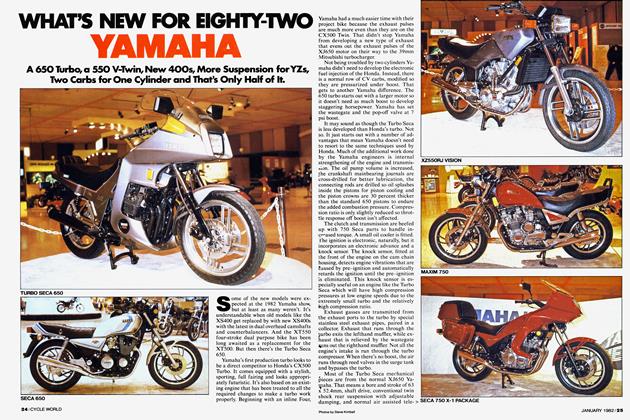

SECOND COMING

Japan’s collectible classics: It’s déjà vu all over again

JON F. THOMPSON

NEVER MIND THAT THE BRITish-bike-collecting craze has peaked. If you've still got a yen for an old bike, you'll be glad to learn that suddenly it's cool — and yes, sometimes profitable—to ride and collect vintage Japanese motorcycles.

Why does anyone care about old bikes? No matter who’s asked, the story is basically the same: We reach a point in our lives that brings with it a shift of the psychic gears. There's a taking of stock, a consideration of goals missed and attained, and of things left too-long undone. And if we're motorcyclists, especially if we've dropped out of the sport to raise families and pursue careers, we begin thinking of the bikes that first caught our attention, the ones that helped form a lifetime's affection for motorcycling.

For many of us. that means the array of Japanese imports that first began trickling into the U.S. during the 1950s, and which hit full stride when Honda, followed closely by its competitors, opened the American branch of its business in 1959. When that happened, it was as though the gates of a dam were opened. That dam was, of course, Japan's incredible manufacturing capability, and out of it flowed motorcycles like no one had ever seen before, motorcycles—like the 10 you see here, which are the bikes collectors agree are the most desirable Japanese vintage bikes—designed specifically for an untapped U.S. market.

1967 Bridgestone 350GTR

Fast, smooth, comfortable and reliable, these top-of-the-line bikes came and went as Bridgestone first got into the motorcycle biz, and then opted to stick with the slightly less competitive, much more reliable tire business. Tough to find parts, but worth the effort, especially if you want something just a little different from the more common vintage Japanese rides. Price—$500 to $2000.

1961-68 Honda CB/CL77, Super Hawk, or Scrambler

The Hondas of legend, the ones upon which a generation of riders began their riding careers. By now, most are lovingly cared for. If you find a junky one, buy it in spite of its condition. Restoration will be easy and relatively cheap. Because they were the first of the line, the CB/CL72 250s are especially desirable. The 305s, however, are more common and more usable. Price for a complete, unrestored bike with an unseized engine should go from $200 to $1000.

Untapped? What about Triumph, BSA, Harley-Davidson and all the rest? Essentially, seen through the 20/ 20 perspective afforded by more than two decades of hindsight, these were small-time manufacturers, almost by definition specialized and myopic. To realize how true that is, just think about how You Meet The Nicest People on a Honda, and about how that one clever slogan completely changed the way Americans looked at and thought about motorcycles.

1963-69 Honda CA72/77 Dream

Unlovely beasts, with strange styling and leading-link front suspension. There exists growing demand for these, especially from distaff riders/collectors. This may be the sleeper of collectible Hondas. Again, the 250 is the more desirable of the two, while the 305 is the more roadworthy. Price—$200 to $1000.

Now, with prices of classic British bikes well past the stage where they're merely on the rise, with the bikes themselves more difficult than ever to obtain, and most importantly, with the interest in them mostly sated, the next generation of motorcycle collectors is making known its enthusiasm.

That generation is the one that discovered the Japanese motorcycle, and yes. the one discovered by the Japanese motorcycle. It now is rediscovering the Japanese motorcycle. Those who study such things tell us such phenomenon are circular and recurring, and involve men and women typically in their late 30s and early 40s. Their kids are mostly grown, their careers have gone well enough that they find themselves with a small bit of disposable income, some spare time, and a healthy hunk of desire to own the machines that delighted them in their late youth and early adulthood.

1969 Honda CB750

The most desirable classic Honda? Might just be this one. For a CB750 Four to be truly collectible, however, it’s got to have the original sand-cast engine cases instead of the later die-cast versions, and it's got to be a stocker. Definitely worth looking for. Price$1000 to $5000.

That's how John Armstrong, one of the leading lights of the Vintage Japanese Motorcycle C lub, became reinvolved in motorcycles.

Both Armstrong and the club are based in Ontario, Canada. But the club has about 1200 members in branches in the U.S., Britain and Europe. And Armstrong says the story with clubmembers is much the same as his own: “I think these are probably the bikes people got started on. They may have been out of motorcycles fora number of years, or perhaps gone on to more modern equipment. And then they see an old Elonda Hawk, and they say. ‘Gee. I'd love to have one of those.' It’s almost a nostalgia sort of thing. They get the bug and start a collection.”

1959-62 Honda CB92 Benly

Not terribly fast, not terribly reliable, this bike, with its magnesium hubs and aluminum tank and sidepanels, nevertheless was Honda's first production sportbike. Expect to pay important money for a good one, especially if it’s a CB92R, complete with megaphone and racing seat. Price—$2000 to $8000.

What to collect? Tim Means of Los Angeles's V.IMC advises, “The one to buy is the one you want, the one you remember.”

There are several caveats, however. One of them is that for a bike to qualify as a “vintage Japanese motorcycle.” at least within the club's definition. it has to be I 5 years old. Another of them is that according to Armstrong. Means and other colleetors, some bikes are easier to buy, restore and ride than others.

1969 Kawasaki H1

Terrible handling, worse brakes, but what a motor! This bike’s 500cc, two-stroke Triple could smoke—both literally and figuratively—just about any other stock bike it came up against. A very entertaining ride. Production ran through 1976, but the first year’s version is the one to collect. Price—$600 to $800.

Bill Silver, the VJMC's Southern California rep, says interest in old Hondas remains so high that most of the VJMC’s member bikes are of that marque. The reason, he says, is simple: “There are parts out there to restore any Honda ever sold in the U.S.” Means, a Honda enthusiast and collector, agrees. “Restoring one is just a matter of going and buying the parts,” he says.

Finding parts for other marques is much more problematic. Says Armstrong. “After Honda, Kawasakis are the next easiest to find parts for. They're pretty good for mechanical parts, though cosmetic parts are tough; you've got to find a dealer who’s got something on his shelf. Next comes Suzuki, and, finally, Yamaha. Yamahas are very tough to get parts for, especially older bikes. It’s almost impossible.”

Equally difficult to find are parts for Marushos, Lilacs and other oddball rarities from Japan. But not impossible, as long as the would-be collector thinks in terms of using what has developed into a worldwide network of fellow collectors.

1973 Kawasaki Z1

The first superbike? Perhaps. Certainly the first machine to successfully challenge the performance and sales supremacy of Honda’s wonderful CB750, and the bike upon which Kawasaki's four-stroke performance image was built. Production ran through 1975, but the 1973 model is the one collectors will want. Price— $800 to $1000.

Particularly difficult to find, according to Jim Smith, a California collector who yearns for both Hondas and Yamahas, are Yamaha crankcase seals, especially the center seals for two-cylinder, two-stroke engines. This is particularly troublesome, he says, because when one finds an old Yamaha, the likelihood that it will need seals is very great.

Adding fuel to the old two-stroke vs. four-stroke controversy is the apparent rideahility of even the most crudely stored old Honda. Means says old Hawks, Scramblers, Dreams and Super Hawks usually need little more than fresh gas, fresh oil, a bit of attention to their carburetors, and most will light right up.

This rarely is true of bikes from other makers, he says. “I've got a friend with a Suzuki X6 Hustler,” says Means. “It took four motors and two complete chassis to rebuild that one bike. For things like grips, levers and tank badges, Honda’s the only company that's got all the stuff.” Or most all of it. He admits that some plastic Honda tank badges are unobtainable.

According to Smith, if something like an old Yamaha is the required tinder for relighting your motorcycling fires, “Try not to buy a real obscure model, go into it with the knowledge that parts are really difficult to locate, and join the VJMC (Holly Garrett, Membership Chairman. VJMC, 146 Fallingbrook Dr., Ancaster. Ontario L9G 1E6 Canada). The members are really helpful. I'm finding that it is possible to get the stuff. You just really have to look hard.”

1966-67 Suzuki X6 Hustler

The bike that put Suzuki in the performance business, this is a 250cc Twin with a six-speed transmission and a chassis that knows how to deal with corners. The bikes are rare and parts are tough to find, but a restoration will be worth the effort. Price—$400 to $600.

