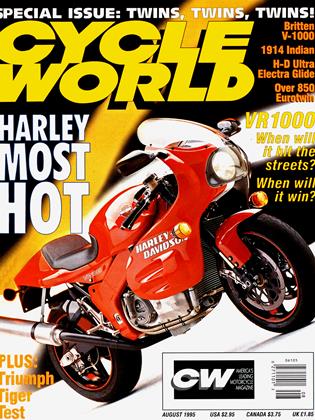

Good company

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

LET’S FACE IT: MOTORCYCLING DOES NOT have a tremendous number of historically famous persons to call its own.

I don’t mean legendary insiders, such as motorcycle racers. We’ve got plenty of those. I’m thinking more of people who are world famous for accomplishments outside the motorcycle world—writers, statesmen, etc.

Aviation seems to have attracted the lion’s share of colorful and literate public figures in this century. The romance of flying has been pretty well documented by such luminaries as Cecil Lewis, Saint-Exupery, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Richard Hillary, Richard Bach, Ernest K. Gann, Roald Dahl, Beryle Markham and many others.

Car enthusiasm, too, has produced many famous exponents, though they are distributed through such a wide range of general interest (touring, rallying, racing, collecting) that the focus is rather watered down. You have to concentrate mostly on the higher levels of racing to find evidence of passion and philosophical speculation. Everybody drives.

But not everybody rides a motorcycle. There’s a finer focus here; thousands are eliminated from the sport by timidity, incompetence or-most oftensimple lack of interest. So those who participate automatically become members of a relatively small club.

Probably the best know historical figure to have been a motorcycle buff is T.E. Lawrence. He had the unfortunate distinction, of course, of being killed on his Brough Superior, but it was not such a bad end to a dashing life.

Though he was also an avid bicyclist and an aviation devotee, Lawrence’s most impassioned descriptions of machinery and the joy of speed are dedicated to motorcycling, mostly in a few great passages from his oft-quoted book, The Mint.

Who else can we think of?

Novelist Thomas McGuane has written a nice essay on motorcycle racing, and poet James Dickey has caught the essence of a lone bike on a country road. Gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson, of course, has written all kinds of lively stuff about bikes (recently right here in CfV, I am pleased to say). My own need to be out on the road was fueled by an early reading of Peter S. Beagle’s fine book, I See by My Outfit.

In terms of wide public appreciation for the aesthetics and pleasures of bike ownership and riding, however, probably nothing has had as much influence as Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. When the book came out, you could almost hear the reading public of America say to itself, “If anyone this smart likes motorcycles, they must be good.”

Besides writers, and the random anomalous capitalist such as Malcolm Forbes, most of motorcycling’s celebrity exponents seem to have come from show biz. We’ve had Clark Gable, Robert Young, Keenan Wynn, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Lee Marvin, Elvis, Bob Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, Duane Allman, Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, the Carradine brothers and many others revealed to the public as riders whose enthusiasm goes beyond the movie screen or the recording studio. And then there’s Steve McQueen. When I was in high school, McQueen made bike ownership seem almost a requirement, like breathing.

Currently, Jay Leno is probably the celebrity best known to the general public as a motorcycle nut. As such, he may have done more good than the Honda 50 to convince the American population that motorcycling is fun and enjoyable (“If Jay likes bikes...”).

Okay, I retract my premise. There are quite a few famous motorcyclists, and we are in good company. Still, we can always use one more.

Which is why I was happy to learn, in a recent reading of Thomas Keneally’s remarkable book, Schindler’s List, that Schindler himself was a motorcyclist.

' Yes, Oskar Schindler, the businessman with a heart, the fellow who brewed up a dangerously clever mixture of camaraderie, daring, intrigue, economics and outright bribery to save his Jewish employees from the Nazi death camps, was one of us.

Not just a motorcyclist, but an enthusiast and hard-core racer. Born to an Austrian family living in Czechoslovakia, he spent his teen years zipping around the Moravian hills on a red Italian 500cc Galloni, which Keneally says was probably the only one in the country.

In 1928, he bought one of only four Moto Guzzi 250 racebikes sold outside Italy and rode the bike to a third-place finish in a mountain roadrace between Brno and Slobeslav, against tough international competition. At the Altvater circuit, he beat the Moto Guzzi, BMW and DKW teams across the finish line, only to be relegated to fourth place over a flagging error on the last lap. A personal triumph nonetheless.

When I finished the book, I set it aside and said to myself, “Well, I should have known.”

It follows a pet theory I have long nurtured that enthusiasm for something real (motorcycles, for instance) is a great displacer of hate, which is imaginary yet has terrible consequences in the real world.

It has been my general observation, as an avid reader of history, that religious and political fanatics are usually people who don’t actually know how to do much. Except maybe fret about the conduct of others.

In other words, they are people in need of a good hobby. They need, more than anything, some passion outside themselves and the dark whirring of their own mental gears.

Schindler was a man who was incapable of organizing a death camp. Or of blowing up a Federal office building. He had better and more important things to do. He loved life.

He was a motorcyclist.

Proud to have him aboard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupSolving the Great Ducati 916 Mystery

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart