Six DAYS IN SEPTEMBER

RACE WATCH

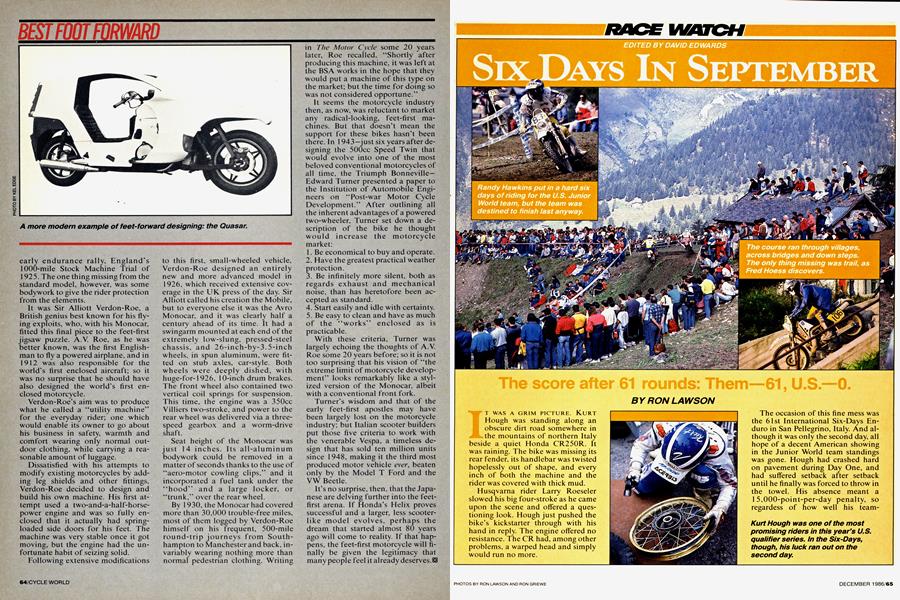

The score after 61 rounds: Them-61, U.S.-0.

DAVID EDWARDS

RON LAWSON

IT WAS A GRIM PICTURE. KURT Hough was standing along an obscure dirt road somewhere in the mountains of northern Italy beside a quiet Honda CR250R. It was raining. The bike was missing its rear fender, its handlebar was twisted hopelessly out of shape, and every inch of both the machine and the rider was covered with thick mud.

Husqvarna rider Larry Roeseler slowed his big four-stroke as he came upon the scene and offered a questioning look. Hough just pushed the bike’s kickstarter through with his hand in reply. The engine offered no resistance. The CR had, among other problems, a warped head and simply would run no more.

The occasion of this fine mess was the 61st International Six-Days Enduro in San Pellegrino, Italy. And although it was only the second day, all hope of a decent American showing in the Junior World team standings was gone. Hough had crashed hard on pavement during Day One, and had suffered setback after setback until he finally was forced to throw in the towel. His absence meant a 1 5,000-point-per-day penalty, so regardess of how well his teammates—Fred Hoess, Jeff Russell and Randy Hawkins—did, the group effort would be for nothing.

But that wasn’t the end of all U.S. hope. Because there wasn’t just one American team at this year's ISDE, but nine. There was the Junior World team, which is a class meant to showcase a country’s youngest talent; the age limit for these riders is 23 years. Then there was the usual six-man Trophy team intended to represent the very best a country has to offer. Additionally, the U.S. had several three-man teams riding for clubs or manufacturers. Altogether, the total number of American riders in Italy this year was 28.

So even though 15,000 points a day would be heaped on America’s Junior World teamsters from Day Two onward, our Trophy and club teams still looked to be in the hunt. In particular, the Trophy team of Fritz Kadlec, Larry Roeseler, David Bertram, Charles Halcomb, Geoff Ballard and Chuck Miller seemed like an unstoppable combination. But America has had strong Trophy teams before, and still had never won. The closest the U.S. ever came was second in 1982. Even when the Six-Days was held in Massachusetts in 1973, the U.S. Trophy team could only manage a fifth. Every other year, the U.S. has struggled just to finish in the upper half of the pack.

That might seem strange to an American public that has grown accustomed to seeing its riders defeat the best that the rest of the world could offer. But Eddie Lawson, Ricky Johnson and other world-beating Yankees have one very big advantage over their enduro counterparts: money. Enduro riders don't have big Japanese manufacturers picking up the tabs or supplying endless shipments of spare parts, and their pit crews usually consist of moms, dads, sisters and girlfriends. A handful of Americans do have manufacturer support, most of it from Husqvarna, although Can-Am, KTM and Kawasaki also have small programs. But all are extremely modest.

Kawasaki’s Public Relations director, Mel Moore, put it all in perspective. “Jeff Fredette is cheap. He’ll go to a national enduro for us and send me a $79 bill for gas. I’ll ask about hotels and meals, and he just says he slept in his truck and brought his own food.” Fredette knows he’s the only rider who Kawasaki supports at all, and is grateful for what he gets.

For most ISDE riders, the only financial aid comes from the AMA’s rider support fund, headed by Dick France. He relies on donations and T-shirt sales in hopes of getting enough money to buy gas for the riders and perhaps a tire or two.

Aside from the financial problems

involved in just getting our riders to Europe, there are political matters to contend with. In Italy, for example, nobody was going to beat the home team. The Italians saw to that. See, riding a Six-Days involves two separate skills: You have to be a fast trail rider and a good motocrosser. The Americans are fast trail riders. The Italians are good motocrossers. Therefore, the ISDE course in Italy involved very little trail. Most of the course was actually on paved mountain roads, and the event was designed to be decided on the motocross-style special tests. When the Americans saw those tests for the first time, most of the turns clearly had been practiced on; during the previous two weeks, the Italian team had a training camp based at the site of the event. They had the entire deck stacked in their favor.

But with the rain of Day Two, the Italians saw their plans backfire. The trail became extremely difficult, and the Italian riders struggled. The U.S., on the other hand, shined.

But the Italian organizers had a solution to that problem. They went before the FIM jury, which has a member representing each country, and proposed to throw out the entire second half of the day. Deals were made, winks exchanged, and the jury voted and ratified the proposal.

Not so coincidentally, the next morning saw more riders start than had finished the night before. There were whispers and mutterings that several countries that had lost riders that day were allowed to repair their motorcycles and get back into competiton. That option was not made available to Kurt Hough and the U.S. team.

So the next day, the sun was out and the Italian were still winning. But the trails were still muddy—again, not prime conditions for the track-bred Italian team. The Italian clerk of the course solved that problem by simply cutting out most of the trail sections. Thus, Day Three of the 61 st International Six Days Enduro was run almost entirely on pavement.

But every decision didn’t go against the U.S. On the morning of Day Three, Charles Halcomb was misdirected by an official and got lost. That cost him three minutes at the next check. Hugh Flemming, America’s jury delegate, went to the meeting that night to do battle once again; and in a decision that surprised Flemming as much as anyone, the jury declared that the foul-up wasn’t Halcomb’s fault, and the threeminute penalty was removed.

Another bright spot was the final moto. On the last of the six days, the riders were all put on a natural-terrain motocross where they could race against each other, rather than against the clock. Naturally, the Italians were expected to flaunt their MX skills. But unlike the special test on the previous days, the track was a complete virgin. Not one blade of grass had jeen bent by a motorcycle tire. At1 ist, the rest of the world was on eq» al footing with the Italians, and t\e tides began to turn.

T íe Italians won the first few ra' es, but the Germans, the Swedes, e en the Australians all won, too. vnd so did the U.S. After Halcomb, Tim Shepard and Fred Hoess all made serious challenges in their respective races, Alan Wickstrand finally took a win.

This caused a strange scenario. The normally overenthusiastic Italian crowd lined the track, but instead of waving flags and shooting cries of support, they were dead-quiet. The Italian flags were still, and there was

only an occasional cheer from a rare American supporter.

Then, in a later 500cc moto, Bob Bean put America in front again. Once more, the crowd was silent. It wasn’t until one of the last races of the day, one in which the top fourstroke riders were grouped together, that the crowd’s attitude began to change. Larry Roeseler grabbed the holeshot and proceeded to put on such a spectacular show of riding skill that the Italian crowd couldn’t help but cheer. Roeseler began to feed ön the crowd’s enthusiasm and made jumps where there were only bumps, and flew down hills where other riders would lock up the brakes.

The crowd loved it. But they could afford to love it. Roeseler wasn’t in contention for the class win—that was already the property of Italian Guglielmo Andreini, and he was far enough behind Roeseler in that moto that there was no sense in cheering for him. Instead, the crowd took on a distinctively pro-American attitude.

Besides, no matter how the last moto went, the Italians knew that this was destined to be their SixDays. When the scores were figured, there was a virtual tie for the top individual, both of which were Italians. Grasso Giorgio was given the individual overall win, with Tullio Pellegrinelli less than one second back. And Italian teams took both the Trophy and Junior World competitions. Fritz Kadlec finished as the seventh Open-class bike to lead the U.S. Trophy team to sixth overall. But our Junior World team was 13th.

All this might make you wonder what would it take for Americans to win a Six-Days. Husky’s Dick Burleson has some ideas, and doesn’t mind talking about them. “We would have to have the event in our own country and turn everything to our advantage, just like they do in Europe. In our case that would mean having it somewhere like Las Vegas, and filling our team with desert racers who can handle 1 OO-mile-an-hour sections. No other country has a Vegas. That’s the type of thing they do when we go over there.”

Hugh Flemming has a more optimistic outlook. “It’ll take an event with some really tough trails. In the really difficult stuff, our riders are as good as any in the world.” Then Flemming offers a ray of hope. “That’s exactly the type of event we expect in Poland next year.” S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

December 1986 By Paul Dean -

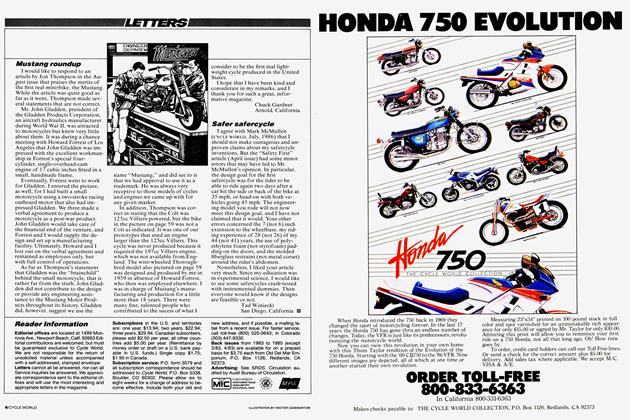

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1986 -

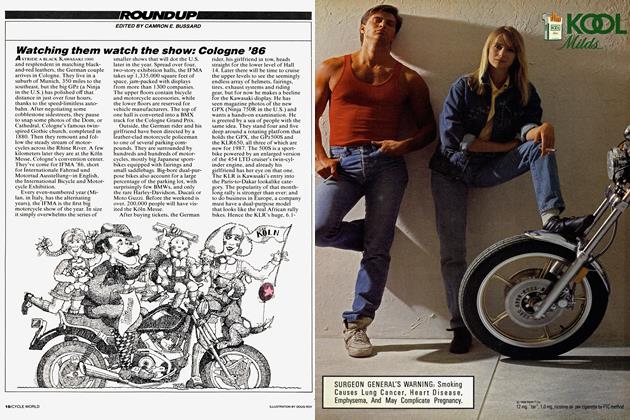

Roundup

RoundupWatching Them Watch the Show: Cologne '86

December 1986 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

December 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

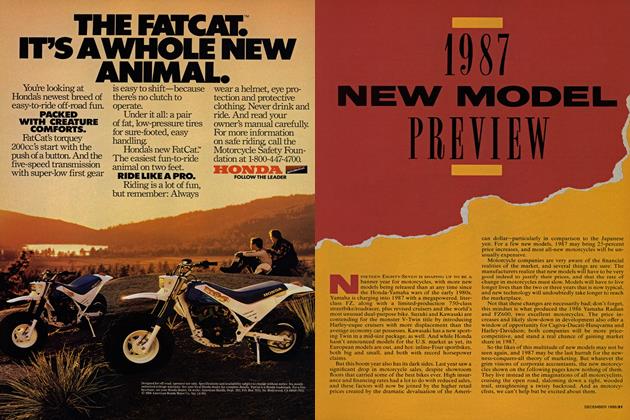

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions1987 New Model Preview

December 1986