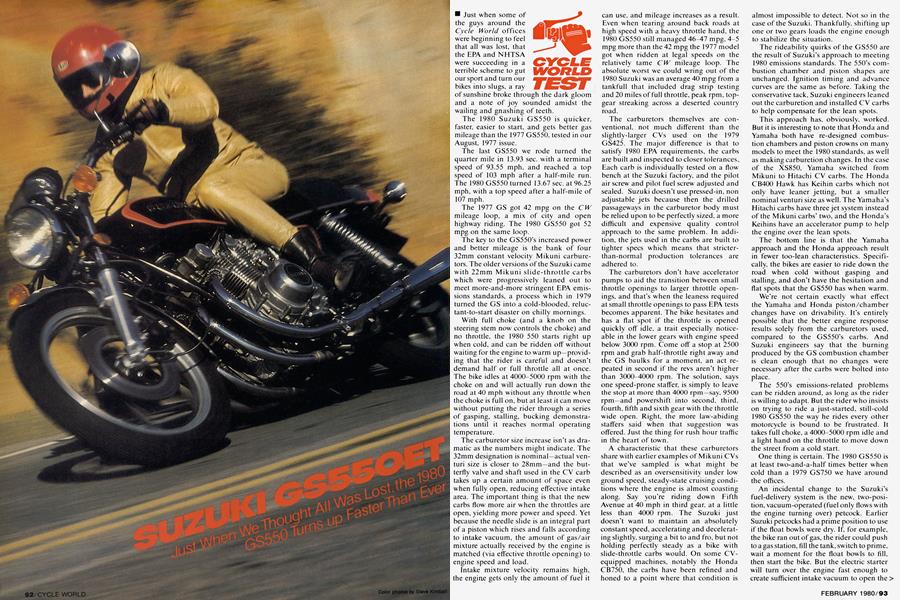

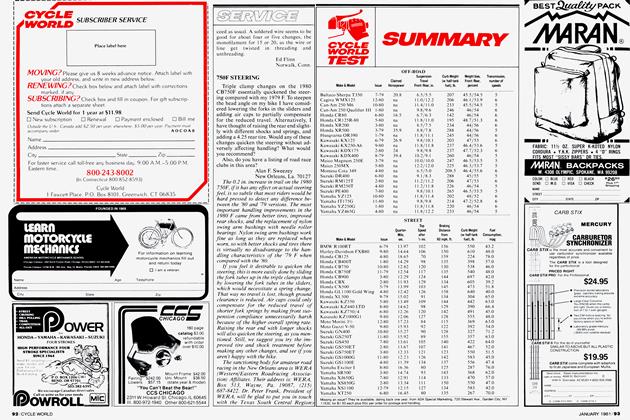

SUZUKI GS550ET

Just When We Thought All Was Lost, the 1980 GS550 Turns up Faster Than Ever

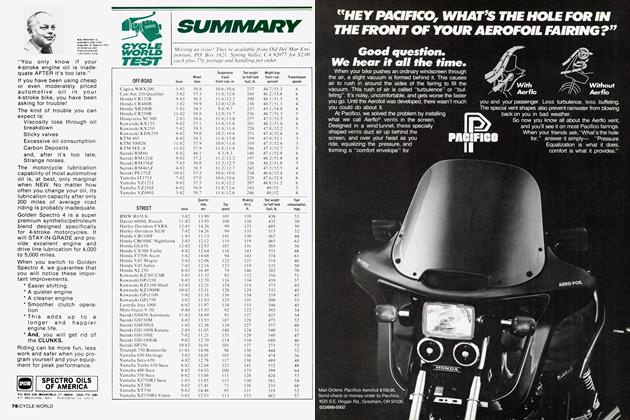

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Just when some of the guys around the Cycle World offices were beginning to feel that all was lost, that the EPA and NHTSA were succeeding in a terrible scheme to gut our sport and turn our bikes into slugs, a ray of sunshine broke through the dark gloom and a note of joy sounded amidst the wailing and gnashing of teeth.

The 1980 Suzuki GS550 is quicker, faster, easier to start, and gets better gas mileage than the 1977 GS550, tested in our August, 1977 issue.

The last GS550 we rode turned the quarter mile in 13.93 sec. with a terminal speed of 93.55 mph, and reached a top speed of 103 mph after a half-mile run. The 1980 GS550 turned 13.67 sec. at 96.25 mph, with a top speed after a half-mile of 107 mph.

The 1977 GS got 42 mpg on the CW mileage loop, a mix of city and open highway riding. The 1980 GS550 got 52 mpg on the same loop.

The key to the GS550’s increased power and better mileage is the bank of four 32mm constant velocity Mikuni carburetors. The older versions of the Suzuki came with 22mm Mikuni slide-throttle carbs which were progressively leaned out to meet more-and-more stringent EPA emissions standards, a process which in 1979 turned the GS into a cold-blooded, reluctant-to-start disaster on chilly mornings.

With full choke (and a knob on the steering stem now controls the choke) and no throttle, the 1980 550 starts right up when cold, and can be ridden off without waiting for the engine to warm up—providing that the rider is careful and doesn't demand half or full throttle all at once. The bike idles at 4000-5000 rpm with the choke on and will actually run down the road at 40 mph without any throttle when the choke is full on, but at least it can move without putting the rider through a series of gasping, stalling, bucking demonstrations until it reaches normal operating temperature.

The carburetor size increase isn’t as dramatic as the numbers might indicate. The 32mm designation is nominal—actual venturi size is closer to 28mm—and the butterfly valve and shaft used in the CV carb takes up a certain amount of space even when fully open, reducing effective intake area. The important thing is that the new carbs flow more air when the throttles are open, yielding more power and speed. Yet because the needle slide is an integral part of a piston which rises and falls according to intake vacuum, the amount of gas/air mixture actually received by the engine is matched (via effective throttle opening) to engine speed and load.

Intake mixture velocity remains high, the engine gets only the amount of fuel it can use, and mileage increases as a result. Even when tearing around back roads at high speed with a heavy throttle hand, the 1980 GS550 still managed 46-47 mpg, 4-5 mpg more than the 42 mpg the 1977 model got when ridden at legal speeds on the relatively tame CW mileage loop. The absolute worst we could wring out of the 1980 Suzuki was an average 40 mpg from a tankfull that included drag strip testing and 20 miles of full throttle, peak rpm, topgear streaking across a deserted country road.

The carburetors themselves are conventional, not much different than the slightly-larger CVs used on the 1979 GS425. The major difference is that to satisfy 1980 EPA requirements, the carbs are built and inspected to closer tolerances. Each carb is individually tested on a flow bench at the Suzuki factory, and the pilot air screw and pilot fuel screw adjusted and sealed. Suzuki doesn’t use pressed-in, non adjustable jets because then the drilled passageways in the carburetor body must be relied upon to be perfectly sized, a more difficult and expensive quality control approach to the same problem. In addition, the jets used in the carbs are built to tighter specs which means that stricterthan-normal production tolerances are adhered to.

The carburetors don’t have accelerator pumps to aid the transition between small throttle openings to larger throttle openings, and that’s when the leaness required at small throttle openings to pass EPA tests becomes apparent. The bike hesitates and has a flat spot if the throttle is opened quickly off idle, a trait especially noticeable in the lower gears with engine speed below 3000 rpm. Come off a stop at 2500 rpm and grab half-throttle right away and the GS baulks for a moment, an act repeated in second if the revs aren’t higher than 3000-4000 rpm. The solution, says one speed-prone staffer, is simply to leave the stop at more than 4000 rpm—say, 9500 rpm—and powershift into second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth gear with the throttle wide open. Right, the more law-abiding staffers said when that suggestion was offered. Just the thing for rush hour traffic in the heart of town.

A characteristic that these carburetors share with earlier examples of Mikuni CVs that we’ve sampled is what might be described as an oversensitivity under low ground speed, steady-state cruising conditions where the engine is almost coasting along. Say you’re riding down Fifth Avenue at 40 mph in third gear, at a little less than 4000 rpm. The Suzuki just doesn’t want to maintain an absolutely constant speed, accelerating and decelerating slightly, surging a bit to and fro, but not holding perfectly steady as a bike with slide-throttle carbs would. On some CVequipped machines, notably the Honda CB750, the carbs have been refined and honed to a point where that condition is almost impossible to detect. Not so in the case of the Suzuki. Thankfully, shifting up one or two gears loads the engine enough to stabilize the situation.

The rideability quirks of the GS550 are the result of Suzuki’s approach to meeting 1980 emissions standards. The 550’s combustion chamber and piston shapes are unchanged. Ignition timing and advance curves are the same as before. Taking the conservative tack, Suzuki engineers leaned out the carburetion and installed CV carbs to help compensate for the lean spots.

This approach has, obviously, worked. But it is interesting to note that Honda and Yamaha both have re-designed combustion chambers and piston crowns on many models to meet the 1980 standards, as well as making carburetion changes. In the case of the XS850, Yamaha switched from Mikuni to Hitachi CV carbs. The Honda CB400 Hawk has Keihin carbs which not only have leaner jetting, but a smaller nominal venturi size as well. The Yamaha’s Hitachi carbs have three jet system instead of the Mikuni carbs’ two, and the Honda’s Keihins have an accelerator pump to help the engine over the lean spots.

The bottom line is that the Yamaha approach and the Honda approach result in fewer too-lean characteristics. Specifically, the bikes are easier to ride down the road when cold without gasping and stalling, and don’t have the hesitation and flat spots that the GS550 has when warm.

We’re not certain exactly what effect the Yamaha and Honda piston/chamber changes have on drivability. It’s entirely possible that the better engine response results solely from the carburetors used, compared to the GS550’s carbs. And Suzuki engineers say that the burning produced by the GS combustion chamber is clean enough that no changes were necessary after the carbs were bolted into place.

The 550’s emissions-related problems can be ridden around, as long as the rider is willing to adapt. But the rider who insists on trying to ride a just-started, still-cold 1980 GS550 the way he rides every other motorcycle is bound to be frustrated. It takes full choke, a 4000-5000 rpm idle and a light hand on the throttle to move down the street from a cold start.

One thing is certain. The 1980 GS550 is at least two-and-a-half times better when cold than a 1979 GS750 we have around the offices.

An incidental change to the Suzuki’s fuel-delivery system is the new, two-position, vacuum-operated (fuel only flows with the engine turning over) petcock. Earlier Suzuki petcocks had a prime position to use if the float bowls were dry. If, for example, the bike ran out of gas, the rider could push to a gas station, fill the tank, switch to prime, wait a moment for the float bowls to fill, then start the bike. But the electric starter will turn over the engine fast enough to create sufficient intake vacuum to open the > petcock diaphragm, something kickstarting couldn’t do. This year the GS series machines don’t have a kickstarter (to save weight) so Suzuki engineers simplified the petcock as well.

The absence of the kick starter and associated shafts and gears may explain why the GS550ET, which has cast wheels and disc brakes front and rear, weighs just one pound more than the spoke-wheeled, rear-drum-brake standard GS550 we tested in 1977, 467 lb. compared to 466 lb.

Also new for 1980 is the addition of Suzuki’s transistorized ignition system. It has the same advance curve (indeed, the same mechanical advance mechanism) as the breaker points system it replaces, and maintains constant timing and spark intensity regardless of miles traveled. The latest EPA standards require that a manufacturer certify that emissions won’t rise above the maximum allowed even after 50,000 miles, and meeting that rule is easier with an electronic system. (Since rubbing blocks wear and points pit and collect deposits—thereby changing timing and spark intensity—a bike with a breaker points ignition would have to be set up farther on the safe, lean side of EPA requirements when new in order to still be legal after normal deterioration of the points system.)

It’s possible to retro-fit the new ignition system to an older GS550, since the crankshaft taper is the same and the backing plate mounting is identical. But since the complete Suzuki system costs over $200 and since accessory electronic ignitions are available for around $100, it’s doubtful that anybody would want to install the 1980 GS system on their earlier Suzuki.

Besides the EPA certification benefits, it’s possible that the electronic system contributes to the 1980 GS550’s horsepower gain by eliminating points bounce (and thus ignition timing variance) at high rpm. The GS makes its best power between 7000 and 9000 and pulls strongly above 6000, but still makes enough power for top-gear passing or climbing hills on the interstate from 5000 rpm (about 60 mph). Sixth gear on the Suzuki isn’t what you’d call an overdrive, however. At cruising speeds of 65-70 mph, changing from fifth to sixth or sixth to fifth gear will affect engine speed less than 500 rpm, and that fact has a lot to do with the engine’s top gear responsiveness.

The carburetion and ignition systems are not the only things changed on the GS for 1980. The frame now has tapered roller steering head bearings, which should end problems commonly encountered with the previously-used ball bearings dimpling the steering head races. But our test bike was delivered with the steering head undertightened and the forks clicked and moved around under hard braking. It took several cuts with the wrench to get the bearings to their proper load and eliminate the front end slop.

The control levers are changed as well, going from the straight and simple ones of the past to the trick dogleg-shaped levers found on the Low Slinger semi-chopper Suzukis. The new levers require less reach to grab the front brake, and a new, rectangular front master cylinder and new brake caliper use more lever travel and less lever force to produce a given level of braking power. It’s a much better set-up than the front brakes on earlier GS Suzukis, which seemed okay until you had a chance to compare them side-by-side with those on the Honda CB750F. After that comparison, the GS seemed to demand an iron grip and much longer fingers for the same stopping power provided by the Honda with much less pressure and a shorter reach as well. In addition, the new Suzuki master cylinder’s cover is held on by screws, instead of being a screw-on cap. That lessens the temptation for curious young hands prone to mischief and also discourages the inquisitive owner from taking off the cap unnecessarily, possibly letting in water (which glycol-base brake fluid attracts and absorbs) at the same time.

The Suzuki stops pretty well, pulling up from 60 mph in 141 feet and from 30 mph in 34 feet, and the brakes still work when it’s raining. Before you whip out the tape measure and fire off a letter telling us how you can stop your GS550 quicker than that, we should add that stopping distance depends upon the pavement and tires as well as rider and brakes. The pavement patch we use for braking tests isn’t in the best of condition (a lot of polished little stones stick up out of the asphalt) but it’s the same for every bike we test. The 1977 GS stopped from 30 in 31 feet and from 60 in 119 feet, and we’re inclined to believe that the difference is in the rear brake and the tires. The standard-model GS550 tested in 1977 (like the current standard model) had a drum rear brake less prone to lock-up under hard braking. When the rear locks up, it makes the bike difficult to control under maximum braking and lengthens stopping distances as well.

The 1980 GS has new-style Bridgestone Mag Mopus tires unlike any we’ve seen before with the “Mag Mopus” designation. Suzuki spokesmen tell us that the new L303 (front) and S714 (rear) Bridgestones were fitted to the GS series after extensive testing, but we don’t think the Bridgestones are as good as the previously fitted IRC tires. The rear tire is very skittish under hard braking and we noticed a touch of front end chatter when pushing hard in turns.

But even so, it was while conducting braking tests at the local dragstrip and while tearing about mountain roads that we rediscovered why we liked the GS550 in the first place. Compared to an XS850 Yamaha and the Honda CBX tested at the same time, the smallest Suzuki Four was a dream to haul down from speed and to fling around the curves. It’s easy to toss around and change direction, and steers well in spite of its weight figures. It feels lighter than 467 lbs. and is stable and neutral. A head angle of 29° contributes to straight-line stability, and the GS is less affected than the CB750F Honda (27.5° head angle) at top speed by such things as rear tire wear. Yet because the GS has a 56.5 in. wheelbase (compared to the Honda’s 60 in.) it still turns.

It’s not perfect. Like everything else, the GS has its tradeoffs. On one canyon ride, the GS was blown all over its lane by sidewinds gusting down intersecting canyons; but in all fairness the only bikes that seem immune to that problem in that place are heavy motorcycles with high centers of gravity, like the Yamaha XS11 and the Honda CBX.

The suspension, although basically comprised of 1977 components, delivers excellent compliance and does a good job of soaking up repetitive bumps, such as concrete roadway expansion joints.

But when the Suzuki leaves the simple straights and smooth, massive sweepers of > the interstate for the cobby hairpins and decreasing-radius, blind-entrance, bumpriddled curves of the mountain back road, the shocks seem slightly underdamped on rebound, a condition which lets the rear end bounce. We think that the front end’s minimal chattering at the limit is caused more by the tire than the suspension because we’ve ridden earlier GS550s with different tires and not had a problem, and U.S. Suzuki spokesmen say that the suspension hasn’t been changed for 1980. The light shock absorber rebound damping which works so well on small, repeating freeway joints isn’t the hot tip for big bumps encountered while on the brakes or gas at the edge of traction, but then gofasters can buy accessory shocks.

Ground clearance is excellent, first limited by a peculiar retangular tab located halfway up the leading-edge of the sidestand on the left, and by the footpeg, exhaust collector and muffler hanger on the right. We didn’t drag the right side at all on the street, but we did touch the sidestand on the left. With the stands off and the bike on the racetrack, the peg and muffler bracket on the left joined the peg, exhaust collector and muffler hanger on the right in hitting the pavement.

Anybody intent on racing will be happy to know that the 550, as always, has needle roller swing arm bearings.

The seat is good, better than on earlier models, but the pegs seem too far forward in relationship to the handlebars.

The grips are still poor, with a ribbed design that eventually wears through thick riding gloves and raises blisters on the rider’s thumb-and-forefinger webs through thin gloves on long rides. The only thing that we can figure is that Suzuki got a bulk deal on 8.3 million pairs of the things and hasn’t run out yet.

The helmet lock is a hook hidden by the hinged seat, and was a matter of internal debate. Some of the riders like the hidden hook, on grounds that you can easily get two helmets on it, and some of the riders prefer separate locks, as used by Honda, because you needn’t dismount all your luggage just to secure the helmet. Suffice it that the Suzuki uses one system, the other brands use another.

The mirrors are fitted into rubber mounts and remain essentially clear throughout the rev range, even when the engine’s vibration peak (if you can call a Four’s vibration “peak” compared to Twins or Triples) at 4000 rpm makes the gas tank resonate. The rubber mounts do allow the mirrors to move ground, but not enough to distract the rider.

The sealed o-ring, endless chain should in theory reduce chain maintenance, since grease is sealed between the pins and rollers, but the Suzuki manual wants the owner to clean the chain with kerosene and lubricate it with 40 or 50w motor oil (not commercial chain sprays) every 600 miles. It seems that chain sprays contain propellants that make o-rings swell and eventually fail, yet the chain must be lubricated to prevent rust and avoid accelerated chain/sprocket contact-area wear. Knowing that, we’re not sure what the advantage of a sealed o-ring chain is, especially since 30 miles in the rain caused the chain on our test bike to tighten up to the point of having no slack at all. A long blast of (gasp!) chain spray loosened up the taut chain.

Anybody who has stood in driving rain trying to pour motor oil on a chain will appreciate why we used the spray. Anybody who has ever replaced an endless chain (which has no master link) will also understand why, if the 550 were ours, we’d install a conventional chain with a master link once the original equipment chain wore out.

And speaking of easy maintenance, the GS550 comes up short in a couple of other areas. When an errant rock knocked a hole in the headlight lens, we couldn’t understand why the mounting system for the sealed-beam headlight is as complicated as it is. Then there’s the matter of having to remove the carburetors to get at the cam chain tensioner.

Ah, the cam chain tensioner. It is automatic. Basically a large ball bearing, backed by a spring-loaded pusher, works against the tapered end of a shaft, which works against the tensioner shoe on the rear run of the cam chain. As the cam chain stretches and/or the tensioner shoe wears, the pressure of the spring-loaded pusher (which is mounted perpendicular to the main tensioner body) forces the ball bearing forward against the tapered tensioner shaft, which reacts by moving forward and pushing the tensioner shoe against the cam chain, thus taking up any slack.

In actual practice, very high revs can kick the tensioner and tensioner shaft back, making the ball bearing retreat and the spring-loaded parts back up. When that happens, cam chain tension goes all to hell and the valves bend, usually at 10,00010,500 rpm.

There are solutions. One, keep rpm well below 10,000 (the Suzuki redline is 9500 rpm).Two remove the manual lock screw and nut from the side of the tensioner, grind a point on an appropriate hex or Allen head bolt and install it (with a locking nut) instead, using silicone sealant to replace the stock -o-ring seal. Three, disassemble the tensioner and make the taper on the back of the main tensioner shaft steeper so it can’t back up in spite of the spring-loaded ball bearing lock system. Four, remove the tensioner assembly and send it to Kazuo Yoshima at Ontario Moto Tech, (where it will receive the above modifications and more), install it upon its return, and rev the GS as high as you wish.

The headlight on the GS is as good as the headlights found on other bikes of its size, but that illustrates the fact that most motorcycle headlights are inadequate for high-speed riding on dark country roads. The low beam on our GS was useless at speed for much more than allowing other motorists to spot the bike, and the high beam wasn’t much better.

The horn is worse. It isn’t loud enough, and a soft-spoken horn doesn’t do much good when an oblivious driver is pulling directly into your path. There are many motorcycles around with adequate horns. The GS550 isn’t one of them.

Horns, grips, even headlights can be easily changed and improved upon by a motorcycle owner. More difficult and expensive to alter is the basic fabric of the machine, it’s performance and handling and character. In those essential areas, the GS550 delivers. Considering that this is 1980 and bearing in mind the changes wrought by the EPA and NHTSA, the fact that the 1980 GS550 is better overall than any GS550 before it is nothing short of a technological miracle. 1 S3

SUZUKI

GS550ET

$2139