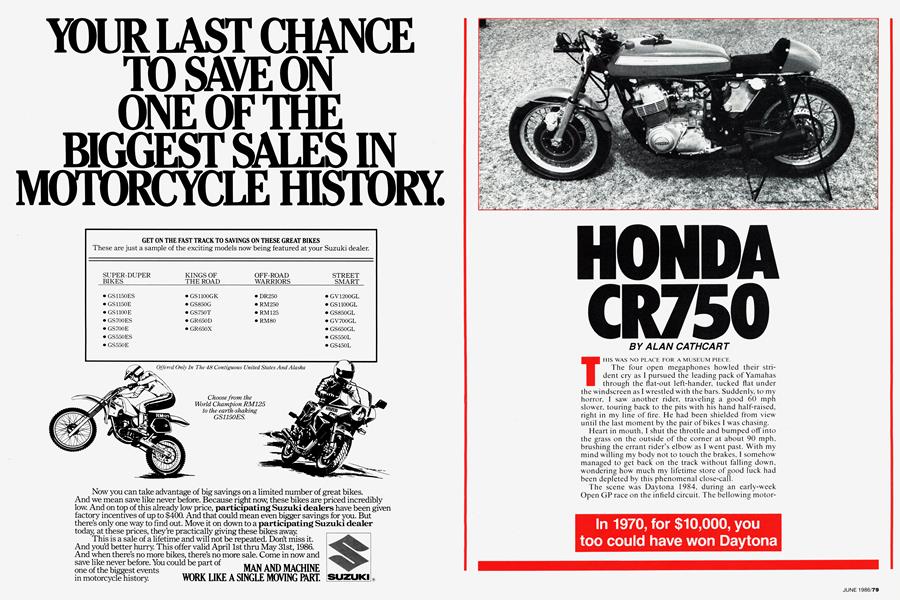

HONDA CR750

In 1970, for $10,000, you too could have won Daytona

ALAN CATHCART

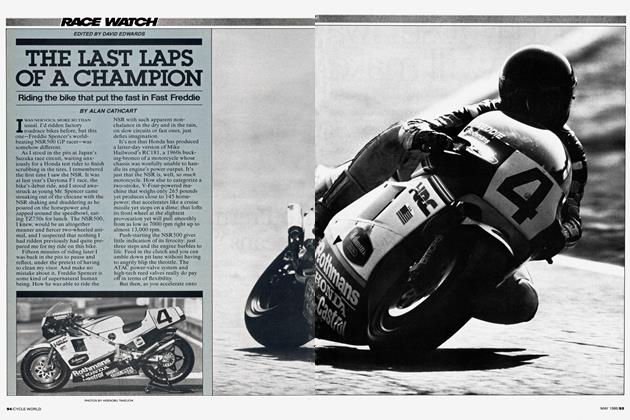

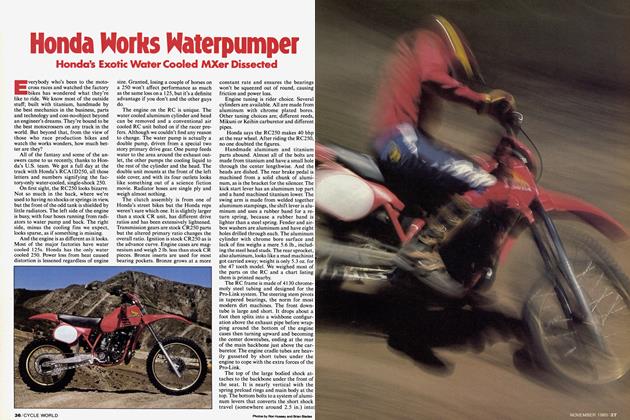

THIS WAS NO PLACE FOR A MUSEUM PIECE. The four open megaphones howled their strident cry as I pursued the leading pack of Yamahas through the flat-out left-hander, tucked flat under the windscreen as I wrestled with the bars. Suddenly, to my horror, I saw another rider, traveling a good 60 mph slower, touring back to the pits with his hand half-raised, right in my line of fire. He had been shielded from view until the last moment by the pair of bikes I was chasing.

Heart in mouth, I shut the throttle and bumped off into the grass on the outside of the corner at about 90 mph, brushing the errant rider’s elbow as I went past. With my mind willing my body not to touch the brakes, I somehow managed to get back on the track without falling down, wondering how much my lifetime store of good luck had been depleted by this phenomenal close-call.

The scene was Daytona 1984, during an early-week Open GP race on the infield circuit. The bellowing motorcycle I almost flat-sided was a 1 969 CR750 Honda, a then1 5-year-old bit of racing history, that went on to carry me to a 12th-place finish against a couple dozen more-modern machines, ranging from near-stock Suzuki Katanas to Yamaha TZ750s. The CR had begun life as a stock, sohc CB750. the four-cylinder road bike that set the motorcycling world on its ear. What separated this bike from most other CB750s, though, is that it had been outfitted with the complete factory race kit, which—in theory, at least—made it identical to the one on which Dick Mann had won the Daytona 200 in 1970.

“It’s the 798th CB750 made,” claims the bike’s current owner, Florida racer John Long. “It went new to a dealer in Dalton, Georgia, who also bought the entire CR race kit for it. Because the kit cost more than $10,000 in those days, he was one of the few who bought one; most people just bought the carbs and cams, and maybe the pipes.”

Reportedly worth 23 added horsepower over the standard CB engine, the race kit consisted of a camshaft with more duration and lift, stronger valve springs, oversize intake valves, smaller exhaust valves, 10.5:1 slipper pistons with just two rings, a close-ratio gearbox, and a battery-less magneto ignition with a fixed advance set at 35 degrees. High-performance chains for the camshaft and primary drive were included, as well, although this didn’t prevent many race-kitted bikes from retiring with broken cam chains.

A set of four carefully tuned open megaphone exhausts, seamed in typical CR Honda style, also was supplied. And while the standard frame was retained, a host of special parts was included in the kit, mostly aimed at reducing weight to around 385 pounds dry. Even so, the CR750 was one of the heavier racers of the early Seventies. But with an output of 90 bhp at 9700 rpm—aided by the kit’s 3lmm Keihin racing carbs—it was also one of the most powerful.

Long saw the bike languishing in the showroom of a Tampa Honda dealer in 1978 as he was driving past. Executing a neat but illegal U-turn, he went back to inquire about its heritage. Considering that as displayed, the CR750 was painted a gaudy tint of pearlescent white, with snake heads and serpents along the fairing. Long must have had X-ray eyes to know what lay beneath. Maybe it was the close-ratio gearbox mounted on a pedestal and encased in glass next to the bike that gave him the clue.

“It looked unbelievably corny,” he remembers, “but I knew instantly what it was. Apparently, some English guy had promised to buy it for $5000, but he hadn’t sent "the money. The shop owner was a drag-race nut, so I got him to trade the CR for a turbocharged CBX. What a deal.” Long also found out about the CR’s competition history. It was first raced at Daytona in 1970, where it dropped out with—you guessed it—a broken cam chain. Rebuilt for Cycle Week 1971, it was ridden to victory in the 100-mile junior race by Dennis Poneleit, who took the lead four laps from the end when a similarly kitted Honda CR retired.

“I remember watching that race,” recalls Long. “The bike looked and sounded great, but it was smoking heavily, especially on the downshift intoTurnOne. They were even lucky to finish; probably had a broken ring or two.”

Hollowing that win, the Honda saw little use, except at the drag strip, where it eventually turned a best time of 10.76 seconds. After Long found it bedecked with boa constrictors and traded for it, he took it back to Miami for a complete rebuild to original specifications. About the only change was to install two-ring Yoshimura cast pistons, instead of the original forged CR slugs. Indeed, the authenticity of the rebuild is such that it stopped Englishman Peter Davill dead in his tracks during a wander through the garages in Daytona. At the time, Davill, a former endurance-racing star, had two CR750s of his own in bits and pieces at home. “It's just the way mine ought to look,” he verified. “They were bloody quick bikes: I once was timed on one of mine at 162 mph.”

Dick Mann's winning CR could only manage 1 52 mph in qualifying for the 1 970 race, still good for fourth fastest. And because my Open GP race did not go up onto Daytona's famed, 31-degree banking, the speed I turned on the bike 14 years later was considerably slower. Besides, just starting the bike proved to be a problem for me. Even after copiously (and properly) flooding the Keihins, and with three people pushing, the Honda refused to light. Ten more minutes of effort resulted in a lot of spluttering and popping, accompanied by some choice language, but no action. Then, Tom Laulds, custodian of one of the famed Honda 250 Sixes and himself a CR750 owner, took over; 30 seconds later, there was a blast of sound as she fired up.

And what a sound. Deep, rich and righteously loud, just the way a works Honda should be.

After making sure the six-gallon alloy fuel tank had the neccessary juice, I was ready for action. The riding position, thanks to the stretched-out, 58-inch wheelbase, felt really comfortable, with the big tank nestling under my chest and providing grip for my elbows. Less reassuring were the cast-alloy clip-ons: original, maybe, hen’s-teeth rare, even, but I wondered what point in their fatigue cycle they had reached by then.

Another pitfall of racing old bikes became much too apparent as I tried to make my way up from a clutchsaving, last-place start by outbraking my opponents into Turn One. Long’s pre-race warning to “watch out for the front brakes” was driven home as I furiously pumped the lever and tried to get the blasted bike stopped. It seems Honda’s dubious combination of stainless-steel discs and flexy hydraulic lines was never intended for the rigors of short-circuit racing. Fortunately, the CR kit also included a fabulous rear drum brake, a masterpiece of magnesium casting that worked superbly and got me out of trouble more than once in the race.

Other than braking, riding the CR750 proved to be simply a matter of lugging the heavy motorcycle through the corners and powering down the straightaways. There is a patch of “megaphonitis” between 5500 and 6000 rpm, so it's best to keep the revs above that mark, although that’s not so easy in tight corners. Everywhere else, though, the tightly spaced gearbox allowed me to keep the engine well on the boil.

A couple of controllable slides out of corners made me less than enchanted with the hard-compound PZ2 Michelins on the bike. But, then, they were almost certainly no harder than the tires Goodyear would have fitted for use on the banking in 1970. To ride this bike really hard, you would have to like powersliding out of turns and have tough, calloused hands that could put up with that kind of abuse.

In retrospective, then, the CR750 seems almost tailormade for Dick Mann and his years of throwing bikes sideways on the dirt-track circuit. But for lesser mortals, the thrill of unleashing the CR's marvelous exhaust howl is enough. And I, for one, am glad that John Long occasionally dusts off his piece of racing history and heads for a racetrack to let the thing echo.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue