KAWASAKI KX500

CYCLE WORLD TEST

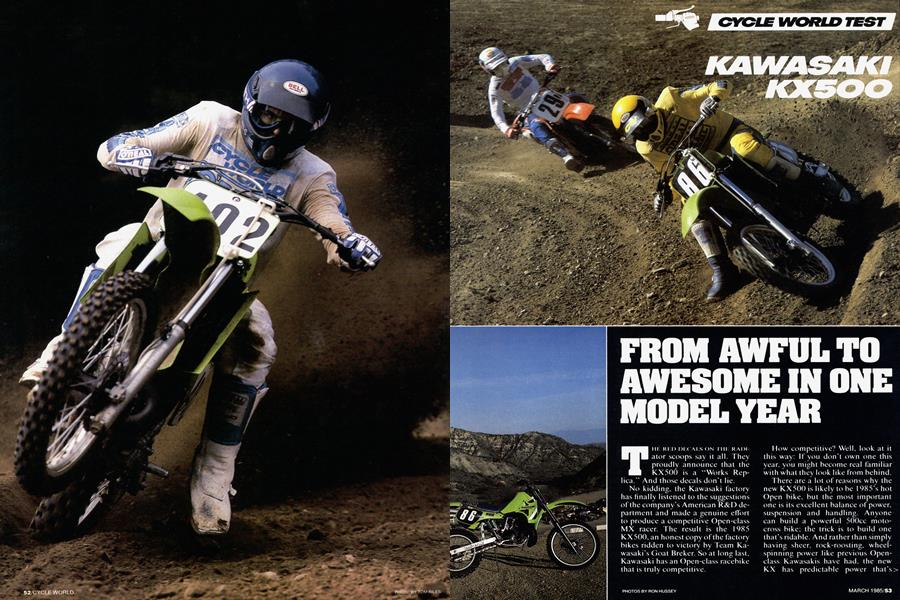

FROM AWFUL TO AWESOME IN ONE MODEL YEAR

THE RED DECALS ON THE RADIator scoops say it all. They proudly announce that the KX500 is a “Works Replica.” And those decals don't lie.

No kidding, the Kawasaki factory has finally listened to the suggestions of the company's American R&D department and made a genuine effort to produce a competitive Open-class MX racer. The result is the 1985 KX500, an honest copy of the factory bikes ridden to victory by Team Kawasaki's Goat Breker. So at long last, Kawasaki has an Open-class racebike that is truly competitive.

How competitive? Well, look at it this way: If you don't own one this year, you might become real familiar with what they look like from behind.

There are a lot of reasons why the new KX500 is likely to be 1 985's hot Open bike, but the most important one is its excellent balance of power, suspension and handling. Anyone can build a powerful 500cc motocross bike; the trick is to build one that’s ridable. And rather than simply having sheer, rock-roosting, wheelspinning power like previous Openclass Kawasakis have had, the new KX has predictable power that's available—and most important, usable—anytime, anywhere, in any gear, at any rpm.

A couple of hearty kicks on the aluminum kickstart lever brings the engine to life. And it doesn’t take long for anyone who’s ever spent much time on an Open-class motocrosser to sense that something is wrong, or at least different; because while Openclassers traditionally vibrate fairly heavily at low revs, this one is as smooth as most 250s. You won’t think it’s a 250 for long, though. Pulling away from the starting gate proves thrilling, for the engine revs quickly and powerfully, and the front wheel is in the air most of the time.

Braking for the first turn, the rider is aware of strong, predictable, wellmatched brakes. And when pitching the KX500 into that or any other turn, the bike feels light, agile and neutral, almost like a 250. Unless a turn is exceptionally tight, there’s no need to downshift below third, because the square-dimensioned (86mm bore, 86mm stroke) engine is responsive, clean-running and amazingly powerful even down at idle speeds. But it’s also impressive at higher rpm, able to propel the KX down the straights at warp speed. Fourth gear delivers all the speed most people will ever need on a motocross track unless there’s a long, long straight that will allow the bike to approach its 88-mph top speed.

With all that power available, getting the KX out of the starting gate quickly takes a little practice. The engine makes so much low-end power that slipping the clutch all the way to the first turn is usually necessary, otherwise the KX will fly the front wheel and the rider will have to back off the throttle. A comparatively short, 58.5inch wheelbase, (Honda’s CR500R is an inch longer) also contributes to the light-feeling front end.

If gated properly, there’s little fear of the KX being outrun to the first turn, for few Open bikes produce as much power; and only the CR500R comes close to producing such controllable power. Still, the secret to getting the best from the KX is shortshifting so the rear tire doesn’t spin excessively. And after lapping the track for 15 minutes or so, a fast Intermediate or Pro rider may notice some pinging at low engine revs. The ping isn’t extreme, but it’s not desirable, either. Changing the sparkplug from an NGK B8ES to a colder B9ES cured the problem on our bike.

Although the KX500 engine behaves like an all-new powerplant, it actually is based on the ’84 bike’s lower end and transmission. There’s a new kickstart gear (made separate from the redesigned clutch hub) that eliminates chatter when the clutch is released at high engine revs, plus a recalibrated ignition, a new liquidcooled cylinder with revised porting, a higher-compression head with small cooling fins on top, and a new pipe to fit around the right-side radiator. The low-speed power is aided by a 40mm carb that uses Mikuni’s flatbottom, R-type throttle slide. A boost bottle, which is mounted on the right side of the frame and connected to the reed-valve intake manifold by a large rubber hose, helps sharpen low-speed engine response.

.»there’s little fear of the KX being outrun to the first turn, for few Open bikes produce as much power.”

Having a great engine is swell, but the equation isn’t complete unless the chassis and suspension work equally well. And on the new KX500, they do. An all-new frame, shared with the KX250, features a 28-degree head angle, large-diameter tubing for strength, and a silver paint job for looks. A box-section aluminum swingarm provides strength while adding flash.

Aluminum is also used for the adjustable Uni-Trak strut that has a grease fitting at each end to ease maintenance. The Uni-Trak rocker is fabricated from welded steel plate, and it pivots in bearings, although disassembly is still required when it’s time to lubricate. The wheel-to-shock leverage ratios are the same as in ’84, but the KX has a new KYB shock with adjustable everything. A plastic knob at the top of the shock adjusts the rebound damping to any of 20 positions, although you must first remove the seat. The compressiondamping adjusters might cause a few people to take a second look, because there are two knobs on the end of the shock's remote reservoir. The larger knob adjusts the high-speed compression damping (4 positions), and the smaller knob alters the low-speed compression damping ( 14 positions). In addition, the spring preload is adjustable by turning the rings under the shock spring.

Regardless of the number of adjustments, however, tuning the shock to suit various rider levels and track conditions proved simple. For a Prolevel racer. No. two on the highspeed compression adjuster did the job; the low-speed compression adjuster gave him the best results eight clicks out from a fully-seated clockwise position. Ten clicks out on the rebound damping adjuster knob, the standard position, worked fine.

With an Intermediate racer aboard, we softened the high-speed compression by turning the knob to the No. one position but didn't alter the other adjustments. The shock spring was adjusted for rider weight by turning the preload ring to obtain a measured 4 inches of sack.

Adjusting the KYB fork was equally simple; we preferred the compression-damping blow-off adjuster (on the bottom of each slider) set in the middle of its eight-click range regardless of rider classification. Oil level and weight were left stock. The fork’s spring rates are right for most Intermediate to Pro-level racers who weigh between 150 and 180 pounds. If they so wish, heavier riders can up the preload on the fork springs by turning a nut on the top of each stanchion tube; an internal ramp device adds 5mm of preload with each quarter-turn of the nut, which can rotate a half-turn for a total of 10mm additional preload. And if lighter riders find the stock springs too stiff, Kawasaki offers an optional lighter-rate spring. Our test-riding crew (made up of Pros and Intermediates) preferred the spring preload in the standard position, but one Intermediate felt the fork springs were a little stiff for his weight and speed.

Although adjustable suspension has become standard equipment on modern MX bikes, the adjustments on the KX are exceptional because they actually make a big difference; on some bikes, the adjustment knobs require several turns—and often a lot of imagination—before you can feel any change. So the KX’s suspension is a big bonus for a rider who races on several different tracks.

And once the KX500’s suspension is fine-tuned, there is no need to worry about another brand handling better. It’s hard to fault the KX500 in the suspension department; bumps, holes, whoops, drop-offs and all other normal pitfalls of motocross racing are taken in stride. The rear tire follows the bumps when the bike is accelerating out of turns, and when braking hard into them. The KX lands smoothly from the highest jumps, with no harsh thud or excessive rebound. And the bike flies straight and true when launched into the air. Long motos will get the shock reservoir hot to the touch, and Pro riders may even notice a slight loss of shock damping, but the condition never is severe enough to cause more than occasional bottoming.

In the past, Kawasaki’s motocross bikes have taken a lot of flak from riders who thought the handlebars were positioned too close to the rider. That complaint is no longer valid, thanks to new offset, rubbermounted handlebar perches. Our bike was delivered with the offset facing toward the front, a position all of our testers preferred. Kawasaki also has eliminated another complaint many voice when climbing aboard an Open-class motocrosser: the big feel. The KX’s comparatively low seat (36.3 inches) lets most racers touch the ground fairly easily, and the narrow, low-mounted gas tank helps create the illusion of smallness. Moving around on the KX is easy, too; the flat-top seat blends nicely into the gas tank, and doesn’t require you to climb up on the tank when you need to get forward for cornering. And when moving your weight to the rear for jumps and whoops, the narrow midsection doesn’t drag on your legs or interfere with movement.

An Open-class MX bike often is preferred by retired motocross racers for trail riding and grand prix racing, and the KX500 will be a good choice for them (except, perhaps, for its small gas tank). The wide-ratio, fivespeed transmission offers a gear for every situation, and the KX’s seemingly limitless power is wonderful for all sorts of off-roading. And the surprisingly low level of vibration makes day-long riding a pleasant affair.

Being pleasant is always nice, and being pleasant ¿^¿/competitive is even nicer. The K.X500 is both. We raced our bike in the Pro and Intermediate classes and won, even though the riders were unfamiliar with the machine. We also drag-raced the KX500 against the Honda CR500R we tested in December; the KX won every drag by at least a bikelength through fourth gear, then jumped from four to eight bikelengths ahead after shifting into fifth. The KX’s wide-ratio transmission is responsible for much of the big difference in the two bikes in fifth gear, but we also suspect that the KX is making more power. It’s a real performer, and not just in terms of engine power.

To tell you the truth, no one is more suprised in the performance of the KX500 than we are. We rode a pre-production KX500 prototype several months ago and, as we reported, it was quite good—so good, in fact, that we suspected that maybe Kawasaki had slipped us a ringer. After all, when a company has such a good 500cc prototype after traditionally building some of the worst 500cc production bikes available, there is reason for doubt.

That doubt was unnecessary. Our test KX500 is a production unit, and if anything, it's even better than the prototype we rode. Matter of fact, we think the KX500 is the best Openclass motocrosser available from Japan. We haven’t yet tested the new crop of European 500s; but if they intend to outdo the KX500, they've got their hands full.

KAWASAKI

KX500

List price $2699

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

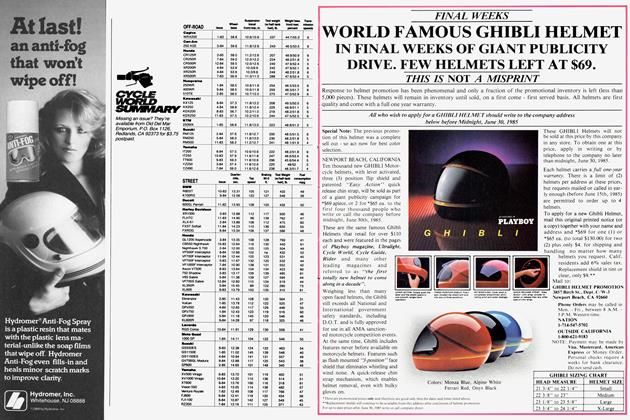

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

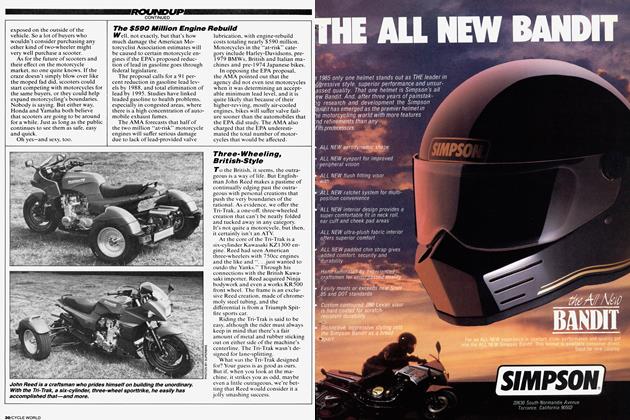

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985