LEANINGS

Absolute power

Peter Egan

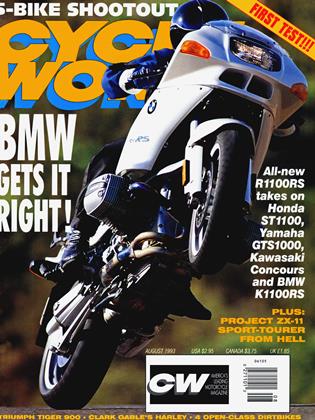

THIS PAST WEEKEND I CONFESSED TO my friend Tom Quatsoe that I have recently become intrigued with the idea of someday owning a Kawasaki ZX-11, partly just for the fun of having a really quick two-up sport-tourer, and partly to cast my vote for any motorcycle that can crank out 132 rearwheel horsepower and a top speed of 176 mph while remaining civilized and ridable around town.

“This is probably a good time to do it,” Tom said. “We might not ever be able to buy a motorcycle that fast and powerful again.”

No? Well, maybe not. Still, I couldn’t help but smile, hearing this familiar old refrain. An echo from the past.

Thirteen years ago, when I first came to work at Cycle World, then-Executive Editor John Ulrich had just bought himself the last of the slide-throttle-carbureted Suzuki GS 1000s. He was leaving it in the crate and storing it away in his garage because motorcycles would probably never be so fast and powerful again, so unfettered by smog controls.

I suppose a case could be made that few performance motorcycles made since have been as versatile and comfortable as that old Suzuki, but there have been many, many bikes made since 1979 that are faster, smog controls or no. John realized very quickly after buying the Suzuki that the horsepower race had not peaked after all, and sold the bike a year or two later.

Now, of course, there is a real threat of future horsepower restrictions. Germany and other European countries have a voluntary 100-horsepower limit on motorcycle engines, partly as a response to the Greens, and partly, I suppose, as a sop to the professionally indignant safety-fixated non-motorcyclist who needs three times that horsepower to make his Mercedes get out of its own way.

This limit has always seemed slightly amusing to me, as there is nothing magical about 100 horsepower, except in the minds of people who don’t understand its arbitrary nature. It is a measurement of work, based on the force required to raise an arbitrary unit of weight an arbitrary distance in an arbitrary amount of time. If horses had been extinct before the Industrial Revolution, it could just as easily have ended up as dogpower, in which case 100 horsepower might equal 479.6 dogpower.

So would there be a public outcry to limit our bikes to 479.6 dogpower? No. I imagine 500 dogpower would become the very image of dreaded excess. We like our numbers tidy, our packages neatly wrapped.

Essentially, what the public does not like is fast bikes, and 100 horsepower has become the bogey, the place in the mind where others begin having too much fun or behaving too dangerously.

Never mind that there has never been any link made between horsepower and motorcycle accidents. In fact, some insurance studies have shown an inverse relationship, probably because young, inexperienced motorcyclists can seldom afford big, powerful bikes. I’ve been riding for 29 years, and the causes of near-accidents have always been the same: Sand on corners, wet leaves, car turning left, following too closely, passing too late. None of my close calls had anything to do with horsepower. I had exactly the same threats to good health on my Honda CB160 as I have now on my Ducati 900SS. More, in fact, because I was less experienced.

In fact, the only danger I see in powerful sportbikes is that the owner of one is more likely to think of himself as Wayne Rainey, when, of course, he’s generally not. And the main danger with the old CB160 was a tendency to think of oneself as Mike Hailwood, who the owner also usually was not. In any case, you could crash just as effectively on 28 horsepower then as on 132 horsepower now. Let’s face it; the source of nearly all accidents is the human brain. Horsepower doesn’t know poor judgment from Shinola. It is indifferent.

Why am I saying all this?

Well, to paraphrase Will Rogers, I never met a horsepower I didn’t like.

Horsepower gets us around trucks right now, livens acceleration in uphill sweepers, allows us to carry a passenger and luggage without diminished elan, tugs (or, better yet, yanks) gratifyingly on the arms when we pass the city limits sign. Horsepower is fun.

And it has not escaped my notice over the years that, within my own small, ever-changing motorcycle stable, I have tended to favor those bikes with power over those that were lacking it. Once I bought my KZ1000, my CB750 Honda went almost unridden. One weekend on a BMW R100RS testbike caused me to trade in my sweet-running but docile R80 for the bigger Boxer. The new generation of more powerful Ducatis quickly seduced me away from my favorite bevel-drive Duck. The new BMW Kl 100RS I rode last week is much nicer than the old K100RS, and people are constantly trading in their 883 Sportsters on 1200s or Big Twins. They almost never, ever, go the other direction.

This is not to say big bikes are better than small bikes; only that a small bike with power is more fun than a small bike without power. I have never seen the riding experience on a motorcycle within any size, weight or utility category diminished by the addition of extra ponies-except in a few screwedup non-factory tuning projects.

The way power is delivered, of course, has a lot to do with its appeal. In any streetbike, I generally prefer immense torque and strong midrange acceleration to a peaky, high-end whoop that blasts out another 20-mph rush just as you are entering the next corner. This is probably why I’ve owned a few more big Twins than cammy inline-Fours over the years.

On the other hand, there’s nothing wrong with immense torque, strong midrange acceleration and high-end whoop. Which the guys at the magazine tell me may be found in abundance with the ZX-11.

Good for Kawasaki. And may the day never come when they have to make the last really powerful bike for collectors to store away in crates. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue