AT LARGE

Lingua Britannica

WELLAND, ONTARIO: IT'S A SUNNY Saturday in this quiet corner of the fertile chunk of Canada that kisses the USA at Niagara Falls. Outside the little town of Welland, famous for the canal named in its honor, and known among pilots as the home of the Lazair ultralight, the Welland Motorcycle Club is hosting its annual classic and vintage rally.

Not surprisingly, most of the bikes lined up in neat rows next to the tents and campers display the telltale signs of tender loving care. I stroll slowly through their serried ranks, admiring the scruffy and rare as much as the immaculate and not-so-rare. This may be Canada, but it could be anywhere there are classic bikes and people who love them. It might, for instance. be Burtonsville. Maryland, where a month ago. under a similarly cheerful sun. I strolled through other rows of bikes. Different place, different people, different bikes.

Different, but somehow the same. In Welland, I wander the display ground and ponder the strange similarity And after years of wondering how it all fits, this sameness suddenly clicks. It suddenly is no longer strange, and explains something. It explains why.

For years. I've appreciated classic bikes, but in the same remote way I've appreciated Greco-Roman scu lpt ure: It has impressed me but almost never touched me. Classic bikes in general were like this for me. and British bikes — the staple of the genre—were specifically inaccessible, if not as objects d'art. then as objects of obsession. In short. I like them, but I just didn't get it.

In Welland, at last. I begin to get it.

I suddenly think of all the places I've been where this scene has been played out—this scene exactly—and I see the seemingly endless parade of Nortons and Vincents and BSAs and Ariels and Triumphs not as motorcycles. but as something else entirely.

These gleaming bits of a sometimes glorious British past are often exactly what they seem to be: old bikes resurrected for nostalgia, for the challenge of the process, for the satisfaction of an urge to know How It Was. for fun and sometimes for profit. But thev are also, each and every one. interconnected pieces of a separate realitv—a vanished reality, maybe, or one that never existed at all. or even one that will always exist, like Kurt Vonnegufs Tralfamadore.

Each bike is a link in the language of that world. Wandering past a Velocette racer assembled and restored by John Cooper, editor of Cycle Caucula. I am struck by the immensitv of the Britbike universe, by the endurance and power of them and the Lingua Britannica they have created, power that can keep men gathering to talk gudgeon pins and oil leaks decade after decade all over the world.

I pause by an Army green Triumph TRW 350. a British War Department utilitv bike. My companions—Paul Adams, perhaps the premier Norton restorer and racer in America, and Jeff Craig. Vintage racer and collector of accomplishment himself— hardly spare the TRW a glance.

"How old is this thing?'' I ask.

"Mid-Fifties.” grunts an obviously uninterested Adams.

"Not rare, huh?”

"All over the place.” says Craig.

"W here are most of them now?” I ask.

"Humph. India, probably.” grins Craig. Adams nods and the connoisseurs drift away, leaving me to ponder this beat-up old piece of ex-government property.

India. Of course. The British Empire. From its very emergence, the motorcycle followed the Union Jack. Wherever the Jack went, there went legions of Britbikes. year after year. And since the Jack went everywhere. Britbikes. too. were sent just about evervwhere. And so in central Asia, there is a nomad who knows the secrets of the Lucas magneto. In Sri Lanka, there is someone who can adjust your Velo MAC clutch. In Bulgaria. in Zambia, in Peru, in Singapore. even in China, there are men who speak the almost-century-old tongue, who grew up with and know intimately not only their mother languages. but also Lingua Britannica.

As w ith the Lingua Franca that created the modern world, this common language of British motorcycles has bound together speakers of the language. Britbikes thus have become more than machinery; they have become a kind of minor worldwide cultural phenomenon, a "medium” for personal expression perhaps as universal to some people as music or art.

In Welland or Burtonsville or Hanford. California, or Coventry. England. I know I will find a few' people wondering why they occupy their time with these machines. To them, as much as to a devotee of Picasso, the question answers itself. They do this because they speak the language, and enjoy doing so with other such speakers.

Will a Lingua Japonica arise to supplant the British speech? As I, too, drift away from the worn-out old Triumph 350, I catch a glimpse of a young boy gaping at a Norton Manx whose owner seems patiently to be explaining something utterly riveting to the child. Rapt, the boy ignores the Suzuki GSX-R750 that whispers past a mere two feet away.

A decade ago. on the final collapse of the British motorcycle industry, a reasonable man might well have expected the Lingua Britannica to become a dead language, just as a reasonable man might have expected Latin to die w hen the Roman Empire finally fell. I haven't checked, but I'd be very surprised if Latin were not being taught at Welland's high school, because a language dies only when one generation fails to pass it on to the next.

On this sunny day in Welland, I notice that there are lots of kids around. And as I recall, there were many of them at Burtonsville, too.

Empires fall, industries fail and motorcycles crash. But still the language endures. At Welland, at last, I understand why.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

October 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1986 -

Roundup

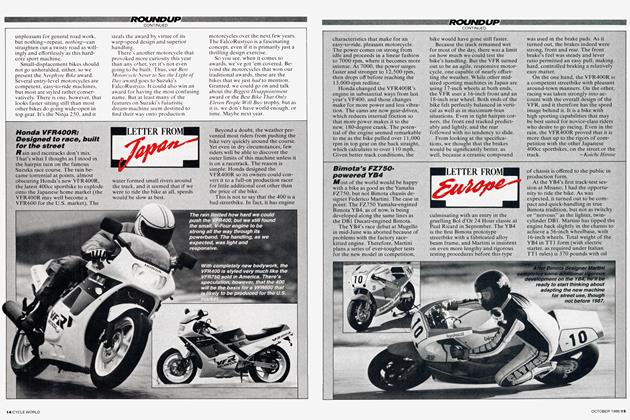

RoundupBeyond the Ten Best

October 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

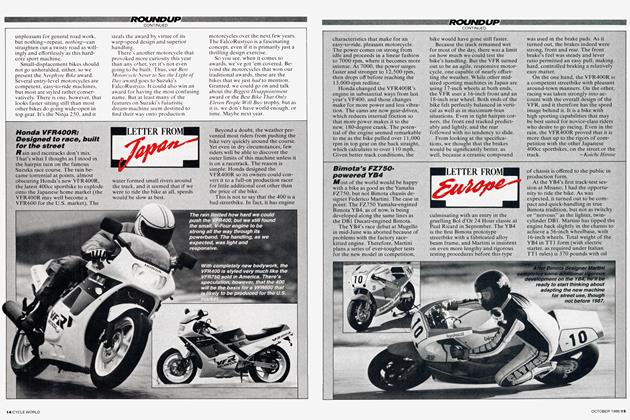

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

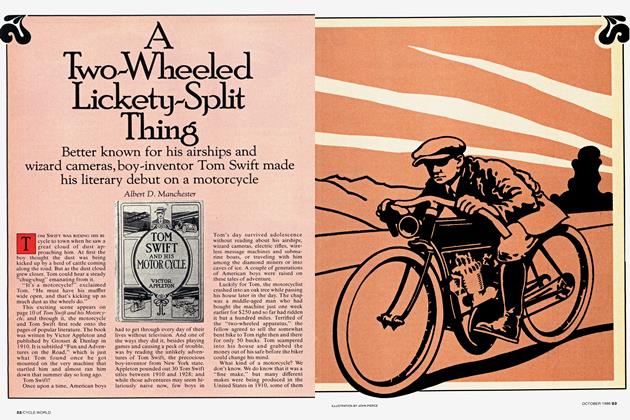

FeaturesA Two-Wheeled Lickety-Split Thing

October 1986 By Albert D. Manchester