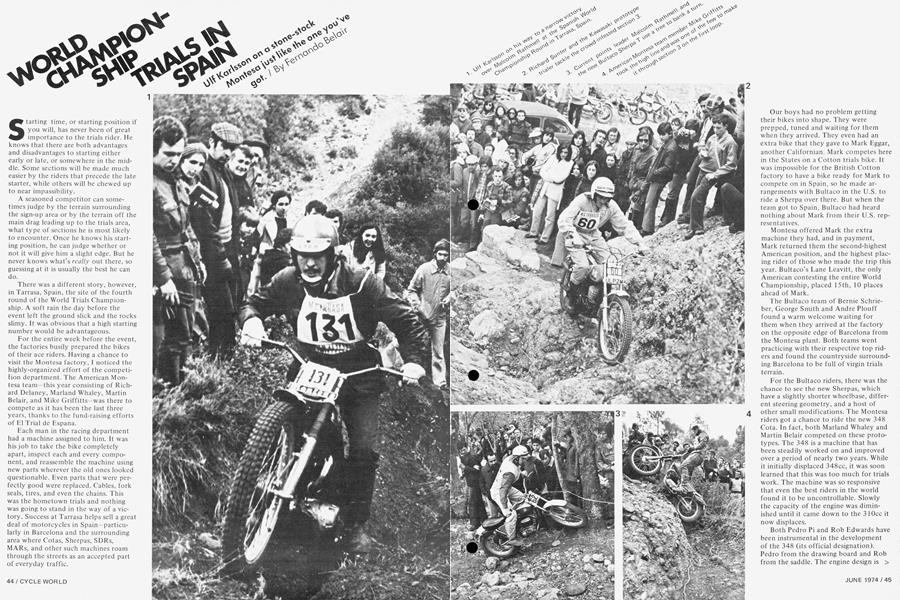

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP TRIALS IN SPAIN

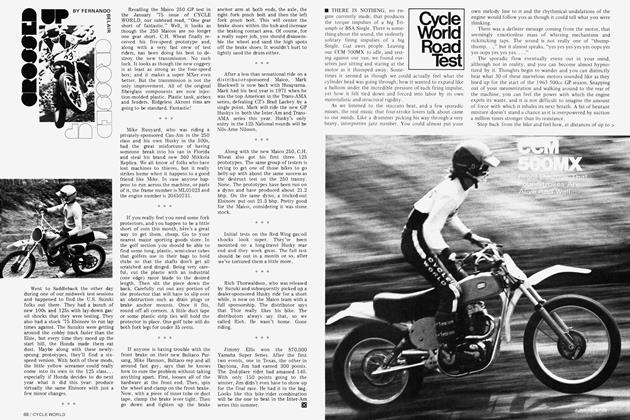

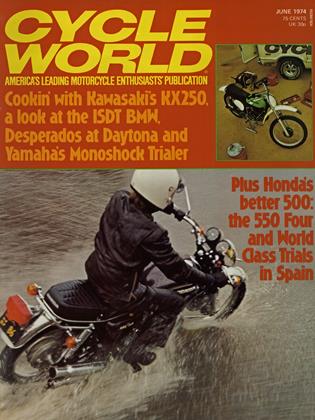

Ulf Karlsson on a stone-stock Montesa just like the one you've got.

Fernando Belair

Starting time, or starting position if you will, has never been of great importance to the trials rider. He knows that there are both advantages and disadvantages to starting either early or late, or somewhere in the mid dle. Some sections will be made much easier by the riders that precede the late starter, while others will be chewed up to near impassibility.

A seasoned competitor can some times judge by the terrain surrounding the sign-up area or by the terrain off the main drag leading up to the trials area, what type of sections he is most likely to encounter. Once he knows his start ing position, he can judge whether or not it will give him a slight edge. But he never knows what's really out there, so guessing at it is usually the best he can do. There was a different story, however, in Tarrasa, Spain, the site of the fourth round of the World Trials Champion ship. A soft rain the day before the event left the ground slick and the rocks slimy. It was obvious that a high starting number would be advantageous.

For the entire week before the event, the factories busily prepared the bikes of their ace riders. Having a chance to visit the Montesa factory, I noticed the highly-organized effort of the competi lion department. The American Mon tesa team-this year consisting of Rich ard Delaney, Marland Whaley, Martin Belair, and Mike Griffitts-was there to compete as it has been the last three years, thanks to the fund-raising efforts of El Trial de Espana.

Each man in the racing department had a machine assigned to him. It was his job to take the bike completely apart, inspect each and every compo nent, and reassemble the machine using new parts wherever the old ones looked questionable. Even parts that were per fectly good were replaced. Cables, fork seals, tires, and even the chains. This was the hometown trials and nothing was going to stand in the way of a vic tory. Success at Tarrasa helps sell a great deal of motorcycles in Spain-particu larly in Barcelona and the surrounding area where Cotas, Sherpas, SDRs, MARs, and other such machines roam through the streets as an accepted part of everyday traffic.

Our boys had no problem getting their bikes into shape. They were prepped, tuned and waiting for them when they arrived. They even had an extra bike that they gave to Mark Eggar, another Californian. Mark competes here in the States on a Cotton trials bike. It was impossible for the British Cotton factory to have a bike ready for Mark to compete on in Spain, so he made ar rangements with Bultaco in the U.S. to ride a Sherpa over there. But when the team got to Spain, Bultaco had heard nothing about Mark from their U.S. rep resentatives.

Montesa offered Mark the extra machine they had, and in payment, Mark returned them the second-highest American position, and the highest plac ing rider of those who made the trip this year. Bultaco's Lane Leavitt, the only American contesting the entire World Championship, placed 15th, 10 places ahead of Mark.

The Bultaco team of Bernie Schrie ber, George Smith and Andre Plouff found a warm welcome waiting for them when they arrived at the factory on the opposite edge of Barcelona from the Montesa plant. Both teams went practicing with their respective top rid ers and found the countryside surround ing Barcelona to be full of virgin trials terrain.

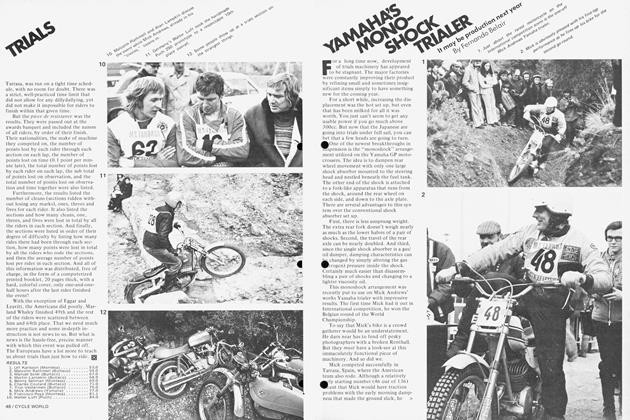

For the Bultaco riders, there was the chance to see the new Sherpas, which have a slightly shorter wheelbase, differ ent steering geometry, and a host of other small modifications. The Montesa riders got a chance to ride the new 348 Cota. In fact, both Marland Whaley and Martin Belair competed on these proto types. The 348 is a machine that has been steadily worked on and improved over a period of nearly two years. While it initially displaced 348cc, it was soon learned that this was too much for trials work. The machine was so responsive that even the best riders in the world found it to be uncontrollable. Slowly the capacity of the engine was dimin ished until it came down to the 3 10cc it now displaces.

Both Pedro Pi and Rob Edwards have been instrumental in the development of the 348 (its official designation). Pedro from the drawing board and Rob from the saddle. The engine design is > pretty well settled, but with the increased power and totally different torque characteristics, the need for a new frame arose. This is still in the experimental stage and it will probably be a year or so before you see a production 348 Montesa Cota.

Edwards competed on the 348 prototype for the first time in Belgium after his brilliant victory in Ireland the week before. He finished 6th. In Spain he would finish a disastrous 23rd, but it was all done for only one reason: to test the machine more, to put it through its paces again, trying to find whatever bugs might exist before the machine is released to the public.

The machine is both brutally powerful and beautifully docile. It all depends on what the rider’s right hand does. Because of the increased displacement, the 310s are using the lower ends from older Montesa’s, which had heavier flywheels than the current models. The extra flywheels are what’s been bothering Edwards. A rider who has reflexes as finely hewn as Rob’s are, finds it more difficult to maintain his level of proficiency on a machine with different power characteristics than a rider of less ability does. Rob, who is still appealing his disqualification from the American round (through the ACU in England), has an excellent chance of becoming World Champion this year. If he does not, it will probably be a result of the transition time that he is spending adapting to the new Cota. This is the extreme sacrifice that a factory rider must pay in the interest of the consumer.

At the actual event in Tarrasa, the riders all showed up early. Two Americans, Belair and Whaley, were among the first to leave, taking off on the sixth and twelfth minutes, respectively, after 9 a.m. For these first riders the sections were slippery and difficult. Even the Europeans who drew low numbers found traction limited. Martin Lampkin left on the 1 1th minute and found the going much more difficult than teammate Yrjo Vesterinen, who left on the 124th minute.

But the big story came neither from the big name riders nor from the special factory bikes. It came from a very tall, gangly-looking Swede named Ulf Karlsson. Karlsson looks like one of those guys you knew in high school who was about 6 ft. 8 in., but was never coordinated enough to play basketball. But coordination is one thing Ulf doesn’t lack. He utilizes every inch of his body size to put his Montesa exactly where he wants it. His heft is also helpful when placed over the rear wheel for traction.

And it was obvious that Ulf got more traction than anyone else. At least in the first eight sections. Here the Swede, who drew number 131, amassed a grand total of two points, while 2nd-place finisher Malcolm Rathmell floundered around, gathering 14 marks. Ulf managed to pull two more marks ahead of Rathmell to a first lap lead of 25 to 41. But Rathmell rode an unbelievable second loop, dropping only 13 points in the 24 sections, where no one else could even break 20. In the end, Karlsson, riding an out-of-the-crate Cota, beat the current points leader 53 to 54. The fact that Ulf, and 5th-place finisher Benny Sellman, rode standard machines points out the true competition readiness of stock trials machinery.

Apart from Karlsson’s victory, there were a few more surprises at Tarrasa. Manuel Soler, a young member of the extensive Bulto clan, owners of Bultaco, finished 3rd overall. Manuel has been a highly-praised rider who, because of his age, has not been allowed to compete in world class events until this year.

The age problem was one that plagued an American rider too. Bernie Schrieber is only 15 years old, yet is the number two Master in California. Bernie knew that there was a chance that he would not be allowed to compete in Spain if he went, since he is not old enough to obtain an FIM license. But he hoped that he would be allowed to ride “outside the event” just as he was allowed to do for the U.S. round at Saddleback. Unfortunately, an FIM jury did not see it the same way we had here in the States, and the young pilot was denied a chance to compete. So Bernie joined the hundreds of “followers” who rode the loop with the riders, just to see them tackle all of the sections. The number of such followers was the only thing that any of the Europeans complained about.

The event, staged by the Motor Club > Tarrasa, was run on a tight time schedule, with no room for doubt. There was a strict, well-practiced time limit that did not allow for any dillydallying, yet did not make it impossible for riders to finish within that given time.

But the piece de resistance was the results. They were passed out at the awards banquet and included the names of all riders, by order of their finish. Their nationalities, the make of machine they competed on, the number of points lost by each rider through each section on each lap, the number of points lost on time (0.1 point per minute late), the total number of points lost by each rider on each lap, the sub total of points lost on observation, and the total number of points lost on observation and time together were also listed.

Furthermore, the results listed the number of cleans (sections ridden without losing any marks), ones, threes and fives for each rider. It also listed the sections and how many cleans, one, threes, and fives were lost in total by all the riders in each section. And finally, the sections were listed in order of their degree of difficulty by listing how many rides there had been through each section, how many points were lost in total by all the riders who rode the sections, and then the average number of points lost per rider in each section. And all of this information was distributed, free of charge, in the form of a computerized printed booklet, 20 pages thick, with a hard, colorful cover, only one-and-onehalf hours after the last rider finished the event!

With the exception of Eggar and Leavitt, the Americans did poorly. Marland Whaley finished 49th and the rest of the riders were scattered between him and 64th place. That we need much more practice and some in-depth instruction is not news to us. But what is news is the hassle-free, precise manner with which this event was pulled off. The Europeans have a lot more to teach us about trials than just how to ride.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue