Run What Ya Brung

RACE WATCH

Four races, one ace

DAVID DEWHURST

SKI SEASON IS A MONTH AWAY and high in the Rockies just west of Denver there's no sign of snow. Yet the normally quiet streets of Steamboat Springs, one of Colorado’s many ski meccas, are filled with the roar of open exhausts and scented with fine blue clouds of castor-bean racing oil. This is Steamboat’s annual Vintage Bike Week, a time when the summer-sleepy resort town opens its arms to the largest gathering of motorcycle racers in America. A record entry of more than 1000 racers has come for a week of flat-track, trials, motocross and roadracing.

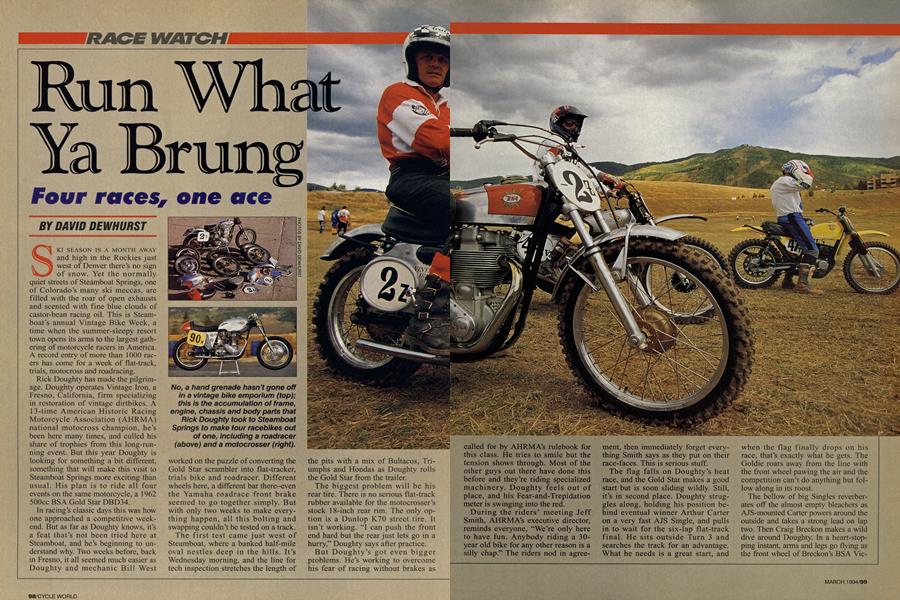

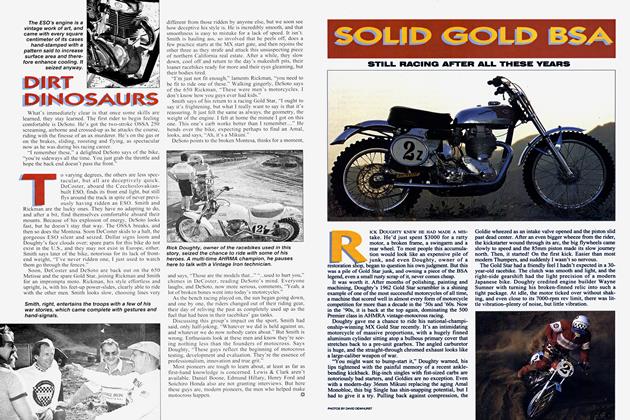

Rick Doughty has made the pilgrimage. Doughty operates Vintage Iron, a Fresno, California, firm specializing in restoration of vintage dirtbikes. A 13-time American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association (AHRMA) national motocross champion, he’s been here many times, and culled his share of trophies from this long-running event. But this year Doughty is looking for something a bit different, something that will make this visit to Steamboat Springs more exciting than usual. His plan is to ride all four events on the same motorcycle, a 1962 500cc BSA Gold Star DBD34.

In racing’s classic days this was how one approached a competitive weekend. But as far as Doughty knows, it’s a feat that’s not been tried here at Steamboat, and he’s beginning to understand why. Two weeks before, back in Fresno, it all seemed much easier as Doughty and mechanic Bill West worked on the puzzle of converting the Gold Star scrambler into flat-tracker, trials bike and roadracer. Different wheels here, a different bar there-even the Yamaha roadrace front brake seemed to go together simply. But with only two weeks to make everything happen, all this bolting and swapping couldn’t be tested on a track.

The first test came just west of Steamboat, where a banked half-mile oval nestles deep in the hills. It’s Wednesday morning, and the line for tech inspection stretches the length of the pits with a mix of Bultacos, Triumphs and Hondas as Doughty rolls the Gold Star from the trailer.

The biggest problem will be his rear tire. There is no serious flat-track rubber available for the motocrosser’s stock 18-inch rear rim. The only option is a Dunlop K70 street tire. It isn’t working. “I can push the front end hard but the rear just lets go in a hurry,” Doughty says after practice.

But Doughty’s got even bigger problems. He’s working to overcome his fear of racing without brakes as called for by AHRMA’s rulebook for this class. He tries to smile but the tension shows through. Most of the other guys out there have done this before and they’re riding specialized machinery. Doughty feels out of place, and his Fear-and-Trepidation meter is swinging into the red.

During the riders’ meeting Jeff Smith, AHRMA’s executive director, reminds everyone, “We’re only here to have fun. Anybody riding a 30year old bike for any other reason is a silly chap.” The riders nod in agree-

ment, then immediately forget everything Smith says as they put on their race-faces. This is serious stuff.

The flag falls on Doughty’s heat race, and the Gold Star makes a good start but is soon sliding wildly. Still, it’s in second place. Doughty struggles along, holding his position behind eventual winner Arthur Carter on a very fast AJS Single, and pulls in to wait for the six-lap flat-track final. He sits outside Turn 3 and searches the track for an advantage. What he needs is a great start, and

when the flag finally drops on his race, that’s exactly what he gets. The Goldie roars away from the line with the front wheel pawing the air and the competition can’t do anything but follow along in its roost.

The bellow of big Singles reverberates off the almost empty bleachers as AJS-mounted Carter powers around the outside and takes a strong lead on lap two. Then Craig Breckon makes a wild dive around Doughty. In a heart-stopping instant, arms and legs go flying as the front wheel of Breckon’s BSA Victor lets go and he falls hard. Doughty somehow manages to stay upright and again hangs on to second place. He says afterwards, “I won’t do this again.”

A seemingly endless list of races continues late into the day, but as Triumph Twins roar wide up to the fence and 250 Bultacos scream side by side in the marbles, the Vintage Iron team has no time to savor the excitement. They are already ripping into the BSA to convert it into a trials bike. New wheels and trials tires are mounted, and the 54-tooth flat-track sprocket is changed to a 56-toother. There’s also a low-mounted front fender, flat bar and new numberplates. It’s the easiest conversion of the week and it’s completed in 41 minutes.

The sky is heavy with rain clouds on Thursday as more than 200 riders await the start of the trial at the base of Steamboat’s ski slopes. FrancisBarnetts, Montesas and Bultacos fill the air with blue smoke and ring-ading-dings, and the noise from AJS, Matchless and BSA Singles booms through the trees. Trialer Barry Higgins comes over and has a quick ride on the Goldie. He comes back with bad news. Compared with Higgins’ specialized Gold Star trials bike, the Vintage Iron entry is geared too high. His advice: “Go wide open and ride it like a motocross course.” This isn’t what Doughty wants to hear, but he cleans the first section. In the second section, he smashes the low-mounted motocross footpegs on a rock and loses his first mark of the day. But Doughty plonks along in the pouring rain and cleans the remaining eight sections on the first lap.

The realization that he might have a shot at victory makes the second lap a bit more daunting. After a couple more cleans, Doughty dabs hard. Two marks down and one more lap to go. The lines for each section are getting long and Doughty uses the time to walk each section, looking for changes. He finds none, but he walks anyway. He starts lap three with a very serious look, and by section 10 he’s still clean.

Section 10 starts up a hill then turns across the slope. Simple, normally, but a large crowd of soggy spectators is watching. They’ve heard that some lunatic vintage ironman is riding four events on the same bike and sense this is important. Doughty senses it, too, and almost chokes. One downhill and a stream crossing are all that stand between him and the perfect lap. As he picks his line through a rutted and difficult water crossing, he’s tense and the bike bogs for a second. A dab seems inevitable. Then Doughty gases it like a motocrosser and makes it, feet up. A clean loop.

The big smile says it all. “Well, that was cool,” beams Doughty. He celebrates with a big long wheelie at the base of Steamboat’s grassy ski slopes. Despite the compromises of low footpegs and tall gearing, it’s been a great day and he’s sure he’s close to victory. But even before the bike’s loaded in the van, there’s another low score. And before Doughty has time to start the motocross conversion, he hears it’s a three-way tie. Ties are broken in an appropriately vintage manner: The oldest guy wins. Roger Ganner and his immaculate Dick Mann-prepared Matchless take home the trophy.

There’s no time to think about what The team has no spares, so mechanic Bill West tightens the springs and everyone goes to bed uneasy. Friday, a thick fog covers the grassy track as the motocross bikes line up for tech inspection. More than 500 riders are entered and the pit area is a sea of old iron. Practice is controlled chaos as an ant-like swarm of motocross weapons does battle. When it’s over, Doughty rolls his mud-covered Goldie back to the van. The clutch seems to be holding up, but, says

Doughty, “It just feels slow. I need more horsepower.” This is the same lament being sung by every rider all week long, as bikes cope with the thin air at 7500 feet. The big Goldie may feel slow, but at the start of the first Premier 500 race, Doughty has the lead to himself. His main competition, Dick Mann, is still in the pits trying to figure why his bike’s engine tried to seize, and there’s little the rest of the runners can do to catch the flying Doughty. The BSA started life as a scrambler. It’s in its natural habitat,

in its perfect set-up. As he stretches his lead, Doughty and the Gold Star dive deep into the turns and drift, feet-up, through the long sweepers. Moto one to the Gold Star. Moto two isn’t much different. The competition’s closer this time, but the result is never in doubt. Doughty and the Gold Star wrap up the Premier 500 motocross championship title. The next

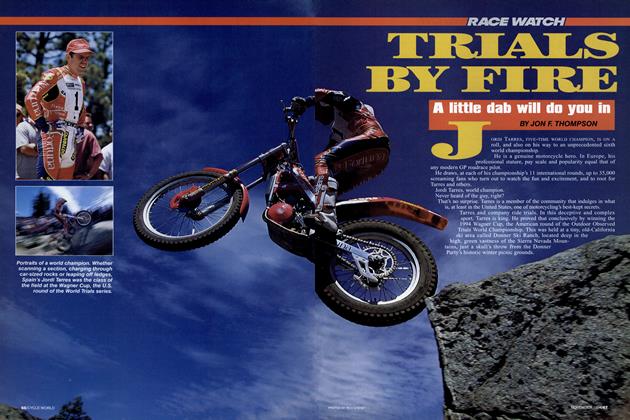

race of the day is barely > Careful, careful. Doughty eases the Gold Star down an incline on the way to a three-way tie in the trials event. In spite of having a healthy respect for the

concept of racing in a class that does not permit the use of brake systems, and in spite of being forced by circumstances to use an inappropriate rear tire on

his bike, Doughty finished second in the flat-track underway when West starts the big conversion from dirt to pavement, with little more than a frame and engine in common between the bike West starts with and the one he ends up with. Boxes of roadrace parts are unpackeda humped seat, huge aluminum gas tank, rearsets, clip-on bars and a new rim laced to a Yamaha 250 roadrace brake. It’s all been bolted up before back at the shop, but here in the field hospital, things aren’t going well.

When the hand-cut brake stays are tightened to the front brake, the backing plates distort, causing the shoes to bind. It takes lots of bending to make things right. The rest of the job soaks up an unexpected amount of time, too.

By midnight it’s nearly finished. That’s when Doughty climbs on and squeezes the front brake. The stanchion tubes rotate in the triple clamps like they’re on ball bearings. At 1:00 a.m. Doughty and West give up. They apply brute force to the triple-clamp bolts. They go to bed worried.

Dark skies in the morning accent the black moods of the previous night. By racetime, water runs down oily new asphalt on the downhill start straight, and snow is falling in the hills behind the hotels. The soggy green flag flies and the Gold Star bolts from the fifth row and hits the tight left-hand Turn 1 in sixth place. Splashing through the puddles using motocross lines, Doughty goes out of sight behind the market and the dry cleaners in fourth place. The deafening roar echoes off the condos as the pack thunders over the bad bump in Turn 7. Race fans look back up toward the hotels and shops that line the last turn and the short front straight. The roar gets louder and suddenly the pack appears out of the spray, the Gold Star leading and opening a gap as it cuts through the standing water.

Rider and bike are giving everything they have, but the soft motocross cam, low gearing and wide transmission ratios are hampering progress. By lap two, Ralph Auer has pushed his BMW R50 into striking position. The battle is on. The gap closes as Auer gains on the fast straights and sweeping turns, while Doughty makes the road as narrow as possible in the slow turns. He’s still got a chance. Auer is equally determined, and he makes his move down the back straight on the last lap. The BSA just can’t match the Beemer for top speed and Doughty glances across as Auer rolls by. He makes one last desperate effort to get back at the end of the straight but only manages to scare himself with a flat-track-style slide in the next turn. He finishes second.

It isn’t a fairytale end to the week, but it’s close. “I thought I’d finish in the top 10,” he shouts as he pulls off the soggy helmet. “Yeah, it was fun.” The adrenaline’s pumping hard and the big, beaming smile shows his excitement. After four tough events Doughty has three second-place finishes and a victory. Spectators walk up and shake his hand. A few even pat the Gold Star. Doughty slaps the big Lyta tank, too.

Someone asks if he’ll do it again next year. “No way,” Doughty replies. After all, he’s ridden all four events on a single bike, and in doing so, has vindicated his “Vintage Ironman” namesake. Next year, it’s someone else’s tum. O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue