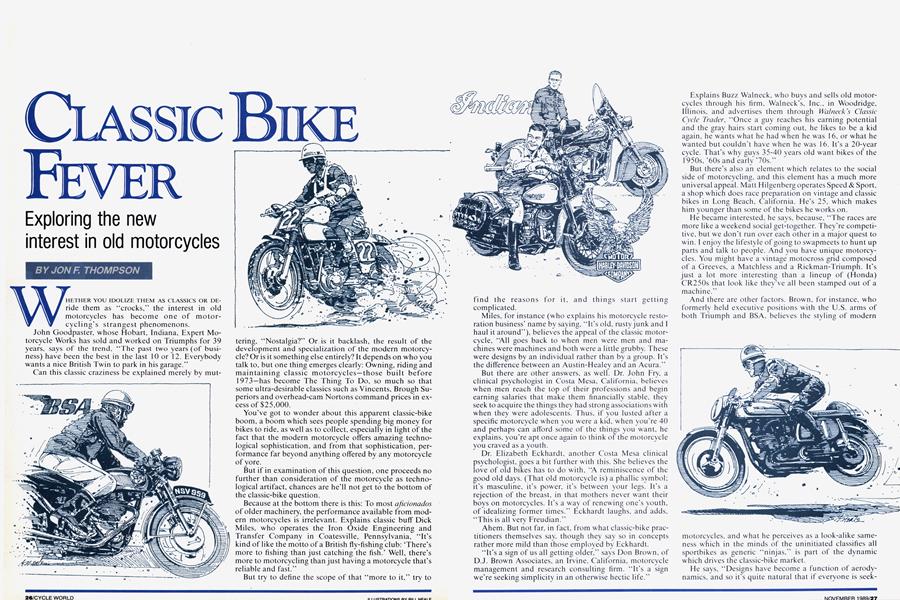

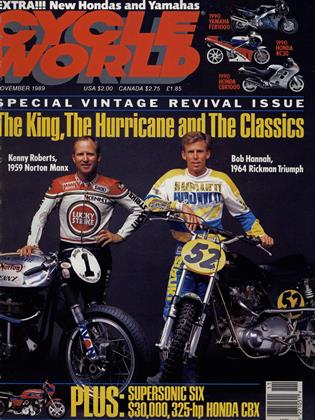

CLASSIC BIKE FEVER

Exploring the new interest in old motorcycles

JON F. THOMPSON

WHETHER YOU IDOLIZE THEM AS CLASSICS OR DEride them as “crocks,” the interest in old motorcycles has become one of motorcycling’s strangest phenomenons.

John Goodpaster, whose Hobart, Indiana, Expert Motorcycle Works has sold and worked on Triumphs for 39 years, says of the trend, “The past two years (of business) have been the best in the last 10 or 12. Everybody wants a nice British Twin to park in his garage.”

Can this classic craziness be explained merely by muttering, “Nostalgia?” Or is it backlash, the result of the development and specialization of the modern motorcycle? Or is it something else entirely? It depends on who you talk to, but one thing emerges clearly: Owning, riding and maintaining classic motorcycles—those built before 1973—has become The Thing To Do, so much so that some ultra-desirable classics such as Vincents, Brough Superiors and overhead-cam Nortons command prices in excess of $25,000.

You’ve got to wonder about this apparent classic-bike boom, a boom which sees people spending big money for bikes to ride, as well as to collect, especially in light of the fact that the modern motorcycle offers amazing technological sophistication, and from that sophistication, performance far beyond anything offered by any motorcycle of yore.

But if in examination of this question, one proceeds no further than consideration of the motorcycle as technological artifact, chances are he’ll not get to the bottom of the classic-bike question.

Because at the bottom there is this: To most aficionados of older machinery, the performance available from modern motorcycles is irrelevant. Explains classic buff Dick Miles, who operates the Iron Oxide Engineering and Transfer Company in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, “It’s kind of like the motto of a British fly-fishing club: ‘There’s more to fishing than just catching the fish.’ Well, there’s more to motorcycling than just having a motorcycle that’s reliable and fast.”

But try to define the scope of that “more to it,” try to find the reasons for it, and things start getting complicated.

Miles, for instance (who explains his motorcycle restoration business’ name by saying, “It’s old, rusty junk and I haul it around”), believes the appeal of the classic motorcycle, “All goes back to when men were men and machines were machines and both were a little grubby. These were designs by an individual rather than by a group. It’s the difference between an Austin-Healey and an Acura.”

But there are other answers, as well. Dr. John Fry, a clinical psychologist in Costa Mesa, California, believes when men reach the top of their professions and begin earning salaries that make them financially stable, they seek to acquire the things they had strong associations with when they were adolescents. Thus, if you lusted after a specific motorcycle when you were a kid, when you're 40 and perhaps can afford some of the things you want, he explains, you’re apt once again to think of the motorcycle you craved as a youth.

Dr. Elizabeth Eckhardt, another Costa Mesa clinical psychologist, goes a bit further with this. She believes the love of old bikes has to do with, “A reminiscence of the good old days. (That old motorcycle is) a phallic symbol; it’s masculine, it’s power, it’s between your legs. It’s a rejection of the breast, in that mothers never want their boys on motorcycles. It’s a way of renewing one’s youth, of idealizing former times.” Eckhardt laughs, and adds, “This is all very Freudian.”

Ahem. But not far, in fact, from what classic-bike practitioners themselves say, though they say so in concepts rather more mild than those employed by Eckhardt.

“It’s a sign of us all getting older,” says Don Brown, of D.J. Brown Associates, an Irvine. California, motorcycle management and research consulting firm. “It’s a sign we're seeking simplicity in an otherwise hectic life.”

Explains Buzz Walneck, who buys and sells old motorcycles through his firm, Walneck’s, Inc., in Woodridge, Illinois, and advertises them through Walneck's Classic Cvcle Trader, “Once a guy reaches his earning potential and the gray hairs start coming out, he likes to be a kid again, he wants what he had when he was 16, or what he wanted but couldn’t have when he was 16. It’s a 20-year cycle. That’s why guys 35-40 years old want bikes of the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s.”

But there’s also an element which relates to the social side of motorcycling, and this element has a much more universal appeal. Matt Hilgenberg operates Speed & Sport, a shop which does race preparation on vintage and classic bikes in Long Beach, California. He’s 25, which makes him younger than some of the bikes he works on.

He became interested, he says, because, “The races are more like a weekend social get-together. They’re competitive, but we don’t run over each other in a major quest to win. I enjoy the lifestyle of going to swapmeets to hunt up parts and talk to people. And you have unique motorcycles. You might have a vintage motocross grid composed of a Greeves, a Matchless and a Rickman-Triumph. It’s just a lot more interesting than a lineup of (Honda) CR250s that look like they’ve all been stamped out of a machine.”

And there are other factors. Brown, for instance, who formerly held executive positions with the U.S. arms of both Triumph and BSA, believes the styling of modern motorcycles, and what he perceives as a look-alike sameness which in the minds of the uninitiated classifies all sportbikes as generic “ninjas,” is part of the dynamic which drives the classic-bike market.

He says, “Designs have become a function of aerodynamics, and so it’s quite natural that if everyone is seeking the same goal in their designs, then ultimately they’ll all meet on the same street corner under the same light with the same things to say. It’s like going into a store and looking at 95 digital watches. They all work well, they all have a similar look.”

Dick Mann, 20 years ago a fierce competitor on the bikes now considered classics and currently a fierce competitor on the vintage motocross scene, puts it even more simply. He says people are buying the old bikes, “For the same reason anyone would buy a walnut table that's 300 years old or stand in line at a museum to look at 1930s furniture. You can see that someone made it, you can see how it works.”

As far as performance is concerned, Mann believes riders get the same feedback, the same thrill, from old bikes as they derive from new ones. He says, “How fast you’re rolling across the ground is irrelevant. You can buy an old bike now for $500 that’ll run well enough to scare you, well enough to put you in jail if they catch you.”

Though the presence of the classic movement is undeniable, its size is indeterminate because the overall size of the classic-bike pool is unknown and because the number of classics that change hands is impossible to chart—some bikes are sold without registration, some are sold and resold again without paperwork ever being formalized by the imprimatur of a state motor vehicle department. Counting club members can be wildly deceptive because many classic-bike enthusiasts belong to a dozen or more clubs. Still, there are enough interested participants that purveyors of classic bikes, those who have soldiered along through the lean years when BSAs could be had free-for-the-hauling-away, have discovered there is profit to be extracted from nostalgia.

Some classic and vintage dealers believe the classic trend has reached its zenith. Says Expert Motorcycle’s Goodpaster, “It’s probably peaked now, it’s gonna level out. It’ll be at a nice plateau for a few years and then, as trends go, someone will come up with some other idea.”

But for the time being, he continues, “The values of these bikes have become pretty well set. When you consider that a 1969 Bonneville in excellent condition goes for $4000 and up—this bike retailed for a third of that when it was new—well, that tells me something. It tells me the older bikes have charismatic value . . . that people want a specific machine, something that looks like a motorcycle.”

Though Miles, of Iron Oxide Engineering, also believes the classic movement may be at its peak, he admits that the movement’s current boom status caught many people by surprise. He notes, “In the last 24 months values have skyrocketed. It’s unbelievable.”

Walneck is also in awe of current prices but thinks the trend will continue, saying of the classic movement, “I just don't see any stopping of it.”

There may, in fact, be no end to the classic-bike phenomenon. It may grow just as the popularity of classic cars has grown, through these general categories of old bikes: veteran bikes of the ’Teens, vintage bikes produced between the wars, today’s post-war classics, and neo-classics such as the Honda CB400F and the Kawasaki Zl-R, two bikes which even now are beginning to incite some collector interest.

What seems important to remember is that the 20-year cycle spoken of by Walneck has proven to be valid, not only in collector motorcycles but in collector cars, which seem a valid barometer to the whole business. Thus, it seems reasonable to expect that if late-1960s bikes are hot now, late-1970s bikes will be hot in 10 years, and late-1980s bikes will be hot in 20 years. That’s a pretty appealing prospect, because it means that all you have to do to own a future classic is wait until the depreciation curve of the bike you’ve always wanted bottoms out. Then you buy, clean it up and wait for a few years. If you’ve played your cards right, you’ll have a valuable classic. If not, well, you’ll still have the bike you always wanted—an interesting, ridable piece of motorcycling’s heritage that will make people smile as they look at it and remember, through the nostalgia it conjures up, The Good Old Days.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1989 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

November 1989 -

Roundup

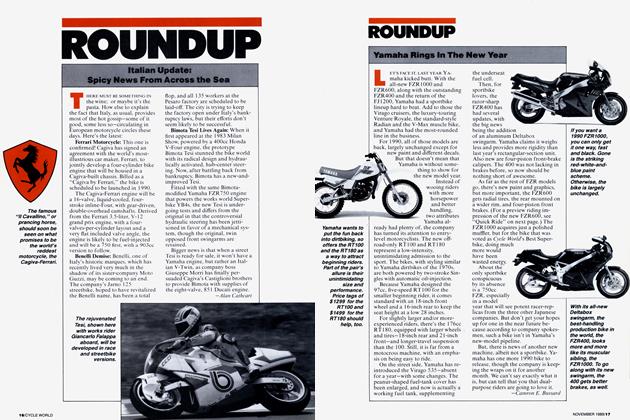

RoundupItalian Update: Spicy News From Across the Sea

November 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

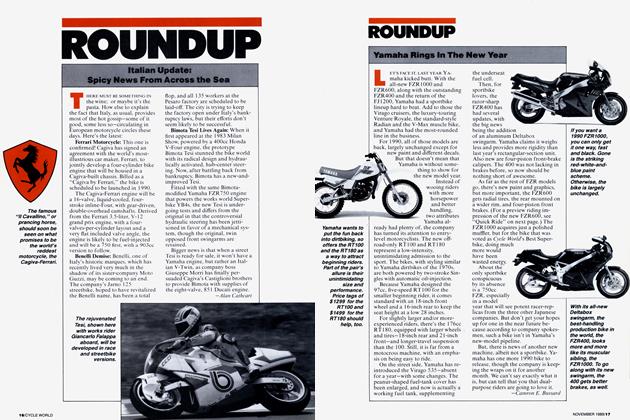

RoundupYamaha Rings In the New Year

November 1989 By Camron E. Bussard