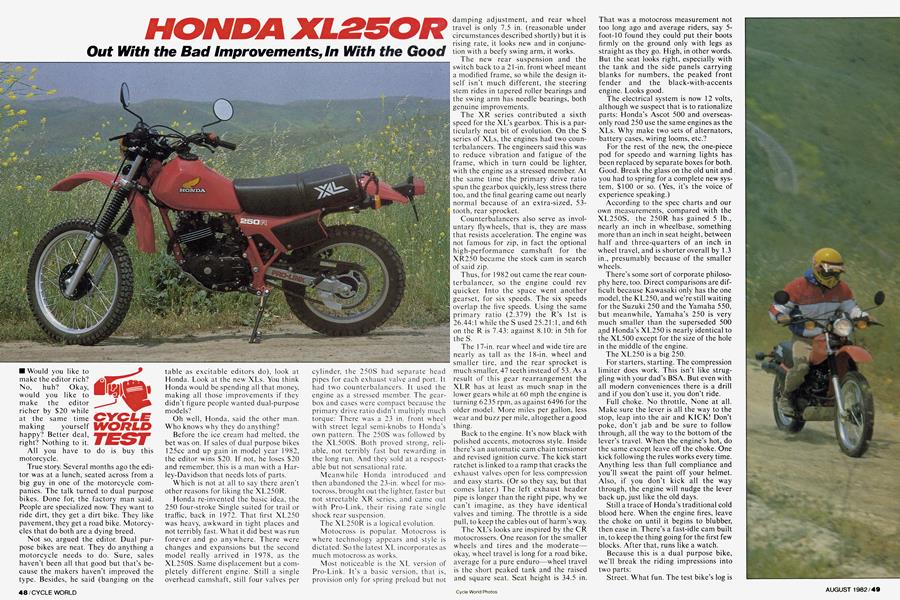

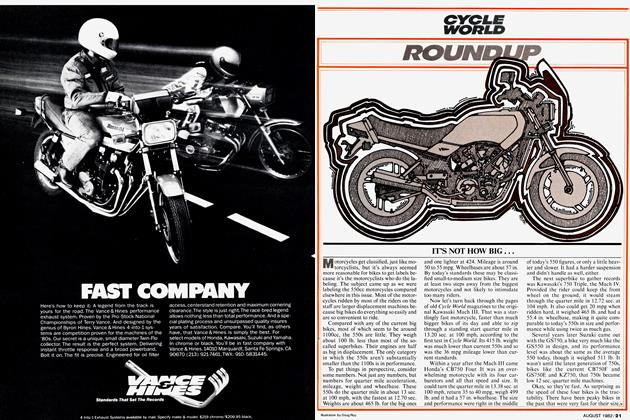

HONDA XL25OR

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Out With the Bad Improvements, In With the Good

Would you like to make the editor rich? No, huh? Okay, would you like to make the editor richer by $20 while at the same time making yourself happy? Better deal, right? Nothing to it.

All you have to do is buy this motorcycle.

True story. Several months ago the editor was at a lunch, seated across from a big guy in one of the motorcycle companies. The talk turned to dual purpose bikes. Done for, the factory man said. People are specialized now. They want to ride dirt, they get a dirt bike. They like pavement, they get a road bike. Motorcycles that do both are a dying breed.

Not so, argued the editor. Dual purpose bikes are neat. They do anything a motorcycle needs to do. Sure, sales haven’t been all that good but that’s because the makers haven’t improved the type. Besides, he said (banging on the

table as excitable editors do), look at Honda. Look at the new XLs. You think Honda would be spending all that money, making all those improvements if they didn’t figure people wanted dual-purpose models?

Oh well, Honda, said the other man. Who knows why they do anything?

Before the ice cream had melted, the bet was on. If sales of dual purpose bikes 125cc and up gain in model year 1982, the editor wins $20. If not, he loses $20 and remember, this is a man with a Harley-Davidson that needs lots of parts.

Which is not at all to say there aren't other reasons for liking the XL250R.

Honda re-invented the basic idea, the 250 four-stroke Single suited for trail or traffic, back in 1972. That first XL250 was heavy, awkward in tight places and not terribly fast. What it did best was run forever and go anywhere. There were changes and expansions but the second model really arrived in 1978, as the XL250S. Same displacement but a completely different engine. Still a single overhead camshaft, still four valves per

cylinder, the 250S had separate head pipes for each exhaust valve and port. It had two counterbalancers. It used the engine as a stressed member. The gearbox and cases were compact because the primary drive ratio didn't multiply much torque: There was a 23 in. front wheel with street legal semi-knobs to Honda’s own pattern. The 250S was followed by the XL500S. Both proved strong, reliable, not terribly fast but rewarding in the long run. And they sold at a respectable but not sensational rate.

Meanwhile Honda introduced and then abandoned the 23-in. wheel for motocross, brought out the lighter, faster but not streetable XR series, and came out with Pro-Link, their rising rate single shock rear suspension.

The XL250R is a logical evolution.

Motocross is popular. Motocross is where technology appears and style is dictated. So the latest XL incorporates as much motocross as works.

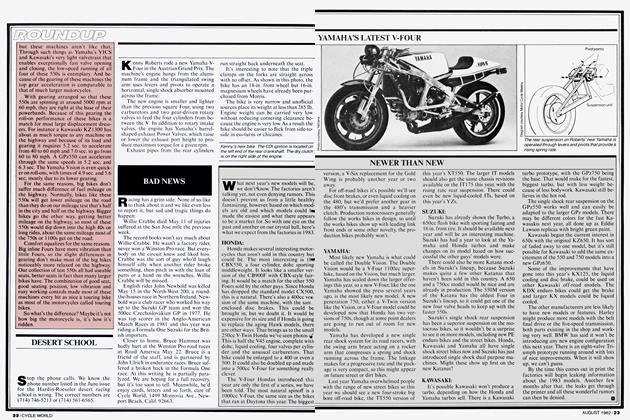

Most noticeable is the XL version of Pro-Link. It's a basic version, that is, provision only for spring preload but not

damping adjustment, and rear wheel travel is only 7.5 in. (reasonable under circumstances described shortly) but it is rising rate, it looks new and in conjunction with a beefy swing arm, it works.

The new rear suspension and the switch back to a 21-in. front wheel meant a modified frame, so while the design itself isn’t much different, the steering stem rides in tapered roller bearings and the swing arm has needle bearings, both genuine improvements.

The XR series contributed a sixth speed for the XL’s gearbox. This is a particularly neat bit of evolution. On the S series of XLs, the engines had two counterbalancers. The engineers said this was to reduce vibration and fatigue of the frame, which in turn could be lighter, with the engine as a stressed member. At the same time the primary drive ratio spun the gearbox quickly, less stress there too, and the final gearing came out nearly normal because of an extra-sized, 53tooth, rear sprocket.

Counterbalancers also serve as involuntary flywheels, that is, they are mass that resists acceleration. The engine was not famous for zip, in fact the optional high-performance camshaft for the XR250 became the stock cam in search of said zip.

Thus, for 1982 out came the rear counterbalancer, so the engine could rev quicker. Into the space went another gearset, for six speeds. The six speeds overlap the five speeds. Using the same primary ratio (2.379) the R’s 1st is 26.44:1 while the S used 25.21:1, and 6th on the R is 7.43: against 8.10: in 5th for the S.

The 17-in. rear wheel and wide tire are nearly as tall as the 18-in. wheel and smaller tire, and the rear sprocket is much smaller, 47 teeth instead of 53. As a result of this gear rearrangement the XLR has at least as much snap in the lower gears while at 60 mph the engine is turning 6235 rpm, as against 6496 for the older model. More miles per gallon, less wear and buzz per mile, altogether a good thing.

Back to the engine. It’s now black with polished accents, motocross style. Inside there’s an automatic cam chain tensioner and revised ignition curve. The kick start ratchet is linked to a ramp that cracks the exhaust valves open for less compression and easy starts. (Or so they say, but that comes later.) The left exhaust header pipe is longer than the right pipe, why we can’t imagine, as they have identical valves and timing. The throttle is a side pull, to keep the cables out of harm’s way.

The XL’s looks are inspired by the CR motocrossers. One reason for the smaller wheels and tires and the moderate— okay, wheel travel is long for a road bike, average for a pure enduro—wheel travel is the short peaked tank and the raised and square seat. Seat height is 34.5 in.

That was a motocross measurement not too long ago and average riders, say 5foot-10 found they could put their boots firmly on the ground only with legs as straight as they go. High, in other words. But the seat looks right, especially with the tank and the side panels carrying blanks for numbers, the peaked front fender and the black-with-accents engine. Looks good.

The electrical system is now 12 volts, although we suspect that is to rationalize parts: Honda’s Ascot 500 and overseasonly road 250 use the same engines as the XLs. Why make two sets of alternators, battery cases, wiring looms, etc.?

For the rest of the new, the one-piece pod for speedo and warning lights has been replaced by separate boxes for both. Good. Break the glass on the old unit and you had to spring for a complete new system, $100 or so. (Yes, it’s the voice of experience speaking.)

According to the spec charts and our own measurements, compared with the XL250S, the 250R has gained 5 lb., nearly an inch in wheelbase, something more than an inch in seat height, between half and three-quarters of an inch in wheel travel, and is shorter overall by 1.3 in., presumably because of the smaller wheels.

There’s some sort of corporate philosophy here, too. Direct comparisons are difficult because Kawasaki only has the one model, the KL250, and we’re still waiting for the Suzuki 250 and the Yamaha 550, but meanwhile, Yamaha’s 250 is very much smaller than the superseded 500 and Honda’s XL250 is nearly identical to the XL500 except for the size of the hole in the middle of the engine.

The XL250 is a big 250.

For starters, starting. The compression limiter does work. This isn’t like struggling with your dad’s BSA. But even with all modern conveniences there is a drill and if you don’t use it, you don’t ride.

Full choke. No throttle, None at all. Make sure the lever is all the way to the stop, leap into the air and KICK! Don’t poke, don’t jab and be sure to follow through, all the way to the bottom of the lever’s travel. When the engine’s hot, do the same except leave off the choke. One kick following the rules works every time. Anything less than full compliance and you’ll sweat the paint off your helmet. Also, if you don’t kick all the way through, the engine will nudge the lever back up, just like the old days.

Still a trace of Honda’s traditional cold blood here. When the engine fires, leave the choke on until it begins to blubber, then ease in. There’s a fast-idle cam built in, to keep the thing going for the first few blocks. After that, runs like a watch.

Because this is a dual purpose bike, we’ll break the riding impressions into two parts:

Street. What fun. The test bike’s log is

packed with notes about how nice this thing is in the city. Compared against the median road bike, or even the road-only Singles, the XL250 is a feather. It steers, banks, corrects, quick as a blink. It turns on even an inflation-shrunken dime. Wheelies (leave space here for that business about don’t try this at home, kids) are a snap of the throttle. For errands, you can’t beat it.

The open road is okay, perhaps even better than you think. The loss of one counterbalancer isn’t noticed. The engine buzzes, it’s a Single after all, but never to the point of annoyance.

There are two numbers here, one important, the other not.

The quarter mile time is there for the record. We all like to know what our bike’ll do. In this case it will keep up with traffic while encounters with the XL250 will not send Corvette and Ferrari owners slinking home for new plugs.

Forget the E.T. What matters here is that the engine feels quick. It’s willing and able. The six speeds and choice of ratios let the rider wind and shift without feeling abusive. (The tachometer is gone, but the speedo has the redline for each gear marked on its face so you needn’t actually be abusive.) There’s no stumble,

............

flat spot, clatter of valves or loss of breath. In its own way, like the Big Twins, this 250 Single makes feeling powerful as good as being powerful.

The other number, the one to remember, is mileage. An honest 70 mpg, observed, makes even the bogus EPA car numbers look wasteful. This isn’t economy run practice. Each test bike gets ridden with the traffic. That should help the big guns because they’re not off the pilot jets at traffic speeds, while the smaller engines in theory work closer to their stops. Even so, the XL’s 2.5 gal. tank gives a useful range of 150 mi. and then you get to watch strong drivers weep as you top off for less than three bucks.

Handling is entertainment. Just as turbochargers have not proven to be a substitute for displacement, so does wheel travel give comfort beyond air assist and compressor-adjusted suspension. Chuckholes, cracks, ridges and the like disappear. The high pegs and pipe and ground clearance mean no problem. Provided the rubber side is still down, you’ll never drag anything. The steering is fast and the weight can be tossed about, you can hang off or bank in . . . guys used to win road races with dual-purpose Singles and it’s easy to understand how.

The only major drawback is the seat, which is too much motocross for long rides. It’s square and narrow and tilts to-

ward the tank, fine when you need to slide forward for a berm, not so fine when you keep sliding forward all day. A lower, rounder seat would work better in this application, while making it easier to reach the ground. Passengers, though, liked the extra padding on their portion.

The bars are wide, too wide for the highway as they dictate an upright position that becomes tiring. If this was ours we’d hacksaw an inch off each end. The engine’s natural cruising speed is about 70 mph but sailing against the wind is tiring, so we settled for 65, the normal speed at which one needn’t live in the mirrors or get tickets. No great loss, but lower bars and a wider seat would be appreciated.

Dirt. One of our mottos is Testing In Context, so we didn’t enter the XL250 in motocross races or enduros. This is an explorer bike and/or a playbike. The XL250 defines the latter’s definition; you can ride out in the morning, just to look around and go anywhere your fancy leads you.

The tires are the key here. They almost deserve a chapter in themselves because they are in another sense the limiting factor. They must be certified for and work on the pavement, so Yokohama’s Y-969 tires have modest knobs, spaced to put rubber on the road and dig into the dirt. They do grip the pavement, in fact they’ll slide only because the XL cannot run out of ground clearance the way a road bike can. They even squeegee rain water, something full knobbies won’t do.

The combination makes the XL a fine slider. Not power slides, there’s not enough power for that. Instead it handles fireroads in style. Ride in, bank, set the suspension with the rear brake and around she goes with both tires sliding, just enough. The wider profile gives some float on sand despite the weight on the front tire; the XL will run even a medium deep wash in control. Likewise on rocks. Mud is something else. It quickly fills the spaces between the knobs.The front wheel slithers, the back one spins. We never actually got stuck, despite digging the rear wheel in to the axle, but there was always the feeling that the next bog would be the stopper. The XL250 isn’t the bike to ride during the spring thaw.

Suspension is enduro equipment. Spring rates and damping are on the light side, as they should be for a machine that isn’t supposed to go through Killer Whoops topped out in 6th. They will soak up the bumps and keep the bike in control when the drop is higher than it looked. The 21-in. front wheel makes a big difference here, as the XL no longer fights the rider in ruts. It steers accurately rather than quickly and the controllable

power lets the rider keep his intended line.

In sum, no vices. Limits. The tires aren’t knobbies, wheel travel isn’t motocross type and the overall weight can be tiring at the ragged edges. Keep within the limits, don’t ride faster than you can see and the mirrors and turn signals will live forever.

We return you now to the showroom. The XL250R will cruise at the legal limit, zip through the city and ramble down any trail the eye can follow.. The suspension works, the engine is bulletproof and even your father can maintain it.

The editor is already spending his winnings. 88

HONDA XL25O