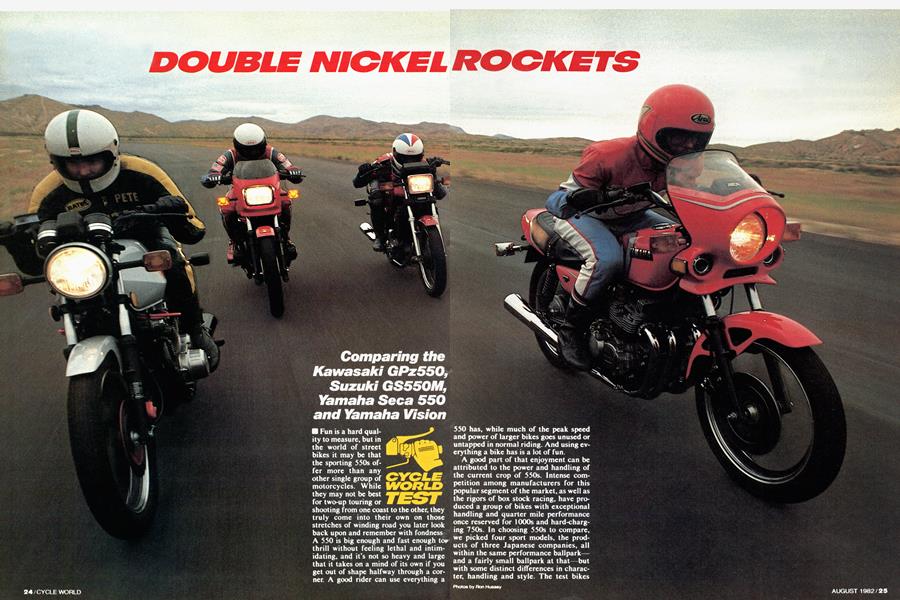

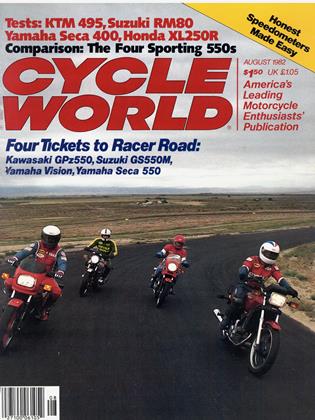

DOUBLE NICKEL ROCKETS

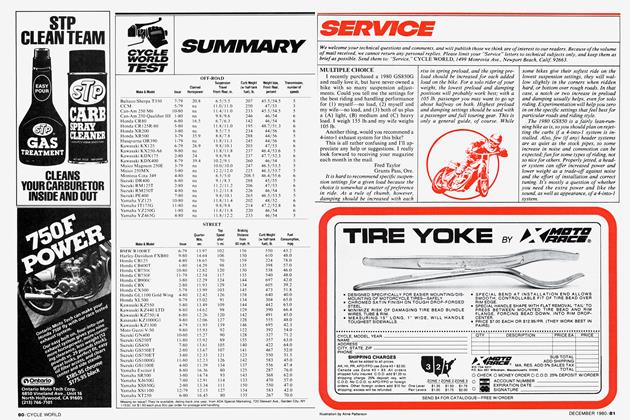

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Comparing the Kawasaki GPz550, Suzuki GS550M, Yamaha Seca 550 and Yamaha Vision

Fun is a hard quaiity to measure, but in the world of street bikes it may be that the sporting 550s offer more than any other single group of motorcycles. While they may not be best for two-up touring or

shooting from one coast to the other, they truly come into their own on those stretches of winding road you later look back upon and remember with fondness A 550 is big enough and fast enough tor thrill without feeling lethal and intimidating, and it's not so heavy and large that it takes on a mind of its own if you get out of shape halfway through a corner. A good rider can use everything a

550 has, while much of the peak speed and power of larger bikes goes unused or untapped in normal riding. And using everything a bike has is a lot of fun.

A good part of that enjoyment can be attributed to the power and handling of the current crop of 550s. Intense competition among manufacturers for this popular segment of the market, as well as the rigors of box stock racing, have produced a group of bikes with exceptional handling and quarter mile performance once reserved for 1000s and hard-charging 750s. In choosing 550s to compare, we picked four sport models, the products of three Japanese companies, all within the same performance ballpark— and a fairly small ballpark at that—but with some distinct differences in character, handling and style. The test bikes

Photos by Ron Hussey

chosen were the Kawasaki GPz, the Suzuki 550M, and two Yamahas, the 550 Seca and the V-Twin Vision.

Of the maior Japanese companies, only Honda is missing from the lineup, which is a little strange because Honda more or less invented the modern 550 class. The old CB, however, has been elevated to 650 status, and the only other Hondas within shooting distance are the FT and CX500s. Both those bikes, however, are aimed at different markets and have little in common with the bikes in the 550 performance class. Honda has a slick-looking dohc CBX550 in Europe now, but nothing yet available for the American market.

One bike almost didn’t make it into the test, and that was the new Suzuki 550M, affectionately known around the office as Katana Jr. For undisclosed reasons Suzuki has directed its U.S. branch not to release the 550M for testing, so we borrowed one from a local owner. The Suzuki, like the Kawasaki, is an updated version of last year’s 550, whereas the Seca is virtually unchanged from last year’s introductory model. All three are inline dohc Fours with chain drive. Only the Vision breaks the mold, with its water cooled 70° V-Twin engine.

In comparing the bikes we commuted to work, took them on weekend rides, ran through a day of track testing at Willow Springs Raceway and rode them to the dragstrip, where each bike was tested for quarter mile times, top speed and braking distance from 30 mph and 60 mph. Strengths and weaknesses quickly emerged, specialties were noted and favorites developed—-all despite the fairly confined performance bracket of the competing bikes. Here’s a rundown on the machines:

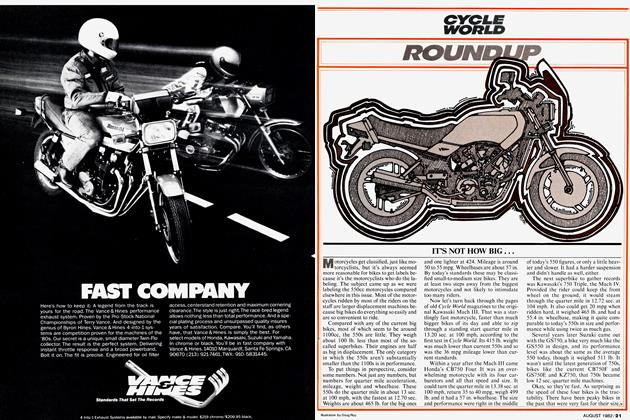

KAWASAKI GPz550

The KZ550 established itself as the fastest way around a roadracing circuit on a Box Stock 550 when it was introduced in 1980, displacing the Suzuki GS550 in that role. Off the track it was also a pleasing bike, with taut handling and midrange power previously unknown to half-liter machinery. In 1981 Kawasaki brought out a more sporting cafe version of the KZ, the Firecracker Red GPz550, with a bikini fairing, low bars and rearsets. Beyond cosmetics, it also got a second front disc, a rear disc in place of the drum, electronic ignition, hotter cams, higher compression, air forks, shocks with adjustable damping and a fuel gauge.

This year’s GPz carries over most of those changes and adds a few more big ones. The 1982 GPz, or KZ550H-1 as it’s known in the parts books, now has an all

new frame with Uni-Trak rear suspension, bigger carbs, a more powerful engine, and a host of smaller changes.

The engine, like the other two inline Fours in this test, has a dohc cylinder head, two valves per cylinder, and drives a chain to the rear wheel. Unlike the others, valve adjusting shims are carried under the inverted cam follower buckets so the cams must be removed to set valve clearances. This year Kawasaki again increased the power on an already powerful engine by redesigning the airbox, increasing ramp speed on the cams, bolting on 26mm TK CV carbs to replace the 22mm TK slide throttle units, and by opening up the intake ports by an extra 4mm. Claimed power on the GPz is now 61 bhp at 9500 rpm measured at the crank, vs. 57 bhp at 9000 rpm last year. Kawasaki says the carbs were changed to improve mileage as well as power.

The GPz’s Uni-Trak suspension is a rising rate system that has more in common with the full-floating suspension on Eddie Lawson’s KR250 roadracer than it does with the normal Kawasaki dirt bike UniTrak. As the swing arm moves upward it compresses the single spring/shock unit from both ends at once. The lower eye of the shock is bolted to the swing arm and the upper end is acted on by a forged steel pivot arm that uses frame brackets for a fulcrum. The swing arm has 5.5 in. of travel and is made of a combination of tube and box-section steel. The swing arm pivots on two separate bolts rather than a single through bolt because the shock moves within the axis of the swingarm pivot. The shock is a non-rebuildable gas-nitrogen type with a free piston between the gas and oil.

There are four damping positions on the shock, adjustable via a plastic

knurled knob at the bottom of the shock, accessible by reaching under the bike, just ahead of the rear tire. You have to get down on your hands and knees to find it, but it’s not hard to reach. Spring preload is another matter. This is adjusted with a threaded collar at the top of the shock, and reaching the collar necessitates removal of the seat, left sidecover, air cleaner and chain guard. These have all been designed for fairly easy removal, but turning the threaded collar from maximum to minimum preload with the shock tool is a laborious process requiring dozens of strokes of the wrench in tight quarters (tight meaning knucklebusting).

Despite all the new hardware the new GPz weighs 1 lb. less than last year’s, even with more gas aboard in the new 4.7 gal. tank, almost a gallon more than last year’s 3.8 gal. container. More plastic parts have been used—battery box, rear fender, seat pan, etc.—and larger diameter but thinner wall tubing has been used in the frame.

Wheelbase has also increased, to 57 in. from 54.9 in., mostly as a result of the Uni-Trak system, and the front end has been kicked out an extra 1.5° with an extra 0.4 in. of trail to slow down the steering. The steering head now uses tapered roller bearings.

Other changes include a straight-pull throttle, dogleg brake and clutch levers, tinted mirrors and a new LCD instrument panel with a battery level sensor, sidestand warning light, and a gas gauge that has a disappearing row of little LCD blocks to show fuel level. The new fivespoke wheels, which weigh the same as last year’s seven-spoke wheels but look lighter, are painted a bright red, as is the swing arm. Handlebars are modular, with cast aluminum uprights and non-adjustable steel tube ends.

List price on the GPz is $2749.

SUZUKI GS550M

When introduced in 1977, Suzuki’s GS livened up the 550 class by rediscovering some of the power and speed lost to Honda’s 550 Super Sport as it became gradually slower and heavier. The Suzuki was fast, and could be made reliably faster, and it could also be enticed to handle well with a little fork oil and shock treatment. Since then the bike has gone through a number of styling apd detail changes, but the same basic engine is with us still in the new Katana-style GS550M.

The biggest mechanical change to the engine in five years has been the substitution of 32mm Mikuni CV carbs for the original 22mm Mikuni slide throttle units. It is a dohc inline Four with a bore and stroke of 56 x 55.8mm and a compression ratio of 8.6:1. The camshafts are driven by roller chain, the crank rides on roller bearings and drives the clutch with straight-cut gears, and it has a six-speed transmission.

If the engine hasn’t changed much, the styling and chassis certainly have this year. The new GS has received the full Katana treatment; not quite as radical as the Katana itself, but more clearly in the same mold than the GSI 100E. The seat is sculptured in orange and black, rising to meet the top curvature of the huge 6 gal. silver gas tank. The angled sidecovers bear the Katana sword emblem and the front fender is finished off in silver and black. Rear springs, brake calipers, brake hubs and spark plug wires all stand out in bright orange. The goodlooking engine remains visible and silver, but the exhaust system is plated with black chrome.

Functionally, the bike now has air forks and four way adjustable damping on the rear shocks. The Suzuki’s triple disc brakes, with big 10.7 in. brake rotors, provided 275 sq. in. of swept area, the largest in the group by 65 sq; in. Tapered roller bearings are used in the steering head and the swing arm moves on needle bearings. The choke lever is now thumb operated at the left grip rather than in the

middle of the steering head, as is true of most other Suzukis this year.

Instrumentation on the Suzuki is simple and clean, with a pair of round faces for the tach and speedo, with a set of warning lights and a needle-type fuel gauge in the middle. At 475 lb. with half a tank of fuel, the GS is by 13 lb. the heaviest bike of the group, the Yamaha Vision being next at 462 lb. Part of that weight, of course can be attributed to the larger gas tank. The 57.5 in. wheelbase makes it also the longest of the group by a bare 0.5 in. over the Vision and the GPz. Handlebars are tubular steel type.

The Suzuki carries the lowest suggested list price in the group at $2599, $60 less than the Seca and $350 less than the most-expensive Vision.

YAMAHA 550 SECA

Yamaha’s Seca was a brand new design last year, and this year’s model is completely unchanged except that it is now painted red with white trim instead of the other way around. The Seca is the shortest and lightest bike in the group, with a 55.3 in. wheelbase and a test weight of

424 lb. That’s 35 lb. lighter than the next lightest bike, the GPz.

The 528cc engine also has the smallest displacement in the group, and it’s the narrowest of the Fours. The Seca engine belongs to the XS11 design group, though considerably scaled down from that powerplant. It is a dohc inline Four with two valves per cylinder and roller chain driven cams. Valves are adjusted with shims that ride on top of inverted buckets under the cam lobes. The crank rides in plain bearings and drives a Hy-Vo chain to a jackshaft behind the cylinders. This shaft drives both the clutch and the a.c. generator, which are tucked in behind the engine to keep it narrow.

Four 28mm Mikuni CV carbs feed the engine, and the cylinder head uses Yamaha’s patented YICS (Yamaha Induction Control System). YICS is sort of a small manifold or holding chamber cast into the cylinder head. It holds part of the fuel/air mixture between power strokes of the engine and when the intake valves open allows part of the mixture to be drawn into the valve area through subports. The small diameter of the subports increases the velocity of the incoming mixture and aids in the swirling of the mixture, while promoting better burning and lower emissions.

The Seca has a single 11.7 in. disc brake at the front and a drum at the rear, with an adjustable front brake lever. Front suspension is non-adjusiable for damping and comes without air caps; the two rear shocks have six spring preload positions but no adjustment for damping.

Tucked inside the small fairing is an instrument cluster that includes a tach and speedometer, needle-type voltmeter and fuel gauge and a small row of idiot lights. The fairing itself is a bit larger than the Kawasaki’s. Handlebars are conventional tubular type.

Suggested list is $2659.

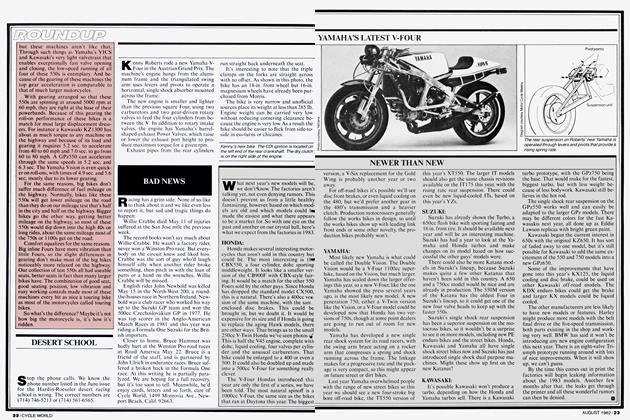

YAMAHA 550 VISION

The Vision is easily the most unusual bike, mechanically speaking, of the test. Introduced this year, it has a 70° water cooled V-Twin engine. The engine is highly oversquare at 80 x 55mm and has two chain driven cams in each of its fourvalve cylinder heads. The crank spins in the same direction as the wheels, on plain bearings, and operates a gear-driven counterbalancer at the front of the vertically split cases. The clutch is driven by a straight-cut gear off the crank. A pair of 36mm downdraft carbs sits between the cylinders and feeds the engine through ports connected to the Vision’s own YICS system. This uses a V-shaped plastic mixture reservoir that hangs between the cylinders on the right side. An aluminum radiator is bolted to the front of the frame, using an electric, thermostat controlled fan that pulls air through the radiator when traffic slows down.

The Vision’s chassis is also the most unusual of the group. It uses a “hang support’’ frame with a narrow, triangulated backbone whose lowest tube runs along the tops of the cases. Most of the engine is suspended below the frame tubes. Rear suspension is Yamaha’s Monoshock design, with the top of the shock bolted to the frame beneath the seat. The triangulated swing arm upper pivot pushes directly against the lower shock eye, and the shock is in a laid down, almost horizontal position.

The Vision is the only bike in the group with shaft drive, the enclosed shaft forming one side of the Monoshock swing arm. The shaft side of the rear hub incorporates a 7 in. drum. The front brake is a single 11.7 in. disc. Front suspension is non-adjustable without air caps and the single rear shock has five spring preload

positions, set by raising the seat and turning the collar with a shock tool. Damping is non-adjustable. The front fork is kicked out to provide turning clearance at the radiator, so the fork ends have trailing axle clamps to retain normal rake/trail dimensions.

In dimensions the Vision is at none of the extremes. Its 57 in. wheelbase is about the same as the GPz’s and the GS550’s, it’s the second heaviest bike at 462 lb, only 3 lb. heavier than the GPz, and it has the third largest gas tank at 4.5 gal. It is, however the lowest geared bike, turning 5295 rpm at 60 mph.

While instrumentation is contained in a styled rectangular module, it is fairly simple, with a speedo, tach, water temp gauge and idiot lights. The handlebars are four piece modular units where the upright piece on either side forms the outer clamp on the fork tube at the top of the triple clamp and the other end holds the round handgrip piece. The uprights are of forged aluminum and the handgrips are steel with splined insert ends to allow a small amount of angle adjustment.

With a suggested retail price of $2849, it is the most expensive bike of the group, $100 more than the next-expensive GPz.

PERFORMANCE

KAWASAKI GPz550

In measuring performance we usually think of acceleration and speed first and then handling, but the word encompasses both areas, without regard for comfort and other amenities. In this test the Kawasaki GPz won the high-performance nod without much trouble. During our day at the drag strip it turned a best quarter mile of 12.70 sec. at 102.04 mph and, good run or bad run, made all of half a

dozen runs in the sub-13s. We had managed to get both Yamahas into the high 12s during previous tests, but on the day of testing were unable to get any time faster than a 13.06 sec. at 96.87 mph for the next fastest bike, the Seca. So the Kawasaki was almost .4 sec. and about 4 mph quicker and faster than the next in line. Terminal speed in the half mile radar run was 116 mph, 5 mph faster than the second place Seca with 111 mph. The only faster 550 around is last year’s GPz, which managed a .05 sec. and 2 mph advantage over the ’82 we used in this test.

If the Kawasaki was the fastest bike in a straight line, it also proved to be the easiest and most predictable bike to ride fast around the race track. The Kawasaki and the Vision are very close in their handling capabilities, but right out of the box the GPz provides more adjustability to rider and track demands as well as a higher level of confidence inspiring stability in both fast and slow corners. The bike feels taut, responsive to rider input and is less affected by bumps and extraneous surface changes. The tires stick well with no sudden surprises, and share with the other three bikes a rating of excellent—especially by OEM tire

standards.

The GPz required a little more muscle in fast right-left-right transitions than both Yamahas, but that is partly because of its good straight line stability. With a bit more air (14 psi) than the 10 psi recommended in the front forks, the GPz also demonstrates excellent resistance to dive under very heavy braking. The adjustable damping and wide range of spring preload in the rear also allow the bike to be set up for good cornering clearance and suspension compliance for a variety of riders.

For fast street riding and even a moderate amount of race track flogging the single rear shock works fine. But some road racers have found the shock can fade under hard use, particularly in hot weather or when oversize tires are used. For those conditions some racers have installed remote reservoir nitrogen-charged shocks, along with stiffer front springs. On the street, however, the GPz works about as well, out of the box, as anything unleashed on the public, and such changes are unnecessary.

Besides speed and handling, the GPz also provides a virtually bulletproof clutch. The bike was easiest to ride at the dragstrip because of the consistant, even clutch engagement, which did not change after many runs.

A number of good riders have done well at the race track on Yamaha Visions, but skill has been an important factor here. For consistent, willing bank-on-it performance, the red Kawasakis are still the fast way down the strip or around the race track.

YAMAHA 550 SECA

When we first tested both bikes, the Yamaha Vision was a few hundredths of a second quicker than the Seca and .2 mph faster. In handling, the Vision felt slightly more stable in fast corners and had a little more drive coming off corners. While imparting totally different riding sensations, both bikes were within a hair’s breadth of one another, the slight edge going to the Vision.

In this test the balance slipped the other way, possibly because the Vision had several thousand more miles on it than the Seca. In any case, the Seca edged out the Vision at the drag strip, turning a 13.06 sec. at 97.82 quarter mile, vs. 13.09 sec. at 96.87 for the Vision. Those times are so close as to be virtually identical, and may in part reflect a problem of slightly vague clutch engagement with the Vision. Those times would have qualified both bikes as genuine superbikes a few years ago and are fast 550 runs. The Seca also pulled out a bare 1 mph on the Vision in the half mile, at 1 1 1 mph.

The Seca also slipped ahead in race track handling. While the front forks felt 'moderately soft and the footpegs felt farther forward than the other bikes in the test, giving the bike a slight hobby horse feeling over bumps and under heavy braking, the Seca managed to get around the track smoothly and quickly. No serious wobbles in fast corners, no problem with quick transitions and no ground clearance problems, considering both stands were left on the bike (and on all of the bikes).

What makes the Seca different from the other bikes is its small size. It is noticeably smaller and lighter feeling than the others, more like the 400 it grew out of than a reduced 650. This makes it nimble and quick steering. The short wheelbase also causes it to be just a bit more twitchy in fast going and and the rear brake can make it wiggle a little, but it’s fun to ride at speed because it changes direction so well. Twitches and wiggles stay small and minor, never escalating into the kind of wobble that makes you slow down or back off the throttle.

Despite having a single front disc and a rear drum, the Seca shares braking honors with the Suzuki GS550M, both bikes

stopping in 128 ft. from 60 mph. Though the rear brake sometimes locked up a bit more easily than expected until the rider was used to it, the bike stopped straight and without drama. Slightly stiffer front springs would have made it feel even better, removing some of the dive and feeling of front end vagueness under race track braking. Shifting was good enough to escape notice, and missed gears were never a problem.

YAMAHA 550 VISION

As mentioned, the Vision lost out on its older but smaller brother, the Seca, by almost insignificant margins at the drag strip, turning a 13.09 sec. at 96.87 mph quarter mile. Not far behind, but still behind. The Vision ran through the half mile radar trap at 1 10 mph, 1 mph slower than the Seca and 6 mph slower than the GPz.

Slim fractions of seconds at the drag strip would not be enough to put the Vision in third place for performance if the bike’s handling were significantly better than the Seca’s—or the Kawasaki’s. But we could not get the Vision to handle as well as our original test bike did when it was brand new. Straight line stability was excellent with the Vision, and it handled well in tight corners, heeling over easily and holding its line with minimal steering input. But on fast bends like Willow Springs’ Turn Eight the bike developed a shuffling wobble over bumps and road irregularities. Jacking up the rear spring preload helped somewhat, but didn’t entirely eliminate the problem. There is no damping adjustment to either end of the suspension, so we couldn’t experiment with more or less damping. Most of this back end motion was no doubt due to the condition of the rear tire, which was pretty well squared off, apparently by previous drag strip runs and track testing. A new rear tire would probably have returned the unshakable high speed stability we enjoyed in the test bike of our May, 1982 road test.

The Vision has plenty of ground clearance and could be ridden hard on the street without any sign of handling problems, even with the rear tire worn.

An assessment of performance should include street capabilities in real riding situations as well as ultimate perfor-

mance figures from the track, and on the street the Vision has one virtue that shines. That is roll-on power. The highly oversquare Twin beats even the GPz in contests of passing speed from 50 to 70 mph, though by a very small margin. More importantly, it feels fast, giving the bike a pleasant sling-shot sensation, like a true Twin, when the throttle is rolled on from moderate speeds. Out on the track, peak power has it doing close battle with the GPz and the Seca, but nothing feels quite as exhilarating as the Vision accelerating out of pit row—or out onto the highway from a roadside cafe.

Brakes on the Vision were rated least favorite of the group, mainly for vagueness, vs. the more easily modulated, firm feel of the others, particularly the GPz and Suzuki. Shifting on the Vision is first rate, and clutch and throttle pull are light.

SUZUKI GS550M

The Suzuki landed at the bottom of the performance pile mainly for what one test rider called its “imitation carburetor substitutes.” The 32mm Mikuni CVs, as they come from the factory, provide borderline unacceptable carburetor response on the 550 engine. It takes five to ten minutes of engine warmup and riding on choke before the carbs begin to work their best, which isn’t any too good. Unless the engine is revved very high off the line, the bike will gasp and falter, faking out the traffic behind you at the stoplight. Rolling on a handful of throttle at any speed has the opposite of the intended effect, i.e. it slows the bike down, leaving it bogged in an immense flat spot. It is actually possible to kill the engine in a slow, tight corner by whacking open the throttle.

Our best drag strip time on the GS was a 13.93 sec. at 94.04 mph, with 107 mph recorded through the half mile radar. That was our only pass that broke out of the low 14s, and it was accomplished when our test rider, out of desperation, used half choke for the run.

All this would be a bit depressing, except for one thing. The carb problem is easily solved. We had similar rideability problems on the Suzuki GS450 last year and cured them by swapping two washers around on the carb needles, effectively raising them to provide a richer mixture. The GS550 carbs are identical in design, so we tried the same washer switch and it worked. With the needles raised the choke can be switched off after a short warmup, the stumble is gone off the line and there is no staggering flat spot when the throttle is twisted open at any speed. The bike is still slower in roll-ons than the other three 550s, but slowness here is a relative term and the bike is a pleasure to ride.

This is not a fix Suzuki can make, nor is >

it a modification your dealer can legally perform, but an owner can raise the needles easily with no more than a phillips screwdriver and a pair of long-nosed circlip pliers to remove the needles from the carb pistons. The entire job takes about 20 min. What is hard to understand is why Suzuki is selling the bike in this condition. All the other manufacturers have managed to get exemplary throttle response out of their 550s, while the GS Suzuki has had carb-related running problems since the switch was made to CV carbs two years ago. There are, at least, rumors of a revised 550 engine in Suzuki’s future, so maybe the problems will be ironed out.

The carb glitch and lack of horsepower are the only real problems in a bike that is otherwise very nice to ride. Out on the race track the GS has a firm, mechanical feel that is pleasantly reminiscent of the bike’s larger role model, the 1000 Katana. Steering is light and precise, the triple disc brakes are the best of the group, both in power and effortless modulation, and the bike shifts flawlessly. If the air pressure in the front forks is allowed to drop even slightly below the recommended 7.1 psi, the front end dives considerably under heavy braking. It feels best with about 10 psi in the tubes, and the dive problem goes away. The only intrusion upon the bike’s excellent cornering stability is ground clearance. The problem is hardly noticeable on the street, but on the race track the exhaust pipes and/or side and centerstand will throw up a shower of sparks long before the footpegs touch down, so the sound of grinding metal is a signal to slow down. The Suzuki has the poorest cornering clearance of the group. That, together with troublesome throttle response and an engine that simply isn’t producing horsepower on a par with the other three bikes, puts the GS at the bottom of the performance list.

COMFORT AND UTILITY

YAMAHA 550 SECA

In our collective assessment of the bikes, the Seca narrowly edged out the GPz in the comfort and utility rating,

which in turn barely came out on top of the Vision.

Reasons? The Seca starts up well cold and warms up quickly enough to be handy for short trips and running errands. Once warm, it has a light, jaunty feel and a spirited, cammy engine with a nice, muted snarl. Yet despite it’s upper end rush, the engine still manages a respectable amount of pull from lower rpm. The Seca has the smallest gas tank of the group and got roughly the same mileage as the others in city/highway driving, yet the mileage was least affected by hard, fast riding. When the others dipped into the mid to high 40s on a group ride up the mountain pass, the Seca’s mileage remained in the mid 50s. In short, the engine works well and it’s fun to use and listen to.

The Seca is one of two 550s with a small fairing, but unlike the GPz’s small screen, it actually affords a modicum of wind protection, taking some of the fatigue out of highway trips. Seating position on the Seca was the most controversial part of its comfort rating. Shorter riders found it perfect, and taller riders wished the pegs were farther back, keeping the knees farther away from the handlebars. Of all four bikes, the Seca has the most chair-like seating position, which some liked and some didn’t as a matter of personal preference, but no one found it uncomfortable out on the highway. In the Seca’s favor, it comes with those marvelous anachronisms, the cheap, adjustable, readily-replaceable, available-everywhere tubular handlebars. The Seca’s bars were comfortable for nearly everyone, but if you don’t like them you can do something about it.

Suspension on the Seca is not adjustable except for preload on the rear springs. This made the bike feel a bit softer and looser than others on the race track, but in everyday riding provides comfortable riding over a variety of road bumps. For a bike with light weight and a short wheelbase the Seca also handles regular timed bumps, such as expansion strips, fairly well without a lot of hobby-horsing.

Servicing procedures are fairly straightforward on the Seca. It has shims on top of the buckets, so a valve adjust can be done without tearing the top end down. Other

than that, the chain needs to be oiled and the engine oil changed at normal intervals. If you carry a passenger and want more spring preload, the two external shocks can be quickly adjusted with the end of a screwdriver.

Instrumentation includes a voltmeter and a fuel gauge, with a row of warning lights between the tach and speedometer. Turn signals are self-cancelling and all the handlebar controls are easy to use and to find.

KAWASAKI GPz550

The GPz550 is an improved road bike this year, thanks to the changes in the rear suspension. The longer wheelbase, along with the rising rate single shock, has given the back of the bike a more compliant and comfortable ride. Some of the quick, darty nature of the bike has been sacrificed, but the suspension handles repetitive road shocks better than before. The only drawback to this suspension, as mentioned, is that adjustment is a relatively tedious and time-consuming operation. A wide range of adjustment is fine if it’s easily done, but we suspect a lot of owners are going to preload the rear spring where they want it and then leave well enough alone. No one wants to stop by the roadside and remove the seat, lift the tank, remove the air cleaner and the chain guard and make fifty or sixty strokes of a wrench in cramped quarters just so he can change the preload a few notches.

Few riders of our acquaintance have ever complained that the five or six spring preload cam positions on a conventional shock offer too little range of adjustment and that more intermediate positions are needed. Canyon racers who like to play with their suspensions may enjoy this feature, while most riders will probably leave it alone.

The fairing on the Kawasaki provides about as much wind protection as a small tank bag or a very large headlight, and is there mostly for looks. It keeps the rain out of your lap, however, and cuts down on the wind below mid-chest level. Handlebars on the GPz are of the four-piece separate casting and handgrip type and are not adjustable or replaceable with tubular bars. This could be more of a problem than it is, as Kawasaki has worked out a handlebar position that seemed to fit all of our test riders fairly well, without causing any discomfort or complaint. Footpegs are rearset, the seat is comfortable and most of the test riders agreed the riding position felt good, except for one who mentioned that the tank felt too wide at the rear, forcing his knees outward.

The Kawasaki starts easily with full choke, operated by a knob at the left side of the carbs, unlike the other three bikes, with left thumb levers, and takes only a little longer to warm up and run off-choke than the two Yamahas. After that throttle response is excellent and the bike has

enough midrange torque and top end power to make it equally at home idling around town or moving out and passing cars on a fast stretch of two-lane. The big 4.7 gal. tank is good for 200 to 250 mi. without a fuel stop, which also makes the bike a good choice for a solo tour.

Instruments, other than a normal tach and speedometer, include an automatic check list warning light panel with a red light that blinks if something is wrong (sidestand down or battery low, for instance) and an LCD fuel gauge with a stack of nine little boxes that disappear along with the fuel. The bottom box blinks when the bike is low on fuel. The left handlebar cluster houses a horn button with a huge thumb lever, turn signal switch, a rocker switch for hazard lights and a high and low beam switch for the headlights. That’s a lot of choices, and you often end up hitting the long horn lever when you’re looking for something else, usually while passing a police car.

Maintenance chores on the GPz are fairly normal except for valve adjustment, which requires removal of the cams. This operation is beyond the ability of some owners to perform, and as adjustment is seldom needed, most people will have it done at the dealership. Unfortunately, some of our Service mail indicates that a percentage of these valve adjusts are also bungled by mechanics who get the cams in wrong. This job is more complicated than it has to be, and all of the other bikes use easily removed, if heavier, valve shims on top of the valve buckets rather than beneath them. In balance, of course, they don’t turn 12.7 sec. quarter miles.

In short, the GPz is a comfortable, useable bike for almost any on-road type of riding, and it gives the comfort and utility edge to the Yamaha Seca only in having a less useful fairing and more involved adjustment procedures for the valve train and the rear suspension.

YAMAHA 550 VISION

The Vision might easily have been the hands-down winner in comfort and utility, except for one problem, and that is its handlebars. The bars work fine around town and even on the race track when the rider is crouched, but out on the highway in a 55 mph (and up) wind they force the rider to do a constant pull-up while leaning into the wind. We’ve had lots of other bikes

with bars we didn’t like, but we could always replace them. But the Vision’s handlebars have forged aluminum uprights that form the outer halves of the upper triple clamps and are an integral part of the bike. The handlebar ends are splined and adjustable for wrist angle, but lack enough adjustment to change the riding posture. Also, the aluminum is soft and the steel ends are hard, so great care must be taken when making adjustments not to damage the tiny splines. Like the Kawasaki’s rear spring, it’s best to get the adjustment where you want and leave it there.

A fairing would help reduce wind pressure on the rider and make the bars more comfortable at high speed, but the unusual bars, as well as the rectangular headlight and instrument module, may limit the number of aftermarket fairings that fit the bike. The handlebars are a part of the bike’s angular styling, and in this case style takes precedence over simplicity and utility.

Beyond that, the bike is marvelously comfortable around town or on the highway. The seat is long and well padded, the suspension is compliant without being too soft, and the footpegs were in a comfortable position for nearly everyone. The polished passenger footpeg bracket also has a cast-in platform that can serve as both a toe rest for the passenger and a heel rest for the rider. This provides a floorboard effect that is very comfortable on long rides.

Although the wheelbase is 57 in., nearly the same as the Kawasaki’s and the Suzuki’s, the narrowness of the bike and the length of the seat make the bike feel longer and less cramped than either the Seca or the GPz. The rectangular tank adds to at least the illusion of length.

Larger riders generally felt they were on a larger, more comfortable bike.

Adding to riding enjoyment is the sound and feel of the engine. Even though the Vision is geared the lowest of any of the 550s, turning 5295 rpm at 60 mph, fewer firing pulses of the water cooled V-Twin give the bike a more laid back, relaxed feel on the highway. The water jacket damps out nearly all mechanical noise, so all you hear is a mellow Twin exhaust burble and a low-key whine from the straight cut primary gears. To go with the sound, the engine has wonderful roll-on power and good throttle response to go with it.

Usually. Our test bike developed a flat spot of! the line and an irregular idle, and we had to have the idle jets blown out. Toward the end of the test the same problem began to crop up again. The bike is new enough on the market that we don’t know if this is likely to be a recurring problem with the breed, or just an eccentricity of our test bike. In any case, it was one small running fault in an otherwise amazingly fast and tractable engine.

The Vision is the only bike in the test with shaft drive, a convenience for which it seems to pay almost no penalty. The bike’s weight is within a few pounds of all but the ultra-light Seca, and the rear end jacking effect that sometimes mars the handling of shaft drive bikes during on/ofif throttle applications is barely perceptible in the Vision. The shaft is most noticeable when other riders are oiling their chains and you aren’t.

There is no damping or preload adjustment on the front suspension and no air caps, but the single rear shock has six adjustment slots on its preload ring. Unlike the Kawasaki’s, this one is easily reached under the seat and can be moved quickly from one position to another with a shock tool.

The 4.5 gal. gas tank, third largest of the group, is still good sized and gives the bike well over 200 mi. of range. Instrumentation is relatively simple, the tach and speedo sharing the panel with only a water temp gauge and warning lights for oil, high beam and neutral. Handlebar controls are straightforward, with selfcancelling turn signals. Clutch pull is light, and shift action nearly as light as the Kawasaki’s, but with less lever travel.

Overall, a comfortable, supple, bike >

that makes nice sounds and good power, only a pair of handlebars away from being the most comfortable on the highway. If you like the bars, you’ll love the ride.

SUZUKI GS550M

Back to throttle response. We had to rate the Suzuki last in comfort and utility just because, as it came to us, the bike was nearly unrideable. Which is a shame, because the quick and simple carb fix turns the tables considerably.

With the carbs responding properly, the GS became one of the roadgoing and errand-running favorites of the group, for several reasons.

The bike has a huge 6 gal. gas tank that allows a good Sunday ride sans gas station search. To go with the long range is a riding position that manages to feel comfortable for both fast cornering and long highway rides. One rider complained that the seat felt a little too hard, but that was the only mention of any discomfort on an all-day ride. The front suspension is air adjustable and the rear offers both preload and damping adjustments on the easily reached dual rear shocks. Noticeable changes in ride can be made quickly and simply.

Like the 1000 Katana, the 550 is stiffly sprung and imparts a taut, rugged feel. This characteristic was admired by nearly everyone who rode the bike, and everyone described it in slightly different terms. Among them: “Feels like a motorcycle,” “The least Japanese feeling of the bunch. . .has a solid, hardware character,” and “Feels almost like it could have been made in Italy.”

Engine vibration reaches the rider more noticeably on the GS than with the other bikes, but, again, it imparts a hard, race bike sensation that no one objected to. The rear seat, which looks more like a tailpiece than a seat, is adequately comfortable, though passengers reported they were more inclined to hold on to the rider or seat strap, a little insecure due to the lack of backstop on the smooth, tapered seat.

Instrumentation is nicely laid out, with two separate round pods for the tach and speedometer and a panel between them with a digital gear position indicator, needle-style fuel gauge and the usual warning lights. Turn signals are not self-cancelling and there is a thumb operated choke lever at the left grip. Clutch pull is a bit heavier than that on the other bikes, but engagement is predictable and solid. The front brakes are simply the best of the group, powerful and easily modulated with very little effort at the lever.

The good brakes, big tank, light and accurate steering, good seating position and rugged simplicity made the bike a favorite on the highway and in town—once the carbs were fixed.

CONCLUSION

It wasn’t easy arriving at a conclusion in this comparison, largely because the bikes were so close in performance that, off the race track, the numbers were not critically important. Most of the faults were of the nit-picking variety and sweeping condemnations were hard to come by. None of the five test riders actively disliked any of the bikes or would object to owning any of them. They were all reasonably fast, fun, good handling and efficient. So what it boiled down to was our staff of dispassionate professionals picking different favorite bikes on such intangibles as aesthetics and that mysterious thing called “feel.”

Nevertheless, certain bikes rose to the top of the list more often than others for solid reasons of competence and allaround usefulness. Here’s the outcome, in order of preference based on Sound Reasoning. Dissent is noted, where appropriate.

KAWASAKI GPz550

As the quickest and fastest bike in a straight line, as well as being, demonstrably, the fastest way around a roadracing circuit, the GPz deserves to come out first in a comparison of 550 sport bikes. It’s fast, good handling, predictable and rugged. It has a big gas tank, a small fairing, and a comfortable seating position, despite the non-adjustability of the bars. The longer wheelba:^ and new suspension make it a more comfortable road bike as well as a terror on the track. It’s an allaround competent bike that does few things wrong and nearly everything right.

Objections? Occasional service problems with the valves, and a rear shock that’s hard to adjust. One rider asked, “What was the failure with twin shocks and how does a single shock improve on two? There are added pieces and joints and the single shock is now out of the air and closer to a heat source.” Another remarked that the bike started life as a really simple, straightforward motorcycle and was now becoming more cluttered with unnecessary trick items. Another said he thought painting all the GPzs the same color was a mistake; “Who wants to see himself coming down the road 10 times an hour?” The small fairing also drew criticism as an impediment to installing a fairing that works.

None of these complaints, however, takes away from the wonderful performance, good comfort and utility of the bike. It’s the racer’s favorite. Two of our testers listed it as their first choice and two as second choice, and one as his third. A strong finish for a strong bike.

SUZUKI GS550M

How did the slowest and worst running of the 550s end up in second place? Be-

cause for two of the riders the carb problem and lower power were the only things they didn’t like about the bike, and there are easy ways of fixing both. A third tester listed it as his second choice and the other two rated it third and fourth.

The Suzuki won points for having a big gas tank, tunable, easy to adjust suspension, tremendous -brakes, light, precise steering, mechanical tightness and superior road feel. Despite the wild and unconventional styling (which drew both the strongest likes and dislikes of the test), the GS comes across as a straightforward rugged motorcycle that has not given up anything in function or utility to achieve its appearance. “Honest” was a word often used.

On the basis of power and rideability, as delivered, this bike deserves to go straight to the back of the class. It’s a wonderful bike with an ill running engine. But the GS550 powerplant is a proven, reliable engine, and the two riders who picked this bike as first choice both said they would be willing to fiddle with the carbs, install an exhaust system with better ground clearance, and do any other performance work the bike needed to get up to speed, simply because they liked riding the bike.

If Suzuki ever gets its act together on the engine, the GS could be a dynamite motorcycle. As it is, it’s still a good bike, but you’ll have to go out and find your own dynamite.

YAMAHA SECA 550

The Seca came very close to beating the Suzuki out for second place. Everyone liked the bike, with the engine being singled out for special mention. The Seca motor is narrow, powerful and makes beautiful high-winding noises as it runs up through the gears. It manages to be both cammy and strong on the bottom end. Brakes and handling are good and the light weight of the Seca makes it your friend in town or moving it around the driveway. The smallest and lightest of the group, it is both agile and exhilerating to ride.

For all that, the bike may have ended up third merely for the capricious reason that it is a smaller bike. We have a couple of big galoots on the staff who felt just a bit cramped on the bike, or that one of the larger 550s would suit them better if a passenger were to be carried anywhere. The only other objection to the bike may also stem from the very lightness which is partly responsible for its fierce performance. Several riders said they thought the bike felt “less substantial” than the others or had a slightly stamped-out feel about it. Small quality items, such as the fairing having red overspray on its white inner surface bothered some.

In all, a very nice bike that finished very close to second in a race measured in inches and fractions of inches.

YAMAHA 550 VISION

Like the Seca, the Vision may have suffered just a bit from lack of definition. Both the Kawasaki and the Suzuki have harder edges to them, characteristics that bring praise or criticism, but unforgettable characteristics nevertheless. The Vision ended up last just because its personality is not as clearly defined as the others.

Yet as the sum of its features the Vision appears to be the most novel, different and distinctive bike of the group. It has a wonderful engine with gobs of midrange, plenty of peak power and a muted yet soulful Twin burble at any speed. On the race track it is the bike most likely to challenge the GPz, and on the highway it has room

and comfort for two. Distinctly modern looking, its lines have a clean pen-and-ink look to them, as though they just came off the drawing board.

The Vision is a lot of good ideas put together, but not quite as tightly as they should be. Everything about the machine is so soft, comfortable and competent that it makes no demands on the rider and leaves few impressions when he is done riding. This is the-first year for the Vision. With the same kind of refinement most of the other 550s have gone through it has great potential and may yet become the vivid motorcycle of the class. Pursuant to that end, it needs better or different handlebars, brakes with slightly better feedback and perhaps better springing and damping at the front end—or at least

some range of adjustment. As it is, the Vision remained perfectly well liked, but somehow unloved, among our test riders. It took four fourth places and one second in the voting on “which bike would you most like to have for your own?”

It is enjoyable to do a comparison test where the least favored bike can be such an excellent machine, and a tribute to the group that five testers can be so un-unanimous in their choices. At the end of the test, one of the riders looked at all four of the 550s lined up in the parking lot and said, “These bikes are so close in performance and capability, I think I’d tell people that, unless they’re going racing, they should just pick out the one that looks good to them. Faults are more fun to live with than a bike you don’t like.” Si