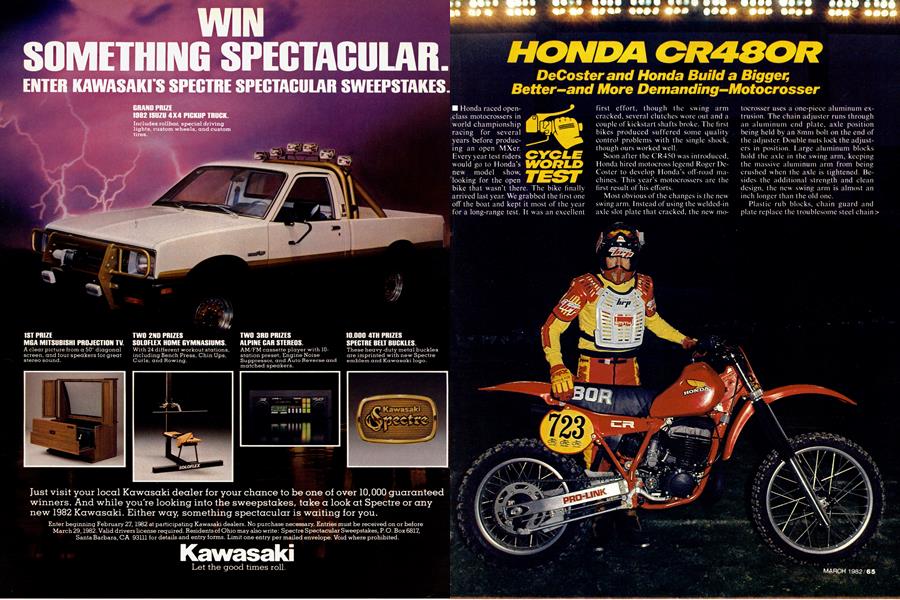

HONDA CR480R

CYCLE WORLD TEST

DeCoster and Honda Build a Bigger, Better—and More Demanding—Motocrosser

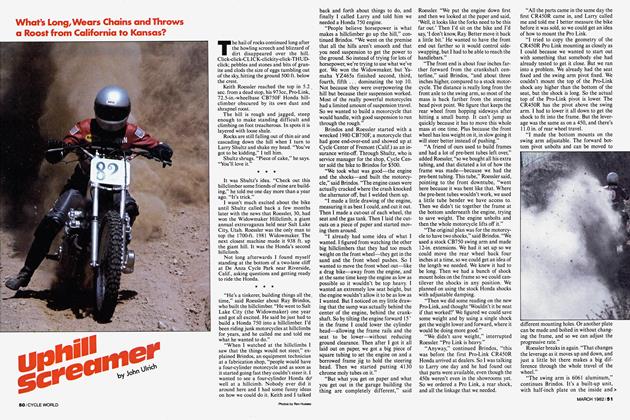

Honda raced openclass motocrossers in world championship racing tor several years Before producing an open MXer. Every year test riders would go to Honda’s new model show, looking for the open bike that wasn't there. The bike finally arrived last year. We grabbed the first one off the boat and kept it most of the year for a long-range test. It was an excellent first effort, though the swing arm cracked, several clutches wore out and a couple of kickstart shafts broke. The first bikes produced suffered some quality control problems with the single shock, though ours worked well.

Soon after the CR450 was introduced, Honda hired motocross legend Roger DeCoster to develop Honda’s off-road machines. This year’s motocrossers are the first result of his efforts.

Most obvious of the changes is the new swing arm. Instead of using the welded-in axle slot plate that cracked, the new motocrosser uses a one-piece aluminum extrusion. The chain adjuster runs through an aluminum end plate, axle position being held by an 8mm bolt on the end of the adjuster. Double nuts lock the adjusters in position. Large aluminum blocks hold the axle in the swing arm, keeping the massive aluminum arm from being crushed when the axle is tightened. Besides the additional strength and clean design, the new swing arm is almost an inch longer than the old one.

Plastic rub blocks, chain guard and plate replace the troublesome steel chain> guard. The quick-destruct chain rollers have been replaced by rollers with sealed needle bearings. An exposed cable with easy wing nut adjustment replaces the rear brake rod, the aluminum brake pedal with steel claw has been improved.

When the rear suspension on the 1981 CR450 worked, it was marvelous. Unfortunately, it often didn’t work. This year the large single shock is substantially improved. There are still four damping adjustments, but now they control compression damping instead of rebound damping, and the adjuster knob has easyto-read marks on the edge of the knob. A stationary valve replaces the floating valve, reducing internal heat build-up. Combined with a new reservoir and better shock oil the new shock should be less prone to fade.

A change in suspension linkage makes spring and damping rates softer in the middle of the rear wheel’s travel and makes the rate of progression softer as the shock is compressed.

Forks are entirely different, though the same 12 in. of travel is available. Stanchion tubes are 43mm this year, 2mm larger. Compression damping is adjustable by prying off a rubber cap and turning the adjuster to any of three positions with a small flat blade screwdriver. A stiffer spring means air pressure isn’t needed for most tracks, though air caps are still fitted.

A new front hub has a flared spoke flange on the brake side and integral flange on the small side instead of the bolted-on steel flanges used last year. Spokes now have a straighter pull, which should reduce the strain on spokes. New brake linings on the double leading shoe front brake are designed to resist fade better.

A thorough revision of the frame has changed many of the measurements, while the basic design is the same. The steering head has thicker wall tubing and is set at 27°. The swing arm pivot is moved half an inch farther forward in the chassis so the inch-longer swing arm stretches the wheelbase only half an inch. Good triangulation in the middle of the frame and healthy tube sizes are still provided.

Until the competition came out with monster engines up to 495cc, the 431cc Honda seemed to have an ample sized engine. So this year the bore has been increased 4mm, resulting in a displacement of 472cc. Stroke remains 76mm, with the crank, flywheels, transmission gears and ratios unchanged. Some metal around the countershaft sprocket has been removed so a one tooth larger sprocket can be added without it hitting the cases. Wider cork surfaces on the clutch plates provide 30 percent greater working area with the same number and size plates. Stronger springs are used, too.

The kick start lever has the security bolt running into a threaded hole in the center of the shaft, doing away with the groove that weakened the shaft last year. The relocated bolt also keeps the bolt head away from the clutch cover, which it used to hit if the lever was kicked all the way through.

By no accident, the changes mentioned here involve the weak points of the ’81, so components that worked well, for instance the 38mm Keihin carb and the sixpetal reed valve, aren’t changed.

The airbox now has splash guards riveted to each side and a removable splash pan on top, which looks like a good idea even though ours had bounced out of position every time we checked it. The molded rubber boot is thicker, so it can’t collapse, and we’re told the foam filter has different glue that won’t dissolve in gasoline.

The same detail treatment was given to the plastic parts. The front fender is thicker where it bolts to the lower triple clamp, the rear fender has some added bolts, ditto the side plate/number panels. The fuel tank has been enlarged from 2.4 to 2.5 gal. and the shape revised; the rear is thinner which lets the rider slide forward more easily. The seat has more padding and a stronger base. The number plate no longer has that odd upward tilt, cast steel pegs have sharper teeth and the handlebars have a different, lower bend.

With so many details changes the 1982 CR480 has many differences in dimension and specification. The new machines weigh 10 lb. less, thanks to use of aluminum instead of steel. To let the bike steer quickly despite the longer wheelbase and swing arm the steering head angle has gone from 29.5° to a steep 27°, footpegs and ground clearance are half an inch higher than before.

The 480 is a genuine brute to start. > That shouldn’t be all that surprising. This is a big engine. Also, the lever is on the left, which won’t surprise riders with experience on European bikes but which the younger set sometimes finds awkward. And to give more leverage the lever is longer but that means it’s also higher; no help when you’re already looking for a berm to stand on. Anyway, pussyfooting the lever won’t get you far. Several hearty kicks are needed, with the engine cold or hot. And don’t try it in the garage in your tennis shoes; one of our guys bruised his instep and he had his motocross boots on.

That part done, the engine doesn’t clatter or vibrate and it warms up quickly. Now get ready for the clutch. The clutch pull is heavier than last year’s—remember the stiffer springs—but not bad for an open class machine. The clutch disengages cleanly and the gearbox slips into first, but the clutch is in or out, instantly. Don’t bother trying to slip the clutch or release it progressively, you can’t. Most riders stalled the engine several times in the first 50 feet. Pull in the lever, drop into gear, feed some gas and release, quick as that.

The acceleration is just as quick. Our 480 came jetted right and running perfectly. No bog or blubber and each gear is an extension of the last. Fast. That’s the word we’re looking for.

Our 450R shifted fine but we heard of others whose bikes wouldn’t downshift to 1st under racing conditions, which usually meant leaping the berm in neutral. The factory says the transmission engagement dogs have been undercut and the female engagement slots have been lengthened on low gear. Because we didn’t have the problem, we can’t say it’s fixed, but the 480 shifted fine, up and down.

We had some reservations about the steep steering head angle. A 27° rake is more often seen on a trials or road racing bike, where quickness is everything, so we wondered how the 480R would act in sand and loose dirt. Our deepest sand wash surprised us. The 480 didn’t shake its head or wobble. Straight line stability is extremely good. Even slowing in sand fails to disturb the new Honda, thanks to the longer swing arm and frame geometry that enables it to work.

Where the 480 suffers is under hard braking on whooped ground. The steep rake combined with the long-travel suspension results in the front end developing almost negative caster. Full-lock tank slappers are possible unless the rider maintains a death grip on the bars. Even with full muscle the bike shakes its head on hard braking. It never pitched anyone off, but first-time riders all came back with eyes sunny-side up. The trick to riding the CR is to leave the throttle cracked when braking hard, minimizing the pitching of the machine.

Braking power was initially disappointing. It just didn’t have that run-into-awall feel of last year’s 450. After a couple of hundred miles the shoes seated and braking power increased to all we wanted. The exposed cable operating the rear brake has increased the feel of the rear brake, but it’s easier than ever to kill the engine by stabbing the rear pedal. This appears to be the result of too little flywheel. Entering bumpy, tight corners can be difficult because the light flywheel of the 480 doesn’t keep the engine running if too much rear brake is used. And the light flywheel makes restarting while bouncing through a corner more difficult. The only safe way through tough corners is with the clutch pulled in, which may not be a problem for pros, but is needlessly difficult for others.

Engine power is camouflaged by the light flywheels. It revs so quickly that it sounds pipey, even though it makes nice, smooth power over a wide range of engine speeds. For launching the 480 out of a bermed turn, the light flywheels are just the ticket. Just touch the clutch as you’re coming out of the turn and the bike explodes away, front wheel jumping into the air. Sheer horsepower eliminates any need to downshift.

Entering the 480 in competition brought out some surprising information. Its first race was at San Diego on the stadium course used the night before by the national riders. It was hard packed and tortuous. On this course the Honda was perfectly suited, its quick handling and instant power being just what the course demanded. With only 30 min. operation before the race, our pro rider left the suspension set as it came from Honda. It worked flawlessly and he won easily. It’s still nice to know that the other settings are available for other courses, though.

At the next race in Arizona the track had been flooded by two days of rain. Here the light flywheel made the bike harder to ride in the mud. Still, the rider was able to pull a 20 sec. lead by the time the checkered flag was in sight, only to have the chain jam full of mud and bring the bike to a dead stop three turns from the end. The chain guide had acted like a scoop in righthand corners, filling the sprockets and chain with crud.

The chain wasn’t the only problem. Longer motos were used in the Arizona race and the rear shock began to fade after 30 min. Another 5 min. and the damping was completely gone while the shock was red hot. Between motos the mud was scraped from the chain, the sprockets and from the engine that had heated up so much after being packed with mud that the base gasket had started leaking. With the cylinder nuts torqued and silicone seal wiped around the base gasket the 480 was ready for the second moto.

Even with plenty of time to cool off on the cold day the shock didn’t regain its damping. The bike bottomed and hopped its way around the course and managed to win the moto. Honda doesn’t recommend rebuilding the shock, but we wouldn’t throw one away. Many good companies rebuild or modify the shocks for less cost than a new shock.

Convinced that the Honda was competitive on the track, we installed a countershaft sprocket with an additional tooth, added a 3.5 gal. Clark gas tank and headed for Baja. Here the 480 had more shortcomings. Even one additional tooth didn’t raise the gearing enough for the fast roads of Baja. The quick steering and stiffer compression damping of the forks caused some exciting moments when rocks were hit off center. The suspension was well balanced with the fork damping at the softest position and the rear shock at position No. 2, so the rear end was left the same and that was slightly stiff.

Some of the characteristics that made this bike fast on the track made it unsuited for off-road use. The quick handling demands 100 percent concentration and this is tiring on long rides. The light flywheels let the engine rev too quickly, so the rear tire spends more time spinning than it should. The engine pinged badly on the Mexican gas, though it ran over 100 hard miles on the 3.5 gal. tank, much better than average. Fast, full-lock slides are easy with the instant power, but this becomes the only way the bike will handle some situations. It’s frequently necessary to run in a higher than normal gear and feather the throttle to keep the rear tire from spinning. It takes a lot of work to ride this bike fast off road.

HONDA

CR480R

$2248

Despite the improvements, the big CR isn’t any more of an off-road machine than before. It needs another transmission gear and heavier flywheels for that. As a motocrosser, it does much better. It’s smooth, doesn’t kick or buck and, until the shock fades, swallows up really bad terrain as well as any. It may be too quick in handling and power for other than professional riders, but there’s always next year.

And with Roger De Coster on Honda’s side, nobody’s going to bet against that.