Once you find the parts you need to complete a restoration project, the payoff is worth the trouble, the collectors all agree. Says Means, “These old bikes are special. They’re reliable and they’re fun to ride. They're less expensive to rebuild than an old British bike, and once you get one rebuilt, you can really ride it.”

For most people, becoming involved means finding an old Japanese bike, and that, apparently, isn't all that difficult to do. Collectors interviewed for this story all said their best sources are local classified-ad publications known by such names as I he Big Nickel, The Recycler,; 77íe Benny Saver and others. Prices depend entirely upon the bike. If the bike isa common model, of moderate or small displacement, and is not now in good shape, it might sell for $50 or less. A clean runner being sold by a non-collector might sell for from $200 to $800. Such machines as Honda CB75()s, early Kawasaki Zls and H Is—rare bikes all—go for stout prices. And a restored example of something like a Honda CB92 Benly might require more than $ 10,000.

1959-66 Yamaha YDT1/YDS

A family of two-stroke Twins with more similarities than differences. These similarities include oil injection and a challenging unavailability of parts. These will be tough to find and even tougher to restore, but very satisfying when the job is complete. Price—$300 to $1000.

f he prices attached to vintage Japanese motorcycles have risen considerably in the last few years in large part, according to collectors, because of feverish enthusiasm for them in their country of origin.

“They have a devotion to motorcycling that's unrivaled over here,” says Silver, who has shipped old Japanese bikes back to Japan. “They're buying huge quantities of Super Hawks and Scramblers, they're buying the parts, and they're restoring them. It's a real strong market, and a lot of people are scouring the U.S. countryside for bikes and parts,” he says.

1964-66 Yamaha Big Bear Scrambler

Yamaha’s answer to Honda’s justly famed 305 Scramblers, these early dual-purpose machines wore high pipes, knobby tires and were balls of fun to ride. Not for motocross, and because of the difficulty of finding parts, also not for those who lack patience. Price—$400 to $1200.

Such talk makes Means crazy. He says, “That makes it hard for American enthusiasts. The demand for those bikes there is what's driving the prices for them here. It's ridiculous. I see it getting really ugly. The Japanese aren't gonna stop.”

Armstrong agrees. He says of his hobby. “It's still affordable, but it’s hard to tell how much longer it'll remain that way. Last year on the British market, a restored, mint. Super Hawk sold for about $ 1 5,000. That's scary, it's way high.”

That it may be. But it's also a piece of fitting, if belated, recognition of just how much the Super Hawk, and all its Japanese relatives, changed the face of motorcycling. Now, such a bike is a tiny sliver of history. But when it was new it was inexpensive, reliable, socially acceptable transportation. And oh, it was fun.

Is it any wonder, then, that people of a certain age find themselves coping with a reborn enthusiasm for the bikes of their youth? Especially when most of them are still inexpensive, still reliable, still fun.

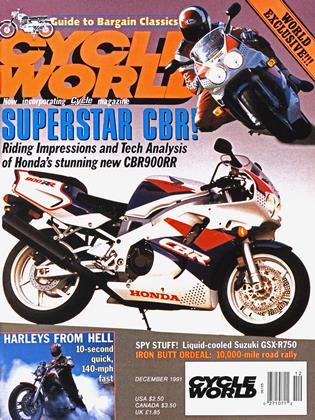

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

December 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1991 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

December 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1991 -

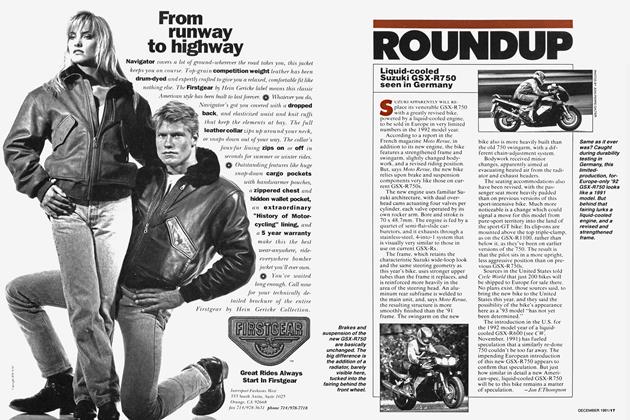

Roundup

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Suzuki Gsx-R750 Seen In Germany

December 1991 By Jon F.Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Reinvents the Rokon

December 1991 By Jon F. Thompson