Clipboard

RACE WATCH

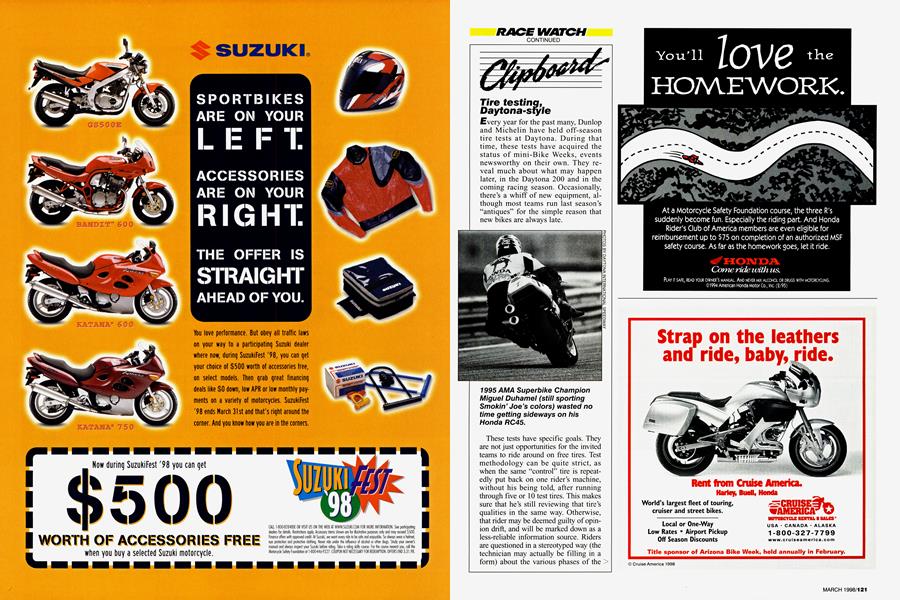

Tire testing, Daytona-style

Every year for the past many, Dunlop and Michelin have held off-season tire tests at Daytona. During that time, these tests have acquired the status of mini-Bike Weeks, events newsworthy on their own. They reveal much about what may happen later, in the Daytona 200 and in the coming racing season. Occasionally, there’s a whiff of new equipment, although most teams run last season’s “antiques” for the simple reason that new bikes are always late.

These tests have specific goals. They are not just opportunities for the invited teams to ride around on free tires. Test methodology can be quite strict, as when the same “control” tire is repeatedly put back on one rider’s machine, without his being told, after running through five or 10 test tires. This makes sure that he’s still reviewing that tire’s qualities in the same way. Otherwise, that rider may be deemed guilty of opinion drift, and will be marked down as a less-reliable information source. Riders are questioned in a stereotyped way (the technician may actually be filling in a form) about the various phases of the > tires’ performance. Tire temperatures are taken in the critical left-of-center strip on which they run on the highspeed, high-centrifugal-load banked part of the speedway. Quite often, full 200mile runs are staged.

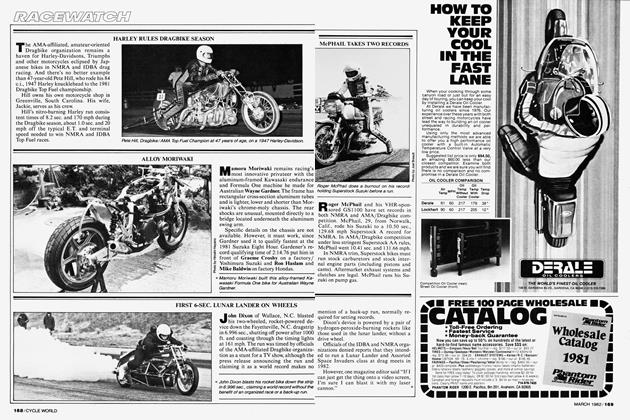

This year, Dunlop’s David Watkins was concerned with eliminating the unscheduled tire stops that had characterized last year’s race. It’s great to win, but the best way to do so is with consistency, with something to spare. The Daytona problem is many-sided. The tires must tolerate high temperature on the banking, but must deliver usable and reliable grip on the less-used right sides of the tires, for which Daytona offers only four turns. The change to multiple-compound construction has helped here, but there still remains the problem of producing a tire soft enough to grip, yet hard enough to last. That is never easy. Tires can fail at the speedway either way. In 1979, Goodyear miscalculated high, and produced the famed “cement tire,” which ran so cool that it hardly worked at all. Veteran racer Mick Grant expressed the view that the entire field would “accumulate in the right-handers” as a result. At the other end lies blistering and chunking. Blistering is the boiling of volatile tread constituents leading to eruptions on the tread surface, loss of material and vibration. Chunking is the loss of large pieces of tread rubber, typically from failure of the tread-to-carcass bond. Both can result from operation above the so-called failure speed. Test tires are run against a drum to roughly eval> uate their operating temperature and failure speed. The failure speed can be raised either by making the tire construction stiffer (reducing flex and, therefore, heating) or by altering the tread rubber to raise the boiling point of its most-volatile component (socalled extender oils and/or waxes). Either of these steps is likely to also reduce grip; the first because it reduces footprint area, the second because it can raise the temperature at which the rubber grips best. Typically, it’s the front tire that shows distress first at Daytona. The front is much smaller than the rear and has a softer compound, but on the banking carries almost as much load as the rear. Jim Allen is Dunlop’s walking encyclopedia of racing in the U.S., the man who sees, remembers and writes down everything of importance that happens with tires at the races. A former topranked roadracer himself, Allen is a valuable asset because he takes his work very seriously, in the racer’s focused “me and my bike” style. If I were a CIA recruiter, I would hire tire men, because they must deal with volumes of information while strictly categorizing all of it according to who may know what. In all, Allen said Dunlop was happy with the test because the top riders got down to uniformly good times quickly, despite there being frost on rental-car windshields the first two mornings, with mid-day temps in the 50s. Former Lucky Strike Suzuki rider Anthony Gobert, on an ex-factory Ducati 996 flown in for Vance & Hines (the front wheel still bore the inscription “P.F. Chili”), touched that “far country” with a 1:49.99 on a qualifying tire, a time also reached by Honda discovery Ben Bostrom, but on a race tire. Doug Chandler on the Muzzy Kawasaki was third fastest at a 1:50.2 on the second day. He banged an ankle and didn’t ride the third day. Pascal Picotte, newly on Harley’s VR1000, got into the high 1:50s, an improvement over the previous best Daytona times for this bike, which has been developed with all deliberate speed. The undeveloped Suzuki TL1000R V-Twin was behind with times in the 1:52s and 1:53s. Allen notes that riders are often disappointed by slower times in March, after setting faster December tire-test times. He believes that the two big NASCAR races, held between those months, are responsible. Car rubber fills in the pavement profile, leaving an artificially smooth surface lacking > in “tooth.” You can actually pick this rubber layer free in some places, pulling away a cast of the pavement.

Although there are differences in how tires run on different bikes, Allen notes that more significant differences are between riders. Miguel Duhamel’s tires always run hotter than Chandler’s, even at the same lap time. At any racetrack other than Daytona, if a Ducati got best results with a medium-compound tire, the four-cylinder bikes might run one of the harder numbers. But at Daytona, the effects of the banking overshadow this; the high speed and the near equality of weight and power of the bikes become more important than the nature of the power delivery.

Hot 600cc Supersport times were also run, with an at-record-pace 1:56.3 by Bostrom, and 1:56.6s by Duhamel and Suzuki’s Aaron Yates.

Michelin has had a reputation for combining outstanding peak grip at full lean, with relatively less warning of where the peak is. Those who have ridden the latest factory Michelins report they are hard to distinguish from Dunlops now, giving clear warning as the limit nears. Michelin riders have been seen to lift their bikes abruptly as they exit corners, to avoid the intermediate lean angles at which these tires have lacked grip. As in finance, assets can be invested in different ways. Shall we make a master’s tire and hope the master makes no mistakes? Or shall we make an everyman’s tire and hope that ease of use equals pointsgetting consistency? The big question (which the Daytona 200 helps to answer every year) is this: Whose way wins championships?

As the Dunlop group left, the Michelin people arrived to inherit rain. A solid band of precipitation covered the state from Tampa to Daytona, limiting the test to a practically useless 2 wet hours one day, l V2 hours the next.

Tom Kipp and Mike Hale were on hand with Fast By Ferracci Ducatis, and Scott Russell got some mileage on what was reputedly a worn-out Yamaha World Superbike. He was heard to remark that “it’s not real fast,” but in the process did a l-minute, 45-second lap (amazing what it does for your lap time when you miss the Chicane). A Michelin staffer was heard to say that at least that showed the tire can take sustained high speed! Another test day may or may not be scheduled.

In sum, the riders got their handlebars and footpegs adjusted, and had their first look of the season at the Chicane and Turn 1, rushing at them like a scary Star Wars screen-saver.

-Kevin Cameron

Rick Johnson back in the saddle

Two-time AMA Supercross Champion Rick Johnson eschewed retirement to contest the annual SCORE Baja/Tecate 1000. Johnson and teammates Matt Barney, James Cloud, Ken Grimsley and Cliff Matlock finished first in Class 30 (for Vets, 30 years of age and older) and fourth overall aboard a mildly modified IMS/O’Neal-sponsored Honda XR628, completing the 770-mile event in 15 hours, 16 minutes and 12 seconds. Besides encountering transmission problems during the last leg of the race, Johnson, currently a part-timer in the NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series, endoed once when he ran into a ditch.

“I think Ricky just wanted to go riding with his buddies,” said American Honda’s Bruce Ogilvie, in charge of pit support. “His times were very respectable, certainly the fastest in Class 30.” Other famous Class 30 competitors included dirt-trackerturned-stuntman Eddie Mulder, who finished second.

Team Honda’s Johnny Campbell, Greg Bringle and Tim Staab won the event in 13 hours, 19 minutes and 59 seconds, topping the once-dominant Trophy Trucks by more than 33 minutes.

Huffman wins world supercross title

ICawasaki’s Damon Huffman won the 1997 FIM World Supercross Championship. The Californian finished the seven-event series with 165 points. France’s Mickael Pichón was second, with reigning AMA Supercross and 250cc National Motocross Champion Jeff Emig third. Jeremy McGrath finished a distant fourth. The World Supercross Championship is Huffman’s third professional title. He won the AMA 125cc Western Regional Supercross Series Championship in 1994 and ’95. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

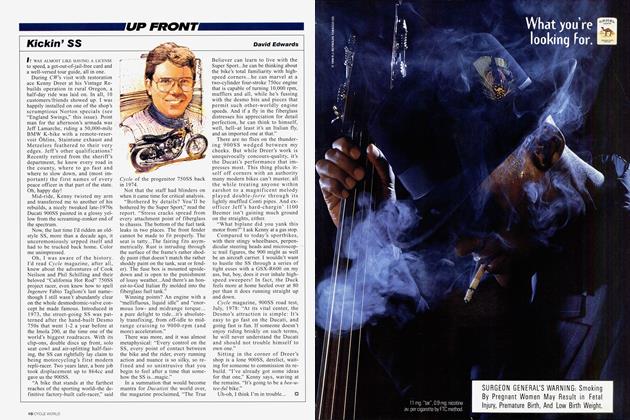

Up FrontKickin' Ss

March 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWinter Storage

March 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

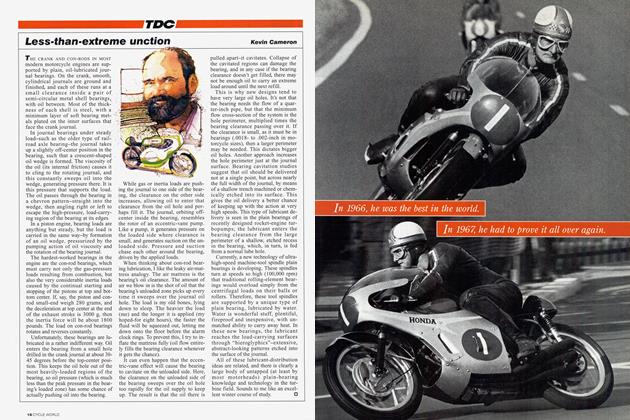

TDCLess-Than-Extreme Unction

March 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1998 -

Roundup

RoundupIntercepted: Honda Vfr800 Impressions From Europe

March 1998 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBikes A Go At the Guggenheim

March 1998