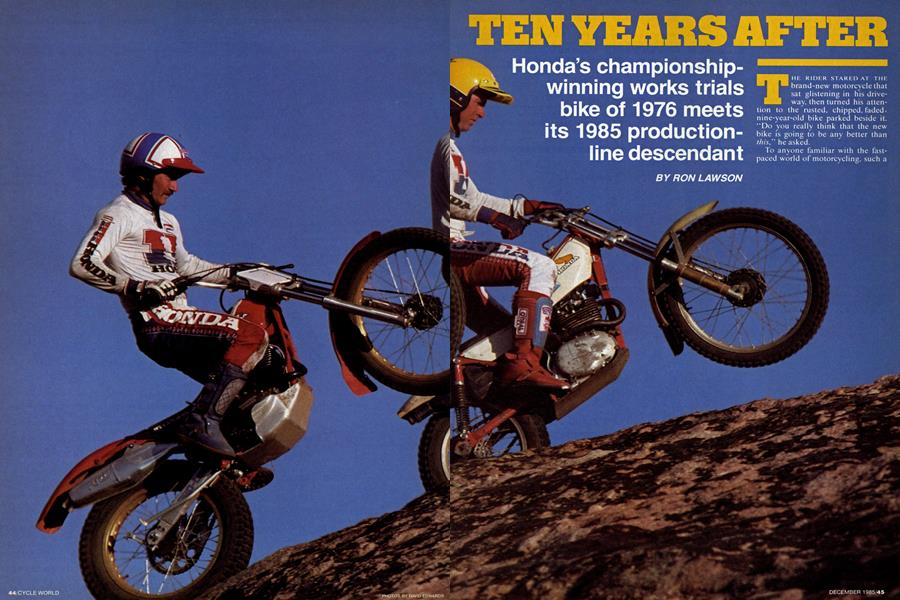

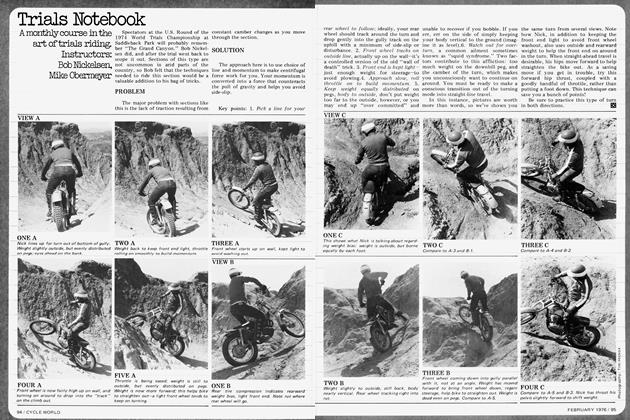

TEN YEARS AFTER

Honda’s championship-winning works trials bike of 1976 meets its 1985 production-line descendant

RON LAWSON

THE RIDER STARED AT THE brand-new motorcycle that sat glistening in his driveway, then turned his attention to the rusted, chipped, faded-nine-year-old bike parked beside it. “Do you really think that the new bike is going to be any better than this," he asked.

To anyone familiar with the fastpaced world of motorcycling, such a question would have seemed too ludicrous to ask. It was unimaginable that any motorcycle built in 1975, no matter how good it had been then, could hold a candle to even the worst of today’s hardware.

What’s more, the old bike looked like it hadn’t been much to start with. Its engine cases were sand-cast and porous-looking, baked-on oil had discolored the fins, and the fiberglass gas tank/seat combination was cracked and yellowed. Indeed, the bike could just as easily have been 20 years old.

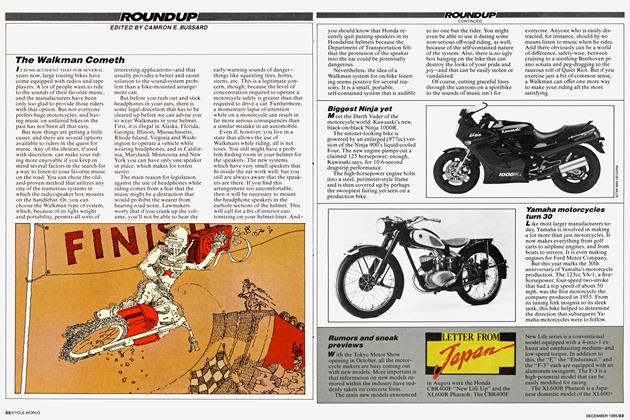

But this was no ordinary motorcycle, not nine years ago, not today. In 1976, it was a trials bike such as the world had never before seen. It was called the RTL300, and it was a $23,000 example of Honda muscleflexing. It was ridden back then by Marland Whaley, who took the bike to two of the three national trials championships he earned for Honda—and who was now standing in his driveway, contemplating the differenced between that old bike and the brand-new one parked next to it. With the minimal amount of progress that trials technology seems to have made over the last 10 years, Whaley’s skepticism about the new machine was well-founded.

The new motorcycle was a Honda RTL250, a limited-production trials bike turned out by Honda Racing Corporation, the same branch of the Honda empire that built Freddie Spencer’s NS500. The RTL250 represents the modern state-of-the-art in trials bikes: a single-shock, ultralightweight, highly expensive piece of machinery. It also is not officially available in America, although there are rumors that Honda will make a few of them available to serious trials riders in this country. Despite sharing the same first letters, the two RTLs have almost nothing in common, aside from being four-stroke Singles built by Honda. Perhaps this is a hint that times have changed, even in the world of trials. That, in fact, is why they and Whaley had been brought together—to see if, in this case, change and progress equated to the same thing. Whaley was about to spend a few hours riding both machines, which would jog his memory and help him recall both the good times and the bad, the victories and the defeats he had experienced on the RTL300. It would also be his first encounter with an RTL250, a bike that came along after he left Honda.

That such a comparison was even possible is a story in itself. When Whaley walked away from Honda in 1978, the RTL300s were deposited in a dark corner of Honda’s Gardena, California, warehouse and forgotten. Like most huge corporations, Honda has little in the way of sentiment. Of the nine RTL300s left, several went to Europe to help get the works trials program underway there. Honda had no use for the remaining bikes so they were to be fed to the crusher, their value in scrap metal outweighing their worth as pieces of history.

But at the last minute they were snatched from the jaws of the crusher. Their savior was Mr. I. Shimizu, a top-line executive at Honda who had enough sentimentality to be interested in the RTLs, and enough rank to save them. Thus the RTLs were spared, although they sat unridden and forgotten—until now.

Whaley’s first reaction when the 300 was unloaded was one of uncertainty: “This wasn’t mine. I never thrashed a bike like this.” The 300 did look bad; the years of neglect had taken their toll. But Whaley examined the bike more closely, catching a familiar scratch here, a telltale blot of paint there. Finally he confessed. “This engine was mine in Scotland. See the purple paint? That’s how they marked the bikes at the Scottish SixDays Trial. But I never used this frame; I used the long swingarm, and this is the short one. Mark Eggar probably was last to ride this bike.

“We would never DNF on these things. They were really reliable . . . plus, Bob Nickelsen (the team manager) would show up on the trail behind us with whatever we needed,” Whaley recalled. “The bikes were good, but the main advantage was Honda’s support. We would fly out and stay in the best hotels.”

A few hours later, after riding both machines over and around the hills near his Santee, California, home, Whaley wasn’t so positive about his recollections of the RTL300’s performance. “This thing makes a lot of noise and doesn’t go anywhere,” he exclaimed after climbing a ledge on the 300. “The bike doesn’t feel wornout or anything. It’s just that 18mm carb. These were always slow.”

The old RTL is, in fact, slow-revving, a condition brought about mainly by the tiny carb needed to give the engine crisp throttle response at low rpm. And the 300 is also slow-handling and slow-moving compared to the new RTL. In its day, the RTL300 was considered radical, even twitchy, but now it seems ultraconservative. The RTL250 leaves much less room for error. The 300 plods through sections; the 250 attacks them. The 300 forgives all but the most blatant errors; the 250 is mercilessly sensitive to rider input. The 300 requires a pegged throttle, gritted teeth and a lot of determination to climb a steep section; the new 250 whisks up hills before the rider can even consider his actions.

So trials machinery has, indeed, changed; but then, so has the sport of trials. In 1976, trials bikes were designed for the masses, but as it turned out, the masses didn’t care that much for trials bikes. America quickly lost what little interest it had in trials, and the sport shrank in size until there was no one left except the hardcore enthusiasts. Now, with the novice elements of trials distilled away, the machinery has become more and more attuned to seasoned riders.

So it wasn’t surprising that, after a short period of adjustment, Whaley began cleaning sections on the new RTL that he had never cleaned before. Even though he had been away from the professional trials scene for years, he still is among the best feetuppers in the country, and the new RTL was to his liking. And despite his early skepticism, he didn’t seem all that surprised at the capabilities of the new RTL. He did concede that with new tires and shocks, the old bike could probably clean the same sections as the new one, but, he said, it would be more work. The newer RTL250 would still have more power, better suspension and more responsive handling.

After the RTL’s short-lived resurrection, it would once again part company with Whaley and go back to Honda to rest in the same dark corner where it had stood before. But now, at least, there would be no unanswered questions. By day’s end a verdict had been reached: The RTL300’s time had passed. Progress had been victorious once again. So, even in the most obscure avenues of motorcycling, time moves on. It’s just that in observed trials, it seems to move more slowly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

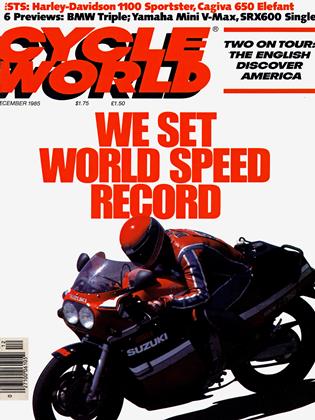

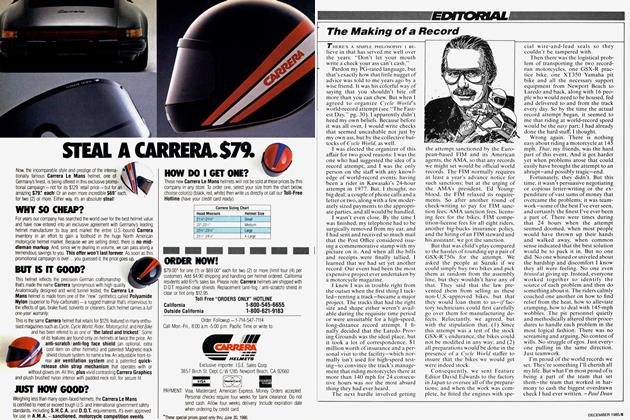

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart