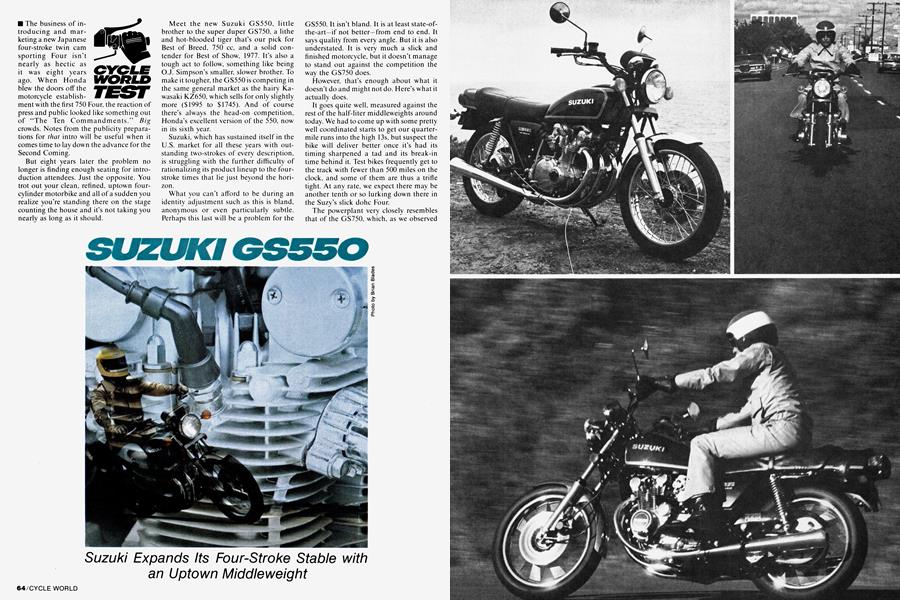

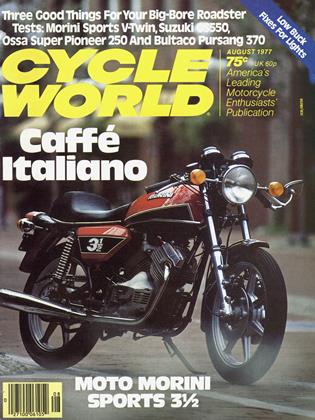

SUZUKI GS550

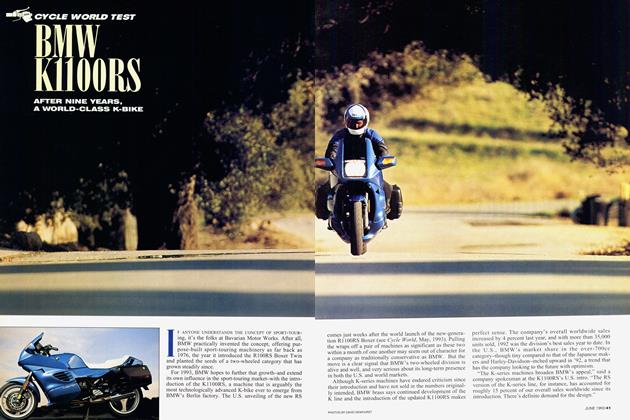

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Suzuki Expands Its Four-Stroke Stable with an Uptown Middleweight

The business of introducing and marketing a new Japanese four-stroke twin cam sporting Four isn’t nearly as hectic as it was eight years ago. When Honda blew the doors off the motorcycle establish-

ment with the first 750 Four, the reaction of press and public looked like something out of “The Ten Commandments.” Big crowds. Notes from the publicity preparations for that intro will be useful when it comes time to lay down the advance for the Second Coming.

But eight years later the problem no longer is finding enough seating for introduction attendees. Just the opposite. You trot out your clean, refined, uptown fourcylinder motorbike and all of a sudden you realize you’re standing there on the stage counting the house and it’s not taking you nearly as long as it should.

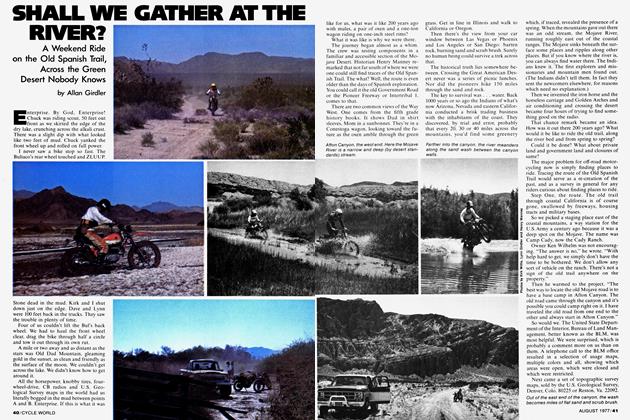

Meet the new Suzuki GS550, little brother to the super duper GS750, a lithe and hot-blooded tiger that’s our pick for Best of Breed, 750 cc, and a solid contender for Best of Show, 1977. It’s also a tough act to follow, something like being O.J. Simpson’s smaller, slower brother. To make it tougher, the GS550 is competing in the same general market as the hairy Kawasaki KZ650, which sells for only slightly more ($1995 to $1745). And of course there’s always the head-on competition, Honda’s excellent version of the 550, now in its sixth year.

Suzuki, which has sustained itself in the U.S. market for all these years with outstanding two-strokes of every description, is struggling with the further difficulty of rationalizing its product lineup to the fourstroke times that lie just beyond the horizon.

What you can’t afford to be during an identity adjustment such as this is bland, anonymous or even particularly subtle. Perhaps this last will be a problem for the GS550. It isn’t bland. It is at least state-ofthe-art—if not better—from end to end. It says quality from every angle. But it is also understated. It is very much a slick and finished motorcycle, but it doesn’t manage to stand out against the competition the way the GS750 does.

However, that’s enough about what it doesn’t do and might not do. Here’s what it actually does.

It goes quite well, measured against the rest of the half-liter middleweights around today. We had to come up with some pretty well coordinated starts to get our quartermile runs into the high 13s, but suspect the bike will deliver better once it’s had its timing sharpened a tad and its break-in time behind it. Test bikes frequently get to the track with fewer than 500 miles on the clock, and some of them are thus a trifle tight. At any rate, we expect there may be another tenth or so lurking down there in the Suzy’s slick dohc Four.

The powerplant very closely resembles that of the GS750, which, as we observed in our test for the January issue, very closely resembles that of Kawasaki’s big street stormers. For all practical purposes, the GS550 is a de-stroked version of the 750, only the tiniest fraction of a millimeter oversquare. Its nine-piece crankshaft turns in six bearings, all but one of the roller variety, and throughout the engine there’s an abundance of ball and roller bearings.

The cam drive gear is centered between the cylinders in the one-piece cast aluminum block, twirling a single roller chaincomplete with Suzuki’s trick self-tensioner—that operates both the overhead camshafts. Like the GS750, tappet adjustment is via insertion (or removal) of round .005-in. shims into (or from) the tappet tops, a task that could be very time-consuming but for the special tool Suzuki has whipped up to allow adjustment without removing the cams (the tool depresses the cam followers).

Everything clicks together slicker than Steve Austin’s bionic arm, and once it’s lit—which is easy, since the GS550 exhibits virtually no cold-bloodedness—this Suzuki Four goes about its business with little muss or fuss, just the precise whirring of the cam chain and not much else. No exhaust note, of course. Five years down the road it’s going to be strange when we’re all riding around on street screamers that don't scream. To anyone raised on big pushrod twins, it’s hard to find joy in the mannerly click and whir of today’s Fours, even when they're swooping through the quarter-mile in 12 or 13 seconds.

Noise or no, though, the GS550 pulls smoothly and evenly, with one up or two. We calculate that the 550’s clicking and whirring delivers roughly 75 percent of the 750's 60 horsepower, and the way this power comes on is where the smaller bike compares least favorably with its larger brother. The 750 seems reasonably civilized until the tachometer needle swings up to about 6000, when the scenery takes a giant leap forward and your eyeballs shorten up by a diopter or three. There aren't any dramatics of this kind tucked away in the 550’s cams or timing. It begins delivering useful power well down in its rpm band—as low as 2000 for ordinary street maneuvers—and continues delivering right on up to the 9500-rpm redline. It’s extremely smooth and businesslike and refined. But if you're waiting for the tiger to jump out of the bushes, a la the 750, don’t hold your breath. The 550 delivers its peak power near the top of its rpm band, but the curve doesn’t include any big jumps. It would be out of character for this machine in any case. Sporting doesn’t necessarily mean muscle-bound.

For all this, the GS550 is only about a second slower than the bigger machine through the quarter—perhaps even less.

The six-speed close-ratio constant mesh gear box gives the engine a big hand in hauling the GS550 through sub-14-second quarters. The ratios are extremely well chosen, and could compensate for an engine with a much more narrow powerband than this one has. However, the gear box itself is a trifle out of step with the snickerysnickness of the rest of the machine. Our test bike was inclined to be somewhat notchy, with a pronounced false neutral between fifth and sixth gears. Finding neutral was a touchy business either at rest or rolling, and all upshifts required a firm toe.

However, the clutch, a wet 14-plate setup, is as sweetly agreeable as most Japanese clutches, and it mitigates the stickiness of the gear box as well as the drive chain, which has a standard touch of slop in it.

There's not much to carp about in the GS550's suspension. It's designed into a package that's very similar to the GS750— with a couple degrees more rake to the front fork, a half inch more trail, and 2.2 in. less wheelbase—and it seems to work just as well, if not better. About the only objection any of our test riders made was to a slight stiffness in the front forks, but this seemed to ease as a bit of the brandnewness wore off the bike. The rear springs and adjustable shocks are exactly right for the solo street rider.

It all adds up to a very sweet-handling machine, as neutral as Sweden and stable as the Deutschmark. The GS550 goes where it’s pointed, sticks quite well on its Bridgestone tires, offers good ground clearance on both sides, and refrains from second-guessing its rider. It handles freeway travel with ease—although if freeways were part of the bike's regular diet, a cog or two more on the top gear wouldn’t hurt. The GS550 does its own version of the Rain Groove Shuffle, which is to say subdued. Like most bikes—and cars, too, for that matter—the Suzy hunts around a bit in the @ #&*%$# grooves, but not to the point of discomfort.

SUZUKI

GS550

SPECIFICATIONS

$1745

PERFORMANCE

FRONT FORKS

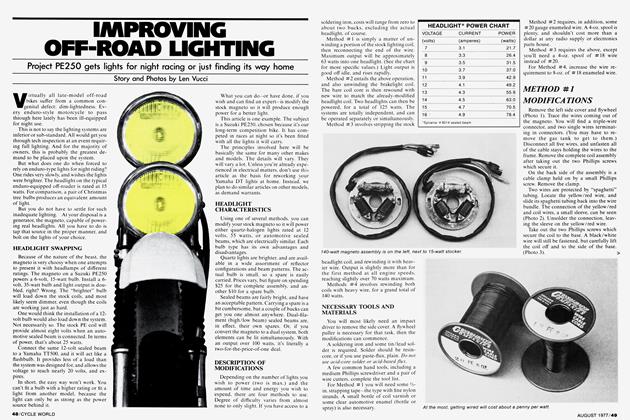

Forks on the GS were slightly stiff, pri marily because of unusually high seal friction, but seemed to loosen as the bike was broken in. Handling can be improved by sealing one of the pair of rebound orifices in each damper rod, thereby increasing rebound control.

REAR SHOCKS

Spring and damping rates are fine for the solo rider who occasionally has a passenger. Converting the bike to a pavement racer would require stiffer damping, and a reduction in spring rate to 90 lb./in. Two-up touring with bag gage would necessitate an increase in sDrina rate, by 10 to 20 lb./in.

Tests performed at Number OneProducts

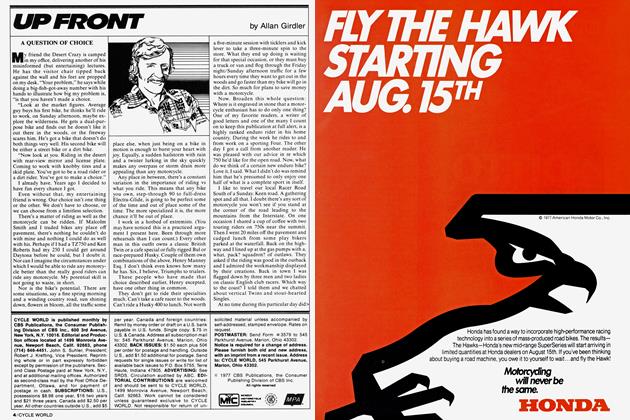

The overall feeling is one of agility and it’s almost surprising to learn that the bike weighs in at 466 lb. ready for test. That's not much mass when you think about chunks like the Honda GL1000, which goes 200 lb. more at least, but the Suzy feels even lighter than it really is.

Augmenting the GS550’s impressive handling is a set of really outstanding brakes. An innocent-looking but surprisingly powerful front disc ( 11,6-in. )/rear drum (7.1-in.) setup, the Suzuki’s binders haul the bike down from almost any speed in remarkably short distances with excellent straight-line control. At the track our Tech Ed got the bike down from 60 mph several times in less than 125 feet, which is outstanding braking in anybody’s book. It requires hard work to produce rear wheel lockup, and the front brake will put up with all sorts of liberties.

Comfort is also a strong point, although one or two riders found the seat a trifle too firm. However, riders who put in a couple laps from Newport to L.A. and back found the seat materials agreeable. Relationship between rider and controls is good and highly adjustable since Suzuki has had the good sense to resist those two-plane seats that seem to be de ri geur on much of today's street machinery. We have a strong feeling those seats are being perpetrated by designers who rarely ride further than the city limits, and would like to mail all of them a copy or two of the Suzuki seats for future homework.

Although the GS550 seems best suited to barnstorming around town or solo sports touring on undulating country roads. Suzuki has put in a touch or two to make the bike suitable for some middle distance touring. There's plenty of room on the saddle for two riders, and the 4.5 gal. tank will support longish hops between pit stops. We averaged 42 mpg on our bike with combined street and freeway use. and expect it to do substantially better than that in a straight cruising situation.

However, before you and your lady set out for the 1977 Artichoke Festival you’ll want to beef up the rear spring rates somewhat. You'll also want to plan your wardrobes carefully. Storage on the GS550 is almost non-existent. There’s a small bin directly under the seat that's wholly occupied by the small-but-adequate tool kit, and there’s a small stuff-space in the little bobtail section mounted just behind the back of the saddle. The latter will hold about half a pair of gloves, a wallet and a sparrow.

Helmet locks also come under the general heading of storage, so we’ll stop here to assess the GS550's helmet lock. It’s terrible. The thing consists of a clip-type spring with a rate that would be better employed in the valve train innards of a diesel locomotive. It is clearly not to be operated by mere mortal hands.

Instrumentation is fairly standard, with a nifty aircraft-style red light behind the display that supposedly makes for easier reading at night. We're not sure whether it does or not. but it sure looks nice. Another slick touch, and almost the only item on the bike that smacks of gimmickry, is the digital gear indicator. Some riders questioned the purity of this last, but in the end it began to look like a Good Thing when one is trying to keep tabs on a six-speed.

The hand grips are reasonably comfortable for extended use and the footpegs are even better, sopping up whatever vibration manages to sneak out of the engine. The passenger footpegs, which look almost as though they’ve been fashioned from some very nice hand grip stock, are also excellent. A particularly nice touch is the rubber inserts in the mirror mounts, which we'd like to see applied industry-wide. It’s very hard to get the GS550’s mirrors to blur at all, although we feel the bike’s super smooth engine deserves a good share of the credit for this vibration-free living.

A rather irritating shortcoming of the controls is the turn signal switch, which lacks a lane change detente and is thus difficult to shut off without looking at. As little as we like beepers, it might be a useful addition to a vague setup like this.

An amusing touch is a vestigial headlight switch. The bike’s ignition is interlocked with the lights, and the switch will not, in fact, do anything, but there it is.

Suzuki’s stylists hit a good formula with the GS750, reduced it slightly to fit the excellent GS400 Twin, and then expanded it somewhat for the GS550. The look is subdued but stylish, with clean, lean lines and plenty of quality brightwork. A nifty little lick up front is a narrow mylar cover for the triple clamps, which makes the whole front look cleaner. The only concession to the cafe look is the little section extending over the rear fender and supporting the big, bright taillamp. In its restrained colors—black and dark forest green—the GS550 is very much the subdued boulevardier, whirring comfortably on its way with so little fanfare that it seldom attracts more than passing attention.

This effect will undoubtedly be welcome to GS550 owners, since so much of the attention that motorcycles attract from the non-motorcycling public is negative. However, it’s not exactly the sort of response Suzuki’s marketing sachems are hoping to produce. And therein lies perhaps the biggest flaw: Maybe this refined, mannerly machine is too refined and mannerly.

The Suzuki GS550 has almost all the attributes of its bigger brother-a smooth, technically up-to-the-minute dohc Four; good looks; excellent handling; outstanding brakes— but lacks the hairy-chestedness that distinguishes the bigger bike from its competitors. It is a machine with any number of solid virtues, but they’re subtle virtues, the kind that take some familiarity to appreciate.

The Suzuki GS550 is definitely short on flash—it almost shuns flash. But it’s extra long on understated substance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue