THE TRANS-SOUTH-AMERICA RALLY

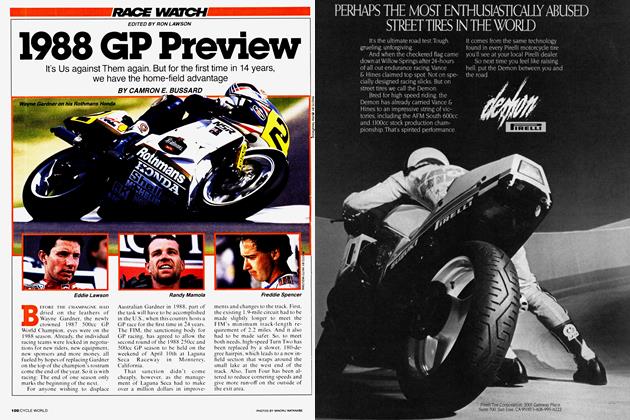

RACE WATCH

It almost didn't start, and same thought it would. never end

RON LAWSON

SO YOU THINK THE BAJA 1000 IS a long race, do you? Or is the Iron Butt Rally your idea of tough? Well, a handful of Americans who just returned from South America would beg to differ. They competed in the inaugural Trans-South-America Rally. and they'll be glad to tell you that it was a, longer, more-demanding event than has ever been held in this half of the world. The rally was cast in the mold of the infamous Paris-To-Dakar, meaning that riders must spend not hours, not days, but weeks in the saddle.

But this isn't a race for everyone; primarily designed for cars and trucks, it drew only a few very hardy motorcyclists. The event spanned 24 days and 7800 miles, starting in Cartagena, Colombia, and ending almost a month later in Buenos Aires after passing through five countries. In the process, the route passed through the treacherous Andes Mountains four times.

But the toughest obstacle the riders faced wasn't any jungle, mountain or desert; the hardest part came before the event even started. Michel JeanPierre, president of the Exploration Society of America, the group that originally put the rally together, made an announcement in Colombia just days before the event was to begin: The rally did not have sufficient funding. Sponsors had failed to materialize, so there would be no rally. Thank you very much, now go home.

For the 80 or so drivers and riders who had already spent thousands of dollars apiece and traveled from all over the world, that simply wasn’t an acceptable alternative. They had come to have a rally, and by God, they were going to have one. They formed a committee to analyze just what it would take to put on a rally themselves, and then they made it happen.

To do so, however, the competitors had to come up with a total of $160,000 to pay the various South American automobile federations, and to insure the event with Lloyds of London. The committee, comprising car drivers Dan Pedemonte, Bob Prado, John Bearce and Roger Miles, encouraged donations from the riders and drivers. “It was amazing—I think we made racing history,” Prado said later. “There we were in my hotel room with $160,000 in francs, pounds, cashier’s checks, just spread out all over my bed. We raised that much cash in just 48 hours.”

As a consequence, an event that was organized almost overnight by the participants came to be. The old name, the Trans-Amazon, was discarded, and the event was redubbed the Trans-South-America Rally.

And it was a tough one. Of 80 starters, there were only about 10 legitimate finishers, three of them motorcyclists. About 20 others finished, but outside of the allotted time. In the course of the rally, there were dozens of major obstacles the survivors had .to overcome. A landslide covered much of the course at one point; motorcyclist Rob Shirley and a handful of others were the only ones

to emerge on the other side. So, the rally’s schedule was altered to allow other teams to get back in the race. Some didn't make it, like Americans Roger Pattison and Atkins Burreli, both Honda XR2 50-mounted. “Even after they gave us time to cateh up. we couldn't do it," Pattison said later.

Local traffic took its toll on the event, as well. In the early days of the rally, Japanese rider Kengo Okamoto diced with Shirley for the lead in the motorcycle division, but his race ended abruptly when he collided with a truck.

When it was all over, though, Rob Shirley had survived everything to win the motorcycle competition. The American founder of Mastercraft Ski Boats, Shirley rode a Kawasaki KLR650 prepared by former National Enduro Champion Dick Burleson; and he had anything but a flawless rally, struggling to find gas and get directions from locals in some places. But he perhaps had it easy compared to Robin Bennett, who finished in second place with a broken shoulder on a KTM 600. The third official motorcycle finisher was Steve Maloney on a Cagiva Elefant. But without a doubt, the most notable ride was put in by 62-year-old Charles Peet, who rode the entire course on a three-year-old HarleyDavidson police bike. “At the start they were laying I000-to-one odds against me.” Peet laughs. “But I made it.”

At the end of the rally in Buenos Aires, driver/committee-member Pedemonte handed out all the awards, and presented a special one to Peet for being “the toughest man in the rally.” But the fact that the rally even happened is a trophy that they all will have forever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue