the bait quicker than you can holler, “Fish on!”

That was our first mistake. There would be others.

THE CONTENDERS

From the beginning, we knew which car we were up against. But which bike to send into the arena, that was the question. To help us decide, we studied the fields of battle: a timed section of twisty mountain road, timed laps of two different roadrace tracks, dragstrip runs, and a battery of! tests that would measure acceleration, braking, roadholding I and outright speed.

That last one presented a serious challenge. According to I the September, 1996, issue of Car and Driver, the Viper! GTS is capable of going 177 mph. Uh-huh, and they arrived at that figure by, what, copying it out of the sales brochure? ! No, actually, one of the editors arrived at that speed byj stepping on the pedal farthest to the right. And holding it to the floor for a long, long time.

Trouble is, that’s 1 mph faster than the fastest bike| we’ve ever tested, the original, 1990 Kawasaki ZX-11. And while Honda’s forthcoming CBR1100 Double-Xj Supermouthful promises to surpass that speed, we couldn’t get one in time. Besides which, there was no guarantee the Honda would actually go that fast (see

“King of Speed,” page 48), and its considerable heft and questionable linked braking system would likely compromise its chances on the racetrack.

No, better to concede the top-speed portion of our testing to the car and get something that stood a better chance on the track. Something like Yamaha’s YZF1000R. Available overseas since earlier this year as the Thunder Ace (“Distant Thunder,” CW, May, 1996), the YZF has received rave reviews for its potent, 135-horsepower inline fourcylinder engine, nimble handling and eyeball-popping brakes. No surprise, really, considering that it marries an uprated version of the proven FZR1000 engine with what is essentially a YZF750 chassis-a proven combination, judging by the numerous Formula USA and SuperTeams wins carded by similar homemade hybrids in recent years. Best of all, we already had one in the CW garage. A mongoose for their snake.

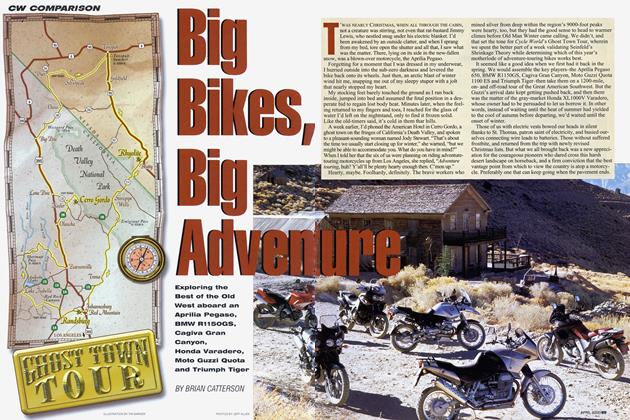

THE STREET

Early one weekday morning, we assembled at the ! Newcombs Ranch cafe on Southern California’s famed Angeles Crest Highway. To be honest, we would have preferred to use a tighter, lightly traveled, dead-end canyon road for the street portion of our testing, but because Csaba had mentioned the Crest in his earlier editorial, he was determined to use it.

Seeing as how this first contest was intended to gauge real-world performance, we came up with two rules: (1) ¡Neither vehicle would take any practice runs, and (2) we would stay to the right of the centerline at all times.

After carefully selecting a 6.3-mile stretch of road with no intersections and as few blind comers as possible, we sta¡ tioned personnel armed with stopwatches and walkie-talkies at the start and finish lines. The two vehicles would leave ! the start at a predetermined interval, and this would be com¡ pared to the interval at the finish to decide the winner.

Csaba and the Viper went first. The car appeared to get off to a slow start, but even before Senior Editor Jon Thompson waved me off one minute later, I could hear tires squealing in the distance.

Since we were starting from a standstill with cold rubber, I also eased into my mn-I’ve seen too many racers fall on I the warm-up lap to dive in head-first. Good thing, too, as I immediately discovered that a road crew had laid asphalt sealer since my last visit, rendering the first mile of the course quite slippery. Since I was reluctant to lean the bike very far on the goo, it took longer than normal for the tires to reach their optimum operating temperature.

How long? Well, photographer Rich Chenet was stationed 2.2 miles from the starting line, and he shot a photo sequence that clearly shows the YZF’s rear tire leaving a black stripe on the pavement. Much as I’d like to claim it, this wasn’t due to tire-spinning heroics-it was merely an indication that the rear Dunlop was still cold.

How could this be possible, this far into the run? Consider | that 2.2 miles is, coincidentally, the minimum required! length for a GP track. And if it takes racers one lap to warm-

up their tires, why should a streetbike be any different?

Cars, meanwhile, do not struggle with cold tires. Their greater weight means their tires heat up almost immediately; in fact, Csaba said that cars commonly record their best skidpad numbers on the first or second go-round.

Having raced both an FZRlOOO-powered GTS 1000 and a YZF750 Supersport bike last year, I immediately felt at home on the YZF1000. The revised motor displays immensely usable midrange power, with peak horsepower at 9500 rpm-2000 shy of redline. The quick-steering chassis allows rapid transitions, and yet the 56.3-inch wheelbase (.4-inch longer than the YZF750) makes it rock-steady inj fast sweepers. This gave me the confidence I needed to put my head down and ride much harder than I normally would on the street-not an all-out, traction-limited roadrace pace, but pretty dam close to it.

Thus, I was more than a little disappointed when finishline timers David Edwards and Matthew Miles informed me that Csaba had beaten my time by 12.4 seconds, an average speed differential of some 3 mph. After voicing my belief that cold tires had adversely affected my time, Car and Driver's Technical Editor Barry Winfield asked me if I’d like to repeat the run with warm tires. A bike guy at heart, Barry has worked for motorcycle magazines in England and his native South Africa, so he knew where I was coming from.

After taking a few moments to consider his offer, I declined. Twelve seconds is a pretty significant chunk of time, and while I almost certainly would have gone faster the I second time, there was no guarantee that Csaba (who in the interest of fairness would also get another run) wouldn’t I improve his time as well. Instead, I opted to take my lumps and try to settle the score at Willow Springs.

I’m glad I did. Because after driving the Viper through the Angeles National Forest on the way to our hotel in Palmdale, I developed a newfound respect for sports cars. The YZF’s 1003cc inline-Four produces an impressive 80 foot-pounds of torque at 8250 rpm, but the Viper’s massive 8-liter (7990cc) V-10 truck engine makes more than six times that much at a mere 3700 rpm.

Of course, with a displacement eight times the size of the YZF’s, the Viper’s engine ought to make a lot of power. But considering its size, it really doesn’t: It chums out just 56 horsepower per liter, compared to the YZF’s 135 bhp/liter.

Interestingly, both vehicles’ powerplants incorporate 20valves-they’re just arranged differently. The Viper’s ohv V-10 employs pushrods and rocker arms to open its two valves per cylinder, while the YZF’s dohc inline-Four relies on inverted buckets to open its five (three intake, two exhaust) valves per cylinder. By comparison, the Viper’s engine is much more primitive-though, like HarleyDavidson’s Evolution engines, it does have an aluminum block, as opposed to the cast-iron blocks of its forebears.

But as impressive as the Viper’s power output is, its roadholding ability is even more so. Remember the pavement sealer I spoke of earlier? It had no effect on the Viper at all. Pavement ripples, seams, sand and gravel? Ditto. You see a comer, you turn the steering wheel, the car goes around the comer-it’s as simple as that. The taut chassis dances over ripples like an oversized go-kart, but the four huge Michelins never threaten to come unstuck. It’s so easy to go fast that crashing seems like an impossibility.

“Hmmm,” I thought as I pulled into the hotel parking lot, “this thing could be trouble at Willow Springs.”

THE TRACK

After the incident on Angeles Crest, I was looking forward to the controlled environment of the racetrack. So I was more than a little miffed to discover that this would not be the case today. The Willow Springs road course was in the worst shape we’d ever seen it, with racecars having severely rippled the pavement in Turns 2, 3 and 5, and sand from an earth-moving project scattered across Turn 4. It looked like... well, like the Angeles Crest Highway. I wanted to leave right then and there, but the promise of hot laps on the tighter Streets of Willow circuit that afternoon gave me hope.

Csaba, meanwhile, found the Viper virtually unaffected by the track conditions, and quickly went about reacquainting himself with “The Fastest Road in the West.” Talking on the phone a few weeks prior to our test, he’d predicted the Viper would do 1:35s, and he was soon fulfilling his prophecy. I, on the other hand, had predicted 1:32s for the YZF, and was frustrated to find myself languishing in the 1:37 range, despite having fitted the bike with a fresh set of gummy Dunlop Sportmax II GP radiais.

After modifying my line through Turn 4 to keep the bike as ¡ upright as possible across the sand, I set about trying to make ! the chassis work over the bumps. It was not an easy task.

Motorcycle racers who have progressed to cars (see “Making the Switch,” page 42) talk about how important set-up is-if your car isn’t balanced, you’ll soon find yourself going backwards through the field. Conversely, a ¡motorcycle racer can often ride around his vehicle’s set!up problems.

Paradoxically, our experience with these two street vehi; des was just the opposite. The Viper has no provisions for I suspension adjustments, but it didn’t need any, either;

; Csaba raised the air pressure in the front tires to curb a ¡ slight “push,” and that was it. I, on the other hand, twiddled every suspension-adjustment knob at my disposal and still ¡couldn’t get the YZF handling to my liking-even with ladvice from Yamaha roadracing coordinator Tom Halverson and Superbike racer Tom Kipp, who were on I hand for a YZF600 advertising photo shoot.

The main culprits were too-soft fork and shock springs I for my weight. At a smidge over 6-feet tall and 200 ¡pounds, I admit that I’m larger than the average roadracer. But I’m by no means abnormally large-especially in terms of the average Open-class sportbike rider. Cranking the spring preload way up helped keep the muffler from ¡touching down in right-handers, but caused the fork to ‘pogo” over crested Turn 6, even with the rebound damping set at maximum.

