Bill Mitchell

The most audacious car designer of the 20th century had a secret: He loved motorcycles

JOHN L. STEIN

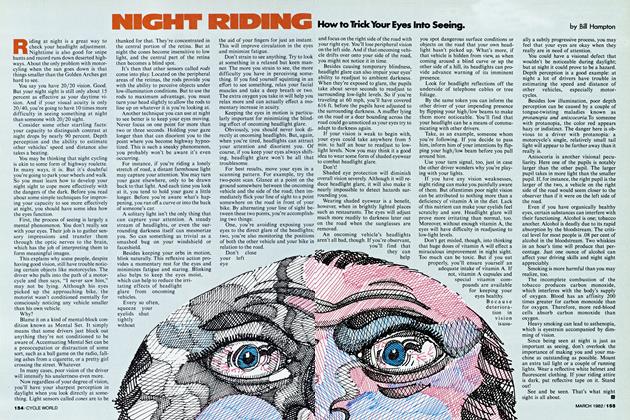

FOR MOST OF THE 20TH CENTURY, MEN LIKE BILL Mitchell, Harley Earl and Raymond Loewy ruled American industrial design. In stark contrast to today, the empires at General Motors and elsewhere guaranteed that head designers were virtually untouchable by management, and thus extremely powerful. At the peak of his career, Bill Mitchell, an artist, experimenter and motorcyclist at heart, was exactly that. He shaped the teams that shaped automotive greats like the 1963 and 1968 Corvette Sting Rays, the original Buick Riviera, the 1967 Camaro, the postwar “torpedo” Buick fastbacks and others. His designs were often rakish and lavishly decorated, but they always paid homage to Mitchell’s credo: “I want a car to look like it’s going like hell even when it’s sitting still.”

From about 1971 until 1981, Mitchell also applied his design talents to a host of motorcycles. He clearly appreciated bikes for the aura, style and potency they projected. He was extremely powerful and influential in the world of automotive design-it is said that his designs saw the light of day on 72.5 million cars. But one block over, on the motorcycling playing field, he was a relative newcomer. Though it didn’t stop him from trying.

Besides working through the backdoor at the GM Tech Center, he had a shop north of Detroit, where GM Design staff employees helped bring the bikes to life. When racers and motorcycle manufacturer executives visited, he’d bring them to the shop. “What do you think of this? Here, try this out.

Here’s what you should be building.” He held his visions that strongly.

Mitchell’s take on the world was that styling and presentation equaled substance.

Whereas racers know that deeds equaled substance. And yet, curiously perhaps, motorcycles offered a middle ground that attracted both archetypes. All sorts of liaisons were the result: Mitchell’s GM Design employees designed a motorhome for Kenny Roberts, a custom bike-carrying pickup that Roger Penske supposedly wanted but could not buy, and even a crew chase vehicle for Evel Knievel.

Rich Yakubison, then an experimental model-maker at GM, worked on some of the bikes shown here. “We did clays and took the casts off the clays,” he said. “We even formed the windshields and taillight lenses by heating Plexiglas over plaster molds.”

Mostly, Mitchell had tank/body/seat combinations fabricated, sometimes including fairings or other elements, and often matching GM production or concept cars. There usually seems to be a lack of engineering components to his work, reinforcing the notion that Mitchell’s view of motorcycling was cosmetic rather than functional. Still, Mitchell rode each and every one of his bikes, and regularly attended the Indy 500, Daytona, Road America and other racing events with them.

Arguably, a few of the bikes were dazzling and the others simply parallels to themes being explored by Paul Dunstall, Craig Vetter and the rest. Still others appear half-baked-especially compared to cars like the seminal split-window Sting Ray coupe.

Bill Nichols, powertrain engineering manager for Corvette and Camaro, is also a motorcyclist. He says refinement comes from living with the design for a while. Whereas Mitchell designed his bikes on a whim, built them and then went onto the next one, cars meant for production spent years going from renderings to clays to committees and clinics before approval. The bikes were done fast according to the designer’s whim.

Mike Lathers, former chief designer for GM commercial vehicles, explains, “Bill was a phenomenal guy in that he explored everything. Not all of them were winners, but look at the range of the shapes. GM enjoyed success because Bill Mitchell was constantly exploring.”

Mitchell designed and had built perhaps 20 motorcycle specials based on Harley-Davidson, BMW, MV Agusta, Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha, Ducati, Moto Guzzi and Laverda. He carefully chronicled his finished bikes, and often set-up photo shoots for them.

He also worked hard at creating a thematic link between the power and performance of bikes and cars. Two wheels, four wheels: Mitchell saw them as fraternal twins, uniquely different but borne of the same DNA. Whether you like Mitchell’s results or not, what other designer or company is doing that today? BMW, Honda and Suzuki are certainly capable, but the two disciplines never connect.

When Mitchell left for the hospital before dying of heart failure in 1988, he had been at work in the basement studio at home. He left his glasses on the drafting table along with an unfinished rendering. At 76 years old, he never grew tired of it. It is this sense of enthusiasm that is most impressive. In the end, he had worked at design for over a half century.

What remains today are Mitchell’s vehicles, his influence, and his indomitable spirit. Above all else, he was irrepressible. As Mike Lathers says, “Bill Mitchell didn’t care who the hell you were. He’d take you on.”

HAVE YOU SEEN THIS BIKE?

I NEVER MEANT TO GO DOWN THIS BlLL Mitchell road. But last year, friend Tod Rafferty e-mailed me, “Did you see this ad?” An L.A. man was selling an unfinished 1974 Ducati 750 Sport. I’m a sucker for unfinished bikes, and since Sports don’t grow on trees, I decided to call. Paul Garson answered the phone.

“It had this bizarre body on it,” he started. “All one piece and beautifully crafted. White, with a rectangular headlight, square taillight from a car, handlebars poking through slots in the fairing, and sidepanels with vents shaped like gills.”

It sounded a lot like the Cyndi Lauper of motorcycles. “Go on,” I said.

Garson recalled he bought it from a friend of a friend of a pilot, who had gotten the bike from someone in lieu of money owed. Garson thought the bodywork was too strange for street use, though he made an effort to trace it. “I wrote to the Ducati owners club about 10 years ago and they ran a photo in the newsletter,” Garson recalled. “Someone wrote that it was a Mitchell design bike.”

When I arrived, the bike wore 750 Super Sport livery Garson had found at an Oregon shop. And where was the trick bodywork? “I gave it away at a yard sale,” Garson confessed. “Some

artist wanted to turn it into a lamp or table or something.”

If indeed it’s a Mitchell creation, the Sport may deserve reconfiguring. So if you’re an L.A. artist with a bizarre coffee table featuring shark gills and a square taillight, or a Michigander who remembers the bike prowling the suburbs, e-mail me at autoauthor@aol.com. Just do so quickly, will you? Because until then, the thing’s cluttering up this

-------— 3— -3-’

-John L. Stein

View Full Issue

View Full Issue