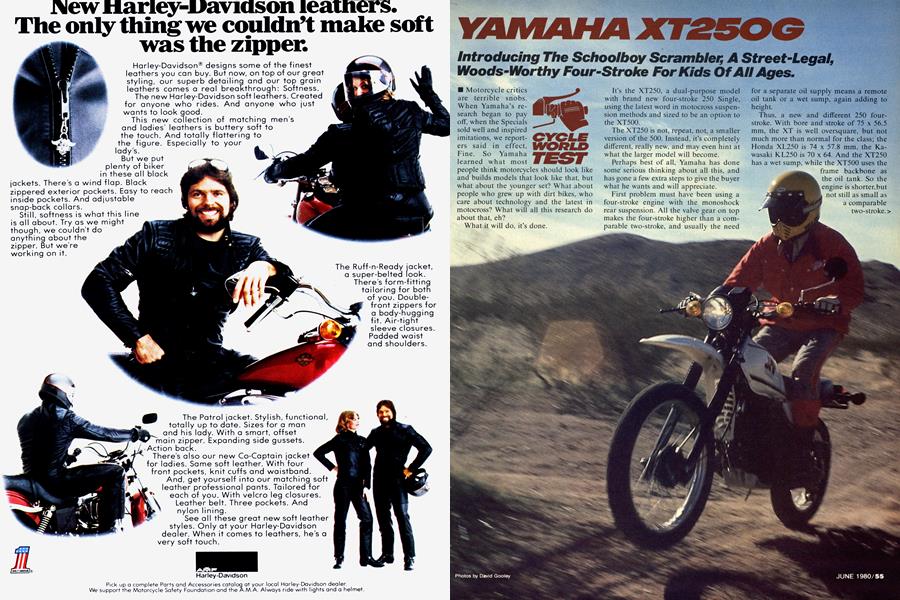

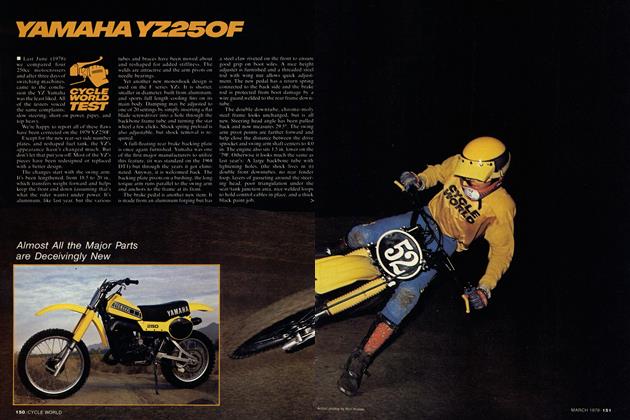

YAMAHA XT250G

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Introducing The Schoolboy Scrambler, A Street-Legal, Woods-Worthy Four-Stroke For Kids Of All Ages.

Motorcycle critics are terrible snobs. When Yamaha’s research began to pay off, when the Specials sold well and inspired imitations, we reporters said in effect, Fine. So Yamaha learned what most people think motorcycles should look like and builds models that look like that, but what about the younger set? What about people who grew up with dirt bikes, who care about technology and the latest in motocross? What will all this research do about that, eh?

What it will do, it’s done. It’s the XT250, a dual-purpose model with brand new four-stroke 250 Single, using the latest word in motocross suspension methods and sized to be an option to the XT500.

The XT250 is not, repeat, not, a smaller version of the 500. Instead, it’s completely different, really new, and may even hint at what the larger model will become.

Perhaps best of all, Yamaha has done some serious thinking about all this, and has gone a few extra steps to give the buyer what he wants and will appreciate.

First problem must have been using a four-stroke engine with the monoshock rear suspension. All the valve gear on top makes the four-stroke higher than a comparable two-stroke, and usually the need for a separate oil supply means a remote oil tank or a wet sump, again adding to height.

Thus, a new and different 250 fourstroke. With bore and stroke of 75 x 56.5 mm, the XT is well oversquare, but not much more than normal for the class; the Honda XL250 is 74 x 57.8 mm, the Kawasaki KL250 is 70 x 64. And the XT250 has a wet sump, while the XT500 uses the frame backbone as the oil tank. So the engine is shorter.but not still as small as a comparable two-stroke.

Yamaha’s solution was a new frame, with the engine as a stressed member. The single front downtube runs to the front engine mount, and stops. There’s a tightly shaped aluminum skid plate but no bottom tubes, which gains an inch or so of ground clearance. The cylinder head ties to the backbone, taking advantage of the lack of room, as it were. And the cases, transmission, etc., are small, just as the YZ two-strokes are small, so the XT engine fits within the dimensions available for it, without undue seat height and with as much ground clearance as the dirt-oriented suspension demands.

In terms of power and tuning, the 250 is fairly normal. There’s a single overhead camshaft, working one intake and one exhaust valve via rocker arms. Clearance is adjusted at the valve stem tip. by wrench and screwdriver. Compression ratio is 9.2:1, which allows regular or no-lead gas. Carburetor is a 28mm Mikuni. with accelerator pump so there’s no lag when the throttle is opened despite lean jetting for the EPA.

There are some unusual items. Carrying on Honda’s technique, the 250 has a compression limiter, a start lever-linked arrangement that lifts the exhaust valve off its seat. There’s a sight gauge for oil level, the oil filter is serviced from the right side, much less mess, and the lefthand cover is one piece, for the alternator and the countershaft sprocket and is made of plastic.

The major change, though, is that the 250 has a counterbalancer. Same idea as the Honda Singles and the old Yamaha 750 Twin, but a much different technique. The XT/TT/SR250 has one counterbalancer, gear-driven off the crank. It’s a porkchop-shaped weight, and it’s even got a damper built into the hub.

Sound engineering. A Single is difficult to balance, in fact it can’t be done perfectly. The piston and connecting rod go up and down, while the weights on the crank go round and round. Thus, even if the weight of one equals the weight of the other, the forces generated will be different because the paths taken are different. In the past, engineers allowed for this by making the balancer weigh a percentage of the piston/crank, balanced to 60 percent or 70 percent as the saying was. The forces going around restrained, but didn't exactly balance, the forces going up and down.

But with the separate balancer, rotating the other way, you have a mass that acts to cancel the mass that’s there to equal the back and forth, putting it all too simply.

And it seems to work. Something of a bonus in this model, as people who buy bikes with off-road potential usually tolerate vibrations far more severe than the tiny tingle of this engine. Honda, with a double balancer system, says it’s fitted to their engine because the vibrations would otherwise fatigue the stressed-engine frame.

Yamaha doesn't have that in mind. Instead, the system is used here for the benefit of people who'll buy the road-only SR250. Yamaha has that one targeted toward new riders, people who may not know that vibrations are part of the fun. So they smooth it out and because it’s easier to keep the same engine for all models, the XT and TT hardly shake enough to put your toes to sleep.

An elaborate way to go. but it works. On the Honda XLs. and on the XT250. Is this much work worth it? Hard to say. The previous generation of four-stroke Singles, and the Kawasaki and Suzukis of the present. don’t have counterbalancers and although the Honda and Yamaha 250s are smoother, and less tiring on the long run, the differences are minor. Riders who aren't out there with notepads likely would get used to whichever system their factory had.

Where this does make a difference is on the bigger Singles, the 500s, where the Honda is markedly less vibratory than the Yamaha. In 1978 Honda introduced the new 250, with compression limiter and counterbalancers that weren’t needed on that engine but which paid off when the new 500 was unveiled. So here’s Yamaha with a second-generation four-stroke 250 Single carrying the same features, also not really needed. Wanna bet when the second Yamaha 500 gets here, it has the compression limiter and counterbalancer?

The 250 is a basic engine. Yamaha has experience with multiple-valve heads, built the first modern production ones, in fact. But they say now all you get for multiple valves is complexity. For the revs used by production engines, one valve per side is plenty.

Seems to be the case here. The Yamaha 250 is rated at 21 bhp at 8000 rpm. identical to the Kawasaki 250 and a fraction more than the Honda 250. However, the Yamaha is markedly strong. Torque peaks at 14.5 lb.-ft. at 6000 but the factory dyno charts show it’s cranking out better than 12 lb.-ft. at 2500 and doesn’t fall below that until 8500. Pulling power, if you can say that about a 250 Single.

As proof of the chart, the Yamaha will dust off the other two at the drags. Part of that may be due to lighter weight, but the Yamaha must have better power all the way because it’s geared higher, that is, it turns less than 6000 at 60 mph while the other two are spinning 6500. And it’s more efficient, as we’ll see when we get on the road.

All those computers that spend most of their time messing up your bank statement and writing letters supposed to come from real people are about to redeem themselves.

As part of the space program. American scientists did incredible things with training computers to measure and analyze.

Much of this work is available to our allies. There’s a think tank in Japan that adapts technology like this, so Yamaha worked with them and came up with programs that can feed stress into components and tell how much is being absorbed, how much is doing damage and where the damage is coming from and going to.

What all these banks of tape and blinking lights do is tell the Yamaha engineers just how strong a component must be, which is another way of saying how light they can make it.

The XT250 frame was built with this program. It’s also built around the monoshock.

Wave of the future, in some circles. Kawasaki and Honda have followed Yamaha’s lead in motocross, and Yamaha, Honda and Kawasaki all use a variation of the single shock rear suspension in Grand Prix road racing. No question that the idea works. And in Europe, where road riders follow road race trends, Yamaha sells monoshock roadsters styled like TZs.

In America, they don’t. One might suspect that the monoshock is used on the XT250, just as it is on the ITs and DTs, because it’s on the championship YZ motocrossers and the dirt-oriented rider tends to figure that if it works at Unadilla, it’ll work for him.

No matter. The designers have done a good job getting the four-stroke engine into the frame, and of putting the frame and suspension around the engine. As with the latest YZs, the front of the XT backbone is a large, single tube, feeding the suspension load into a well-boxed steering head. There are two smaller tubes bracketing the shock and going to the rear downtubes and engine mounts, with a short tube triangulating the backbone and front tube and a head steady between engine and backbone. Aft of the shock, there’s no more frame than is needed to carry the seat.

The XT gets its own monoshock, instead of sharing with the YZs, DTs and ITs. The XT version is short, but unlike the motocross models the body is aft of the spring, making the heavy end unsprung weight, and there’s no separate reservoir because the XT isn’t intended for serious high speed work. Although you can vary spring pre-load, it’s not easy. Spring position is controlled by a large nut, locked by a smaller nut, so you need wrenches and some determination to experiment with the setting. Damping is set at the factory. There’s no option for changing and because the body contains oil and nitrogen under pressure, the owner is severely warned not to fiddle with the unit.

The rear downtubes bolt to the back of the engine and the rear of the cases has a mounting hole that carries the bolt for the swing arm pivot, which saves space and weight and puts the pivot nice and close to the countershaft sprocket, i.e., chain tension doesn’t vary much with wheel travel. There’s a spring-loaded tensioner fitted just in case, though.

The swing arm itself is the usual Yamaha double Vee, with two tubes bracing the upper and lower portions just in front of the rear tire. The arm is mild steel and looks small. Good to know the computer has told the designers how light the arm can be. The XT may share this part with some other model, as the XT250 is sold as a solo vehicle only, no strap or passenger handle, yet the swing arm has tapped lugs for passenger pegs.

Front suspension is good of stanchion tubes and sliders, springs and oil and damper valves. No air caps, and if you wish to turn the front end, you swap fork oil or springs or add caps or slide the tubes up and down in the clamps. The XT250 is built to a price, for the non-race rider. The axle mounts ahead of the tubes, though we suspect that feature and the fins on the sliders are there mostly because that’s how it's done in motocross. Drums brakes, leading and trailing shoes, at both ends. The> XT lacks the speed of the big YZ, so the super double leading shoe front brake on that juggernaut isn’t needed here.

Tires are new, from Bridgestone. More computers here. The tread is aggressive, as much more than Honda’s Claw-Action street/dirt tread as that tread goes beyond the older block-pattern trials universal. We’re told Bridgestone has devised test programs for the size, shape and location of the knobs, which lets them go beyond plain square blocks.

The front tire is a 21, and the rear is a 17. One reason is that you get more suspension, as the 4.60-17 is actually as tall as the 4.10-18 you’d expect on this size machine. Less wheel, more tire to flex and absorb bumps and grab the ground. Also, the shorter spokes are stronger for their diameter.

Suspension travel. 8 in. in front, 7 in. rear, is as close to the Honda XL250 as we can measure and as with that bike, the travel seems the best compromise between rough-terrain speed and seat height.

The air filter is also balance. This is a light-duty-dirt model, and isn’t expected to race through the dust. So the filter is smaller than the ones on the ITs and YZs. It’s simply a slide, with coarse foam on one side, finer foam on the other. You undo the wing nut, pop off the cover and slide the filter out. Wash it. oil it and zip. back it goes. Never even have to touch the surface. It couldn’t be easier, so the relative lack of filter area doesn't matter.

Instruments are a fair trade. There's a speedometer and three warning lights. No tachometer. In exchange, the odometer has instant reset, no winding down every time you top up. which is a bargain by us. Turn signals are tucked away on the bars in front, and have flexible stalks at the rear. We dropped the XT in the course of the test but didn’t bend or break anything, so the right precautions have been taken.

The front fender has the long aft section with vents first seen on the Yamaha MX models and later used by Maico. The idea is that the extra length keeps mud off the engine, while the vents keep cooling air flowing through. Sounds good. Too bad they didn't offer the same protection at the back, where the motocross-style flare does nothing toward keeping road spray and muck ofl'the back of your jacket. Whoever tests before production must wear clothes provided by the factory.

Then again, maybe not. Yamaha’s test riders must have scorched the legs in their riding suits about the time we did the same to our suits. The XT250 has its exhaust pipe tucked well away from the rider’s knee, and shielded. Then there's a plastic cover over a metal cover over the front part of the muffler, just below the rear edge of the seat. No way this one can even touch the rider’s clothes, much less burn through.

The brochures list the 250's fuel capacity as 2.1 gal., but we could only pack 1.9 into the tank. Either figure is not as much as we'd like. In the woods, the XT will go twice as far as the tw'o-strokes. but on the road, even at the gratifying rate of 70 mpg. you'll switch to reserve at 115 miles or so.

Weight. That’s the secret here, and Yamaha has made giant little strides on that. In test conditions, half a tank of gas. the XT250 tips the scales at 267 lb. Nearly 50 lb. less than the XT500, hurray.and 111b. less than the XL250. good, but somehow, thinking about those computers, the plastic covers, the spindly-looking rear sprocket, we'd hoped for more lightness. But as the tuner says, lightness costs money.

Some of the dimensions, by the way. are misleading, although not deceptive.

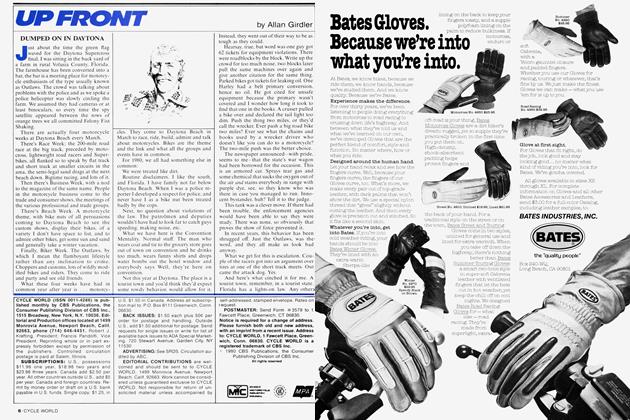

The XT250 feels smaller than it is. First impression was that it's shorter than the others in class but the wheelbase is 55.5 in.. compared to 54.7 for the XL250 and 55.1 for the KL250. It feels lower, but the static seat height is 33.25 in. and the XL's is 33.2 in.

So it feels smaller, but it's not. First, the XT has lower handlebars, and they’re narrower and closer to the seat. Second, the rear spring is softer, and so is the narrower seat, so when you climb on. the feeling is that of a smaller bike, one sized for the younger rider, the not-quite-adult, the opposite sex or even the man who just doesn’t want a 500.

None of which is wrong, or even bad. Being slightly scaled down, in feel if not on the spec chart, does create confidence. Yamaha’s marketeers are good at asking the right questions and building what the customer wants.

The engine justifies the effort. With the compression limiter, you kick and the engine fires up. Won't bite in a hundred years. The choke includes a fast idle, so you dial on warm-up and the engine goes pup-pup-pup until you have your helmet on. Starting from cold sometimes takes a dozen kicks, though.

On the road, the XT works best for errands and short runs. The wide power band allows fairly wide gearing and the 1st gear that pulls you up impossible hills off road winds the engine to peak almost too quickly on the pavement, but the shift and clutch and throttle are light, there’s no flat spot and the 250 winds happily through the gears. Nice exhaust note, too, much better than the SR500 although we don’t know why. Rain grooves don’t bother the tires, the ride is acceptable and the XT will dart through gaps, avoid the careless and track well, right up to top speed.

Where it becomes fairly busy. Balancer or not, the engine begins to feel strained at more than 60. so w hen you get out on the open road and the semis come thundering past, not so nice. And the narrow seat, motocross look again, is soft but also narrowand an hour or so is plenty. Sure, people have gone thousands of miles on motorcycles smaller and rougher than this, but going Portland to Miami on the XT250 while the XS11 sits dusty in the garage is one heck of a hard way to get into the Guiness Book of Records. Figure 50 miles a day. Skipping through the traffic and listening to the super engine is what the XT250 carries a license plate for.

And underlying this, the reason Yamaha came out with the dual-purpose 250 Single in the first place, is the knowledge that you can ride to and through the woods.

At a respectable pace.

With due consideration. Power is no problem at all, as the 250 is tuned just right for casual plonking about. Given traction it will haul the bike up any grade the fun rider is likely to tackle. The brakes put some superbikes to shame on the pavement and they do as well on the dirt, power without risk of locking the wheel.

Worded carefully, the XT250 steers as slowly as does the XL250, that is, slower than the ITs and other serious enduro bikes. The XT has a long wheelbase, it isn’t light when compared to the serious twostrokes and it plain can’t be zapped through the turns in motocross fashion. What it does is steer more easily than an XL250 or the XT500. The 21-in. front tire, and less sheer weight, get the front end around without muscle. The tires work well on hardpack, good as those gumball trials jobs on rock, and not too well in sand, where they’re not wide enough to float and don’t have the right pattern to bite.

Suspension is set for the novice and the casual. The travel is enough, but it’s used up quickly. Landing from two feet or so up will bottom both ends, not hard, and the jolt won’t throw the bike out of line, but the bump is there, the XT’s way of telling you that’s high and far enough.

Damping is also soft. This may be why the spring rate is soft too. Unlike the earlier motocross monoshocks, the back end won’t kick if you hit a bump on a trailing throttle. The rear wheel will get behind the sequence of the ground and if the going is really rough, the back of the XT gets jumpy, going at angles while the front wheel is pointed straight.

Like the other dual-purpose 250 fourstroke with stressed engine as part of the frame and with stanchion tubes and swing arm that look not stout enough for high speed, the XT250 can be pushed into loadings the chassis can’t handle. This isn’t a question of vices or inadequate construction. What the XT is not is a motorcrosser with lights.

Great on Sunday afternoon, though, as a family vehicle, the best way to get back into the empty places, and to go fast enough to learn how it’s done.

Back to research. If Yamaha has figured there are people out there who want a fourstroke Single with motocross technical features, one that looks good and fits the kid who can pay for it and who needs to get around town while waiting to tackle the whoops on Saturday, then Yamaha has the right machine to sell ’em.

YAMAHA XT250G

$1479