Further complicating the proceedings was the fact that right about the time I decided the YZF was set-up as good as it was going to get, the infamous Willow wind kicked up, making 145-mph Turn 8 an even scarier place than usual.

I Would somebody please give me a break?!

Suddenly, somebody did-or so it seemed. On just its third ¡timed lap, while going down the back straight, the Viper blew a big puff of smoke out its exhausts. By the time we’d ¡finished hollering, “Did you see that?” it was over. The I Viper expired in a huge white cloud as it exited Turn 9, and ¡coasted to a stop at start/finish. The green engine coolant ¡dripping from its right-side exhaust pipes suggested a blown head gasket, but Csaba said it sounded far worse than that. A couple of hours later, the Viper was unceremoniously hauled away on a flatbed truck.

Csaba wasn’t too surprised by this sudden development. Though he claimed that he wasn’t hammering the car, and was keeping the revs well below the 6000-rpm redline, the temperature gauge had been climbing steadily.

Earlier, he had told us that street cars aren’t really up to the rigors of racetrack testing: “You can do three or four laps at a time, but that’s about it. The brakes, especially, don’t last. They tend to heat up and fade, and need a rest before they’ll work again. I about ran out of brakes on the Crest yesterday.”

Unfortunately for Team CW, Csaba had managed to turn a lap at 1:33.8 prior to the Viper’s untimely demise. Could the YZF better that mark? After ensuring that there wasn’t any oil on the racetrack, I went out for my timed session, slithering through the bumps and dirt and wrestling with the wind to record a best lap of 1:36.3. Not that shabby considering the circumstances, but pretty pathetic compared to the sub-1:30s that club racers and fast magazine guys regularly turn at Willow. And definitely not quick enough to beat the car.

THE STRIP

When the Viper broke, our plans changed dramaticallyespecially since the only replacement available was plagued by transmission problems, and was loaned to us with the strict proviso that it be used only for photos, and not driven hard. Thus, there would be no timed laps around the Streets of Willow; no skidpad testing (perhaps a blessing in disguise); and no side-by-side performance testing at the dragstrip.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we can’t compare performance figures from previous tests.

As you’d expect, the bike absolutely trounces the car at the dragstrip, covering the quarter-mile almost 2 seconds quicker and 17 mph faster. The bike was similarly superior in braking and top-gear roll-ons, though the latter was due in part to the Viper’s ultra-tall sixth gear.

This last feature (coupled with vastly superior aerodynamics) helped give the 177-mph Viper the nod in the top-speed department, but then, we expected that. And besides, the Viper didn’t have to contend with winds gusting to 30 mph like the YZF did.

After wrapping up our racetrack testing at Willow Springs, we headed to our nearby high-desert testing location to measure the YZF’s top speed. With the wind blowing from the southwest, the bike’s first eastbound pass showed 161 mph on the CIV radar gun. But on its first westbound pass, it only went 138 mph!

Suspecting that the motor was starving for air due to the strong crosswinds, we waited for Mother Nature to calm down a bit before making another pass. And then another. Our best westbound pass wound up being 146 mph, making for a two-way average of 154 mph. Hardly the stuff literbikes are renowned for, but then, conditions could have been better.

THE VERDICT

All in all, a frustrating yet enlightening test. In retrospect, the YZF 1000 probably wasn’t the right bike for the job. The Viper may be billed as a GT car, but it is not a grand-tourer in the traditional sense of the word. To the contrary, its racetrack focus is painfully evident in its noisy interior, firm ride and dearth of luggage space-not to mention that it doesn’t have a locking hood or gas cap!

The YZF, on the other hand, meets the criteria for a grand-touring machine much more readily. Its plush suspension, comfortable passenger accommodations and emphasis on midrange (rather than top-end) power make it far better suited to sport riding than racetrack lapping. It’ll be a sure contender for Best Open Streetbike honors in Cycle World’s 1997 Ten Best voting.

Unfortunately, what we needed for this test was a superbike. A better choice would have been a proven roadracing contender such as Suzuki’s GSX-R750, or a Superbike homologation special like Kawasaki’s ZX-7RR. The Viper GTS is, after all, a limited-production vehicle. With an apparently limited lifespan.

Which raises a sticky question: How can you call a car that blew its motor a “winner?” If anything, we should claim a moral victory for the YZF on the grounds that it still runs (and likely will continue to do so for years to come), or that it costs one-seventh as much as the Viper. It would be interesting to see how a $10,000 (or even a $20,000 or $30,000) car would fare against the $9799 YZF, particularly if the car were carrying four passengers like the BMW in Csaba’s original editorial.

More than any project in recent history, this one left the Cycle World staff with a feeling of unsettled business. So, Car and Driver, what do you say we find out how a Ducati 955 SPO stacks up against a Porsche 911 Turbo? Only this time, let’s run the full 60-mile length of the Angeles Crest Highway, and calculate our racetrack speeds based on an average of, say, 10 laps.

Better yet, let’s compare the two vehicles using a totally different set of parameters. Rather than quantify their performance, let’s rate them according to the enjoyment they provide, on the number of smiles per mile. There’s no way a car would win that contest-at least not until they invent one that wheelies.