SOLD GOLD BSA

STILL RACING AFTER ALL THESE YEARS

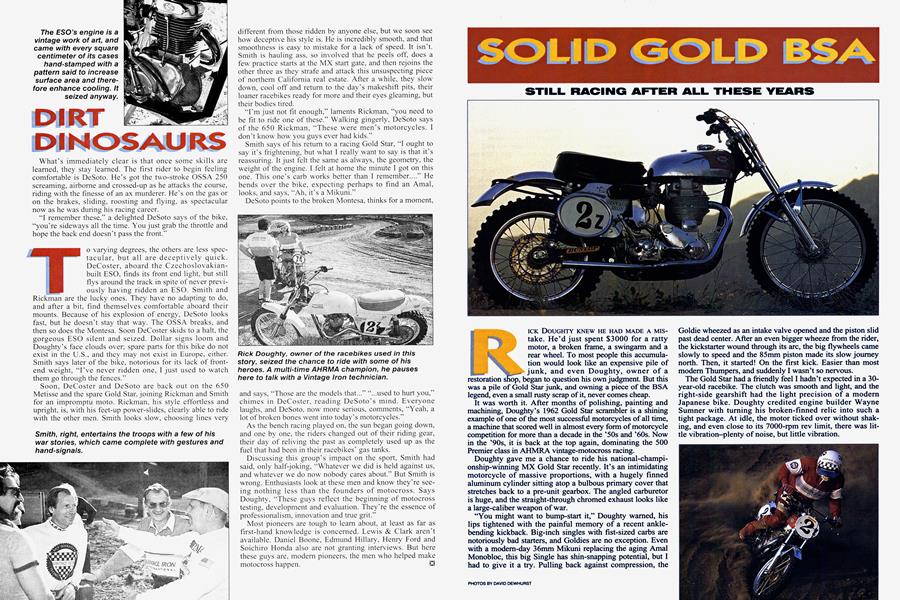

RICK DOUGHTY KNEW HE HAD MADE A MIStake. He’d just spent $3000 for a ratty motor, a broken frame, a swingarm and a rear wheel. To most people this accumulation would look like an expensive pile of junk, and even Doughty, owner of a restoration shop, began to question his own judgment. But this was a pile of Gold Star junk, and owning a piece of the BSA legend, even a small rusty scrap of it, never comes cheap.

It was worth it. After months of polishing, painting and machining, Doughty’s 1962 Gold Star scrambler is a shining example of one of the most successful motorcycles of all time, a machine that scored well in almost every form of motorcycle competition for more than a decade in the ’50s and ’60s. Now in the ’90s, it is back at the top again, dominating the 500 Premier class in AHMRA vintage-motocross racing.

Doughty gave me a chance to ride his national-championship-winning MX Gold Star recently. It’s an intimidating motorcycle of massive proportions, with a hugely finned aluminum cylinder sitting atop a bulbous primary cover that stretches back to a pre-unit gearbox. The angled carburetor is huge, and the straight-through chromed exhaust looks like a large-caliber weapon of war.

“You might want to bump-start it,” Doughty warned, his lips tightened with the painful memory of a recent anklebending kickback. Big-inch singles with fist-sized carbs are notoriously bad starters, and Goldies are no exception. Even with a modem-day 36mm Mikuni replacing thé aging Amal Monobloc, this big Single has shin-snapping potential, but I had to give it a try. Pulling back against compression, the

Goldie wheezed as an intake valve opened and the piston slid past dead center. After an even bigger wheeze from the rider, the kickstarter wound through its arc, the big flywheels came slowly to speed and the 85mm piston made its slow journey north. Then, it started! On the first kick. Easier than most modem Thumpers, and suddenly I wasn’t so nervous.

The Gold Star had a friendly feel I hadn’t expected in a 30year-old racebike. The clutch was smooth and light, and the right-side gearshift had the light precision of a modern Japanese bike. Doughty credited engine builder Wayne Sumner with turning his broken-finned relic into such a tight package. At idle, the motor ticked over without shaking, and even close to its 7000-rpm rev limit, there was little vibration—plenty of noise, but little vibration.

With close to 40 horsepower on tap and a torque curve flatter than Iowa, the Gold Star lunges forward with little more than a gentle growl from the low-mounted exhaust pipe. It feels strong, but not as frantic as a current Husaberg or KTM four-stroke. Big flywheels and an 88mm stroke help the rear Dunlop find traction, even on a hard-baked track. Things can get busy in a hurry, though. The smooth track turns rough and ugly, and I’m reminded that 4 inches of rear-wheel travel, no matter how precisely it’s controlled, can’t compare with today’s long-stroke suspensions. The Gold Star’s modern Works Performance shocks do a great job, but there’s good reason that scrambles used to be held in rolling green fields with nary a stutter-bump or double-jump in sight. The 35mm Ceriani fork with 7 inches of travel is more up to the task, certainly better than the original one-way-damped BSA fork. Still, this is a bike from an era when low weight and long travel were not considered to be an important part of winning, a time when power and traction were everything.

The Gold Star was a master of both power and traction. The big BSA lunges between corners at what seems like an unexceptional rate-no great explosions of power, no frantic wheelspin or dramatic moments-but the next corner rushes toward you at a disarming rate. Throwing off speed for corners calls for a downshift, which turns the Goldie’s massive flywheels into giant inertial brakes, before you bring the brakes-a semi-modem CZ rear drum and a Yamaha front drum-into play. Still, the BSA is a big and heavy piece that confirms all you learned in Physics I0l about objects in motion wanting to stay in motion unless acted on by a powerful external force.

It was in corners, though, that Doughty’s Gold Star defied the laws of physics. It turned, and did so with a precision most modern long-travel bikes don’t enjoy. Better yet, it would slide out of corners like a well-set-up flat-tracker.

The Gold Star legend was getting easier to understand with every lap. Thirty years after its reign ended, the Goldie still has a lot to offer. Semi-modern brakes and suspension have given it a new lease on life. But the heart and soul of the legend, that hulking, big-finned motor, still roared like the world-beating lion it always was. And the rugged BSA frame still tracked as straight and true as ever. Even the much-maligned Lucas racing magneto kept sparking.

Such a machine must have been a racer’s dream come true back in the early Fifties. And now, 40 years later, this Gold Star is Rick Doughty’s dream come true, a solidgold legend that is the most rewarding investment he has ever made. —David Dewhurst

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreen Machines

April 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsYou Ain't Goin' Nowhere

April 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring To Action

April 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha To Go Standard?

April 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupBimota Presses On With Gp Streetbike

April 1993 By Alan Cathcart