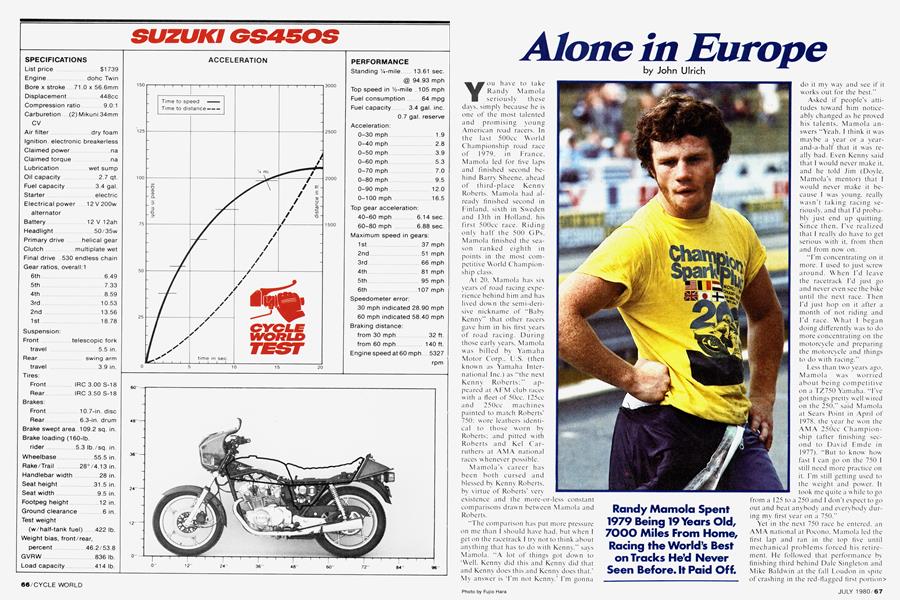

Alone in Europe

John Ulrich

You have to take Randy Mamola seriously these days, simply because he is one of the most talented and promising young American road racers. In the last 500cc World Championship road race of 1979, in France.

Mamola led for five laps and finished second behind Barry Sheene, ahead of third-place Kenny Roberts. Mamola had already finished second in Finland, sixth in Sweden and 13th in Holland, his first 500cc race. Riding only half the 500 GPs.

Mamola finished the season ranked eighth in points in the most competitive World Championship class.

At 20. Mamola has six years of road racing experience behind him and has lived down the semi-derisive nickname of “Baby Kenny” that other racers gave him in his first years of road racing. During those early years. Mamola was billed by Yamaha Motor Corp.. U.S. (then known as Yamaha International Inc.) as “the next Kenny Roberts;” appeared at AFM club races with a fleet of 50cc, 125cc and 250cc machines painted to match Roberts’

750; wore leathers identical to those worn bv Roberts; and pitted with Roberts and Kel Carruthers at AMA national races w henever possible.

Mamola's career has been both cursed and blessed by Kenny Roberts, bv virtue of Roberts' very existence and the more-or-less constant comparisons drawn between Mamola and Roberts.

“The comparison has put more pressure on me than I should have had, but when I get on the racetrack I try not to think about anything that has to do with Kenny,” says Mamola. “A lot of things got down to ‘Well. Kenny did this and Kenny did that and Kenny does this and Kenny does that.’ My answer is ‘I'm not Kenny.' I'm gonna do it my way and see if it works out for the best.” Asked if people’s attitudes toward him noticeably changed as he proved his talents. Mamola answers “Yeah. I think it was maybe a year or a yearand-a-half that it was really bad. Even Kenny said that I would never make it. and he told Jim (Doyle, Mamola's mentor) that I would never make it because I was young, really wasn't taking racing seriously. and that I'd probable just end up quitting. Since then. I’ve realized that I really do have to get serious with it. from then and from now on. Yet in the next 750 race he entered, an AMA national at Pocono, Mamola led the first lap and ran in the top five until mechanical problems forced his retirement. He followed that performance by finishing third behind Dale Singleton and Mike Baldwin at the fall Loudon in spite of crashing in the red-flagged first portion> of the restarted race. With that ride. Mamola beat established racers who were competing in nationals before Mamola even sat on a road racer.

“I'm concentrating on it more. I used to just screw around. W hen I’d leave the racetrack I’d just go and never even see the bike until the next race. Then I'd just hop on it after a month of not riding and I'd race. What I began doing differently was to do more concentrating on the motorcycle and preparing the motorcycle and things to do with racing.”

Less than two years ago. Mamola was worried about being competitive on a TZ750 Yamaha. “I've got things pretty well w ired on the 250.” said Mamola at Sears Point in April of 1978. the year he won the AMA 250cc Championship (after finishing second to David Emde in 1977). “But to know howfast I can go on the 750 I still need more practice on it. I'm still getting used to the weight and power. It took me quite a while to go from a 125 to a 250 and I don't expect to go out and beat anybody and everybody during my first year on a 750.”

“It was just one discouraging breakdown after another all year,” said Mamola afterwards. “I never had a chance to finish a national but had been running in the top 10 at each one. We got to Pocono and I was only a couple of seconds off' Baldwin’s time in the first practice, and all of a sudden I was right in there with Baldwin’s times in the second practice. I got the lead at the start and Baldwin got by me on the back straight, and on the third lap the thing started vibrating really bad, so I figured that I’d back off a little and try to hang onto second. Then Gene Romero and Dale Singleton and Richard Schlachter caught up to me and that put me into fifth. There were still some other riders coming up and I figured that since it was half the race still to go I'd never finish good, so I pulled it in.

“The only difference was that we left out my seat pad. I usually ran with this thick seat pad on the rear of my bike’s seat, just like w hen I first rode a 25Ö and was so little and the pad held me forward so I could reach the handlebars. We just left it off for Pocono, and something happened. I gassed her up and came into the pits after practice and everybody said I was doing really good. Then I said ‘Hey. We didn't have the pad on the seat.' Then I realized that Kenny’s about the same height as me now and Stevie Baker too. and they never had a pad. so we should just leave it off. It’s been working really good ever since. I don't know if that was a trick.’’

Just before qualifying fourth behind Baker. Roberts and Romero at the 1978 Laguna Seca F750 round. Mamola talked about his new-found 750cc success and the future outlook. “I didn’t come out this year to go out and try to beat everybody. It took me aw hile to get used to my 250. but I can just about do anything on my 250 now. except that every once in a while I'll end up laying it down. It just takes me a while, and I accept that. I think that's why I haven't been hurt. When I go out on a new bike or something bigger, like when I went from my 125 to my 250. I always take my time. I never try to stay with anybody. I never follow anybody, but I just do it on my ow n and progressively build up faster and faster. That's what I planned on doing this year on my 750. and so I figured I really didn't have a chance to beat all those guys.

I really didn't care. It was my first year on a 750 and I told everyone involved in mv racing program ‘Don't go expecting miracles out of me. because I’m not going to do it. I'm not going to get hurt.’ So far. everything’s working good.’’

Mamola proceeded to go out in qualifving sessions behind first Roberts, then Baker, each time taking several seconds oft' his lap times. He explained what he was doing later.

“I can sit at a corner and watch Kennv go through the corner, just watch and concentrate on where he’s sitting on the bike, where his knee is at, where his feet are; then I can get on my bike and can feel like my body changes and I can feel—just for a split second—just like Kenny going around the same corner. It’s almost like I am Kenny for a split second.

“I learn really quickly. In (timed) practice. Kenny pulled away from me but I could see him in so many corners, where he sat and what he was doing and that’s what happens, and I picked up like a second and a half. Just by watching him do it. It’s natural to me, but it’s weird. I do the same thing I see him do and things work out. It’s strange.”

It may be strange, but it worked. Mamola started 1979 by running with the leaders at Daytona, turning at least one lap in the 2:05 range and leading once across the finish line before his TZ750's gearbox failed on the 11th lap. He then went to England for the Anglo-American Match Races, and scored 67 points, second only to Mike Baldwin, and ahead of former World Champion Barry Sheene and experienced American 750 pilots David Aldana, Gene Romero. Richard Schlachter. F750 World Champion Steve Baker, Wes Cooley, Daytona winner Dale Singleton and John Long.

Most of the Americans headed for home after the Match Races, but Mamola, then 19 years old, stayed in Europe for his first season of Continental competition, riding a 250 backed by a group of Italian firms, including Bimota frames. Adriatica Industries and MDS Helmets. Adriatica was developing an inline, rotarv-valved Twin similar to the successful Kawasaki KR250. It hadn't been ready in time for the start of the year's racing at Daytona, so a Yamaha TZ250 engine was prepared bv Mamola's tuner. George Vukmonovich.

Mamola's Italian connection was put together by his discoverer, sponsor, manager and promoter. Jim Doyle. A Pan Am 747 pilot by trade. Doyle is a super enthusiast and ex-racer, the man generally given credit with bringing Kenny Roberts to the attention of Yamaha early in Roberts’ career. With Roberts firmly contracted to Yamaha and on top in his racing, Doyle turned his attention to Mamola, providing him with bikes and support as early as 1975. when Mamola was just 15 years old. With Dovle as his guide. Mamola progressed through American AFM and AMA racing from a little, determined kid on very fast bikes who cried when he lost, to a serious threat on any type and kind of machinery.

At Daytona 1979. Mamola battled with Skip Aksland and Freddie Spencer for the 250cc lead until his bike's front brake pads wore out from Mamola's deep runs into the corners. He finished third.

Then, the 250cc GP circuit. In Venezuela, fifth. Germany, second behind reigning World Champion Kork Ballington. Italy, second again behind Ballington's factory Kawasaki, a remarkable showing for a youngster on a non-factory effort.

But as well as Mamola rode, serious problems confronted his relationship w ith the Bimota/Adriatica/MDS group. Vukmonovich worked on the bike, still Yamaha-engined. but wasn’t allowed to install larger front brakes. Mamola kept burning up the brake pads during races, and no amount of complaining would convince the Italians that the small, light brakes (made in Italy) were at fault. The backers just weren't used to anybody using brakes like Mamola did.

Worse. Doyle learned that the MDS helmet didn't pass Snell 75 certification, a fact which worried Mamola. Finally, the group wanted to place more emphasis on testing the Adriatica engine and wasn’t worried about missing a few Grands Prix. Since Mamola's goal was the 250cc World Championship, that was a serious rift.

The problem went deeper than the mechanical and organizational. Mamola learned after Imola that his father. Ed. was to undergo surgery back in Santa Clara, and wanted to fly home to visit him on a free weekend. The Italian group insisted that Mamola stay in Europe and test, and the program fell apart.

Mamola’s riding hadn’t gone unnoticed and he attracted backing from Belgian importer Serge Zago. who loaned a stock Yamaha TZ250 for the rest of the series. Mamola entered the stock TZ in the next GP, Spain, and finished eighth. He crashed in practice on the same stocker in Yugoslavia, then finished 10th in the GP with huge scabs on one foot and hand from the crash.

The scene is Assen. Holland. June 1979. Zago's TZ250 is obviously down on power. Randy has also been provided with a Zago-sponsored Suzuki RG500. He's never ridden one before. He’s never seen the track before. Weather conditions change continuously, from warm and sunny to cold with rain, so Mamola must sort out the 250. learn to ride the 500 and figure out the track, all at once. It is not going well.

“You think I want to be here?” Mamola asks an American reporter in the pits. “I don't want to be here. I talk to people back home and they think this is some kind of vacation. It’s miserable.

“Like the Bimota thing. I had just had it. Everything I wanted they said no. I wanted to go home and visit my father. They said no. I wanted good brakes. They said no. the brakes are already good. I’d argue with George. I was just taking too much B.S., too much pressure. I thought about quitting and going home for good, but I thought that if I went home right away my parents would throw me out of the house because I'd argue with them all the time. George and I were living in an apartment in Italy and there w-as nothing to do. George would go to work on the bike and I'd just sit there. There was nothing to do. Thev wanted me there in case we had to test, but once I got there, we never did any testing. I just sat there. It really gets bad when you have to sit there for two or three weeks. Between races there is nothing to do. There's no TV you can understand. There is U.S. Armed Forces Radio, and I listen to that a lot. Right now it's not so bad because I stay with my new' sponsor. Serge Zago and his family. It’s just like my home. If I want to get something out of the refrigerator I can just go and take it. It’s a lot better.”

continued on page 80

continued from page 69

Mamola pauses and looks at the sky. “This is nice now but it could rain any time. In Austria it snowed and you had to practice in it. When you came into the pits and got off the bike your hands hurt so much it felt like you put your hand on the pavement and somebody stomped on it with a big boot. Then on race day it was clear and hot. In Germany it rained the first practice and was dry for the next. You’re trying to learn the track and conditions change all the time.”

The obvious question is why Mamola is in Europe. He answers instantly, with the assurance of someone who is certain.

“More races. In the U.S. there are five races. I can ride once a month. How can I get any better? Here I can race once a week from now until October. Good money and good experience. Plus back home how many guys are going for the lead in an AMA race? Three guys. Like me. Freddie and Skip going for it at Daytona. Here it’s that plus another six guys going for it. You don’t have to only worry about one guy. like say Kenny in an AMA 750 race, but so many other guys who can beat you. The competition is that much stiffer. Any one of seven or eight guys could beat you.”

Trevor Tilbury, one of Roberts’ mechanics, walks up to Mamola. “What’s it like to get on a 500?” he asks.

“It’s okay,” says Mamola. “Nothing spectacular. Kind of hard to get used to. This is a hard place to get used to it. It’s hard enough on a 250. If you make a mistake.on a 500 . . .” Mamola gestures toward one of the scenic canals lining much of the circuit.

“It’s altogether different from a 750,” Mamola continues. It feels different, handles different. It’s very different. Plus I haven't ridden a bike with two shocks in a long time. I just have to get used to it and this isn't the place to get used to it.

“I'd like to finish in the top 10 here,” says Mamola, “in my first 500 GP. But it would be better for me to finish top 15 or top 20 and finish rather than try to get top 10 and throw it away. I don’t see anything against trying harder, but I don’t see getting hurt trying to do better than you can do.

“But there’s no way I'm going to get on a 500 and go as fast as Kenny or Barry. You know how many years Barry’s been riding a 500? I've only got three-and-a-half years experience riding a big bike and it was always breaking down. I’m only 19. I’ve got plenty of years left to come back to Europe.”

His pragmatic viewpoint didn’t keep Mamola from taking the continent by> storm, improving his finishes every race. At Assen on the 250 he was 7th. He didn't finish on the 250 at Sweden, due to a transmission failure, and crashed in the rain in Finland, destroying the bike. But Mamola was second in Great Britain, fifth in Czechoslovakia at a dangerous track he hated, and fourth in France. His 250 season points left him fourth in world championship standings.

Amazingly, Mamola had more spectacular results with the 500, from 131h at Assen to sixth in Sweden and second in Finland, his third 500 GP. By the British round Mamola’s confidence was way up and his old 250cc problem of wearing out brake pads halfway through the race showed up on the RG500 he didn't finish.

But at the last 500cc GP of the season, in France, Mamola led for five laps and finished second behind Barry Sheene, ahead of third-place Kenny Roberts.

Toward the end of 1979, it looked like Mamola would be a casualty in the F.I.M. Grand Prix vs. World Series war. Offered a factory ride by Yamaha if he would agree to enter Grands Prix, Mamola refused, bound by honor and contract to the fledgling World Series. The decision was agonizing: Mamola was turning his back on factory backing and big money.

The situation worsened w hen World Series faltered— firebrand Kenny Roberts said it wasjust put into a holding pattern — and the riders aligned with World Series regrouped for another season of Grands Prix. That left Mamola without a GP ride and without the money guaranteed to World Series riders as well. For a 19-yearold who left his home in California for a year to make his name and fortune in European road racing, it seemed the worst of all worlds.

Obviously,Mamola had sufficiently impressed Yamaha to be offered a factory ride. And fortunately, the story has a happy ending: After World Series ran aground. Suzuki G.B. (the British Suzuki distributor), offered Mamola a factorybacked ride for 500 Grands Prix, complete with works bikes and a lucrative contract. Mamola accepted, and returns to Europe in 1980 with full support for an assault on the title.

Mamola, now' 20, went to Europe in 1979 with the intention of winning the 250cc World Championship and making his name in Grand Prix. He didn't get that championship, but gained the experience, honed his abilities and landed the backing he needs to seriously contest the 500cc World Championship in 1980. Kenny Roberts is firmly in control of the title now', having won in 1978 and 1979. But this year the greatest threat to Roberts' crown may come not from one of the established Europeans, but from Randy Mamola. Œ