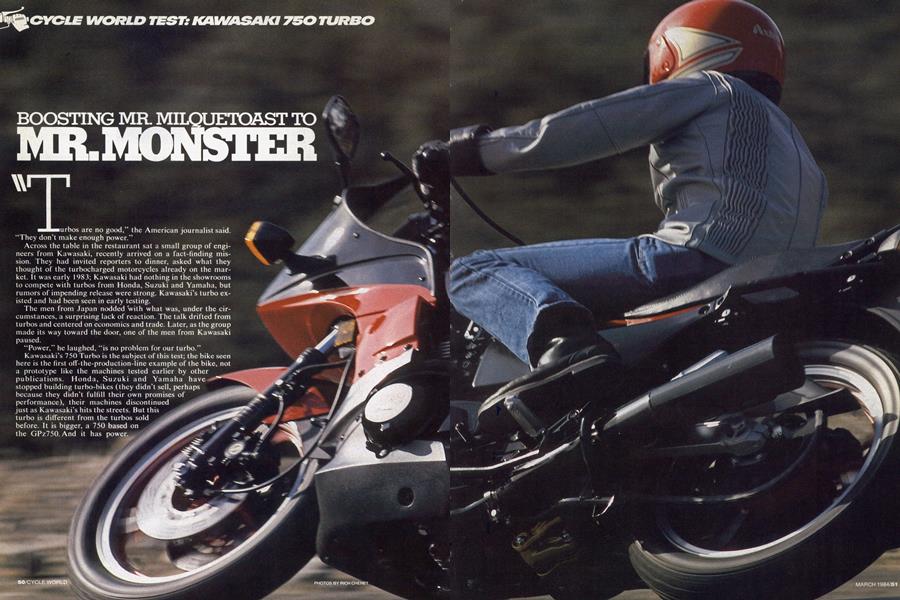

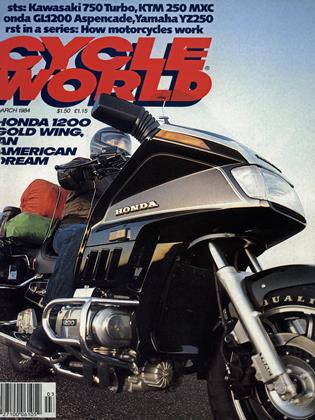

KAWASAKI 750 TURBO

BOOSTING MR.MILQUETOAST TO MR.MONSTER

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

Tlurbos are no good," the American journalist said. “They don’t make enough power.”

Across the table in the restaurant sat a small group of engineers from Kawasaki, recently arrived on a fact-finding mission. They had invited reporters to dinner, asked what they thought of the turbocharged motorcycles already on the market. It was early 1983; Kawasaki had nothing in the showrooms to compete with turbos from Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha, but rumors of impending release were strong. Kawasaki’s turbo existed and had been seen in early testing.

The men from Japan nodded with what was, under the circumstances, a surprising lack of reaction. The talk drifted from turbos and centered on economics and trade. Later, as the group made its way toward the door, one of the men from Kawasaki paused.

“Power,” he laughed, “is no problem for our turbo.” Kawasaki’s 750 Turbo is the subject of this test; the bike seen here is the first off-the-production-line example of the bike, not a prototype like the machines tested earlier by other publications. Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha have stopped building turbo-bikes (they didn’t sell, perhaps because they didn't fulfill their own promises of performance), their machines discontinued just as Kawasaki’s hits the streets. But this turbo is different from the turbos sold before. It is bigger, a 750 based on the GPz750. And it has power. y

Lots of power. Enough power to hurl it through the quarter mile in 11.40 sec. with a terminal speed of 118.42 mph. The numbers aren’t as impressive as those seen in tests of and advertisements for prototype Turbo 750s, and it’s true that the dragstrip used to get those better numbersOrange County International Raceway—is no longer open. But while Carlsbad Raceway lacks Orange County’s traction, the Kawasaki couldn’t have been the fastest and the quickest at any dragstrip. During our testing, the Kawasaki lost its first race against the clocks to a Suzuki GS1150—at the same track on the same day with the same rider.

While not the absolute powerhouse king, the turbo will straighten arms and turn traffic into specks in the rearview mirrors at an astonishing rate. No normally aspirated 750—and few normally-aspirated anythings—can best the turbo Kawasaki’s pressurized acceleration, its headlong rush, its willingness to leap from 60 to 120 mph in what seems like less time than it takes to read this line.

Indeed, power is no problem for Kawasaki’s Turbo.

On boost.

That’s an important qualification, because the Kawasaki, more than any for-sale, mass-produced turbo before, has a split personality. It develops boost at lower rpm than its predecessors and accelerates harder when on boost, and, for just that reason, feels dramatically slower and less powerful when not on boost.

On boost, of course, means that the turbocharger is increasing (or boosting) intake tract pressure above normal atmospheric pressure. All turbos have two chambers and turbine wheels connected by a common, sealed shaft. Exhaust from the engine is routed through the turbine, spinning the shaft. The compressor is mounted on the other end of the shaft, and, as it spins, compresses incoming air and forces it through the intake tract. The compressor must reach a certain rpm before it actually increases pressure; to reach that rpm, the turbine must be powered by enough exhaust gas, which translates to enough engine rpm. Reach that rpm and you’re on boost. Below that rpm, you’re not.

The explanation for the Kawasaki’s boost characteristics lies in the turbocharging system itself and in the modifications made to the GPz750 engine to accommodate turbocharging. The basic engine design is unchanged. This is an air-cooled transverse Four with dohc and two valves per cylinder, a plain-bearing crankshaft, a link-plate primary chain carrying power from the crankshaft to an intermediate shaft, a straight-cut gearset driving the clutch basket off the intermediate shaft, a fivespeed transmission and chain final drive. Many parts found in the Turbo are shared with the GPz750, including the connecting rods, the crankshaft, the cylinder block. The cylinder head comes off the KZ650 with slightly smaller combustion chambers (24cc vs. the GPz750’s 26mm).

The Turbo doesn’t get the GPz750’s hand intake port polishing treatment; boost bikes needn’t rely on such subtleties to make power. The cast threering pistons have thicker sidewalls and are flattopped, not domed, dropping compression ratio from the GPz’s 9.5:1 to 7.8:1 despite the smaller combustion chambers. The head gasket is laminated steel, not the GPz’s asbestos/paper composite (with steel rings around the cylinders.)

Valve sizes and angle are the same as the GPz’s, but valve duration and lift are reduced: intake duration is 32° shorter and exhaust duration is 26° shorter; intake and exhaust lift is 7.5mm, down from 8.5mm. Primary gearing is taller, and first, second, fourth and fifth gearsets have slightly altered ratios because the gears themselves have fewer, larger (and stronger) teeth. The changes raise overall ratios and reduce engine speed at 60 mph from 4400 rpm to 3900 rpm: the Turbo’s extra power allows it to use the taller gearing. The primary shaft damper in the GPz is rubber; in the Turbo it’s a more durable spring-loaded ramp - and - cam assembly. The clutch basket is reinforced and there are eight friction plates instead of seven. Every bearing in the transmission is bigger, and the transmission output shaft is larger diameter, up to 28mm from the GPz750’s 25mm. To discourage detonation, there’s less ignition advance, a maximum of 30° at 3300 rpm compared with the GPz’s 40° at 3600 rpm, and Kawasaki recommends gasoline with a minimum of 90 pump octane.

The line feeding oil to the turbocharger has a filter and the oil pump has 17 percent more capacity than the GPz750’s oil pump. A second oil pump scavenges the turbocharger, keeping oil from building up between the turbine and compressor wheels, seeping past the seals, and burning out the exhaust in a puff of blue smoke—a common problem, especially in the case of bikes fitted with aftermarket turbo kits. To keep the oil cool, there’s a four-row aluminum oil cooler mounted on the downtubes, below the steering head.

Like the GPz750, the production turbo has rubber front engine mounts to reduce vibration and extra frame bracing between the downtubes to compensate for the rigidity lost to the rubber mounts (prototype turbos came with rigid front mounts, without the additional frame bracing).

The Hitachi HT10-B turbocharger is mounted at the front of the engine crankcases, allowing the turbine to be fed by short head pipes and minimizing heat energy lost in the run from the exhaust port. After spinning the turbine, exhaust gases follow a pipe leading around the right side of the cases to the right muffler. Another pipe intersects the first underneath the engine and leads to the left muffler. There’s a small, oiled-foam element air cleaner located under the countershaft cover. Air reaches the turbo compressor through a plenum chamber running under the engine alternator cover, alongside the left frame rail. Compressed air from the turbo is forced through a black-chrome pipe which snakes around the left of and behind the cylinder block to the airbox. Mikuni fuel-injection throttle bodies with 30mm venturis connect the airbox to each intake port.

The turbo has a 47mm turbine wheel and a 50mm compressor wheel and is capable of turning 200,000 rpm. The fastest the turbo ever actually spins is 175,000 rpm. The shaft rides in two onepiece, floating plain bearings positioned between the turbine and compressor wheels. Pressurized oil feeds both the inside and the outside of each bear-, ing shell, and the bearings themselves rotate at about 30 percent of shaft speed, avoiding cooling and lubrication problems.

Maximum boost is 11.2 psi; when intake tract pressure approaches or reaches that maximum, a valve (popularly known as a wastegate) in the turbocharger housing releases exhaust pressure into the exhaust pipe, bypassing the turbine.

A digital microprocessor located in the tailsection controls the Turbo’s fuel injection system: the amount of fuel sprayed into the intake ports depends upon throttle position, engine rpm, altitude, engine temperature, intake pressure and intake air temperature. The injection nozzles and the fuel pump are larger than the nozzles and pump on the GPzllOO. Closing the throttle at low rpm stops fuel delivery to the intake ports, which increases engine braking and fuel economy. Over-rev the engine and the system again cuts off the fuel supply. There’s an over-ride function built into the system so the bike can limp home if a sensor fails, and LEDs on the control box indicate what’s wrong for each component.

The Turbo’s frame is similar to the GPz750’s frame, sharing wheelbase (58.7 inches), rake (28°) and trail (4.6 inches). But there are detail differences designed to make the frame stronger: several tubes are larger in diameter with thinner walls, including the Turbo’s backbone tube, a cross-brace located in front of the engine, and cross-braces above and below the swing arm pivot. The steering is longer, and there’s an extra cross-brace behind it.

Like the GPz, the Turbo has an aluminum alloy box-section swing arm pivoting on needle and ball bearings, with eccentric axle adjusters. But the walls of the Turbo swing arm are 0.5mm thicker.

More power and an unchanged wheelbase can mean a tendency to wheelie; time spent keeping a wheelie under control is time lost in acceleration. On the other hand, lowering a motorcycle and making its suspension stiffer can control wheelies under hard acceleration. That’s why, compared with the GPz, the Turbo has shorter suspension with less travel, a stiffer rear spring, more damping and a new rear shock linkage system (using aluminum struts and rocker arm vs. the GPz’s steel parts) with a more sharply rising rate. The air-assisted forks have 5.1 inches of travel vs. the GPz’s 5.9 inches; rear wheel travel is reduced 0.2 inches to 4.1 inches; seat height is close to 1.0 inch lower. Rear shock adjustments (a fitting for air pressure and a knob to select one of four rebound damping rates) are found behind the right sidecover. The range of damping adjustments is higher, starting at 485 pounds of force at one foot per second piston speed (the GPz’s adjustments started at 400) and ending at 770 (the GPz ended at 660).

The Turbo has an anti-dive system built into the front forks, like the GPz: applying the brakes closes a valve in fittings on the sliders and re-routes fork oil to increase compression damping. The amount of damping increase is adjustable, selected by turning a knob with four positions. The difference is that the amount of damping increase built into the Turbo’s anti-dive system is far greater than the amount of damping increase built into the GPz’s system. In fact, the Turbo’s smallest amount of increase, selected by position one on the adjustment knob, is equal to the GPz’s greatest (fourth position) amount of increase. Which means that the Turbo’s anti-dive does more than make a good line in the sales brochure.

The Turbo’s brakes come straight off the GPzl 100, discs, calipers and master cylinders included. The front discs measure 11 inches and the rear disc is 10.6 inches across (the GPz750 has 10.6-inch front discs and a 10.0-inch rear disc). Like the 1984 GPz750 and 1100, the Turbo comes with new brake lines using a stiffer wall and a Teflon lining. The new lines are less flexible than conventional rubber hoses, which tend to swell when the brakes are applied, reducing power and feel.

The Turbo has the same size cast-alloy wheels as the GPz750, (2.15 x 18 front, 3.00 x 18 rear), and the same size tires (110/90-18 front, 130/80-18 rear). But the Turbo comes with Michelin A48 (front) and M48 (rear) tires instead of the GPz’s Dunlop F17 and K427.

There are other differences setting the Turbo apart from the GPz750: the Turbo’s instrument cluster includes an LCD segmented boost gauge; the forged I-beam handlebar risers are taller, bringing the bars up and back; the front fender is shaped and styled and covers more of the front wheel; the frame-mount fairing extends past the bottom of the gas tank, shrouding the front of the engine, the turbo and parts of the exhaust system. Between the upper and lower sections of the fairing is a sculptured aluminum brace, which bolts between the frame tubes at the forward engine mounts. The brace adds not only to the strength of the fairing but also to the rigidity of the frame by tying together the two downtubes (there’s also a tube welded between the downtubes above the engine mount).

It’s no surprise that the turbo system, the fuel injection, the strengthened chassis parts and the fairing make the Turbo heavier than the GPz750, 552 pounds with half a tank of gas on Cycle World's certified scale, vs. the GPz’s 516 pounds. Offsetting that extra weight is the Turbo’s massive increase in horsepower, 111 bhp at 9000 rpm vs. the GPz’s 85 bhp at 9500 rpm. Where it really gets interesting is comparing the Turbo’s horsepower to a GPzl 100’s horsepower. The GPzl 100 has more peak power, 120 bhp at 8800 rpm, but the Turbo actually makes more power between 3500 and 7200 rpm and more torque between 3500 and 7000 rpm. And the GPzl 100 weighs 578 pounds.

That isn’t to say the Turbo has the low-rpm grunt of a typical 1100, because the GPzl 100 has an a typical big-bike powerband weighted toward high rpm. Compared with a Suzuki GS1100 or Honda V65, the Turbo’s power at 3500 is anemic. Boost starts at just about that rpm, but it isn’t until 4000 rpm that the boost begins to get serious. Above 5000 rpm, the Turbo has enough boost to challenge any 1100 in acceleration, any rider in skill, any motorist in comprehension. It’s the transition from offboost to on boost that’s the biggest thrill of riding the Turbo, the instant change from Mr. Milquetoast to Mr. Monster in the blink of a boost-gauge segment. At 4000 rpm there isn’t much lag between a twist of the throttle and the delivery of big-time, boosted power: above 5000 rpm there is no lag.

The transition to boost works in reverse, too: after boosting past a line of four-wheeled sheep in third gear, upshifting into fifth and dropping below the serious boost mark transforms the Kawasaki into a wimp on wheels. Leaving a traffic light at normal rpm makes the rider wonder where the power went: slipping the clutch is standard procedure as the bike becomes a machine with the weight of an 1100 and the power of a 400.

It isn’t just the power that’s weighted toward high-speed work. The steering is heavy, requiring a surprising amount of effort needed to make a turn. Then there’s the suspension, so carefully tailored to keep the Turbo from flipping over backwards during low-gear, on-boost acceleration. The stiffer rear spring and damping and progression and reduced travel all conspire to send jolts from cracked pavement and potholes and bumps hit at moderate speeds directly to the rider’s spine, without a bit of the sensation lost in the trip. The tires, no doubt selected for Michelin’s reputation as a sporting brand, follow pavement rain grooves at speeds below 50 mph.

The flip side of all that is the Turbo’s performance at extra-legal speeds. Then, with the tach needle edging toward redline, the boost gauge transformed into a spread-tailed LCD peacock, the speedometer needle bending far beyond 85 or 95 or 105 or 125 mph, the stiff suspension and slow steering and wide tire tread pattern all translate into stability. The Turbo is stable at speed, no surprises, no problems. It also has exceptional cornering clearance on both sides, leaving no doubt that this is a motorcycle designed to be ridden hard through turns.

Brakes. They’re excellent at all speeds, requiring just one or two fingers on the front lever to haul the Kawasaki down from any speed close to legal, and, with the help of three or four fingers, dealing easily with any speed the Turbo pilot cares to attain. The brakes are powerful, sensitive, responsive and controllable. They’ll stop the Turbo from 60 mph in 112 feet and from 30 mph in 30 feet.

Not every road is an unpatrolled dragstrip or public racetrack, and getting to roads suitable for prolonged boost usually requires traveling on freeways or toll roads, straight and slow. It’s during those off-boost highway interludes that things like comfort command a rider’s attention. No problem with vibration—bothersome with the prototype Turbos tested elsewhere—because the rubber front mounts do a good job of intercepting same. The seat could be better padded to accommodate riders without natural padding, but it’s not bad. Suspension compliance is biased toward sport.

Then there are convenience items like rearview mirrors, which gain importance as the amount of boost in use increases. For defensive rearward observation, the Turbo’s mirrors are as useless as those on the GPz750 and 1100; unless there’s a Highway Patrol car hidden in the rider’s jacket sleeve—at about the elbow—the mirrors are good only for changing lanes or helping the rider comb his hair after parking and taking off his helmet.

Maybe the Turbo’s cold-starting ability makes up for the mirrors, because this is one bike that doesn’t demand a wait before being ridden away from an over night parking. Flip on the DFI fastidle lever (located on the left-side throttle body, where the choke lever on a set of carbs might be), punch the starter button, and the Kawasaki is running and ready to go. The clutch sometimes squalls a little the first time it’s let out, and drags slightly until the engine warms up, but the Turbo runs and shifts and rolls down the road with no delay.

What we’ve got here is a fast motorcycle with less low-end and mid-range and more top end, a machine weighted toward high-speed use. This Kawasaki is different from bikes equipped with Seventies-vintage aftermarket turbo kits because it makes lots more power, sooner, without routinely backfiring and blowing off the air cleaner cover or collecting oil in the turbine and smoking like a pig or refusing to start. And it is different from the Turbos sold by Honda and Suzuki and Yamaha because it makes lots and lots of power. The Kawasaki has power to spare on boost, and if, off boost, it’s less than impressive, it’s also docile and civilized.

It’s the transition from one half of the Kawasaki Turbo 750’s split personality to the other, the transformation from mild to arm-yanking wild that makes it so exciting.

To the right person, that excitement is worth the price of admission.

$4599

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

March 1984 -

Technical

TechnicalCycle World Follow Up

March 1984 -

Departments

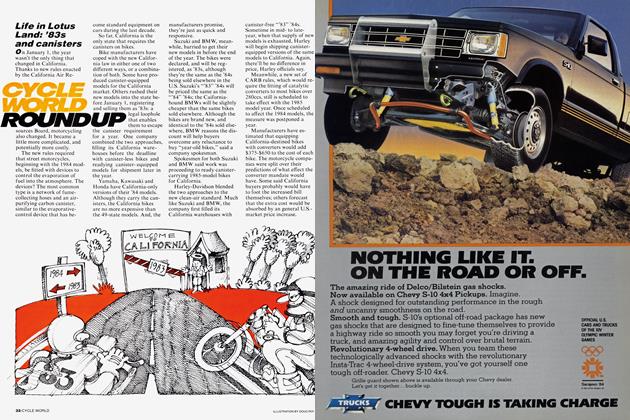

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

March 1984 -

Competition

CompetitionIt's Okay, We're With the Duck

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Special Feature

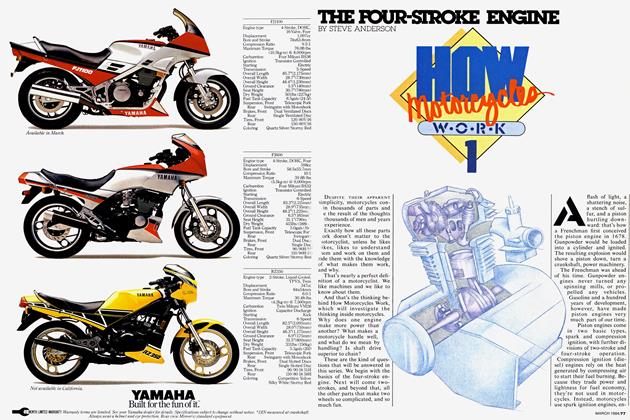

Special FeatureHow Motorcycle W.O.R.K 1

March 1984 By Steve Anderson