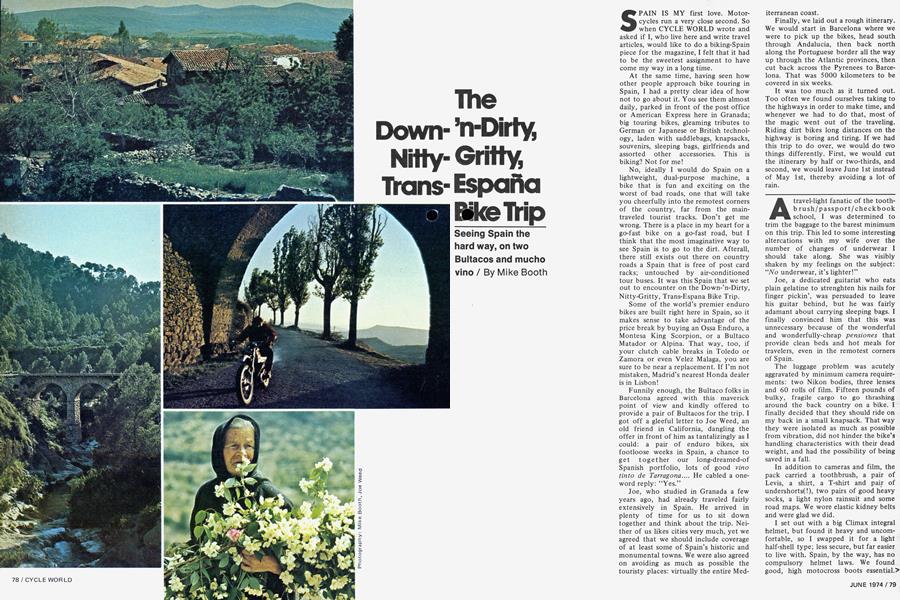

The Down-'n-Dirty, Nitty-Gritty, Trans-España España Bike Trip

Seeing Spain the hard way, on two Bultacos and mucho vino

Mike Booth

SPAIN IS MY first love. Motorcycles run a very close second. So when CYCLE WORLD wrote and asked if I, who live here and write travel articles, would like to do a biking-Spain piece for the magazine, I felt that it had to be the sweetest assignment to have come my way in a long time.

At the same time, having seen how other people approach bike touring in Spain, I had a pretty clear idea of how not to go about it. You see them almost daily, parked in front of the post office or American Express here in Granada; big touring bikes, gleaming tributes to German or Japanese or British technology, laden with saddlebags, knapsacks, souvenirs, sleeping bags, girlfriends and assorted other accessories. This is biking? Not for me!

No, ideally I would do Spain on a lightweight, dual-purpose machine, a bike that is fun and exciting on the worst of bad roads, one that will take you cheerfully into the remotest corners of the country, far from the maintraveled tourist tracks. Don’t get me wrong. There is a place in my heart for a go-fast bike on a go-fast road, but I think that the most imaginative way to see Spain is to go to the dirt. Afterall, there still exists out there on country roads a Spain that is free of post card racks; untouched by air-conditioned tour buses. It was this Spain that we set out to encounter on the Down-’n-Dirty, Nitty-Gritty, Trans-Espana Bike Trip.

Some of the world’s premier enduro bikes are built right here in Spain, so it makes sense to take advantage of the price break by buying an Ossa Enduro, a Montesa King Scorpion, or a Bultaco Matador or Alpina. That way, too, if your clutch cable breaks in Toledo or Zamora or even Velez Malaga, you are sure to be near a replacement. If I’m not mistaken, Madrid’s nearest Honda dealer is in Lisbon!

Funnily enough, the Bultaco folks in Barcelona agreed with this maverick point of view and kindly offered to provide a pair of Bultacos for the trip. I got off a gleeful letter to Joe Weed, an old friend in California, dangling the offer in front of him as tantalizingly as I could: a pair of enduro bikes, six

footloose weeks in Spain, a chance to get together our long-dreamed-of Spanish portfolio, lots of good vino tinto de Tarragona.... He cabled a oneword reply: “Yes.”

Joe, who studied in Granada a few years ago, had already traveled fairly extensively in Spain. He arrived in plenty of time for us to sit down together and think about the trip. Neither of us likes cities very much, yet we agreed that we should include coverage of at least some of Spain’s historic and monumental towns. We were also agreed on avoiding as much as possible the touristy places: virtually the entire Mediterranean coast.

Finally, we laid out a rough itinerary. We would start in Barcelona where we were to pick up the bikes, head south through Andalucia, then back north along the Portuguese border all the way up through the Atlantic provinces, then cut back across the Pyrenees to Barcelona. That was 5000 kilometers to be covered in six weeks.

It was too much as it turned out. Too often we found ourselves taking to the highways in order to make time, and whenever we had to do that, most of the magic went out of the traveling. Riding dirt bikes long distances on the highway is boring and tiring. If we had this trip to do over, we would do two things differently. First, we would cut the itinerary by half or two-thirds, and second, we would leave June 1st instead of May 1st, thereby avoiding a lot of rain.

brush/passport/checkbook travel-light fanatic of the toothschool, I was determined to trim the baggage to the barest minimum on this trip. This led to some interesting altercations with my wife over the number of changes of underwear I should take along. She was visibly shaken by my feelings on the subject:

“No underwear, it’s lighter!”

Joe, a dedicated guitarist who eats plain gelatine to strenghten his nails for finger pickin’, was persuaded to leave his guitar behind, but he was fairly adamant about carrying sleeping bags. I finally convinced him that this was unnecessary because of the wonderful and wonderfully-cheap pensiones that provide clean beds and hot meals for travelers, even in the remotest corners of Spain.

The luggage problem was acutely aggravated by minimum camera requirements: two Nikon bodies, three lenses and 60 rolls of film. Fifteen pounds of bulky, fragile cargo to go thrashing around the back country on a bike. I finally decided that they should ride on my back in a small knapsack. That way they were isolated as much as possible from vibration, did not hinder the bike’s handling characteristics with their dead weight, and had the possibility of being saved in a fall.

In addition to cameras and film, the pack carried a toothbrush, a pair of Levis, a shirt, a T-shirt and pair of undershorts(!), two pairs of good heavy socks, a light nylon rainsuit and some road maps. We wore elastic kidney belts and were glad we did.

I set out with a big Climax integral helmet, but found it heavy and uncomfortable, so I swapped it for a light half-shell type; less secure, but far easier to live with. Spain, by the way, has no compulsory helmet laws. We found good, high motocross boots essential.>

They were fairly uncomfortable to walk in, but in the dirt they saved our feet many times. We considered wearing leathers, but decided against it because of their bulk and the hot weather we expected to encounter.

Both Joe and I also went equipped with a good knowledge of the Spanish language. This was naturally helpful. You can, of course, travel in Spain by staying only in places where people speak English, but it’s a lot less fun. Anyone considering going off the beaten path should make an effort' to learn at least something of the language. The better you are able to communicate with the people you meet along the way, the more rewarding your trip will be.

The humorous myth about Spain’s leave-it-till-manana lifestyle is not mythical, nor is it always humorous to foreigners unaccustomed to the easygoing, three-hours-for-lunch pace here. Although the modern, streamlined, computerized way of life is gaining a foothold in the big cities, most of Spain plods on at a donkey’s pace. A shame you say? Only if you’re trying to place a transoceanic phone call or find spare parts for your electric can opener. On the other hand, if you’re looking for a place to take refuge from phone calls and handy labor-saving gadgets, there probably isn’t a better spot in the world to do it.

Joe and I went out of our way to “go native;” largely avoiding big towns and steering clear of restaurants that looked Howard Johnsony and hotels that looked as though they might have had bourbon on the bar. If you’re going to sit in the cocktail lounge of the Hilton, drinking Jack Daniels and listening to piped-in Herb Alpert, does it really matter whether you’re in Cleveland or Madrid?

The search for nitty-gritty restaurants was Joe’s specialty. He never missed. The places he' picked always served big portions of rich, oily, garlicky vittles with lots of good bad wine to wash them down. (We decided that “bad” wine was like “bad” roads—no such thing). The people we met in these places were down-home types; farmers, construction workers, truck drivers and the like. The conversation tended to be friendly and disarmingly direct. “Where you from?” “Why you got so much hair?” “What does an American carpenter earn?” We always did our best to answer their questions directly and honestly, and usually had to back out of the restaurant, tactfully refusing drinks.

The cally-Spanish expedition start; got a off good to example a typiof the manana syndrome. We arrived in Barcelona on May 1st after a horrific 24-hour train ride from Granada. Bright and early the next morning we were at the Bultaco plant, but the folks there seemed surprised to see us. “You’re here already?” After taking elaborate pains in an extensive exchange of letters to clarify all dates and details,

I was dumbfounded at this wonderfully-Spanish “misunderstanding.” Viva Espanal Go back three spaces.

It seemed that they couldn’t get the bikes to us for another week because it takes that long to license them. We were not about to abandon the project at this point. We waited. The publicity director was very kind; offering the use of his own Alpina for the week.

So the next five days were spent on an unscheduled holiday in nearby Andorra, the tiny mountain country perched on the French-Spanish border 180 kilometers from Barcelona. Andorra has to be for trials bikers what Hawaii is for surfers, or what Switzerland is for skiers. One-hundred-eightyeight square miles of mountains, meadows, trout streams, lakes and pine woods; the best biking trails we found on the whole trip here. They’re mainly old logging trails that have been cut into the mountains over the years by mules dragging logs down. A foot or so deep, and about six feet wide, they are a dirt bike speedway; positively a gas. I was able to borrow a Sherpa-T from an Andorran friend for a couple of days, and Joe and I had a great time chewing through mountain tops.

Our other Andorran discovery was the Hotel Mirador, a small, modestlypriced good hotel with friendly management, French cuisine and a view. Coowner, Claude Marty, a young Frenchman transplanted to Andorra a few years ago, is a professional host with a personal touch, a trout fisherman, an early-rising hunter of mushrooms and, P.S., a mountain biking enthusiast. With very little urging he will take time out from his hotel tasks to show you the Andorran hills.

Back in Barcelona a day early, we stopped by Clice Racing Equipment to get outfitted with boots and gloves. A motorcycle accessories firm begun a few years ago by two enterprising young Bultaco employees, Clice now has a virtual corner on the Spanish accessories market. They even export to the U.S.

At their warehouse, situated at 17 Calle Calabrias, they have everything, and at the friendliest prices you’ve ever seen.

I experienced a feeling of slight uneasiness and deja vu as we walked up the dirt road approaching the back gate of the Bultaco plant. We kept well to the side of the road as nasty little 125cc Pursangs popped out the door of the road test garage and noisily skittered past us, leaving clouds of dust and roostertails of gravel in their wakes.

Pepe Sol, the chief of Bultaco’s final inspection department, greeted us at the door and informed us that both bikes, a > 250cc Matador Mark IV SD and an Alpina of the same displacement, awaited us in his shop, and that they ^^eded just a light going-over before we ^luld leave.

After i Bultaco lunch folks, and we farewells were ready to the to hit the road. The weather was right, the controls on the Alpina nice and tight, the knapsack hung snugly and purposefully on my back, and the ride out of Barcelona was mildly euphoric. Since there are no secondary roads leading out of the city, we soon found ourselves on the main highway south to Tarragona. Before we had gone 35 kilometers, this proved completely unsatisfactory.

The direct experience of the road that makes biking great under ideal circumstances, works in reverse amidst the diesel fumes and traffic of the freeway. In addition, these bikes were not built for sustained high speeds, fchough it will do 100 kilometers per Tiour, above 80 the Alpina sets up a buzzing vibration in your hands, and the gremlin that lives in the seat starts filling your bottom with pins and needles.

On our left the blue Mediterranean was punctuated by signs promoting the Costa Brava vacation paradise and advertisements for mini-golf courses and hotels with diminutive animal names like “Little Seagull” and “Crybaby Crocidile.” We stopped for coffee and got out the map so as to plan our escape route. There is no southbound alternative to the freeway until beyond Tarragona; 60 kilometers further on.

From there we traced a route that would lead us over back roads to a place called Aquaviva; “Livingwater.” The bartender heard us mention the name of the town and laughed. “You know how

éig that place is? Like this,” he said, Idicating the size of a grapefruit with his hands. “There’s nothing there but mountains and fruit trees!” Joe and I looked at each other, shouldered our packs, and were off.

We never did make it to Aquaviva; just as we never made it to a lot of other places we started out for on this trip. The unexpected kept changing our itinerary.

Shortly after leaving the highway south of Tarragona, we made a wrong turn exiting a town called Reus, and as we were turning around, Joe spotted a little covered wagon parked in a grove of carob trees 50 meters off the road.

It belonged to a family camped at the edge of the town. A large tarpaulin fanned off the back of the wagon providing shelter, and a mule grazed serenely nearby. We approached on the

Éikes and a band of incredibly dirtyaced gypsy children appeared in the center of the camp, followed by their father and mother.

We shut off the bikes, dropped our packs, and asked if there was any drinking water in the camp. The wife disappeared and we introduced ourselves to the man, who assumed a formal air as though it were, perhaps, a diplomatic dinner. “Tanto Gusto,” he said, bowing elegantly, “I am called Jose, this is my woman Maria,” turning to his wife who was returning with a clay pipote of fresh water. We drank. Jose looked us over judiciously and examined the bikes. ”Para Montana, ” he said, making a steep slope with his right forearm and sighting along it. He touched the knobby tires, looked

skyward, and exhaled emotively. He and Joe were soon in an animated motorcycle discussion.

It never occurred to Jose to ask what we wanted, or if it did, he was too discreet to say anything. He was perfectly accepting, as though blue-eyed foreigners rolled up every day on strange moto-like machines. Neither was he ashamed of his poverty nor the unusual way in which his family lived. He seemed pleased enough to see us. He was a kind and generous host.

After chatting for awhile, Joe asked if he could take some pictures of the children and I went for some wine. On returning with the wine and some milk and a few groceries, I found seven little gypsies, faces freshly scrubbed, lined up dutifully to have their picture taken. I presented the box of groceries to Maria, who fussed self-consciously, and broke out my cameras.

After shooting half-a-dozen rolls between us, Joe and I stayed to eat a delicious stew of meat and vegetables and chickpeas cooked over an open fire. We were made to promise to return the next morning for coffee before leaving.

It didn’t take us long to find a room and we sat down on the beds facing each other. “Is this what you had in mind for the Down-’n-Dirty, NittyGritty, Trans-Espana Bike Trip?” asked Joe. “Yep,” I replied.

Early the next morning we were back for coffee and an old-friends farewell. Joe asked Jose to what address we might send some prints, and, after a moment’s reflection he said, “I suppose you could send them to my mother in Alicante.”

FI ■ ull Aguaviva. of enthusiasm, The road we were was off paved, for narrow, twisty and hilly. There was no traffic and good visibility through the turns. The morning air smelled piney. At first I was a little wary of the knobby tires on asphalt, but little by little I gained confidence. It surprised me how well the Alpina would hold a corner, and I soon became engrossed in the bike and the road. Choosing an artful line. Smoothly linking up the curves. Shooting through the S-bends

like a racer. Que vida\

From Castellón to Granada is about 650 kilometers. In a reasonably fast car you can drive it in about eight hours. On enduro bikes it’s two days’ hard work. We learned a lesson on this stretch of the trip: The rewards experienced on a bike tour are inversely proportional to the speed at which you travel. That is, the slower you go, the more fun you have.

erhaps because of the great mounW tain terrain, perhaps because of the availability of Spanish trials bikes, Granada is a trials town. On Sundays, when there is no competition within striking distance, the local trials types make excursions into nearby Sierra Nevada. The Sunday we were in town we were invited along on one of these moto-picnics; an easy one this time because it had been decided to take along wives and girlfriends (correction: “wives or girlfriends”).

Our access to Sierra Nevada was up the Camino de los Neveros (“the Icemen’s Trail”), so called because it was the path down which they used to bring ice to Granada before the days of modern refrigeration. For off-the-road bikes it is a highway into these mountains; the highest on the Iberian Peninsula.

An hour’s leisurely ride through the foothills brought us to an abandoned hydroelectric plant sitting in a stand of pines. A couple of Land Rovers were awaiting us and folks were already busy building a fire, lowering crates of beer into the icy river and passing around tapas of a local delicacy, habas con bacalao, raw broadbeans with little chunks of dry salt cod. The nicest thing to be said for this “delicacy” is that it gives one a powerful thirst.

There were maybe 20 bikes on this excursion; Sherpas, Alpinas, Montesa Cota 250s and a Mick Andrews Ossa. There were also a few homemade dirt specials built around 200cc Bultaco engines. These guys have been doing English-type trials riding for a dozen years or more. They know the terrain and they know their machines.

All of this area (all of Spain, for that matter) is criss-crossed by paths made over the years by herds of sheep and goats. “You just pick a likely path and follow it as long as it goes your way,” said Manolo Mangui, president of the local motorcycle club. He made it sound easier than it is. Ever follow a goat up a mountain? Bultaco doesn’t call their trials-type bikes ‘‘motos de montana” for nothing.

I asked David Marshall, a biking friend who lives in Fuengirola, a coastal village beyond Malaga, to show us his neighborhood. He lead Joe and me a^^s country from Fuengirola as far as FI Burgo; much of the way on the track of an old Roman road. We left Fuengirola on a dry riverbed, then wound our way upcountry. From the first high spot where we stopped to take a break, the hills of Malaga province stretched down to the edge of the sea like a green-ongreen patchwork quilt.

(Continued on page 121)

Continued from page 83

David into the delivered village us of triumphantly FI Burgo a couple of hours before sunset; allowing himself time to introduce us to Serafin the innkeeper, have a drink and make it home on the road before dark. Serafin's pension brings up the question of the kind of lodging available to the bike tourer in rural Spain.

It is the smaller of two pensiones in this pueblo of some 25 00 people. Lo-

• d on a side street in the upper ge, it doesn’t even have a sign. To get there you have to ask your way to “la casa de SeraJ'in. ” The rooms are small and tidy. You pay about $2 a night for the room and your dinner, which is served at the family table.

The other place is larger and more prosperous looking and sits on the main street as you enter town. At least two large signs announce that you are approaching the Pension Central. Polks we spoke with in the town said that the food was inferior there and that they charged more. Still, they get virtually all of the tourist trade that passes through FI Burgo, because most foreigners don't know enough to inquire if there is another place t-o stay.

This is the case in almost all Spanish towns. All of the antique charm that we encountered on this trip was in places Serafin’s, which still weren’t quite l^^sperous enough to remodel by replacing the oak with formica and the fireplace with gas heating. In Ubrique (Malaga) we rode all the way to the far end of the town, asked around and were directed to a tiny fonda where a bed and a chicken dinner cost $1.50, including soup, dessert and a bottle of wine. It was upstairs over an old-fashioned bakery and the smell of hot bread permeated everything.

In La Alberca (Salamanca) we bypassed the shiny new hotel on the outskirts of the village and found a pension on the 17th-century plaza. The lady of the house saw that we were chilled from the ride and invited us into the family dining room, built a fire in the fireplace, drew up the table and served us our dinner there.

As we were leaving FI Burgo it ^^ted to rain. Our nylon rainsuits kept tne water out for about 20 minutes. After that, we were wet and cold and a lot like miserable. Motocross tires make riding on wet asphalt even more unpleasant. We never did bother to buy better rain gear, always thinking that this was nearly June in sunny Spain and that the weather had to clear up. Mistake. As we went north the weather got worse, and finally defeated us.

(Continued on page 122)

Continued from page 121

The from rain Jerez changed de la our Frontera, destination the sherry town, to Seville where we could leave the bikes in a Bultaco factory service center for a light going over. (Joe dropped the Alpina off a small cliff onto the rocks below, bending a rear suspension arm, and got on it and rode out. Those bikes seemed nearly indestructible).

The service and hospitality that received from the Bultaco folks Seville were so fine. When we arrived they invited us next door to a sidewalk cafe and kept our glasses full while we told them the story of our trip. We mentioned how well the bikes had performed and they glowed with a pride verging on patriotism. The head mechanic promised us the bikes for the next afternoon. The next morning at 9:00 a boy came to our pension to tell us that they were ready early. We headed right over, but were not permitted to leave until we had coffee and two rounds of brandy. Truly incredible.

Seville is one of Spain’s fabled cities; full of history, gardens and big-eyed girls. It is the most renowned repository of the most characteristic of Andalucian charms. It also has big-town hustle and bustle, noise, traffic and eye-stingin diesel fumes. I couldn’t bring myself) want to stay there very badly. Joe fe the same way, so we headed north towards Merida; the site of Spain’s most extensive Roman ruins.

I’m not much for monuments. They’re usually grey on the outside and damp on the inside. Their atmosphere-, if any, is tainted by groups of cameratoting turistas in Bermuda shorts. But Merida, like Granada with the Alhambra, is one of the monumental towns that can’t be dismissed lightly. Walking into the amphitheater of the restored Roman theater here gives one the feeling of being in ancient Rome.

The next morning Joe had a funny stomach (go to a farmacia, ask for Mexaformo tablets, take two, go back to bed, wait...), so I took the Alpina for a ride through the surrounding countryside. This was Extremadura. The tourist brochures bill it as the land of conquistadores. From here the nob Spaniards set out to lay waste to the New World. Dubious honor, methinks, but then they can hardly bill it as “Spain’s living tribute to feudalism,” \diich, sadly, it is.

rode 10 kilometers across country from Merida to a farm town called Valverde, stopping along the way to talk with a half-dozen farmers and shepherds. Their stories were all similar and they aroused in me a moral indignation that I haven’t experienced since I was a sophomore in college.

“Valverde is a large township and all the land is owned by five men. We shepherds live with our families in straw huts. There’s no life here. Our sons all leave for the factories in Bilbao, Barcelona or Germany....”

“And what about the 18 year old I just spoke with, the one who is tending your sheep down there?” I interjected, trying to look on the bright side.

“He’s illiterate, there’s no place for him to go. And those aren’t our sheep.

aey |hs 20 belong duros to a day the for Señorito. tending My them.” son This dehesa stretches for as far as the eye can see in three directions. It is not the only farm the Señorito owns, nor is it the biggest. The Señorito lives in a castle. Not a large house. A castle.

Sad land, Extremadura. The pigs eat acorns.

The dusk next to the day’s edge ride of the brought province us of at Salamanca at the foot of the Sierra de la Pena de Francia. The last 20 kilometers the dirt road rose more than 3000 feet in an exhilarating series of switchbacks. Joe and I had a great time playing motocross, and arrived at dark at a little mountain town called La Alberca. This was the place where the innkeeper’s wife set us a table by the fire.

^■Jne could hardly pick a better introduction to Old Castile than La Alberca. The town dates from the 15th century; many of the present houses are from the 17th and 18th. The narrow, cobbled streets and crooked old Tudor-style houses looked like something out of Hansel and Gretel.

Joe and I spent the next morning shooting in the streets of La Alberca, then headed for Salamanca, 78 kilometers further on. It was our intention to spend the afternoon photographing this most acclaimed of historic Spanish towns. We arrived, had a beer near the Plaza Mayor, and strolled through the university towards the cathedral. Joe said, “More churches, huh?” I had been thinking the same thing. “Yeah, let’s go.”

It was only 65 kilometers north to

«mora, b a pension, and we take arrived a bath in time and to go check to a nine-o’clock movie. Perhaps because Zamora is a dull town, perhaps because we were anxious to see Spain’s Atlantic provinces, we set out early the next morning, cutting across the northeast corner of Portugal towards Galicia.

(Continued on page 124)

Continued from page 123

We were only in Portugal for about four hours, but it was a hassle changing money and talking pidgin Portuguese, and we were happy to re-enter Spain at a town called Feces. You can believe that or not. We stayed in Verin, a few kilometers on. Verin is distinguished for its good Gallego cooking, astonishingly beautiful girls and “Sweet Virginia” on the jukeboxes.

There was a good bad road which meandered from Verin toward Vigo on the coast, and we twisted our way down it, stopping frequently to photograph folks in the fields and villages. The country folk here are small and brighteyed and wear absurd outsized shoes. They are no doubt the descendents of Celtic gnomes and hobbits who migrated to this region centuries ago.

Vigo is a town I could learn to love. With its hills and harbor, its old tram tracks and good fishing spots, it’s like San Francisco, but without all those San Franciscans. It’s a fishing town and all of the ambiente emanates from the port where little boats arrive with fresh shellfish and big boats deliver hake and cod from as far away as the Canaries. We stayed here for two days and between-shooting sessions around the harbor and the town, managed to get the bikes washed and the oil changed and our laundry done. Evenings were spent in waterfront bars like the Montevideo, that are frequented by fishermen and students.

A short Santiago way de out Compostela, of Vigo towards the sky turned slate gray and it began to rain. That rain followed us more or less constantly for the next week. The rain will wear you down, friends. But we were determined to complete the last stage of our journey; up through Asturias and the Basque country to the foot of the Pyrenees and then along the mountains from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean.

We rode on. It continued to rain. It rained in Santiago; we toured the bodegas with a law student who was a wine expert and a dirt bike enthusiast. It rained in Pola de Allande; we photographed an old-fashioned bakery and ate hot bread. It rained on the way to Salas; we took refuge under a bridge and built a fire. It rained in Oviedo; we went to the movies.

Out of Oviedo the rain stopped and we hotfooted it to a Basque fishing/ tourist village called Orio, 20 kilome^^ short of San Sebastion. We were dead tired when we arrived—having done nearly 400 kilometers of highway riding—but after a bath we were out strolling through the town. We were drawn into a bodegon by the odor of charcoal-grilled sea bass, the specialty here. Near us was a table of young people. A slender fellow with a rakishly-trimmed beard came over to our table and asked in a friendly way if we were Americans. He had been a merchant seaman and spoke some English. He invited us to join them for dessert.

(Continued on page 128)

Continued from page 124

One young man at the table seemed strangely out of place. He was younger than the others and had a lost, scared, feather-in-the-wind look. Was I imagining things? We talked. They were members of E.T.A., the militant Basque nationalist movement. They describj^ their experiences for us. Lots bravado: police searches, machine guns, night border crossings on foot, and so on. The do gets more derring after the third brandy. The young one was with the group, it seemed, because his father had been implicated in the kidnapping of a Spanish industrialist and had had to take refuge in France. I am always the skeptic. But a look at that boy’s face, trying to put on a smile....

The next morning we were both worn out, but we were within striking distance of the Pyrenees and anxious to get started. We rode through San Sebastian almost to Irun, then turned off at Oyarzun. The road immediately started to wind its way up a tree-lined river valley. After the touristy, industrial atmosphere of the coast there was a welcomed peacefulness. The edge of the

road was dotted with the parked cars^^

Sunday picnickers. Children were play^ ing with a beach ball by the edge of the stream.

Joe and I stopped the bikes, breathing easy even though rain was threatening again, and decided to stop at the first grocery store and buy the makings for a picnic. We bought too much, found a spot off the road, made a fire and roasted longaniza sausage and pork chops on sticks. The vino bianco was cold and the bread tasted sweet.

The level of the wine dropped quickly to the bottom of the label and we were struck by a wave of lucidity that lasted fully ten minutes. In this brief time we reviewed our lives past (high school principal droning in an assembly, “You will look back on these as the best days of your lives...”) and present (Weed nearly tipping over the wine bottle and catching it for t^B fourth time...). We talked about Spain, elaborated a philosophy of art, and tIW vainly to translate dulce de membrillo into English. We bought too much; ate it all. Smashing picnic.

(Continued on page 130)

Continued from page 128

Reluctantly we put out the fire and packed up. The road widened and got exhilaratingly faster for some 30 kilom eters. We stopped for coffee in a road side inn full of people noisily stuffing themselves with roast goose and turnips. The coffee tasted like coffee should.

A really great dirt road took us from the next pueblo, Irurita, 20 kilometers to Eugui, negoti ating a cloud-bound mountain pass enroute. The day was cool and leaden gray. The road took us up, up into an eerie mist.

Suddenly, at the exit of a blind left-hand curve, appeared a loose group of green-caped figures spaced along bo sides of the road, bearing carbines a machine pistols. Parked at the roadside were two 400cc Sanglas motorcycles and a green Land Rover with the yellow Guardia Civil insignia. One of the caped f~rni ri~c ii r~ve~r

I counted seven agents of the police. There was a large oak tree and a flock of sheep grazing peacefully. Surreal. Put ting on a too-loud, good-natured voice I ventured, "Lots of shepherds for so few sheep, gentlemen!" Nobody laughed.

One agent, a young one with pim ples, face as stupid as a parakeet's, stepped clear, unveiling his carbine, as I reached inside my coat for the docu ments. We were high on one side of a long valley. The other side is France. I remembered the frightened face of the fragile young man in the restaurant and the stories his corn paneros had to tell.

Then rain and rain again the n& day. The third day dawned rainy and w had had enough. We headed south from Pamplona towards Granada. It took two days to reach Madrid, where we had the bikes serviced.

Heading out of Madrid, a big black cloud chased us down across La Man cha, but we beat it to Despenaperros Pass and slipped happily into sunny Andalucia, leaving the rain to flail at Don Quixote's windmills. By seven we were home in Granada. Sweet Granada. The Alpina rolled into my yard purring like a kitten. The odometer ticked over 4800 kilometers.

Looking back, I think that the best commentary on the trip was made by a pair of bartenders we talked with in a bar off the Plaza Mayor in Salamanca. They asked how far we had come. We told them. "Vaya!" Said one: "To mak a trip like that on a motorcycle takes sense of humor." Si, hombre!" added the other, "y mucha ilusion...."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAct Sane In Spain Or Don't Get On the Plane

June 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1974 -

Departments

Departments"Feedback"

June 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

June 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Competition

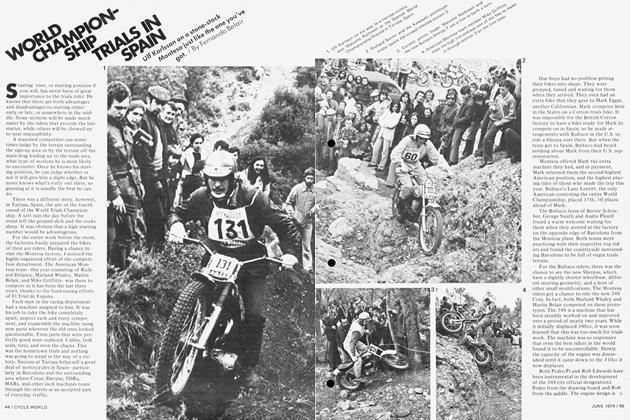

CompetitionWorld Championship Trials In Spain

June 1974 By Fernando Belair -

Features

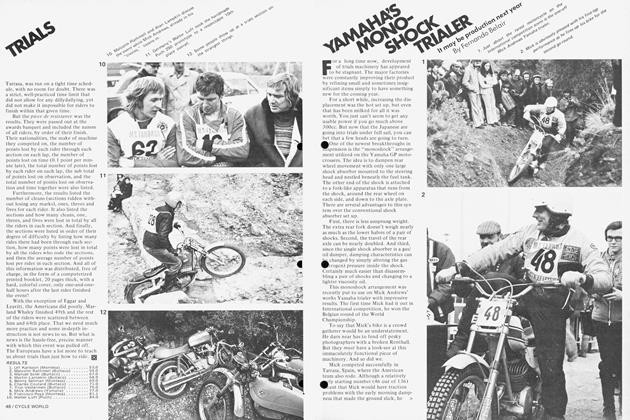

FeaturesYamaha's Monoshock Trialer

June 1974 By Fernando Belair