LeGrand Jordan and the Impossible Dream

Allan Girdler

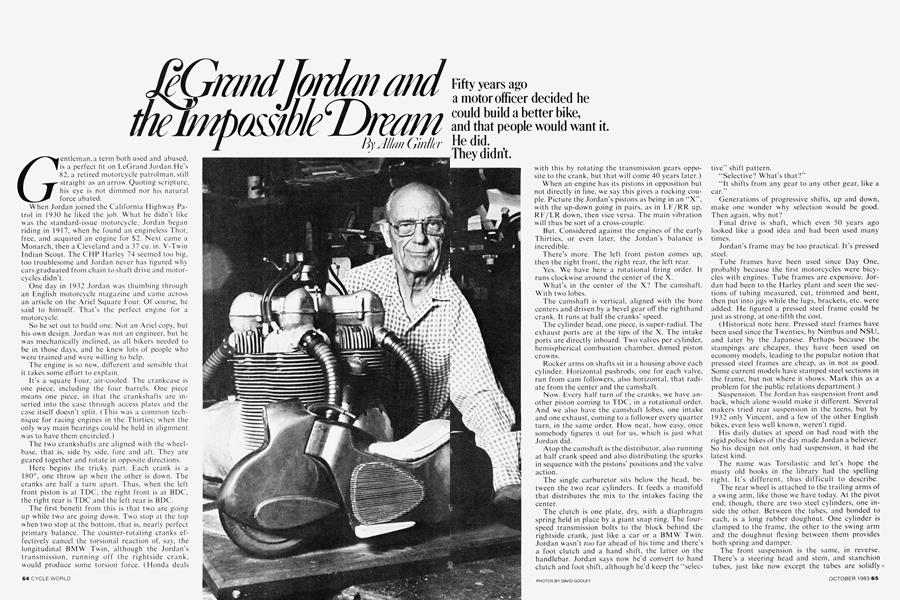

Gentleman, a term both used and abused, is a perfect fit on LeGrand Jordan. He's 82, a retired motorcycle patrolman, still straight as an arrow. Quoting scripture, his eye is not dimmed nor his natural force abated. When Jordan joined the California Highway Patrol in 1930 he liked the job. What he didn't like was the standard-issue motorcycle. Jordan began riding in 1917, when he found an engineless Thor, free, and acquired an engine for $2. Next came a Monarch, then a Cleveland and a 37 cu. in. V-Twin Indian Scout. The CHP Harley 74 seemed too big, too troublesome and Jordan never has figured why cars graduated from chain to shaft drive and motorcycles didn’t.

One day in 1932 Jordan was thumbing through an English motorcycle magazine and came across an article on the Ariel Square Lour. Of course, he said to himself. That's the perfect engine for a motorcycle.

So he set out to build one. Not an Ariel copy, but his own design. Jordan was not an engineer, but he was mechanically inclined, as all bikers needed to be in those days, and he knew lots of people who were trained and were willing to help.

The engine is so new, different and sensible that it takes some effort to explain.

It’s a square Tour, air-cooled. The crankcase is one piece, including the four barrels. One piece means one piece, in that the crankshafts are inserted into the case through access plates and the case itself doesn't split. (This was a common technique for racing engines in the Thirties; when the only way main bearings could be held in alignment was to have them encircled.)

The two crankshafts are aligned with the wheelbase, that is, side by side, fore and aft. They are geared together and rotate in opposite directions.

Here begins the tricky part. Each crank is a 180°, one throw up when the other is down. The cranks are half a turn apart. Thus, when the left front piston is at TDC, the right front is at BDC, the right rear is TDC and the left rear is BDC.

The first benefit from this is that two are going up while two are going down. Two stop at the top when two stop at the bottom, that is, nearly perfect primary balance. The counter-rotating cranks effectively cancel the torsional reaction of, say, the longitudinal BMW Twin, although the Jordan's transmission, running off the rightside crank, would produce some torsion force. (Honda deals with this by rotating the transmission gears opposite to the crank, but that will come 40 years later.)

Fifty years ago a motor officer decided he could build a better bike, and that people would want it. He did. They didn’t.

When an engine has its pistons in opposition but not directly in line, we say this gives a rocking couple. Picture the Jordan's pistons as being in an “X”, with the up-down going in pairs, as in LF/RR up, RF/LR down, then vice versa. The main vibration will thus be sort of a cross-couple.

But. Considered against the engines of the early Thirties, or even later, the Jordan’s balance is incredible.

There's more. The left front piston comes up, then the right front, the right rear, the left rear.

Yes. We have here a rotational firing order. It runs clockwise around the center of the X.

What’s in the center of the X? The camshaft. With two lobes.

The camshaft is vertical, aligned with the bore centers and driven by a bevel gear off the righthand crank. It runs at half the cranks' speed.

The cylinder head, one piece, is super-radial. The exhaust ports are at the tips of the X. The intake ports are directly inboard. Two valves per cylinder, hemispherical combustion chamber, domed piston crowns.

Rocker arms on shafts sit in a housing above each cylinder. Horizontal pushrods, one for each valve, run from cam followers, also horizontal, that radiate from the center and the camshaft.

Now. Every half turn of the cranks, we have another piston coming to TDC, in a rotational order. And we also have the camshaft lobes, one intake and one exhaust, coming to a follower every quarter turn, in the same order. How neat, how easy, once somebody figures it out for us, which is just what Jordan did.

Atop the camshaft is the distributor, also running at half crank speed and also distributing the sparks in sequence with the pistons’ positions and the valve action.

The single carburetor sits below the head, between the two rear cylinders. It feeds a manifold that distributes the mix to the intakes facing the center.

The clutch is one plate, dry, with a diaphragm spring held in place by a giant snap ring. The fourspeed transmission bolts to the block behind the rightside crank, just like a car or a BMW Twin. Jordan wasn’t too far ahead of his time and there's a foot clutch and a hand shift, the latter on the handlebar. Jordan says now he'd convert to hand clutch and foot shift, although he’d keep the “selective” shift pattern.

“Selective? What’s that?”

“It shifts from any gear to any other gear, like a car.”

Generations of progressive shifts, up and down, make one wonder why selection would be good. Then again, why not?

Final drive is shaft, which even 50 years ago looked like a good idea and had been used many times.

Jordan’s frame may be too practical. It’s pressed steel.

Tube frames have been used since Day One, probably because the first motorcycles were bicycles with engines. Tube frames are expensive. Jordan had been to the Harley plant and seen the sections of tubing measured, cut, trimmed and bent, then put into jigs while the lugs, brackets, etc. were added. He figured a pressed steel frame could be just as strong, at one-fifth the cost.

(Historical note here. Pressed steel frames have been used since the Twenties, by Nimbus and NSU, and later by the Japanese. Perhaps because the stampings are cheaper, they have been used on economy models, leading to the popular notion that pressed steel frames are cheap, as in not as good. Some current models have stamped steel sections in the frame, but not where it shows. Mark this as a problem for the public relations department.)

Suspension. The Jordan has suspension front and back, which alone would make it different. Several makers tried rear suspension in the teens, but by 1932 only Vincent, and a few of the other English bikes, even less well known, weren’t rigid.

His daily duties at speed on bad road with the rigid police bikes of the day made Jordan a believer. So his design not only had suspension, it had the latest kind.

The name was Torsilastic and let's hope the musty old books in the library had the spelling right. It’s different, thus difficult to describe.

The rear wheel is attached to the trailing arms of a swing arm, like those we have today. At the pivot end, though, there are two steel cylinders, one inside the other. Between the tubes, and bonded to each, is a long rubber doughnut. One cylinder is clamped to the frame, the other to the swing arm and the doughnut flexing between them provides both spring and damper.

The front suspension is the same, in reverse. There's a steering head and stem, and stanchion tubes, just like now except the tubes are solidly> mounted and run straight down to about the top of the tire, then angle back until they’re directly behind the front hub. Between the tubes and the hub is another swing arm, leading instead of trailing.

The Torsilastic doughnut bonded to the inner and outer cylinders attached to the stanchion tubes and the swing arm are the same, except smaller, as in the rear. Wheel travel is about 3 in., not enough today but radical back then.

Brakes are the best of their time, aircraft. Another distinct difference here. There's a center drum, around which goes a bladder, sort of like a very small, very thick inner tube. Outboard of this bladder, pivoted from a backing plate, are segmented brake shoes, seven in all. Outboard of them is the actual brake drum. When the brake is applied hydraulic fluid expands the bladder which moves the shoes against the drum. Lots of little shoes make closer, more complete contact with the drum and thus use all the drum's surface, which the two conventional shoes of conventional drum brakes never quite do. Disc brakes work better still but they didn't come until airplanes got heavier and faster in the late 1940s.

The Jordan’s styling doesn't need to be described, but it does deserve an explanation.

The Jordan (obviously) is an enclosed motorcycle. For 70 years people have been enclosing bikes to protect the rider from grit, mud, water and wind, and for 70 years other people have been refusing to buy the idea.

This may change through the influence of enclosed bikes like the Yamaha Venture, Honda Interceptor and the various turbos, but that’s in the future.

In the past, enclosed motorcycles were the coming thing, so Jordan used a full body, done by his brother. It looks unusual today, but that’s because style changes. At the time the Art Deco look was how artists did it and the Jordan looks like something that would have resulted if the stylists who did, say, the Indian Chief had gotten together with the stylists for the enclosed Vincent Black Knight. It also bears an uncanny resemblance to the more recent motorcycle project done by Porsche Design but that’s probably more a comment on Porsche Design than the Jordan.

More to the point, Jordan learned in the Thirties what the racers discovered from the full enclosures of the Fifties, namely solid sides and covered or solid wheels make for instant reactions to side winds. Now, Jordan says, he’d leave some places for the winds to go.

Style aside, the Jordan’s body does useful things. The two-person seat hinges up for access to the air cleaner, distributor and batteries. There were two, because the electric starting didn’t work as well as the outside expert engineer said it would. Jordan was firm on the need for electric starting; no man who’s executed 53 kicks without getting the engine to run ever feels quite the same about the purity and efficiency of the kick-start motorcycle.

The prototype weighs—note the present tense 450 lb. The engine displaces lOOOcc, or 61 cu. in. as they said then. There was no emphasis on power, so adequate, as Rolls Royce puts it, is the only rating. Jordan applied for and was granted some patents on the drive train and valve system.

Now. If there is a moral for all this, it must be that what seems to be the hard part, wasn’t. Any bike nut who’s ever done any maintenance knows he couldn’t come close to designing and building his own motorcycle, never mind one that incorporated things production bikes of the day didn’t have.

But here was LeGrand Jordan, a highway patrolman, no credentials, no investment capital, nothing but faith and energy, and he did it.

That was the easy part.

The hard part was money. There was no way Jordan could manufacture his motorcycle himself. Nor, this being the Depression, was there any hope he could raise the money himself. He needed to find a motorcycle company that would use his design, or some related company that wanted to be in the motorcycle business.

Jordan knew a member of Harley’s board of directors, a man who was frank enough to say, sure, there were lots of things wrong with Harleys. The factory knew what they were. But they didn’t plan to fix them or to build newer and better machines because they already dominated the market.

Indian? By this time Indian was in financial trouble, and they already had a Four, albeit an inline that was out of date. Jordan wrote them some letters, never got a reply and wasn’t terribly surprised.

In the U.S. there were two motorcycle companies and they had almost no market at all. Police departments, a hardcore handful of diehard bikers, and that was it.

Not a good time to be in, or get into, the motorcycle business. Armed with patents and plans and belief in his ideas, Jordan criss-crossed the country on his BMW. He visited car companies, steel companies, any firm with manufacturing capabilities and the remotest link to wheeled vehicles.

“Some could say no in a few pages, and some could say no in two lines, but they all said no.”

Or they were at cross purposes. Nowadays it’s fashionable to heap abuse on the car companies for not making small cars. What we forget is the score of people who did make small cars and paid accordingly.

Jordan heard that Powell Crosley, who made two-cylinder small cars that didn’t sell before making four-cylinder small cars ditto, was interested in motorcycles.

They met and had what diplomats call an exchange of views. Crosley did have plans for a motorcycle. But what he wanted was some use for his warehouses full of unused two-cylinder engines. Jordan of course had different plans, and that was that.

The approach of war gave renewed hope, and put the Jordan Four as close as it’s come to production.

Studebaker had been near collapse until the arrival of Paul Hoffman, who would later do great things for the war effort. Hoffman broadened and diversified Studebaker’s product line and he knew the military had interest in motorcycles.

Jordan wrote to Studebaker and Hoffman sent a cordial reply. Jordan went for a visit, the men talked for most of the day and at the end of the session, plans and drawings had been assigned to the Studebaker engineering staff.

That was in July, 1941. Before anything got off the drawing board, it was December, 1941. There was no time to experiment. The military contracts went to the established factories. Studebaker did other war work, then ventured into different styling after the war, then produced compact cars and finally the semi-custom Avanti, which Jordan believes was a substitute for going into the motorcycle business: “If they’d built the Jordan instead of the Avanti, they’d be the leader today.”

Arguable, but understandable under the circumstances. We are compressing decades into a few words, but Jordan bought a secondhand school bus and toured, with his bike in the back, displaying and demonstrating to anybody who might be willing to make motorcycles.

Nobody was. Then Honda and the others arrived and created a market far bigger than anybody dreamed. In time and in turn, Jordan approached them.

And got nowhere, for valid reasons. The Japanese didn’t invent Not Invented Here, but they practice it; companies with hundreds of engineers on the payroll don’t enjoy paying for ideas from outside. Nor can any large corporation forget that scores of lawsuits claiming infringement and/or theft are filed every year.

So Jordan was told that Square Fours are inherently rough, that market research shows motorcycle engines must have a carburetor for each cylinder and his engine only has one. He was told he’d have to sign forms releasing the company from any liability if they looked at his ideas. He signed, and never heard from that factory again. And there were some queries that never got answered at all.

There the matter rests. Jordan maintains an active correspondence file, packed with letters from engineers endorsing his ideas. The pictures here are misleading in that they show an engine on the bench and the motorcycle with an engine. They were taken at different times. There is only one engine. Jordan could pay for the patterns and to have one block cast. (The mold wasn’t quite filled when the block was cast. Some of the fins aren’t quite filled out. The foundry offered to do it again, but Jordan declined. Now he wishes he hadn’t.)

Jordan describes his project in the present tense, as in the changes that would have to be made if production began tomorrow. At the same time, or in the next sentence, he’ll say that he took the engine from the display bench and put it back in the chassis because he won’t be here forever and he’d like to see the bike go to a museum, so he’s made it easy for the museum staff to know where everything goes.

Speaking realistically, the Jordan Four isn’t going to be produced. Progress has caught up with the radical suspension and brakes and bodywork. The engine’s concept is still interesting, and probably workable—water-cooling could be added easily but the world surely has all the Fours it needs.

Speaking emotionally, it’s worth noting that Jordan is not a bitter man. He has a devoted wife, children and grandchildren. He grows fruit trees in his back yard, rides and tinkers with his BMW. LeGrand Jordan worked for 50 years on his better motorcycle, but he never let it interfere with his life.

He told his story with some reluctance. Just as the manufacturers didn’t want to know, so are there people who will borrow the work of others. Jordan is willing to show the bike now, he says, because “It doesn’t matter to me.”

But of course it really does. s

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontKnow Thy Beast

October 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1983 -

Departments

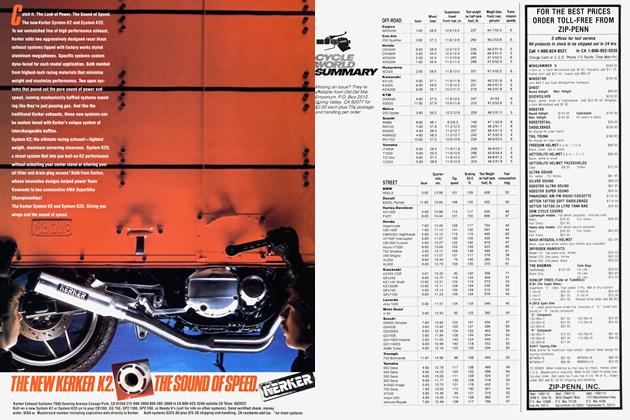

DepartmentsSummary

October 1983 -

Roundup

RoundupDucati Quits Bike Business To Build Engines For Cagiva

October 1983 -

Roundup

RoundupCalifornia Postpones Bike Catalytic Converters

October 1983 -

Roundup

RoundupFeds Give Nod To Barstow-To-Vegas Race

October 1983