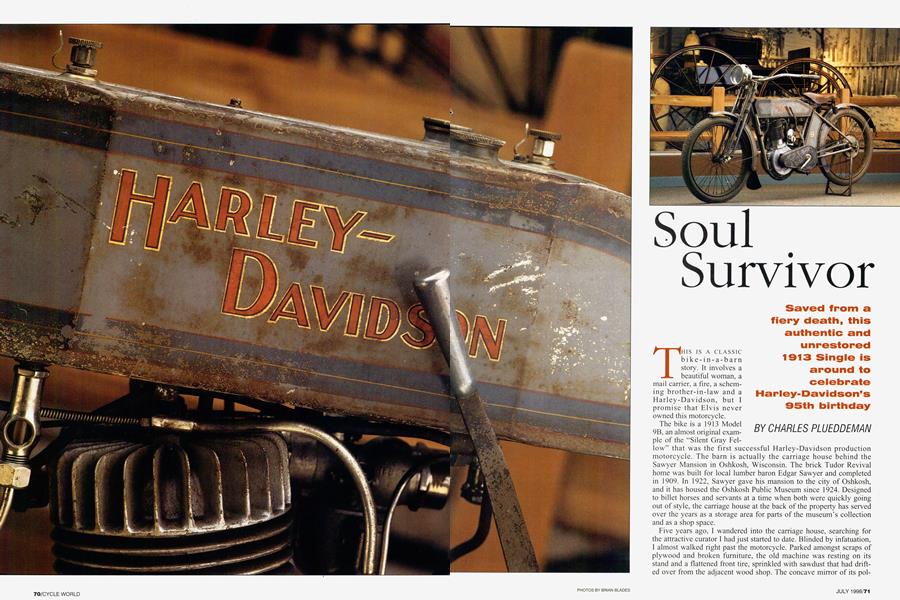

Soul Survivor

Saved from a fiery death, this authentic and unrestored 1913 Single is around to celebrate HarleyDavidson's 95th birthday

CHARLES PLUEDDEMAN

THIS IS A CLASSIC bike-in-a-barn story. It involves a beautiful woman, a mail carrier, a fire, a scheming brother-in-law and a Harley-Davidson, but I promise that Elvis never owned this motorcycle.

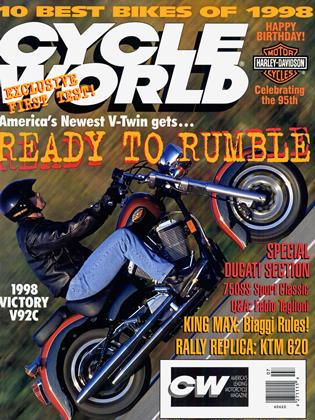

The bike is a 1913 Model 9B, an almost original example of the "Silent Gray Fellow" that was the first successful Harley-Davidson production motorcycle. The barn is actually the carriage house behind the Sawyer Mansion in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The brick Tudor Revival home was built for local lumber baron Edgar Sawyer and completed in 1909. In 1922, Sawyer gave his mansion to the city of Oshkosh, and it has housed the Oshkosh Public Museum since 1924. Designed to billet horses and servants at a time when both were quickly going out of style, the carriage house at the back of the property has served over the years as a storage area for parts of the museum's collection and as a shop space.

Five years ago, I wandered into the carriage house, searching for the attractive curator I had just started to date. Blinded by infatuation, I almost walked right past the motorcycle. Parked amongst scraps of plywood and broken furniture, the old machine was resting on its stand and a flattened front tire, sprinkled with sawdust that had drift ed over from the adjacent wood shop. The concave mirror of its pol ished headlamp reflected my image upside-down, and the morning sunlight that shone through glass panes in the big sliding doors behind the bike illuminated a familiar hyphenated logo on the flat side of the fuel tank.

Paternal instinct quickly overwhelmed lust, and I wondered if I could just push the old Harley home and take care of her. That, it was firmly explained, would be impossible. Nobody at the museum seemed very interested in the motorcycle, but they were not interested in getting rid of it, either. What a shame, I thought, for this neat old bike to be relegated to such a dusty, insecure existence.

The carriage house turned out to be the safest place for the Harley. On June 2, 1994, workers repairing the slate roof of the mansion started a fire that destroyed the third-story area where most of the museum's collection was stored. Smoke and water damage ruined all of the exhibits on lower floors. The carnage house, and the Model 9B, remained miraculously intact.

The fire was just the latest twist in the mysterious history of this Harley-Davidson, which has now been conserved and is the centerpiece of the restored museum's first new perma nent exhibit, just in time for this summer's Harley-Davidson 95th Anniversary celebration.

T he year 1913 was a time of banner sales for HarleyDavidson. Thanks in part to the completion of a new factory on Juneau Avenue in Milwaukee, pro duction jumped to 12,996 from just 3852 bikes in 1912, relieving pent-up demand for which the 1913 brochure apologizes: "Despite the fact that we.. .were the largest manufacturers of single-cylinder motorcycles in the world, we were unable to supply the demand." Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

One of the bikes produced in the new plant was a 1913 9B purchased by Fermin Shaw, a 38-year-old postman working an RFD route near Tomah in rugged Monroe County about 100 miles west of Oshkosh. At the time, Harley-Davidson was promoting its motorcycles as a transportation alterna tive for rural mail carriers and telephone linemen, who still used horse-drawn vehicles to make their rounds. The 1913 Harley-Davidson brochure claims that, "One man with a motorcycle could do the work of from three to five men with teams." On a good road, the Model 9B was capable of a breathtaking 50 mph. Fitted with the optional "Universal Luggage Carrier" over the front wheel, the motorcycle may have seemed to Shaw like an economical and speedy way to deliver the mail.

Priced at $235, the 1913 Model 9B had new features that made it better suited than previous Harley models to profes sional use. Most significant was the advent of chain drive, which debuted in 1912 on a few examples of the 9B and the V-Twin 9E, but was widely available in 1913. The chain and clutch replaced the 1~-inch flat leather belt that drove previous Harley models. The leather belt transmitted power smoothly and worked well in dry conditions, but slipped ter ribly when it was wet.

To make chain-drive practical, William Harley devised "Free Wheel Control," a multi-plate dry clutch located in the rear wheel hub, engaged with a hand lever on the left side of the fuel tank. This allowed a mail carrier to start and stop with ease along his route. He started the engine of the 9B moped-style, pumping a set of bicycle pedals to spin the back wheel with the bike on its rear stand before engaging the clutch to bump-start the engine. Backward pressure on the pedals engaged a Thor coaster brake in the rear hub that provided minimal stopping power. A double-sided fuel tank, perhaps the stylistic origin of the modern Fat Bob tank, neatly covered the upper frame tube, holding 6 quarts of gas and 3.5 quarts of oil for the total-loss oiling system.

The 9B was powered by the sturdy "5-35" engine. A 35cubic-inch Single rated at 5 hp at 2450 rpm, the 5-35 stayed in production until 1918. The iron head and cylinder were cast as a single part and mated to an aluminum crankcase. The engine was introduced in 1908 with a mechanical exhaust valve and an atmospheric intake valve, which was little more than a flap per pushed closed by the compression of the rising piston. In 1913, the 5-35 received a pocket-type mechanical intake valve that helped the engine run smoother without the flutter that plagued the atmospheric valve at higher rpm. -

Harley-Davidson had introduced the leading-link fork in 1904, and the 1913 9B had the latest design. The 9B has a hardtail frame, and in fact the 1913 brochure goes to great length-almost a page of copy-to discredit the "spring frames" that were on the market, with statements like, "To cut the frame in two or to hinge it is to court danger." Instead, Harley-Davidson offered the "Ful-Floteing Seat." The seat post slid up and down in the seat tube, suspended by a spring within the tube. Spring tension was adjustable for rider weight, and the range of travel was nearly 4 inches.

The Harley owner could choose from several saddle styles when outfitting his bike. In fact, as early as 1913 Harley Davidson was busy selling its owners accessories. The parts manual recommends using only Harley-Davidson Special Oil (sound familiar again?). A separate catalog of acces sories includes lamps, tanks, generators, tires, tools, pumps, speedometers, sparkplugs, pennants and even jerseys, the first Motor Clothes.

he outcome of Fermin Shaw's experiment with the Harley-Davidson 9B is a mystery, but it seems that it was not successful. When the museum delivered the bike late in 1997 to the shop of conservator Ralph Kennedy, it was still rolling on its original white-rubber Goodyear Studded Tread Motorcycle Tires, lined with the proper Goodyear Blue Streak inner tubes, as confirmed by a Goodyear histori an in Akron, Ohio. The tire treads still have wisps of flashing between the knobs. Could Shaw have given up on the motorcycle without even wearing down the origi nal tires?

Kennedy believes that this must be the case. The paint on the inside of both fenders is almost perfect, free of chips and dings that would accumulate after just a few hundred miles on the dirt roads around Tomah in 1913.

Kennedy dismantled the Harley to clean and preserve it and discovered that every fastener was original. The decals, including a Harley-Davidson shield on the toolbox, are all intact, as are the rubber pads on the pedals. The only parts missing are the skip-link chain for the pedal drive and the original leather mud flap on the front fender. Someone fash ioned a replacement flap of rubber belting, but attached it with the original bolts. Kennedy says drive chains were often lifted for use on farm machinery of the era. The bike was fitted with a Hawthorne "Old Sol" acetylene headlamp, but the tank is missing.

The leather "Mesinger" saddle, moldy and dirty before conservation, is now so smooth and clean it seems barely broken in. In 1913, Harley gave the "Renault Gray" paint on the tank and fenders an overcoat of varnish, which now glows with a golden patina. One curious point of wear is on the front of the forks, where the paint has been rubbed away to bare metal, perhaps from the luggage rack used to tote mail. Kennedy attributes other scratches on the paint and wear on the ends of the leather handlebar grips to 85 years of being moved around, not to a lot of riding.

A fter being parked for whatever reason, our Model 9B reappears in 1949. Fermin Shaw died on December 26 of that year, a resident of Rolling Hills, the Monroe County poor farm. He's buried there in a grave marked only by a number. He had lived at the county farm on and off since 1944, and his admissions records indicate he had a sister, Mrs. May Temple, living in Oshkosh. City records from 1944 tell us that May was the widow of Earnest Temple, and owned a home that she shared with Howard Temple, who was perhaps her late hus band's brother.

On July 21, 1949, Howard Temple, who by now had married and was not living with May, received a letter from H.E. Hoyt of the Harley-Davidson Service Department. Temple had written to the factory in Milwaukee seek ing information about an old Harley-Davidson. Five months before Fermin Shaw's death, Temple was sniffing around the old 9B. In the letter, Hoyt opens,

"You sure have located an ancient-model Harley-Davidson, and we are surprised to learn that one is still around with the original tires and paint job on it." From the number on the engine case, 7400D, Hoyt identifies the bike as a 1913 Model 9B, provides some specs, and then closes with this assurance: "The old 9B-model Harley-Davidson never did break any speed records, but if it is in good running order as you tell us, we'll bet it could make a couple of transcontinen tal trips today without a miss."

In 1955, Howard Temple wheeled the Harley-Davidson down to the Oshkosh Public Museum and presented it "on loan" with instructions that it was to be released only to him, not to other family members. Could there have been a flap over ownership of the bike? A museum is a good place to store something valuable or interesting you don't want to sell or give away. Just don't forget you left it there. Or die. Which is apparently what happened to Temple, who vanish es from city records by 1957. Last year, unable to find a trace of the owner, the museum legally accessioned the 1913 into its collection.

Silent Gray Fellow was the nickname hung on early singlecylinder Harley-Davidson models like the 9B. Silent because they had a muffler to tone down the exhaust. Gray because it was the standard color. Fellow was an allusion to the reliable companionship the bike would provide its rider. I wonder if this bike fell short of that promise and betrayed Fermin Shaw. Perhaps he startled too many cows and horses with the machine, or had a scare and swore off the mechanical mount. It could be that the roads were just too rough or too often muddy or frozen to make travel on a motorbike practical. He could have been seduced by Henry Ford's Model T.

The answers to those questions have been lost to history. Thanks to serendipity anda strong dose of good luck, the Model 9B has not.