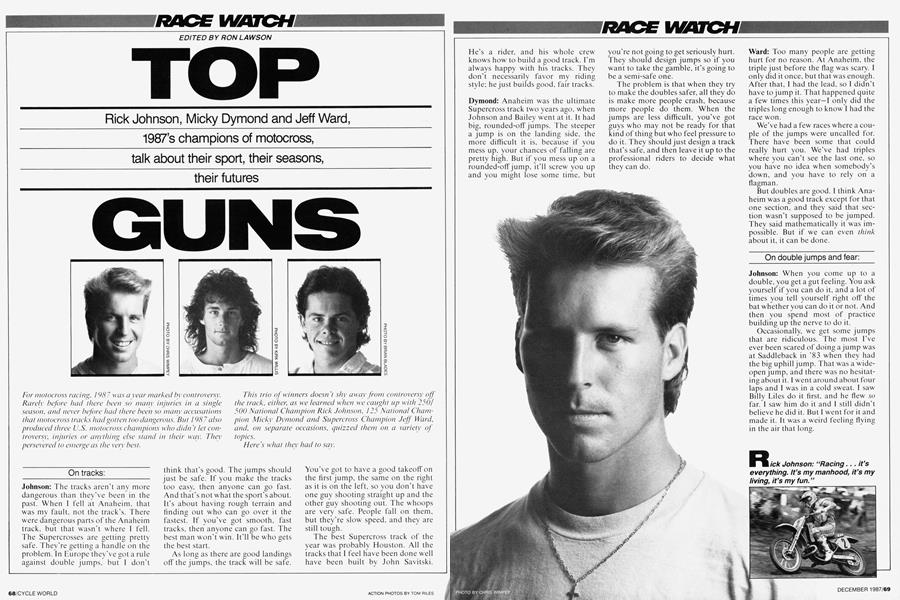

TOP GUNS

RACE WATCH

Rick Johnson, Micky Dymond and Jeff Ward, 1987’s champions of motocross, talk about their sport, their seasons, their futures

RON LAWSON

For motocross racing, 1987 was a year marked by controversy. Rarely before had there been so many injuries in a single season, and never before had there been so many accusations that motocross tracks had gotten too dangerous. But 1987 also produced three U.S. motocross champions who didn't let controversy, injuries or anything else stand in their way. They persevered to emerge as the very best.

This trio of winners doesn't shy away from controversy off the track, either, as we learned when we caught up with 250/ 500 National Champion Rick Johnson, 125 National Champion Micky Dymond and Supercross Champion Jeff Ward, and, on separate occasions, quizzed them on a variety of topics.

Here's what they had to say.

On tracks:

Johnson: The tracks aren't any more dangerous than they've been in the past. When I fell at Anaheim, that was my fault, not the track’s. There were dangerous parts of the Anaheim track, but that wasn't where I fell. The Supercrosses are getting pretty safe. They're getting a handle on the problem. In Europe they've got a rule against double jumps, but I don't think that's good. The jumps should just be safe. If you make the tracks too easy, then anyone can go fast. And that's not what the sport'sabout. It's about having rough terrain and finding out who can go over it the fastest. If you’ve got smooth, fast tracks, then anyone can go fast. The best man won't win. It'll be who gets the best start.

As long as there are good landings off the jumps, the track will be safe. You've got to have a good takeoff on the first jump, the same on the right as it is on the left, so you don't have one guy shooting straight up and the other guy shooting out. The whoops are very safe. People fall on them, but they’re slow speed, and they are still tough.

The best Supercross track of the year was probably Houston. All the tracks that I feel have been done well have been built by John Savitski. He’s a rider, and his whole crew knows how to build a good track. I'm always happy with his tracks. They don't necessarily favor my riding style; he just builds good, fair tracks.

Dymond: Anaheim was the ultimate Supercross track two years ago, when Johnson and Bailey went at it. It had big, rounded-off jumps. The steeper a jump is on the landing side, the more difficult it is, because if you mess up, your chances of falling are pretty high. But if you mess up on a rounded-off jump, it'll screw you up and you might lose some time, but

you're not going to get seriously hurt. They should design jumps so if you want to take the gamble, it’s going to be a semi-safe one.

The problem is that when they try to make the doubles safer, all they do is make more people crash, because more people do them. When the jumps are less difficult, you’ve got guys who may not be ready for that kind of thing but who feel pressure to do it. They should just design a track that’s safe, and then leave it up to the professional riders to decide what they can do.

Ward: Too many people are getting hurt for no reason. At Anaheim, the triple just before the flag was scary. I only did it once, but that was enough. After that, I had the lead, so I didn't have to jump it. That happened quite a few times this year—I only did the triples long enough to know I had the race won.

We’ve had a few races where a couple of the jumps were uncalled for. There have been some that could really hurt you. We’ve had triples where you can’t see the last one, so you have no idea when somebody’s down, and you have to rely on a flagman.

But doubles are good. I think Anaheim was a good track except for that one section, and they said that section wasn’t supposed to be jumped. They said mathematically it was impossible. But if we can even think about it, it can be done.

On double jumps and fear:

Johnson: When you come up to a double, you get a gut feeling. You ask yourself if you can do it, and a lot of times you tell yourself right off the bat whether you can do it or not. And then you spend most of practice building up the nerve to do it.

Occasionally, we get some jumps that are ridiculous. The most I've ever been scared of doing a jump was at Saddleback in '83 when they had the big uphill jump. That was a wideopen jump, and there was no hesitating about it. I went around about four laps and I was in a cold sweat. I saw Billy Liles do it first, and he flew so far. I saw him do it and I still didn't believe he did it. But I went for it and made it. It was a weird feeling flying in the air that long.

Dymond: If a double is something I’m not sure about, usually I’ll watch someone else. Sometimes I make up my mind that I’m going to do it when I’m walking the track—like the triples before the finish line at Anaheim. If I hadn’t made up my mind that I was going to do those, I don’t think anyone else would have done them that night. There was no run, and you had to hit the jump so hard that it collapsed the suspension. It was tricky and neat. When your mind is made up, your wrist just turns and you do it. Usually you make it. I might crash on some little thing, but I usually get the concentration up for the big ones. The first time you do it, it’s great. It’s scary, but it’s a total rush. It’s hard to explain. When you do something like that you know you've done something spectacular. You hear the people yell, and you continue to do your job. But you remember those things when you come back to the pits.

Ward: It's all luck. We're all scared of the doubles, but you just come up to them at the speed you think you need to make it. Sometimes the last jump will be at the start of a bunch of stutter bumps, so you can't just clear it by 0 feet, or sometimes you land in the stutter bumps. You've got to do it just perfect. That’s where Ricky broke his finger—after a bunch of triples leading into stutters.

On the ’87 season and injuries:

Johnson: My injuries started out in January at Carlsbad, when I crashed during a qualifier for the Golden State series. I separated my ribs from my spine and slipped a disc in my back. I had just gotten over ankle surgery a week before that. Then I crashed at the first Supercross at Anaheim. I didn't really suffer any injuries there, I just knocked myself out. After that. I was fine all the way up to Pontiac, where I broke and dislocated my right ring finger, and sprained my middle finger and pinky finger. That’s it. I’ve been really fortunate.

Dymond: I started off the year in Supercross really strong, and I think I could have been a contender for the title, but I got sick. It was a virus that I probably had since I was a kid. It’s like mono or pneumonia; if you just ignore it, it gets worse and worse, and then you have to take some time off. Once I did that. I started getting real strong. In that month off, I would sleep all day without leaving the house. After a few weeks I started training. I'd sleep, wake up, train, and go back to sleep.

I was injured a few times this year and never really told anyone—so no one else would think they had an advantage. I broke my wrist at Michigan, and I already had damage in that same wrist. It was tough to hang on, but I managed to win that day. Another time I fell off and hurt my foot. And I broke my tailbone before Anaheim.

I know that Ward had a broken ankle all year. He was tough, though, and he kept it to himself. That’s hard—I had to do the same thing. People would come up and ask why 1 didn’t ride well that day. I wish I could have told them the truth, but I’d just say I had problems.

Ward: I trained really hard at the beginning of the year to get ready, and I got a big points lead because Rick crashed at Anaheim. If not for that, I can't say I would have beat him. Then I got hurt, and he was able to close in on me, and then he got hurt again, and it went back and forth. It was a long year, but I never gave up. I had to scratch the 250s off as soon as I broke my ankle, because outdoor races are a little different from indoor races. In Supercross you can time everything, and outdoors you’ve got to hang it out. I caught my foot too many times.

They were going to put a screw in my ankle, which would have permanently fixed it, but the bone shattered. so they had to cut the ligaments and go in and take all the bone fragments out. It took a long time to heal, and it still hurts today.

I hurt my ribs at Buchanan. Rick and I were tied for points in the 500s, and in practice there was this really big double —they shouldn't have them on outdoor tracks. I was in fourth gear, wide-open on the 500, and right before I took off. the crank snapped and the bike just stopped. I cleared the jumps, but I landed on my tailbone, broke it, and did my ribs in, too. I still rode the first moto and got second.

On why they win:

Johnson: I spread myself out so that I’m not the greatest at any one thing, but I'm good at all of them. The tougher the track, the better. The more physically demanding, the better. A track needs a lot of washboards and jumps that are rough—small jumps, big jumps, all kinds of stuff.

Dymond: If I were designing a track for me, I’d have a long section of whoops with a long straight before it, so if you wanted, you could just leave the throttle taped wide-open. That way, you could go faster if you wanted to. But now, you can only go as fast as the track will let you go. They don’t make the tracks difficult enough or give you an opportunity to stand out.

Ward: I think my advantage is in cornering. I used to be really bad in stutter bumps —I’d crash —but I go through them pretty good now. I really enjoy training, but you can train as hard as you want and you’re still going to get tired. The whole secret is learning how to ride while you’re tired, because tracks are going to beat you up. You just get to the point when you feel like you have to slow down, but you don’t. Any one of the kids out there can go as fast as us for a lap, and that’s why you see riders like Rick Ryan running up there with us. They stay out front for four laps, then they start falling back because they get tired and give up. They’ve got to learn to keep going.

On purse money:

Johnson: There needs to be more purse money. People flip out when I say I won L. A. and only made $ 1000. Daytona is really the only good-paying race; you can make $5000 there. On the outdoors you make $800 to $1000 if you win both motos. They should be able to do better.

Dymond: I think someone is getting away with all the money at the races. When I see them pack all those people into the stadiums, I can’t believe they pay us that tiny amount. If they only took a dollar out of every ticket, there would be a big purse. Even a rider’s union wouldn't help, because riders don’t stick together. If most of the riders say they won’t ride, there always are some who will. In the long run, it just kills us. But we’re doing it to ourselves. The Mafia probably wouldn’t even consider getting involved with motocross —it’s too screwed up.

Ward: It’s terrible, and it’s going downhill. I made $ 1500 winning Anaheim. I make my money from the factory, but the privateer looking to earn some money in racing can forget it. If he makes the main event, which is really good, the best he can hope for is last place, $400 or something.

On younger riders:

Johnson: If you take out Lechien and Ward, I would want Jeff Stanton and Donny Schmitt riding for me. I watch them and they put their heart into their riding. It isn’t enough for them to come out to the track on the weekend and be cool because they’re on a team. When you look in their eyes, you see they want something more than just to be a factory rider. They ride with their hearts, not just with their minds.

Dymond: I don’t know many riders personally. But there are a few guys out there who have the potential, who aren’t followers—like Donny Schmitt. You can see it in his eyes how bad he wants to succeed. He's not there to hang out with the other riders or to look like the other riders. He's out there to do his thing. He's got a lot going for him in the future. I know Erik Kehoe, George Holland, Jeff Leisk. Eddie Warren and Guy Cooperall can be 125 champion next year. Personally. I would like to see Guy Cooper win. He's just a great guy. He and his wife work so hard. I feel bad at the races because he's changing his tires while I'm sitting in my van being cool.

Ward: Ron Lechien used to be the rider who would come in and make us jump everything. He would jump stuff that we didn't do at all, and he'd do it for the whole race.

If I were team manager right now, I'd still stick with Lechien. He doesn't train, but if he got serious we'd all be in trouble. He'll get straightened out next year. though. He's on a really tight leash. He can still go as fast as anyone on the track any day he wants to. He's got the style and speed-he'll be around the longest.

Privateers? Mike Fisher's doing real good. Guy Cooper has always had the attitude it takes-he doesn't give up. But he hasn't had any good breaks. Maybe he doesn't have quite the natural ability, but he has the drive. He's kind of like Mark Barnett. Barnett never had the natural talent. but he gave so much effort and he never gave up. He really wanted it, and he trained so hard that it finally came to him.

On the future:

Johnson: I plan on being with Honda. I'm really happy with them. I'm happy with Brian Lunniss. my me chanic. He's done an excellent job for me and puts out 110 percent. I just want to ride, and get better and stronger.

I still enjoy racing, but I don't en joy traveling. If they had local races three times a week, I'd go race them. But I like to stay home, I like my friends, I like to go to the river and water ski, I like to go surfing. When you're sitting in Pennsylvania one weekend and in Atlanta the next, you don't get to be the person you would like to be a lot of the time. You fall short of being a friend to people. of being a son to your mother and fa ther. of being a brother to your sister, and a lot of times I’ve fallen short of being a boyfriend. My job is so demanding that it’s easy for it to overshadow other important things in life. But my racing is important to me right now. It’s everything. It’s my manhood, it’s my living, it’s my fun.

Eventually, I’d like to do what Roger De Coster is doing. I like working with younger riders, but I haven't been able to do it to the extent I would like to because it jeopardizes my own position. That sounds selfish—and it is selfish. I'd like to help up-and-coming riders more than I do, but there comes a time when I think, what if I help this kid and he shoves me out of a job? So I'm concentrating on myself. Î think I need to grow and help myself a lot right now.

Dymond: Next year I want to be a serious threat and win some races. Supercross holds a lot of opportunity for me. I think I'll really be able to go fast in the Supercrosses next year, because I won't have any health problems. I have a great trainer and doctor helping me. I don’t see how I can fail. After that, I don’t know. I want to be a dominant motorcycle racer, the best guy there is out there.

I spend so many Sunday nights flying home with the feeling that people don't think what I do is really that special. It is to me. And I think it should be.

Ward: My contract is up this year. I’ll probably go in on Thursday of this week and try to iron it out. Í want to get three more years. On the contract I’ve had up until now, I’ve ridden three years and gotten three championships.

After motocross, I think I'll take a few years off and do some triathlons and stuff. That’s why I like training and do a lot of swimming, running and cycling. I try to get good at those while I’m getting better at motocross.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialIdol Speculation

December 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeService Bulletins

December 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsDesmo Fever

December 1987 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1987 -

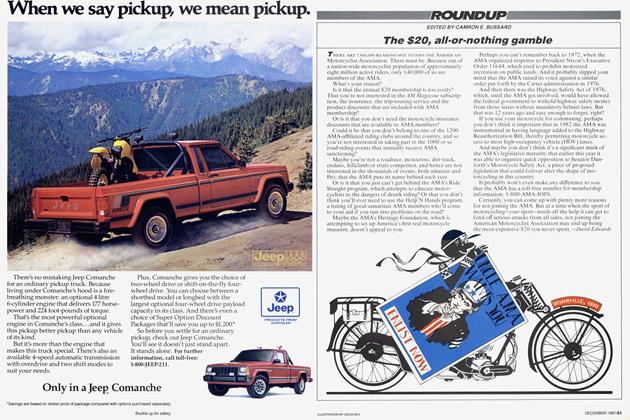

Roundup

RoundupThe $20, All-Or-Nothing Gamble

December 1987 By David Edwards -

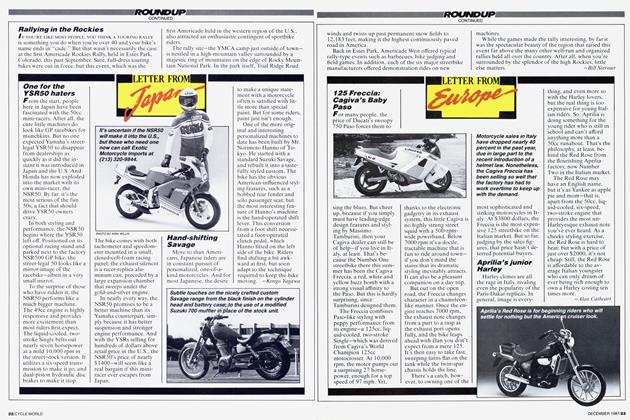

Roundup

RoundupRallying In the Rockies

December 1987 By Bill Stermer