BIG BIKES, BRAVE MEN

How yesterday's Open Class TT recers became the fashion statement of today

ALLAN GIRDLER

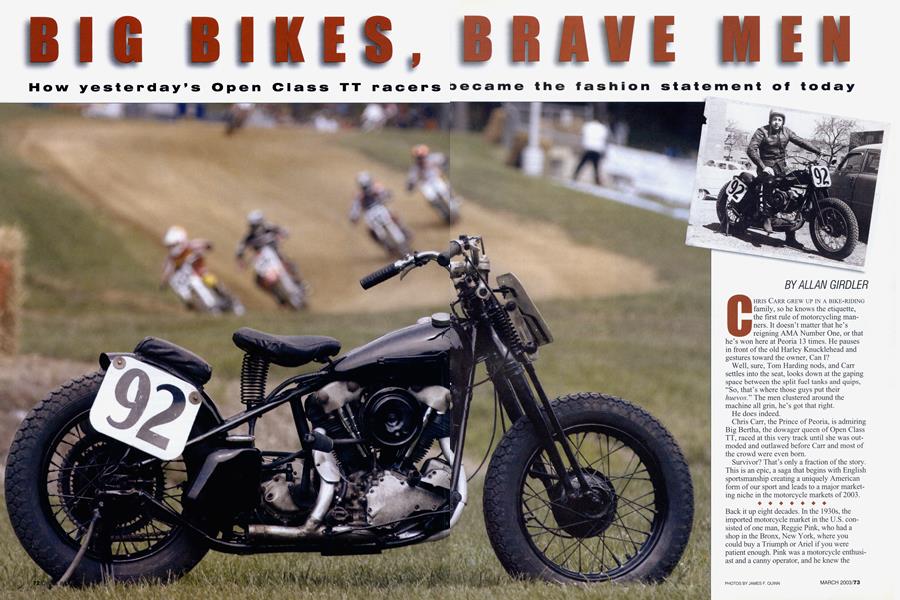

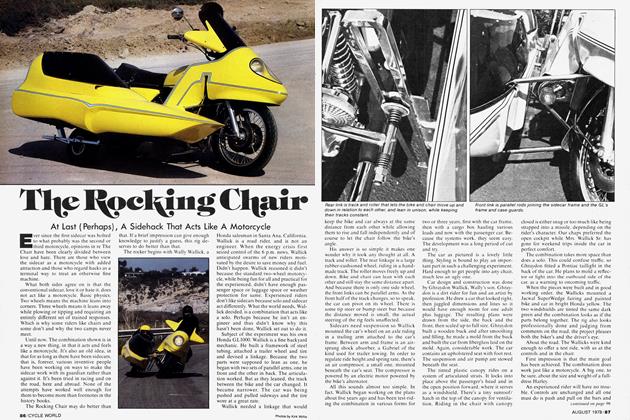

CHRIS CARR GREW UP IN A BIKE-RIDING family, so he knows the etiquette, the first rule of motorcycling manners. It doesn’t matter that he’s reigning AMA Number One, or that he’s won here at Peoria 13 times. He pauses in front of the old Harley Knucklehead and gestures toward the owner, Can I?

Well, sure, Tom Harding nods, and Cansettles into the seat, looks down at the gaping space between the split fuel tanks and quips, “So, that’s where those guys put their huevos.” The men clustered around the machine all grin, he’s got that right.

He does indeed.

Chris Carr, the Prince of Peoria, is admiring Big Bertha, the dowager queen of Open Class TT, raced at this very track until she was outmoded and outlawed before Carr and most of the crowd were even bom.

Survivor? That’s only a fraction of the story. This is an epic, a saga that begins with English sportsmanship creating a uniquely American form of our sport and leads to a major marketing niche in the motorcycle markets of 2003.

Back it up eight decades. In the 1930s, the imported motorcycle market in the U.S. consisted of one man, Reggie Pink, who had a shop in the Bronx, New York, where you could buy a Triumph or Ariel if you were patient enough. Pink was a motorcycle enthusiast and a canny operator, and he knew the secret to keeping a dealership in business was for the dealer to provide something for his customers to do with their machines.

One day, Pink and some members of the Corona Motorcycle Club laid out an irregular circuit in an apple orchard in rural New York. The course was scraped dirt, up hill and down, so it wasn’t flat-track and it wasn’t roadracing and it wasn’t cross-country.

Pink, a huge fan of the Isle of Man, named the ensuing competition after that tiny island’s biggest race, the Tourist Trophy, quickly shortened to TT. Soon, the American Motorcycle Association got wind of this fledgling form of racing and decided that TT seemed like a great way to spend Sunday afternoons, so with Pink’s permission, the AMA magazine circulated the rules and format, and TT became part of the sport. Still is, with two TT nationals on the GNC circuit.

TT racing was a big hit. Machines ran in one of two classes: traditional Class C for production-based 750cc Flatheads and overhead-valve 500s (out of deference to Pink and his beloved Britbikes) or Open Class for the big 74-inch (1200cc) jobs. The course could be laid out almost anywhere a club could borrow a pasture. Before and after WWII, there were tracks all across the country, but TT was especially popular in the Midwest-Ohio,

Illinois, Indiana-and in Texas and California. Virtually every county in these states had at least one TT track, sometimes AMA-sanctioned and sometimes not. Roger Söderström, the original Prince of Peoria because he won the Open Class there in 1949, ’52 and ’53, and both classes in 1950, says you could race all summer long, several times a week.

Which brings us to the machine we see here. Notes from the board meetings of The Motor Company in the early ’30s don’t show any concern with TT, or even racing. The founders were more interested in keeping the company in business. But they knew their business, their sport and their customers. In 1936, Harley-Davidson introduced the Model E, the 61-inch (lOOOcc) overhead-valve V-Twin quickly and permanently known as the Knucklehead. By the standards of the time, it was a sporting middleweight. It was smaller than the sidevalve Harley VL or Indian Chief, it had more power and stamina, and it looked right.

The Open Class racers who could afford one, got one, and they did the usual modifications, as in floorboards replaced by pegs, handlebars raised so the rider could stand up over jumps, big saddle tossed in favor of a solo seat, with a pad on the rear fender to allow a crouch on the straights. There was even a technique known as “bumping,” in which the frame was bashed and reshaped until the front end was kicked out, for clearance and stability.

H-D delivered improvements. The E engine got heads with larger ports and a bigger carb in 1940, then came the 1200cc FL engine, bigger bore and longer stroke, in 1941.

So it happened that in 1946, Jerry Kiesow, an auto mechanic, and George Moody, an Indian dealer, acquired most of a 1936 EL-most because it was a ’36 frame with a lOOOcc Knucklehead engine and not much else. They bored it, then cut down FL flywheels to fit in the E cases, but kept the original camshaft because what were radical specs for the smaller engine provided useful torque from the big engine. Moody was the tuner and did the standard modifications, as in ported and polished heads, siamesed exhaust pipes tucked beneath

the engine and a Wico magneto in place of the generator. Fork tubes came from the XA, Harley’s prototype built for the military, because XA forks were longer and stronger, which raised and kicked out the front wheel. They used an 18-inch rear wheel and a 19-inch front, with stock brakes. The front fender was removed and the rear fender came from H-D’s WR 750 parts book.

Kiesow converted the rocker clutch to a “suicide” arrangement-like a car clutch, springloaded to engage when you lift your foot. He picked a pair of saddle tanks, painted black.

When Kiesow retired from racing in favor of family and farm, Moody did some extra tuning and painted the machine yellow and green. He seems to have been a showman, with a WR in the same colors. He named the 750 “Sweetpea,” and the Knucklehead “Big Bertha.”

Here’s where the world changes. Söderström says the best part of riding the Open Class TT machines was the sheer, raw, stupendous power of the beasts. But the Big Twins were high and wide, with hardly any suspension and they required riding skills unique to the sport. Because they had more power than they could put on the ground, quick laps meant using only the power that could be used.

Söderström, who won the big races and should know, says the winning technique was not to spin the rear tire-you had to learn how to slide without leaning into the turn.

Say what? The speed secret in flat-track now is learning to lean beyond what Newtonian physics allows. How can you slide without leaning?

You had to, Söderström counters, because if you dragged solid parts on the ground, the rear wheel jacked itself off the track and you were through for the day. At best.

Fully aware of the Knuck’s limitations as a racebike, in 1952 Harley-Davidson introduced the KHR-TT, an Open Class racer based on the new street K-model, later to evolve into the Sportster. Triumph had the Bonneville, an ohv 650 that was a match for the 883cc side valve KHR, while both new models had rear suspension, telescopic forks, hand clutch and foot shift, and both were lighter and more nimble than the Knuckleheads.

In 1948, the Open Class national at Peoria finished 11 seconds quicker than the 750 class. In 1950, when Söderström won both, he was only 1.5 seconds quicker on his Knucklehead. And in 1952, the winning KHR-TT was faster than Soderstrom’s big bike.

Jack Potter didn’t care. In 1953, he decided he’d watched the races long enough, so the home-schooled engineer who worked in the experimental department at Caterpillar Tractor-pause for the he-must-have-felt-right-at-home-onthe-Harley jokes-went TT racing. Moody had sold the outmoded Big Bertha to H-D dealer and racer Bruce Walters, who in turn moved it along to Potter.

Who set to work. He checked out the engine just to be sure it was right, then fitted a hand clutch, pulling the same linkage as did the foot clutch, still in place. The mod was just for starts, he says now: You pushed the hand-shifter forward at the startline, used the clutch lever for a quick getaway, then switched to the foot clutch and hauled back into top, simple as that.

Bertha’s bulk or age didn’t discourage Potter. Highlights of his career: 1) Won a Pro main while still rated as a Novice-in those days you could run with the Pros if you qualified fast enough, as he did. 2) Gave the Triumph factory team such a drubbing at an Illinois State Championship TT that Triumph’s manager protested Bertha’s engine, which was declared legal.

3) Raced against Söderström, his hero, and won, head-to-head, fair and square-after the race Söderström lived up to his reputation by coming over and offering his hand in congratulations.

4) In 1960, the final season before the AMA banned Open Class TTs in favor of 900s, he was the last man to compete in a national aboard a Harley-Davidson Big Twin.

With that, Jack Potter hung up his leathers. When he retired from Caterpillar, he ran away to the West and became a hunting and fishing guide in Wyoming, which is where he is at this writing. He sold the outlawed Knucklehead to current owner Tom Harding, a Peoria MC member and physics professor.

This is the low point of the saga. Before he could do anything with the old warrior, Harding was hit head-on by a drunk driver as he left the clubhouse on his road bike. He didn’t fully recover for several years, and the only racing he did with Big Bertha was at the drags, where the hand clutch came in handy. And he admits to some spirited road rides-too much so, he allows now, because he hit a railroad crossing too hard and fast, and bent the 19-inch front rim, which is why there’s an 18-inch wheel there now.

Then, the bike was parked. But about 15 years ago, Harding got back to work. He set out to return Big Bertha to her earlier form, replacing Potter’s peanut tank and Moody’s fancy paint with black paint and saddle tanks. He kept the low, sidemount oil tank, because it was authentic racing gear from the time.

He also did some freshening. The solo seat was ripped and worn, but Harding had an old leather jacket, black of course, and he cut and fit panels from that, so the seat looks old but good.

As an individual exhibit, Big Bertha is a hit. Parked in the pits at the Peoria TT 2002, she draws an admiring crowd, and generates the comment, direct quote here, “That’s the bike Jack Potter used to race.”

That’s a pretty good tribute, 42 years after retirement.

But wait, there’s culture.

First, make a list of what the big TT bikes featured-kickedout fork, skinny front wheel, tiny tank, skimpy seat and rear pad, fat rear tire, high bars.

Next, remember that back in the 1950s and early ’60s before the start of “The Sixties,” motorcycle clubs were momand-pop affairs, and what mom and pop did was put stuff on their motorcycles. So, what the younger guys did, to be sure nobody thought they were mom and pop, was take stuff off.

Plus, no one’s ever thrown away a Harley-Davidson. When the Big Twins were banned from the track, they were put back on the street, or parked in the back of the shop. WTien the counter-culturists, the guys who were taking stuff off, needed inspiration, there was that distinctive profile, the elements of speed and power, so that became the fashion of the street.

Thus, when a young Willie G. Davidson was instructed to make as many new bikes, so to speak, as could be done with as little straw as possible, he went out on the street, and the big TT profile was what he found.

And what he used, with the frame and engine from the FLH and the Sportster’s skinny front end and some distinctive fiberglass, to create the 1971 FX Super Glide. In The Motor Company’s book, the profile became The Look.

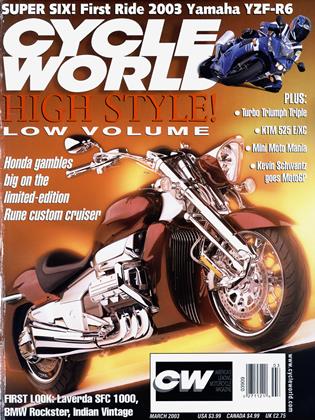

It sold. The Look appealed to a segment of the market; the Super Glide became the Super Glide family. When Yamaha wanted to save money the Harley-Davidson way, a new look from as many old parts as possible, they introduced the Custom, which became a surprise best-seller and inspired all the other versions, leading to the term “Cruiser,” and now we have all those cruisers and clones and copies, hundreds of thousands of motorcycles, visible any time the weather’s good, all with a version of The Look.

And it all came about because a dealer who shared his customers’ enthusiasm came up with something new to do on Sunday afternoons.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

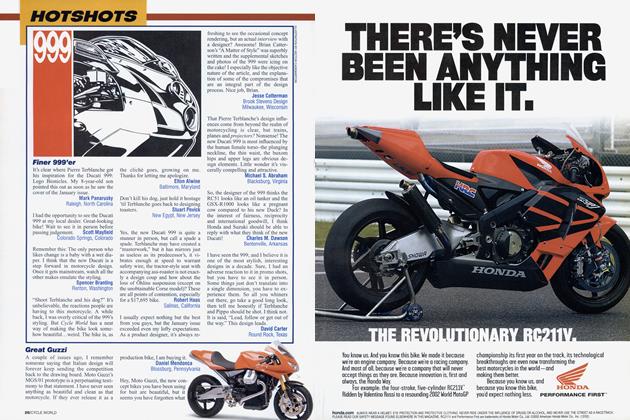

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

Roundup

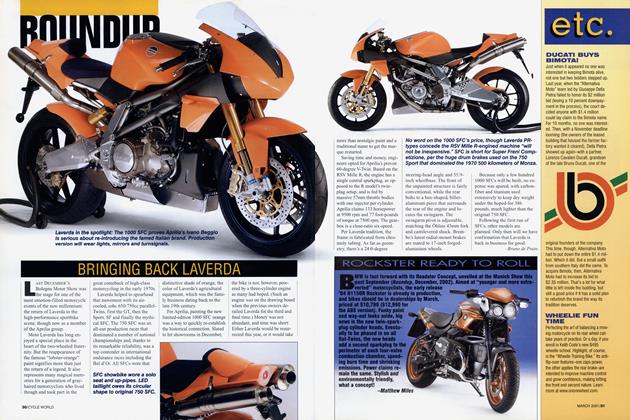

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles