YAMAHA'S MONOSHOCK TRIALER

It may be production next year

Fernando Belair

For a long time now, development of trials machinery has appeared to be stagnant. The major factories were constantly improving their product by refining small and sometimes insignificant items simply to have something new for the coming year.

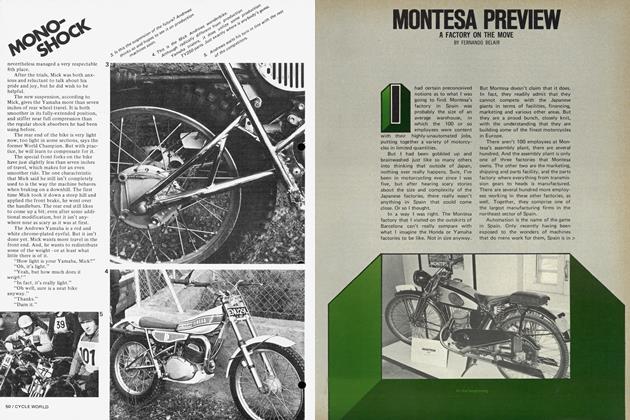

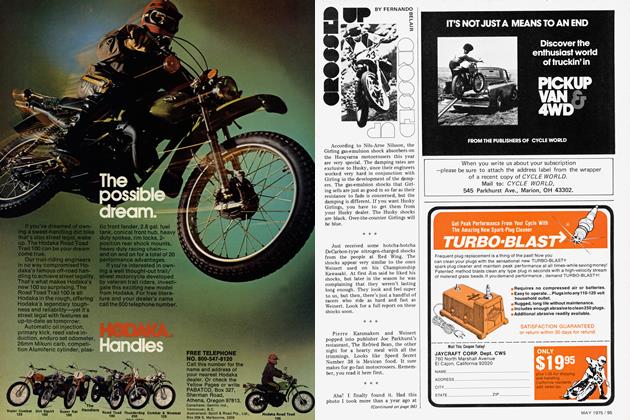

For a short while, increasing the displacement was the hot set up, but even that has been milked for all it was worth. You just can’t seem to get any usable power if you go much above 300cc. But now that the Japanese are going into trials under full sail, you can bet that a few heads are going to turn. ^^One of the newest breakthroughs in ^fspension is the “monoshock” arrangement utilized on the Yamaha GP motocrossers. The idea is to dampen rear wheel movement with only one large shock absorber mounted to the steering head and nestled beneath the fuel tank. The other end of the shock is attached to a fork-like apparatus that runs from the shock, around the rear wheel on each side, and down to the axle plate. There are several advantages to this system over the conventional shock absorber set up.

First, there is less unsprung weight. The extra rear fork doesn’t weigh nearly as much as the lower halves of a pair of shocks. Second, the travel of the rear axle can be nearly doubled. And third, since the single shock absorber is a gas/ oil damper, damping characteristics can J^changed by simply altering the gas ^Phrogen) pressure inside the shock. Certainly much easier than disassembling a pair of shocks and changing to a lighter viscosity oil.

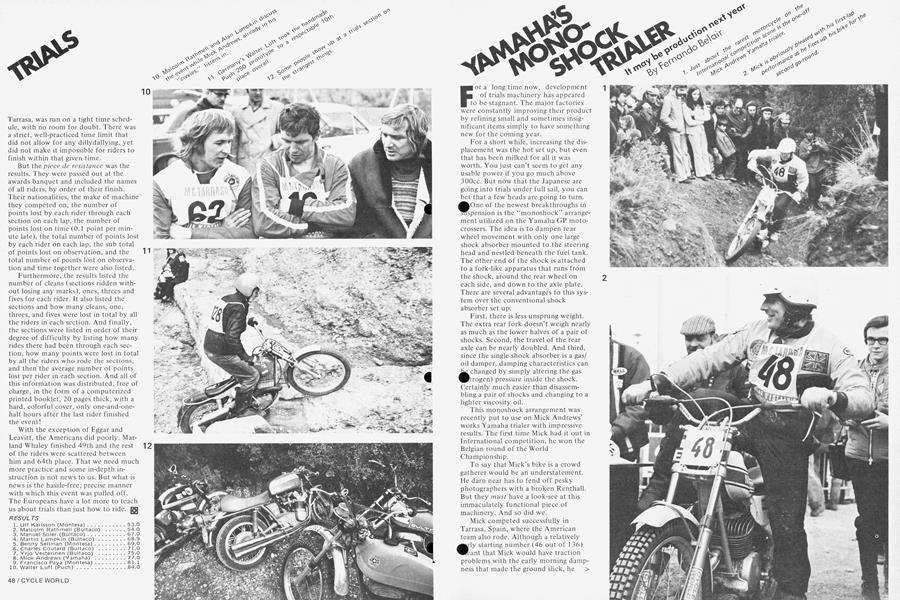

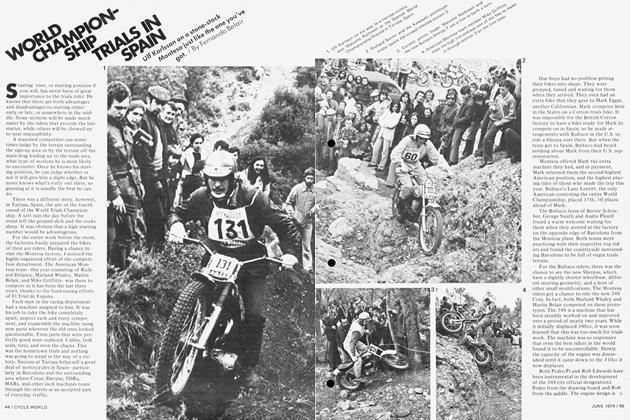

This monoshock arrangement was recently put to use on Mick Andrews’ works Yamaha trialer with impressive results. The first time Mick had it out in International competition, he won the Belgian round of the World Championship.

To say that Klick’s bike is a crowd gatherer would be an understatement.

He darn near has to fend off pesky photographers with a broken Renthall. But they must have a look-see at this immaculately functional piece of machinery. And so did we.

Mick competed successfully in Tarrasa, Spain, where the American team also rode. Although a relatively ^uJy starting number (46 out of 1 36) ^Rant that Mick would have traction problems with the early morning dampness that made the ground slick, he > nevertheless managed a very respectable 8th place.

After the trials, Mick was both anxious and reluctant to talk about his pride and joy, but he did wish to be helpful.

The new suspension, according to Mick, gives the Yamaha more than seven inches of rear wheel travel. It is both smoother in its fully-extended position, and stiffer near full compression than the regular shock absorbers he had been using before.

The rear end of the bike is very light now; too light in some sections, says the former World Champion. But with practice, he will learn to compensate for it.

The special front forks on the bike have just slightly less than seven inches of travel, which makes for an even smoother ride. The one characteristic that Mick said he still isn’t completely used to is the way the machine behaves when braking on a downhill. The first time Mick took it down a steep hill and applied the front brake, he went over the handlebars. The rear end still likes to come up a bit; even after some additional modification, but it isn’t anywhere near as scary as it was at first.

The Andrews Yamaha is a red and white chrome-plated eyeful. But it isn’t done yet. Mick wants more travel in the front end. And, he wants to redistribute some of the weight—or at least what little there is of it.

“How light is your Yamaha, Mick?”

“Oh, it’s light.”

“Yeah, but how much does it weigh?”

“In fact, it’s really light.”

“Oh well, sure is a neat bike anyway.”

“Thanks.”

“Darn it.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue