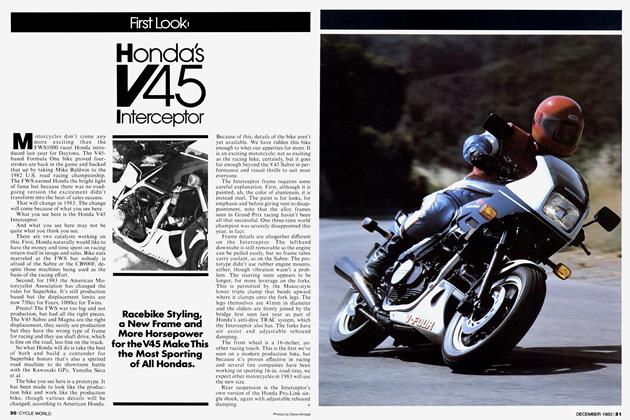

KAWASAKI KZ1100 SHAFT

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Smoother. Faster and Lighter Than Its Predecessor, the KZ1100 Shaft is a Big Brute of a Touring Bike

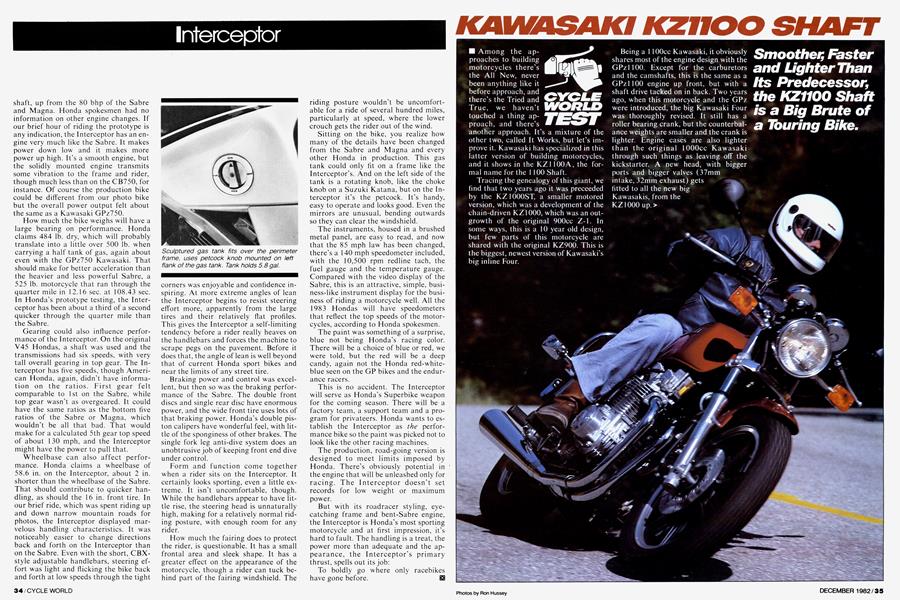

■ Among the approaches to building motorcycles there’s the All New, never been anything like it before approach, and there’s the Tried and True, we haven’t touched a thing approach, and there’sR another approach. It’s a mixture of the other two, called It Works, but let’s improve it. Kawasaki has specialized in this latter version of building motorcycles, and it shows in the KZ1100A, the formal name for the 1100 Shaft.

Tracing the genealogy of this giant, we find that two years ago it was preceeded by the KZ1000ST, a smaller motored version, which was a development of the chain-driven KZ 1000, which was an outgrowth of the original 900cc Z-l. In some ways, this is a 10 year old design, but few parts of this motorcycle are shared with the original KZ900. This is the biggest, newest version of Kawasaki’s big inline Four.

Being a 1 lOOcc Kawasaki, it obviously shares most of the engine design with the GPzllOO. Except for the carburetors and the camshafts, this is the same as a GPzllOO engine up front, but with a shaft drive tacked on in back. Two years ago, when this motorcycle and the GPz were introduced, the big Kawasaki Four was thoroughly revised. It still has aR

All the big Kawasakis get some kind of rubber engine mounting, too, but it’s not all the same. Holding alignment between the engine’s sprocket and the rear wheel sprocket is important on the chain drive GPz, so that bike only has two of its mounting points held in rubber. On the KZ1100 only the swing arm pivot is solid, with the rest of the mounts held in rubber isolating bushings.

No 1 lOOcc Kawasaki Four will ever be slow, but there are differences in how the various models are fast. For the GPz version, absolute maximum power is what Kawasaki wants, so that bike gets cams with 280° of duration. That makes for more peak power, at high rpm. For the shaft drive KZ1100, more power at lower rpm is needed, so its cams have 270° of duration. Lift is the same for both, and all the big Kawasakis get the same 8500 rpm redline on the electronic tachometer.

To take advantage of this slight difference in powerband, the gearing is just as slightly different. Transmission ratios are the same in all the big Kawasakis, but the shaft drive model has a taller final drive, 2.45:1 instead of the 2.73:1 of the original GPz. Gearing on the shaftdrive bike is not so easily changed, but the ratios chosen are satisfactory. The original KZ1000 Shaft had lower gearing. That was one of the major problems with the bike. The low gearing made for lots of vibration with the solidly mounted motor, plus there was too much noise, and too little economy. The new gearing is not a drastic change. Engine speed at normal highway rates is maybe 300 rpm less. In combination with the rubber mounted engine, vibration is pleasantly low and the noise isn’t bad, even on a full dress version. Economy is still nothing to brag about, with the stripped KZ1100 Shaft averaging 43 mpg on our 100 mi. loop. Either a higher overall gear ratio, or a wider ratio transmission combined with a taller top gear ratio would make for a more comfortable motorcycle, though some slight acceleration would be sacrificed.

Chances are the owner of a KZI 100, any model, won’t be complaining about the lack of power and acceleration. If the Shaft model isn’t quick enough, there’s the GPz, and if it’s not thrilling enough, you’d better start looking at wheelie bars, 18-in. wide slicks and giant superchargers. This is an enormously strong, fast motorcycle in the fashion that only great, big motors can provide. Dragstrip figures don’t do this kind of performance justice because the test rider, who doesn’t have a dime in the bike, can squeeze performance out of smaller motorcycles that owners seldom use. Fast starts on a 550 require holding the engine at redline and carefully slipping the clutch, followed by speed shifts. On a bike like the 1 100, there’s no need to rev the engine over 4000 rpm. It’s easy to make fast starts. Just let the clutch out, give it a little gas and hold on. Passing the auto-bound is just as easy. Twist the throttle and the 1100 hurries past, downshifts optional for the rider who wants more lunge.

This kind of performance surplus is especially valuable to the rider who puts on a fairing, saddlebags, top box, wife and 200 lb. of kitty litter. It still whistles down the road, over the mountain and away from stoplights effortlessly. It doesn’t remain a low 12 sec. quarter mile bike when fully loaded, but it loses less performance than a smaller motorcycle.

Think of it as big bike performance. It doesn’t come from turbos or 10,000 rpm redlines or fists full of valves. It comes from displacement. Onto that displacement Kawasaki has built a relatively efficient engine and placed it into a pleasant motorcycle. But performance isn’t free. The Kawasaki KZI 100 Shaft pays for its performance with weight. It also uses more gas than some smaller motorcycles.

Moving all this weight takes effort, whether the rider is trying to put the bike on the centerstand, or threading the motorcycle through curves on a road. The centerstand, more than anything else, accentuates the weight of the motorcycle, because it lifts the bike more than average and the lever doesn’t help much lifting the bike. It’s as hard to put on the centerstand as any motorcycle made.

Once on the centerstand, there are a couple of security devices available. The centerstand can be locked down with the key, and there’s an optional security cable that slides into the frame through a lug on the lefthand side of the bike. Both are convenient to use, though the cable is a little stiff to remove and replace. The other security devices on the bike include a fork lock set through the ignition switch and an anti-hotwire shield on the electrics.

With all the anti-theft devices turned off, unconnected and retracted, it’s still heavy. A half tank of fuel brings the weight to 574 lb. Kawasaki says this machine weighs about 20 lb. less than the original KZ1000 Shaft. According to the scales, it’s on a par with the big shaft drive Suzuki and lighter than a Gold Wing. But the weight is carried high on the Kawasaki, and the suspension doesn’t sack much, so steering the Kawasaki takes muscle and concentration. It can go through corners quickly, for a touring bike, but the rider has to push it through. Cornering clearance is very good, though the tires felt squirrelly at times. On a full dress version of the 1100 there was more low-speed steering oscillation than normal, but it was easily controlled with hands on the bars.

Straight lines are more natural for the big Kawasaki. It’s stable and the suspension is suited to carrying lots of weight. Once again Kawasaki listened to comments about the 1000 Shaft, a bike that was woefully undersprung, and equipped the 1100 with a beefier suspension. The long-travel forks have medium-stiff coil springs assisted by air pressure. There’s only one filler, on top of the left fork leg, with a crossover tube connecting the two legs. In back there are air-assist shocks, again interconnected, with the air valve mounted under the hinged seat. Shock damping is adjustable by spinning the small plastic discs at the top of the shocks to any of the four positions.

Spring and damping rates on the 1100 are much stiffer than the suspension pieces on the 1000. For a stripped bike, even with the air pressure at minimum recommended settings, the bike feels firm, with little of the suspension travel used during normal riding. Even with air pressure at atmospheric pressure, the bike is never soft. It’s easy to pump the suspension up to average pressures and find the Kawasaki bouncing over ripples in the highway, the back end topped out and the front moving only slightly. The recommended air pressure range for the forks is 7.1 to 10 psi. In back the range is from 5.7 to 21. Unlike most motorcycles with air assist suspension, the Kawasaki responds noticeably to changes in air pressure.

This pays off when the owner stacks on full touring accessories, adding 100 lb. to the bare bike, and then fills those accessories, adding another couple of hundred pounds. Then the suspension can receive a little air and the bike still doesn't bottom or wallow. There is probably room for improvement in suspension compliance, even with the relatively stiff suspension rates now used.

What makes the suspension seem firmer than it is, is the seat. According to Kawasaki it uses dual densities of foam, which sounds good. And it’s a good looking seat, not too contoured, so a rider should be able to move around some and find a more comfortable spot. The only problem is that it doesn’t work. An hour on the Kawasaki seat makes anyone squirm. More time than that falls under the definition of cruel and unusual punishment. The seat is sloped so a passenger gets pushed forward, and the rider is also forced into one position on the seat somehow. The foam, both densities, is firm. It is a nice looking seat that doesn’t work.

If it weren’t for the seat, comfort wouldn’t be bad. The handlebars are about average in pullback and bend, and better yet, they are those marvelous round tube bars that can be so easily changed. Position of all the controls was reasonable, especially for a motorcycle that is likely to find itself carrying a fairing or some kind of windshield. Okay, clutch lever effort could be reduced, and so could throttle effort. On a long ride the right arm doesn't need that much work. Shifting is a delight. Not one missed shift, and the gears are well spaced. Only finding neutral could be easier, and to do that Kawasaki has a neutral finder. When the motorcycle isn't moving, it can’t be shifted past neutral. Come to a stop, push down on the lever until nothing happens, then lift up and you're in neutral. It’s easy, but it makes finding neutral on the roll more difficult, and it has another problem, too. It makes the motorcycle impossible to start if the battery is low. There is no kickstart lever. That went away several years ago. And pushstarting a bike that can’t be shifted into 2nd or 3rd gear is impossible. Leave off the neutral finder, and we'll be happier, Kawasaki. And as long as useless features are being removed, take off the clutch interlock, too.

Among useless gadgets, include the gas gauge. Even riders on the staff who like gas gauges (yes, there is one) found the Kawasaki gauge to be useless because it was so inaccurate. Until the first gallon of gas is used, the needle stays at full. And before the tank is two-thirds empty, the needle is resting on empty, past the red marking that might indicate reserve. When the bike starts sputtering and hinting that reserve would be nice, there is still about 2 gal. of gas in the medium-large 5.6 gal. tank. The trip odometer makes a much more useful indicator of tank level. Of course the normal odometer can’t be read from a normal seating position because of the angle at which it is mounted.

Other complaints? Yes, there are a few. Primary drive noise on big Kawasakis has always been noticeable. It’s still too loud, though the stripped bike made more sound than the dresser, this time. Brakes are a mixed bag. Since Kawasaki reduced the size of discs a couple of years ago, it has had the poorest feeling brakes available on big, Japanese motorcycles. But stopping distances on the 1100 are excellent, 119 ft. from 60 and 37 ft. from 30. Lever effort is high, the system is mushy, and control at maximum braking is difficult. This is a more noticeable problem on an 1 lOOcc, full dress touring bike than on the standard 1100 Shaft. Certainly there is enough braking power available, but it could be easier to use by making a braking system with a more solid lever feel and less effort necessary.

Despite a few nuisances, this is a good motorcycle. The basics are all here. Engine power is excellent, and control ideal. The suspension works well enough for most touring use. Certainly it is a big, solid motorcycle, a platform that can be equipped however an owner wishes, with the accessories offered by Kawasaki or those from other suppliers. It’s easy to mount accessories.

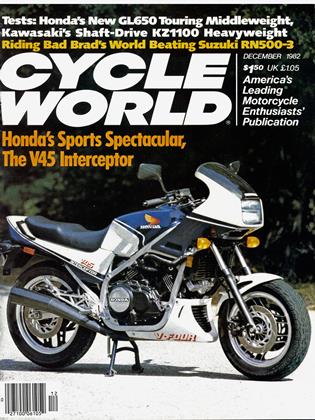

One of the Kawasaki’s best features may not be noticed by most people. That’s its clean, understated styling. Surround by flash bikes like the GPz, eye catchers like the Spectres, and luxurious tourers like the Honda Aspencade, the Kawasaki looks almost plain. But the details on the bike, the aluminum triple clamps, and the attractive pieces like exhaust collars, give the big Kawasaki an honest look that’s all too rare. Its fenders are painted and big enough to work. Extra plastic pieces are kept to a minimum. The polished aluminum engine and bright pieces are much easier to keep clean than black-painted engines. Even the paint, metallic red, is as average a color as you can find for a motorcycle. But it’s well applied and looks good.

Two years ago the Kawasaki KZ1000 Shaft was stacked up against all the other touring bikes in a touring bike comparison test in Cycle World. Competition was tough. The Kawasaki didn’t fare well, and we concluded by saying: “Get rid of the vibration, quiet it down, gear it up, put on a bigger gas tank and stiffen the rear springs and the KZ would be great.”

Well, Kawasaki has done everything we asked for. All that’s left are details. HÜ

KAWASAKI

KZ1100 SHAFT

$4099

View Full Issue

View Full Issue