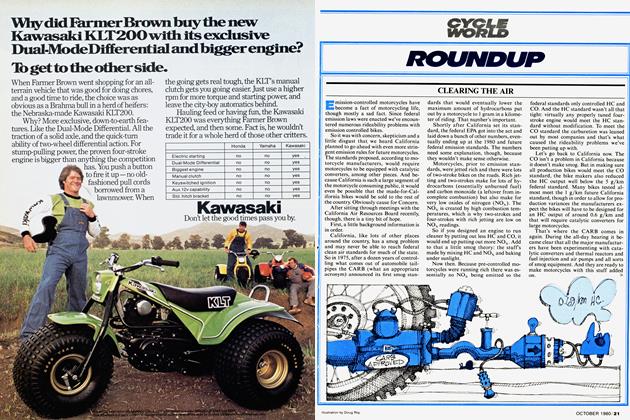

HONDA CB750C

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Honda's Best Selling 750 Gets More Flash for 1981

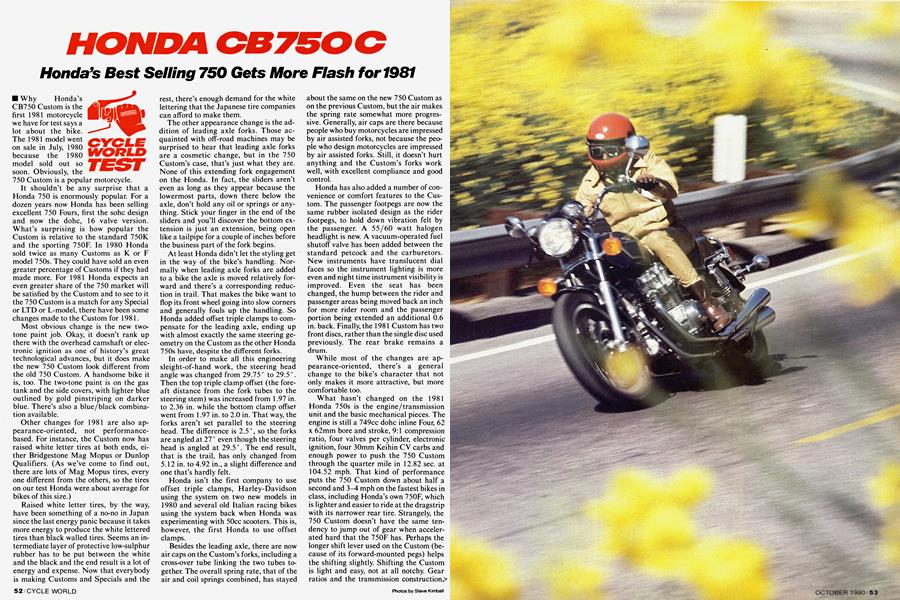

Why Honda's CB750 Custom is the first 1981 motorcycle we have for test says a lot about the bike. The 1981 model went on sale in July, 1980 because the 1980 model sold out so soon. Obviously, the 750 Custom is a popular motorcycle. It shouldn’t be any surprise that a Honda 750 is enormously popular. For a dozen years now Honda has been selling excellent 750 Fours, first the sohc design and now the dohc, 16 valve version. What’s surprising is how popular the Custom is relative to the standard 750K and the sporting 750F. In 1980 Honda sold twice as many Customs as K or F model 750s. They could have sold an even greater percentage of Customs if they had made more. For 1981 Honda expects an even greater share of the 750 market will be satisfied by the Custom and to see to it the 750 Custom is a match for any Special or LTD or L-model, there have been some changes made to the Custom for 1981.

Most obvious change is the new twotone paint job. Okay, it doesn’t rank up there with the overhead camshaft or electronic ignition as one of history’s great technological advances, but it does make the new 750 Custom look different from the old 750 Custom. A handsome bike it is, too. The two-tone paint is on the gas tank and the side covers, with lighter blue outlined by gold pinstriping on darker blue. There’s also a blue/black combination available.

Other changes for 1981 are also appearance-oriented, not performancebased. For instance, the Custom now has raised white letter tires at both ends, either Bridgestone Mag Mopus or Dunlop Qualifiers. (As we’ve come to find out, there are lots of Mag Mopus tires, every one different from the others, so the tires on our test Honda were about average for bikes of this size.)

Raised white letter tires, by the way, have been something of a no-no in Japan since the last energy panic because it takes more energy to produce the white lettered tires than black walled tires. Seems an intermediate layer of protective low-sulphur rubber has to be put between the white and the black and the end result is a lot of energy and expense. Now that everybody is making Customs and Specials and the

rest, there’s enough demand for the white lettering that the Japanese tire companies can afford to make them.

The other appearance change is the addition of leading axle forks. Those acquainted with off-road machines may be surprised to hear that leading axle forks are a cosmetic change, but in the 750 Custom’s case, that’s just what they are. None of this extending fork engagement on the Honda. In fact, the sliders aren’t even as long as they appear because the lowermost parts, down there below the axle, don’t hold any oil or springs or anything. Stick your finger in the end of the sliders and you’ll discover the bottom extension is just an extension, being open like a tailpipe for a couple of inches before the business part of the fork begins.

At least Honda didn’t let the styling get in the way of the bike’s handling. Normally when leading axle forks are added to a bike the axle is moved relatively forward and there’s a corresponding reduction in trail. That makes the bike want to flop its front wheel going into slow corners and generally fouls up the handling. So Honda added offset triple clamps to compensate for the leading axle, ending up with almost exactly the same steering geometry on the Custom as the other Honda 750s have, despite the different forks.

In order to make all this engineering sleight-of-hand work, the steering head angle was changed from 29.75° to 29.5°. Then the top triple clamp offset (the foreaft distance from the fork tubes to the steering stem) was increased from 1.97 in. to 2.36 in. while the bottom clamp offset went from 1.97 in. to 2.0 in. That way, the forks aren’t set parallel to the steering head. The difference is 2.5°, so the forks are angled at 27 ° even though the steering head is angled at 29.5°. The end result, that is the trail, has only changed from 5.12 in. to 4.92 in., a slight difference and one that’s hardly felt.

Honda isn’t the First company to use offset triple clamps, Harley-Davidson using the system on two new models in 1980 and several old Italian racing bikes using the system back when Honda was experimenting with 50cc scooters. This is, however, the first Honda to use offset clamps.

Besides the leading axle, there are now air caps on the Custom’s forks, including a cross-over tube linking the two tubes together. The overall spring rate, that of the air and coil springs combined, has stayed

about the same on the new 750 Custom as on the previous Custom, but the air makes the spring rate somewhat more progressive. Generally, air caps are there because people who buy motorcycles are impressed by air assisted forks, not because the people who design motorcycles are impressed by air assisted forks. Still, it doesn’t hurt anything and the Custom’s forks work well, with excellent compliance and good control.

Honda has also added a number of convenience or comfort features to the Custom. The passenger footpegs are now the same rubber isolated design as the rider footpegs, to hold down vibration felt by the passenger. A 55/60 watt halogen headlight is new. A vacuum-operated fuel shutoff valve has been added between the standard petcock and the carburetors. New instruments have translucent dial faces so the instrument lighting is more even and night time instrument visibility is improved. Even the seat has been changed, the hump between the rider and passenger areas being moved back an inch for more rider room and the passenger portion being extended an additional 0.6 in. back. Finally, the 1981 Custom has two front discs, rather than the single disc used previously. The rear brake remains a drum.

While most of the changes are appearance-oriented, there’s a general change to the bike’s character that not only makes it more attractive, but more comfortable too.

What hasn’t changed on the 1981 Honda 750s is the engine/transmission unit and the basic mechanical pieces. The engine is still a 749cc dohc inline Four, 62 x 62mm bore and stroke, 9:1 compression ratio, four valves per cylinder, electronic ignition, four 30mm Keihin CV carbs and enough power to push the 750 Custom through the quarter mile in 12.82 sec. at 104.52 mph. That kind of performance puts the 750 Custom down about half a second and 3-4 mph on the fastest bikes in class, including Honda’s own 750F, which is lighter and easier to ride at the dragstrip with its narrower rear tire. Strangely, the 750 Custom doesn’t have the same tendency to jump out of gear when accelerated hard that the 750F has. Perhaps the longer shift lever used on the Custom (because of its forward-mounted pegs) helps the shifting slightly. Shifting the Custom is light and easy, not at all notchy. Gear ratios and the transmission construction^

like the engine, are unchanged for 1981 on the Honda 750s.

Perhaps straight-line performance, as measured by dragstrip numbers, is slightly off the mark, but other measures of engine performance are superb. No matter how cold it gets, pull out the choke knob at the steering head and push the starter button and the Custom fires instantly. It can be ridden away immediately after starting with the choke knob pushed in after a few hundred yards. In a day when many bikes take five or 10 minutes of revving madly away at 4000 rpm before they’ll lunge out of the driveway, the Honda 750 is a real treat. Warm or cold,

the engine runs flawlessly. It idles smoothly, can lug away from a stop with the engine barely turning and take off gently without need of clutch abuse or throttle heroics. No stumbles or stalls or coughs or missing ever interrupted the 750 Custom.

Power and performance, for normal riding, is plenty. As it has been since its inception, the dohc Honda 750 is a bit cammy, taking off with a real surge over 6000 rpm, but it is perfectly content to run at lower engine speeds if the rider doesn’t care for instant acceleration. The only flaw of the engine is the vibration level. Inline Fours have natural torsional vibration and on the 750 Custom this is more apparent than it

is on most Fours. Having the rider’s footpegs connected to the motorcycle with the same bolt that fastens the engine to the frame may tend to conduct some vibration to the pegs. And the long handlebars may amplify the problem somewhat, but the end result is that the rider feels continual and irritating vibration particularly when the engine is spinning at about 5000 rpm, which happens to coincide with 65 mph.

Honda uses a rubber engine mounting system on the CB900 Custom which effectively eliminates most of the buzz, but company spokesmen say the rubber mounting doesn’t work as well with a chain drive bike and that the vibration level of the 750 is low enough not to need the rubber.

Comfort, vibration aside, is generally good on the Custom. The longer seating area is a step in the right direction and the peg, seat and handlebar positions fit together acceptably. Rather than have handlebars that stretch halfway back to the taillight, the Honda Customs use wide bars that don’t come back as far as those on other semichoppers. In fact, the actual hand position on the Custom’s bars is about the same as that of the Honda CB750F bars, only the Custom bars are bent at slightly different angles. While the seating position is not a problem, the seat still is. In an effort to hold down seat height, the seat has been made hard. Not just firm, but hard. Around town it’s no problem as one gets to move around a bit and not sit on the seat too long. But after an hour on the highway there are just not enough ways to squirm to relieve that pain-in-the-butt feeling.

Suspension compliance, particularly at the back of the bike, contributes to the relative lack of comfort. On our regular bumpy concrete freeway the 750 Custom bounced up and down more than any bike we’ve tested recently, its combination of spring rate and damping being wrong for the distance between expansion joints. On other roads it wasn’t as bad, but it was never comfortable, though the seat has a lot to do with that.

Honda pointed out that the 750 Custom uses new VHD (Variable Hydraulic Damping) shocks which are an improved version of the FVQ (Full Variable Quality) shocks used before. The actual design is the same with spring-loaded valves reducing rebound damping when the shock is moved quickly, as in riding over really rough roads. The overall effect is about the same.

Of course the Custom doesn’t use the higher quality, more expensive shocks that come on the 75ÓF, and it suffers because of it. The 750F suspension works better, not only for sporting riding, but for comfort as well.

The Custom also doesn’t handle as well as the 750F, but that’s why Honda makes the 750F. Large 16 in. rear tires aren’t conducive to good handling, having too

much sidewall area that can flex under cornering loads. But the Custom styling demands the 16 in. tire, so Honda uses it, knowing there’s a sacrifice in handling stability. Cornering clearance on the Custom is also less than that of the F, though about average with other bikes of its style. With the rear springs set at minimum preload the centerstand drags in moderately fast left and right hand corners. Set the spring preload higher, pump some more air into the forks and the cornering clearance increases, so the centerstand doesn’t touch down until the pegs are already scraping. The 750 Custom allows, maybe even encourages, that sort of riding because the steering is light and precise and overall stability of the machine is good, which is to be expected of a bike with a 61 in. wheelbase.

Looking at the bike, seeing the forks offset from the steering head, naturally makes the rider suspect the handling. Yet the only noticeable characteristic of the bike’s handling is the light effort it takes to turn the bike with the wide handlebars.

This is a bike to be looked at. That’s why all the chrome. It has chromed fenders and chain guard and covers over the rear springs and four chromed pipes and chrome covers on the sides of the airbox and a smooth-looking chrome mount for the chromed headlight shell. Compared with the other semi-choppers, the Honda Custom has a little more flash than some, and yet it’s a little more tasteful than others. The combination of flash and class, everyone agreed, was excellent. Even the gold wings above the gold Honda badge on

the gas tank didn’t bother anyone.

At least the Honda Custom has an adequate sized 4.4 gal. gas tank, which isn’t as large as we’d like to see, but better than some other semi-chopper peanut tanks. Coupled with the 46 mpg fuel mileage, the 750 can run a total of 200 mi., or 152 mi. before hitting the 1.1 gal. reserve.

There isn’t much to be criticized on the 750 Custom. It may vibrate a little too much and need a better seat; those things could be said about most motorcycles. About the only flaw the Honda has that other bikes don’t have is a strange characteristic in the brakes. The discs have a tendency to warp slightly with use, making the brake lever move in and out when the brakes are held on lightly. It’s a characteristic we’ve noted on Hondas for about

three years now, one which Honda says they’ve fixed with different brake disc machining, though our test bike still had the problem.

A loud squeal accompanied any stopping and occasionally the front discs would squeal even when the brake wasn’t pulled. Stopping distances, braking power and brake control were all very good, despite the noise and pulse.

Going into its third year, the dohc Honda 750, whether Custom, K or F is still a wonderful motorcycle. It’s powerful, runs without complaint, handles well, is moderately comfortable and, if our longterm 750F is any indication, practically unbreakable. Despite the slight concessions to style, the Custom is one motorcycle we all enjoyed riding. 13

HONDA

CB750

$2998