TRIUMPH REMEMBERED

Of James Dean, '51 Mercs, Lucky Strikes and Bonnevilles

PETER EGAN

OTHER PEOPLE MAY HAVE GONE into the Big City to shop for clothes or books or records, but on those occasions when my parents made the 80-mile shopping run from our small farm town into the state capitol, I had them drop me off on the outskirts of the city.

That’s where the Triumph dealership was.

Cycles Incorporated was the name of the place, and it was run by an energetic young entrepreneur named Rodney Krunen. When a kid like me, in T-shirt and tennis shoes, walked into the place, Rodney would look darkly over the top of his glasses and say, “Don’t tell me. Lemme guess. You don’t have much money and you’re looking for a nice, clean used Triumph for about $300.’’

He was right, of course. I had no money and that was exactly what I was looking for. Everyone wanted a Triumph then, because in 1965 a Triumph motorcycle was just about the coolest, meanest, neatest thing a person could own. Not before or since have I wanted any material possession as badly as I wanted a Triumph when I was in high school. I was sure that if I could just have one, my life would be complete and all other possessions would be reduced to mere accessories. So I spent a lot of time hanging around Cycles Incorporated, jingling the very small amount of change in my pocket and regarding Trophys and Bonnevilles from their most flattering angles, which seemed to be limitless in number.

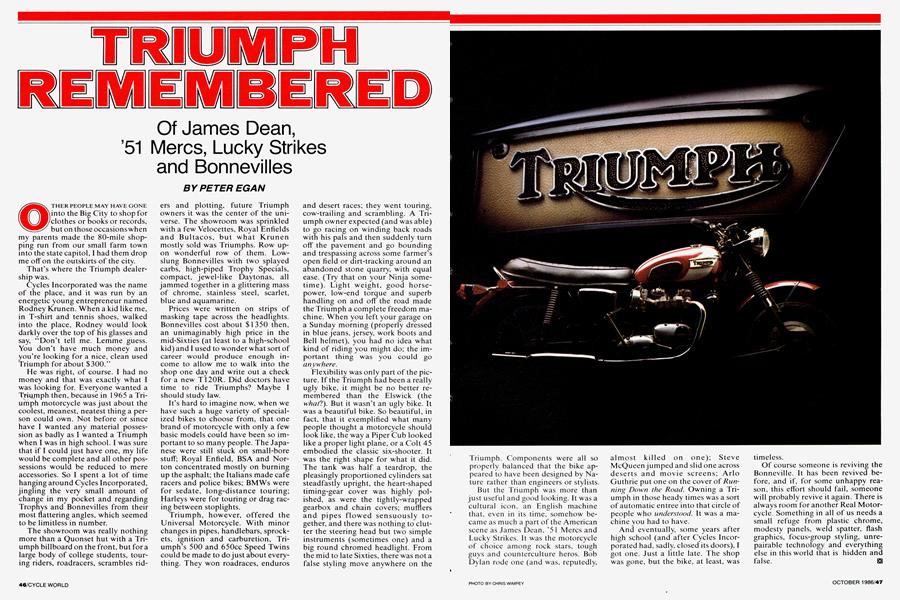

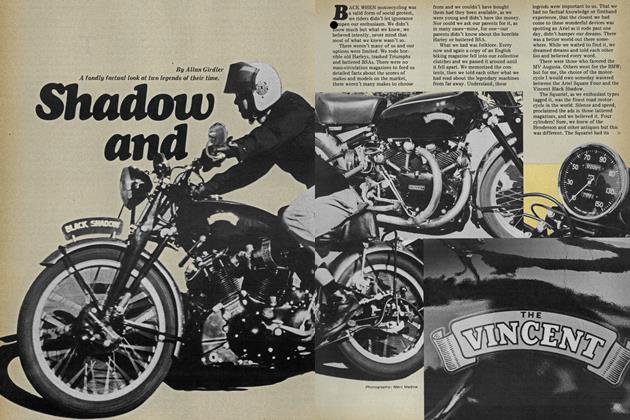

The showroom was really nothing more than a Quonset hut with a Triumph billboard on the front, but for a large body of college students, touring riders, roadracers, scrambles riders and plotting, future Triumph owners it was the center of the universe. The showroom was sprinkled with a few Velocettes, Royal Enfields and Bultacos, but what Krunen mostly sold was Triumphs. Row upon wonderful row of them. Lowslung Bonnevilles with two splayed carbs, high-piped Trophy Specials, compact, jewel-like Daytonas, all jammed together in a glittering mass of chrome, stainless steel, scarlet, blue and aquamarine.

Prices were written on strips of masking tape across the headlights. Bonnevilles cost about $1350 then, an unimaginably high price in the mid-Sixties (at least to a high-school kid) and I used to wonder what sort of career would produce enough income to allow me to walk into the shop one day and write out a check for a new T120R. Did doctors have time to ride Triumphs? Maybe I should study law.

It’s hard to imagine now, when we have such a huge variety of specialized bikes to choose from, that one brand of motorcycle with only a few basic models could have been so important to so many people. The Japanese were still stuck on small-bore stuff; Royal Enfield, BSA and Norton concentrated mostly on burning up the asphalt; the Italians made cafe racers and police bikes; BMWs were for sedate, long-distance touring; Harleys were for touring or drag racing between stoplights.

Triumph, however, offered the Universal Motorcycle. With minor changes in pipes, handlebars, sprockets, ignition and carburetion, Triumph’s 500 and 650cc Speed Twins could be made to do just about everything. They won roadraces, enduros and desert races; they went touring, cow-trailing and scrambling. A Triumph owner expected (and was able) to go racing on winding back roads with his pals and then suddenly turn off the pavement and go bounding and trespassing across some farmer’s open field or dirt-tracking around an abandoned stone quarry, with equal ease. (Try that on your Ninja sometime). Light weight, good horsepower, low-end torque and superb handling on and off the road made the Triumph a complete freedom machine. When you left your garage on a Sunday morning (properly dressed in blue jeans, jersey, work boots and Bell helmet), you had no idea what kind of riding you might do; the important thing was you could go anywhere.

Flexibility was only part of the picture. If the Triumph had been a really ugly bike, it might be no better remembered than the Elswick (the what?). But it wasn’t an ugly bike. It was a beautiful bike. So beautiful, in fact, that it exemplified what many people thought a motorcycle should look like, the way a Piper Cub looked like a proper light plane, or a Colt 45 embodied the classic six-shooter. It was the right shape for what it did. The tank was half a teardrop, the pleasingly proportioned cylinders sat steadfastly upright, the heart-shaped timing-gear cover was highly polished, as were the tightly-wrapped gearbox and chain covers; mufflers and pipes flowed sensuously together, and there was nothing to clutter the steering head but two simple instruments (sometimes one) and a big round chromed headlight. From the mid to late Sixties, there was not a false styling move anywhere on the Triumph. Components were all so properly balanced that the bike appeared to have been designed by Nature rather than engineers or stylists.

But the Triumph was more than just useful and good looking. It was a cultural icon, an English machine that, even in its time, somehow became as much a part of the American scene as James Dean, '51 Mercs and Lucky Strikes. It was the motorcycle of choice among rock stars, tough guys and counterculture heros. Bob Dylan rode one (and was, reputedly, almost killed on one); Steve McQueen jumped and slid one across deserts and movie screens; Arlo Guthrie put one on the cover of Running Down the Road. Owning a Triumph in those heady times was a sort of automatic entree into that circle of people who understood. It was a machine you had to have.

And eventually, some years after high school (and after Cycles Incorporated had, sadly, closed its doors), I got one. Just a little late. The shop was gone, but the bike, at least, was timeless.

Of course someone is reviving the Bonneville. It has been revived before, and if, for some unhappy reason, this effort should fail, someone will probably revive it again. There is always room for another Real Motorcycle. Something in all of us needs a small refuge from plastic chrome, modesty panels, weld spatter, flash graphics, focus-group styling, unrepairable technology and everything else in this world that is hidden and false.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

October 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

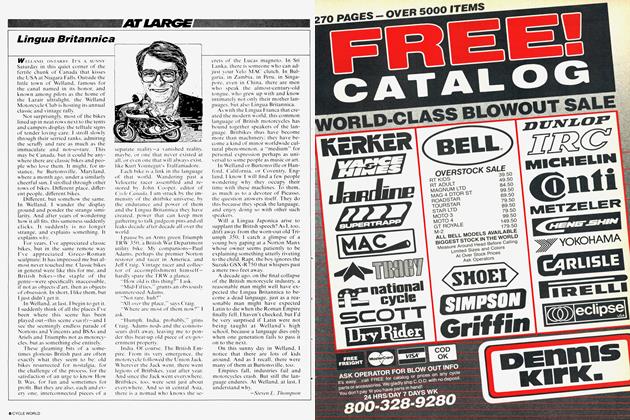

DepartmentsAt Large

October 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1986 -

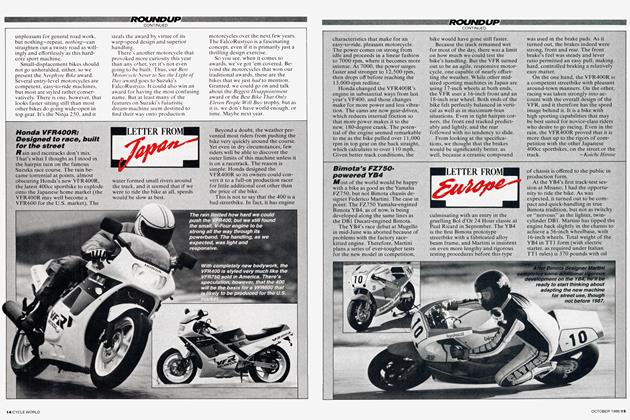

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Ten Best

October 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

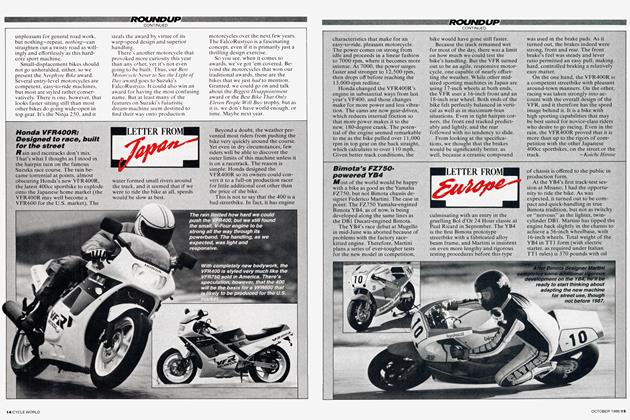

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1986 By Alan Cathcart