Team Roberts vs. Suzuka

RACE WATCH

With the right coach, anything is possible.

RON LAWSON

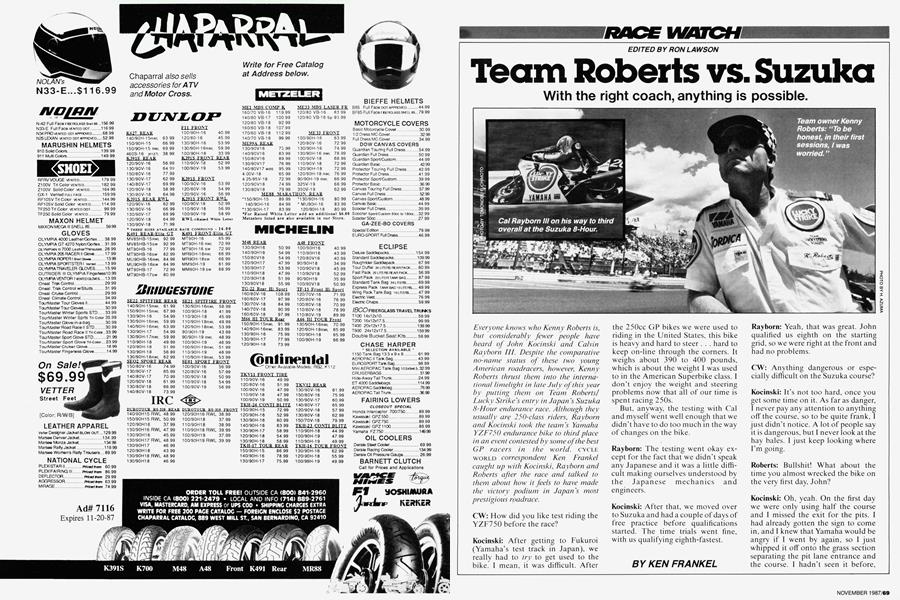

Everyone knows who Kenny Roberts is, but considerably fewer people have heard of John Kocinski and Calvin Rayborn III. Despite the comparative no-name status of these two young American roadracers, however, Kenny Roberts thrust them into the international limelight in late July of this year by putting them on Team Roberts/ Lucky Strike's entry in Japan's Suzuka 8-Hour endurance race. Although they usually are 250-class riders, Rayborn and Kocinski took the team's Yamaha YZF750 endurance bike to third place in an event contested by some of the best GP racers in the world. CYCLE WORLD correspondent Ken Frankel caught up with Kocinski, Rayborn and Roberts after the race and talked to them about how it feels to have made the victory podium in Japan's most prestigious roadrace.

CW: How did you like test riding the YZF750 before the race?

Kocinski: After getting to Fukuroi (Yamaha’s test track in Japan), we really had to try to get used to the bike. I mean, it was difficult. After the 250cc GP bikes we were used to riding in the United States, this bike is heavy and hard to steer . . . hard to keep on-line through the corners. It weighs about 390 to 400 pounds, which is about the weight I was used to in the American Superbike class. I don’t enjoy the weight and steering problems now that all of our time is spent racing 250s.

But, anyway, the testing with Cal and myself went well enough that we didn’t have to do too much in the way of changes on the bike.

Rayborn: The testing went okay except for the fact that we didn’t speak any Japanese and it was a little difficult making ourselves understood by the Japanese mechanics and engineers.

Kocinski: After that, we moved over to Suzuka and had a couple of days of free practice before qualifications started. The time trials went fine, with us qualifying eighth-fastest.

Rayborn: Yeah, that was great. John qualified us eighth on the starting grid, so we were right at the front and had no problems.

CW: Anything dangerous or especially difficult on the Suzuka course?

Kocinski: It’s not too hard, once you get some time on it. As far as danger, I never pay any attention to anything off the course, so to be quite frank, I just didn’t notice. A lot of people say it is dangerous, but I never look at the hay bales. I just keep looking where I’m going.

Roberts: Bullshit! What about the time you almost wrecked the bike on the very first day, John?

Kocinski: Oh, yeah. On the first day we were only using half the course and I missed the exit for the pits. I had already gotten the sign to come in, and I knew that Yamaha would be angry if I went by again, so I just whipped it off onto the grass section separating the pit lane entrance and the course. I hadn’t seen it before, but there was this concrete drain pipe running through the grass and I tried to jump it. The front tire caught the top edge and shoved the tire away. My feet were in the air and I almost crashed it right there. I saved it, but when I think about trying to explain to Kenny why I crashed in the grass, it makes me real nervous.

KEN FRANKEL

Roberts: You should be. You'd have to ride in the back of the bus without air conditioning.

Rayborn: I had one like that. On my second practice day I rode it off the track at 100 mph in Turn One on my very first lap. Normally, the guys go into the sand with the brakes on and get stuck. I didn't even slow down and just rode it across the sand and back on the track.

Roberts: That's where American riders' dirt-track experience really pays off.

CW: Did you have any problems with the Le Mans start?

Kocinski: No, I think I was the first one to get to the bike and Cal was holding it. I would have had a better start had the engine been warmed up because it died right off the start. But it turned out okay. It was a long race and we finished third.

Looking back and being realistic, I can see that there's no way you can win it at the start. I rode the first 55 minutes on the bike, starting off with l-minute, l 9-second lap times, and let me tell you that it was hot and tiring out there. It wasn't really my intention to go that fast from the start but I just wasn't paying attention to the pit signboard until about half an hour into the race. I just kept my head down behind the cowl going down the front straight and was trying to keep the front guys in sight. I wasn't trying to race, I was just trying to keep up with them.

Then, when it got harder and harder to still see them. I finally looked up long enough to clearly see the times I was running at. I was astonished and couldn't believe that I was riding that fast. I slowed down but I had already exhausted my energy in the first half of the session, so when I came into the pits, I was just dead.

CW: Can you describe the rest of the race?

Rayborn: Well, it was long. At first there were a lot of bikes and the traffic was pretty bad, but my second session, it wasn’t bad at all. John started and I finished, and we each rode about four hours apiece—with John riding quite a bit faster than I did. Since we were in the top five almost all the way, there was hardly anyone trying to pass us. Instead, we were catching up to and passing slower riders. One time I was passed by Sarron, but he crashed right ahead of me. So I was pretty confident of my pace .

Kocinski: I can only remember being passed by Wayne Gardner on that same bike. It happened after Dominique Sarron crashed the bike and they had repaired it in the pits. Gardner came back out and was just playing around, doing wheelies in front of me, looking at me and waving . . . spinning the rear tire and really playing games. I guess he was trying to pull me along, and it was fun.

He looked over and just shook his head as if to say that he was disgusted after his teammate had crashed the bike, wasting all the hard work he had done. He also didn’t seem to be happy with his teamwork and evidently wasn't being given any pit signals telling him where he stood after the bike spent those 10 minutes in the pits for repairs.

Roberts: That’s pathetic. You don’t put a professional like Gardner out there and then not give him any pit signals. It doesn't matter where they’re at. I'd have just pulled in and said, “Hey, I don’t know what time it is or what’s going on.”

You don’t bring a bike in and work on it for 10 minutes* then send a guy out on it without letting him know where he’s at. How’d you like it, John, if we were to put you out there on the bike while we all just go back to the hotel and have lunch?

CW: What was your race plan?

Roberts: What we were looking for from the guys was consistency; keeping their concentration up at 100 percent while riding the bike at 90 percent. There can sometimes be a concentration problem, and the rider

throws the bike away.

We kept stressing for the guys to keep their eyes on the racetrack, maintaining 90 percent and turning consistent lap times. You have to constantly ask yourself, where is the bike now? You have to keep it on the racetrack and don’t wander. At Suzuka, the heat sometimes makes you think about other things, so you have to consciously think to yourself, how’s the bike? The front tire? The back tire? What’s this or that doing? You force yourself to think all the time.

We just kept driving things in to them because they don’t have the experience. It’s not like with Wayne Gardner . . . with him you can just say, “There’s the bike, go and get on it.” He’s already been through all of it a million times.

To be honest, in their first sessions there were some touch-and-go situations and I was worried, but by the third hour they were doing it right, just like clockwork, so that I was able to quit worrying about them. To be honest, I was feeling the pressure at the start. I was worried about how well they could do. Throwing these guys into what is certainly a big race, an important race, a world event, with a major sponsor, and with my name behind it, was really a bit frightening.

Sure, I was worried, but I can't truly say that they did one thing wrong. I told these guys, “You go out there trying for second place and fall down, and I’m going to kill you. We’re not going to get second place, we want fifth.” And they did it perfectly—better than perfect.

When one of my riders is doing just fine, I want his pit signboard to say “OK.” To me, that means everything is bitchin’. It means that we think what you are doing is great, so don't throw it away, because you will never get that chance again; don’t lose your concentration; don’t try to better it. That doesn’t mean that you should slow down and ride like an old lady, but don’t take any unnecessary chances. “OK” means that everything is cool.

I’m glad to say that we didn’t have any screw-ups, and that’s because they used their heads and did a very, very good job. They were both flawless and I’m proud of them. For me. their personal signboards say “OK.”¡g

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Danforth Problem: Time For Action

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

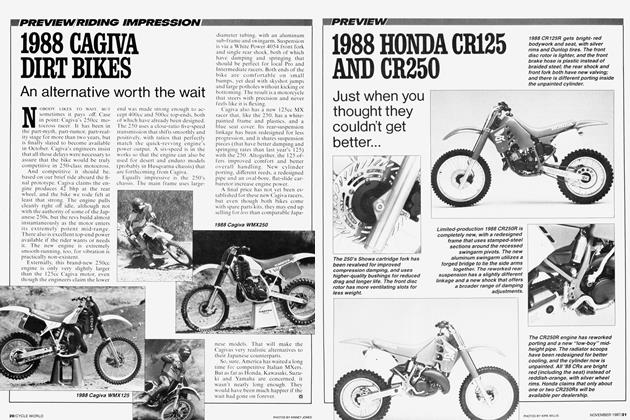

Preview

Preview1988 Honda Cr125 And Cr250

November 1987 -

Preview

Preview1988 Yamaha Yz125, Yz250 And Yz490

November 1987 -

Features

FeaturesThe Bike That Buell Built

November 1987 By David Edwards