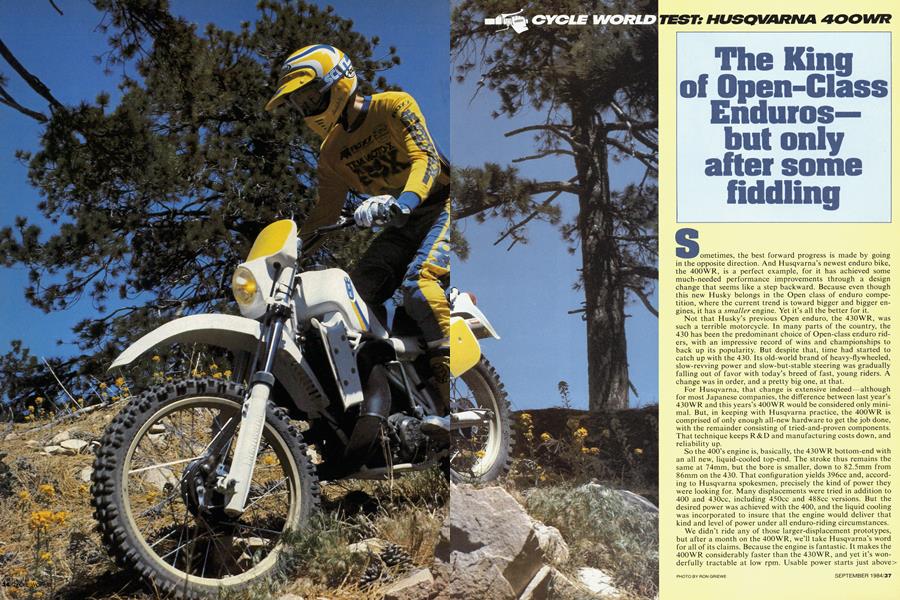

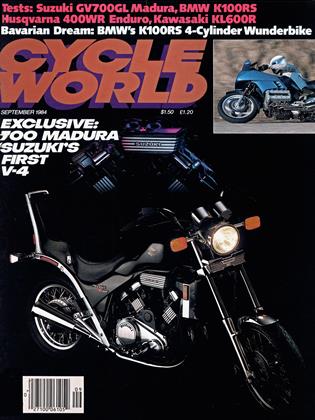

HUSQVARNA 400WR

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The King of Open-Class Enduros— but only after some fiddling

Sometimes, the best forward progress is made by going in the opposite direction. And Husqvarna’s newest enduro bike, the 400WR, is a perfect example, for it has achieved some much-needed performance improvements through a design change that seems like a step backward. Because even though this new Husky belongs in the Open class of enduro competition, where the current trend is toward bigger and bigger engines, it has a smaller engine. Yet it’s all the better for it.

Not that Husky’s previous Open enduro, the 430WR, was such a terrible motorcycle. In many parts of the country, the 430 has been the predominant choice of Open-class enduro riders, with an impressive record of wins and championships to back up its popularity. But despite that, time had started to catch up with the 430. Its old-world brand of heavy-flywheeled, slow-revving power and slow-but-stable steering was gradually falling out of favor with today’s breed of fast, young riders. A change was in order, and a pretty big one, at that.

For Husqvarna, that change is extensive indeed—although for most Japanese companies, the difference between last year’s 430WR and this years’s 400WR would be considered only minimal. But, in keeping with Husqvarna practice, the 400WR is comprised of only enough all-new hardware to get the job done, with the remainder consisting of tried-and-proven components. That technique keeps R&D and manufacturing costs down, and reliability up.

So the 400’s engine is, basically, the 430WR bottom-end with an all new, liquid-cooled top-end. The stroke thus remains the same at 74mm, but the bore is smaller, down to 82.5mm from 86mm on the 430. That configuration yields 396cc and, according to Husqvarna spokesmen, precisely the kind of power they were looking for. Many displacements were tried in addition to 400 and 430cc, including 450cc and 488cc versions. But the desired power was achieved with the 400, and the liquid cooling was incorporated to insure that the engine would deliver that kind and level of power under all enduro-riding circumstances.

We didn’t ride any of those larger-displacement prototypes, but after a month on the 400WR, we’ll take Husqvarna’s word for all of its claims. Because the engine is fantastic. It makes the 400WR considerably faster than the 430WR, and yet it’s wonderfully tractable at low rpm. Usable power starts just above> idle and builds smoothly and cleanly to about 3000 or 3500 rpm; and at that point, a second powerband kicks in and sends the 400 rocketing off in a rush, winding out like a factory-ported 250cc motocrosser. The transition between the lower and upper powerbands is fairly smooth if the throttle is only partially open or if the twistgrip is rolled open rather than being dumped wideopen. If you do the latter, as our testers soon found, the quickrevving motor leaps into its higher-rpm powerband with a vengeance, often with the front wheel airborne and the rider hanging on for dear life. After a few of those on a tight trail, you soon learn to be more gentle with the throttle.

Once the rider adapts to that transition, the dual powerbands prove very useful in a variety of trail conditions. The lower revs allow the 400 to torque through mud, over tree roots, around slippery off-camber turns and through tight corners about as tractably as the 430WR would. But when the woods open up and there’s room for some good, old-fashioned acceleration, the high-rpm powerband lets the 400 roost down the trail at least as quickly as something with a full 500cc of displacement. And at any rpm, the engine responds crisply and immediately, which lets the rider loft the front wheel over any reasonable trail obstacle just by snapping the throttle open a little further.

A possible benefit of the 400WR’s smaller displacement is that engine vibration isn’t as severe as it is on the 430WR (or especially on the 500WR, a limited-production, 488cc enduro model introduced early in 1984 as an alternative for powercrazed woods riders). The 400’s vibration generally is of a higher frequency than the 430’s, but is not as strong; and at lower revs, the 400 is quite a lot smoother. Of course, the 400 generally revs higher at any given trail speed than its 430cc counterpart did, due to having less displacement and lower (higher numerically) primary and final-drive gearing; but overall, the new Husky vibrates less than any Open-class enduro bike we’ve ever tested.

It also ought to run cooler, what with it being the industry’s first liquid-cooled Open-class enduro bike. A crankshaft-driven water pump circulates coolant through the cylinder and head, into dual radiators mounted behind the single front frame downtube. That radiator location caused a problem in the routing of the exhaust system, though, by forcing the fattest part of the pipe to be far to the rear and in an area where it can interfere with the rider’s left leg. The side numberplate protects the rider from most of the heat; but the panel does not conform closely to the pipe’s bends, so it makes the bike extremely wide in the area just above the footpegs—so much so that the only way to stand on the footpegs is to assume a bow-legged stance. Also, sliding forward on the seat for a sharp righthand turn causes the rider’s left knee to contact the unshielded area of the pipe, which can heat that part of his leg to the point of being painful.

It says"Made In Sweden."but it runs and feels like something built on the other side of the world-like Japan, for instance.

A local Husky dealer has come up with a simple fix for this problem. He removes the numberplate’s front mounting screw and spacer, then uses two plastic ties to secure the plate—one tie up front to pull the plate in against the pipe, another under the left side of the seat to pull the plate in against the frame. The inside of the plate is lined with a high-temperature rubber material, so it won’t melt when drawn in against the pipe; and although the 400WR still will be fat enough in the midsection to require a slight cowboy-like stand-up riding position, the improvement is worthwhile.

So, too, is it worth a 400WR owner’s time and trouble to improve the front suspension action. As delivered, the Huskybuilt front fork is too harsh, and so it jolts the rider’s hands and forearms on big or abrupt bumps. We changed fork oil on our test bike, swapping the stock 15-weight for lighter 10-weight (but still using the recommended volume of 15 ounces); we also popped the fork seals loose, coated their lipped areas with oil to help the tubes slide through them more easily, then reinstalled them. After that, the fork worked nicely. It was exceptionally compliant and able to soak up all sorts of trail bumps, from the small chops to the biggest whoops and jump landings.

A similar sort of damping problem exists at the rear of the 400WR, but the remedy for this one is not so simple—or inexpensive. According to Husqvarna’s tech people, “some” 400WRs (they couldn’t say which ones or how many) are delivered with too much damping in their dual Ohlins rear shocks. The bikes that have this problem aren’t hard to identify when ridden; they’ll buck and hop and pound in a manner uncharacteristic of recent Husqvarnas. The company has issued a service bulletin that outlines a cure for this condition, but a private citizen probably won’t be able to do the work himself, since it involves the use of special tools and some knowledge of how a shock works. Our test bike was one of the affected units, so we took the shocks to a Husky dealer who, for $50 in labor and $ 12 in parts, reworked them according to the bulletin.

Once that damping problem was cleared up, the 400WR’s rear end behaved admirably. The shocks were then able to gobble up just about every kind of bump we could run under the> rear wheel. The rear end seldom bottomed, and it never allowed the back of the bike to kick, either sideways or up and down.

As soon as we got the suspension sorted out, we were able to confirm Husqvarna’s claims that the 400WR is not a typical Husky in the way it steers and handles. The bike is impressively quick and responsive through the tightest of trail-riding conditions—and not just quick for a Husky; it’s quick compared to just about any full-size dirt bike there is. Some of that is due to the engine being so quick and responsive, some is caused by the 400 having more weight on the front wheel than Huskys of recent years have had. But the steering’s sharpness is mostly a result of the quickest steering geometry (a claimed 28.5-degree steering head angle and 5.2 inches of trail, which is about 1.5 degrees and 0.5-inch less than on the 430WR) used on a stock Husqvarna in a long time.

After riding the bike, however, after experiencing how nimbly it flicks around sharp turns, how quickly it changes direction when threading through tight woods, how willingly it can be flopped over into a corner, we decided to measure the head angle and trail for ourselves, for the improvement in steering action seemed much more drastic than Husky’s numbers would indicate. And sure enough, we found that the claimed steering angle is about right, but that the 400 actually has around 4.8 inches of trail, significantly less than what the company claims.

Whatever the numbers are, though, the 400WR certainly is the most nimble Husqvarna to come along in years. In some situations, in fact, it handles almost as quickly as, say, a Honda CR250R motocrosser, which is one of the most agile dirt machines to be found anywhere. And yet the 400 doesn’t suffer any significant instability problems as a result of its quick steering. It’s not quite as dead-stable, obviously, at high speeds as a 430WR or practically any other recent Husqvarna, but neither does it wiggle or twitch when trucking along at or near its 85mph top speed.

If a rider prefers slightly slower steering, maybe for a desert enduro, he can drop the Husky’s 40mm fork tubes down about half an inch inside of the triple-clamps. That’s a particularly good idea if the 400WR is going to be used in a lot of deep sand, for the bike doesn’t like to go where it’s pointed under those conditions with the tubes in their highest position. The 400 doesn’t feel heavy in deep sand, just awkward. And that’s surprising, because the 400WR actually is 11 pounds heavier than the 430WR. The trick is in the steering, which makes the bike feel 10, or 20 pounds lighter.

It also feels rather tall and unusual until you get used to it. The handlebar is low, which causes the rider to lean forward somewhat; but once you get used to that position, you find that it’s part of the reason why the 400 carves around tight corners so precisely. And the Husky feels taller than it actually is because the seat is padded with extremely hard foam that barely compresses when sat upon. Neither does the firmness of the seat do anything to add to the 400’s comfort level, although the bike is quite good in that respect, especially after the suspension is properly set up.

Too bad we can’t say as much about the 400WR’s drum brakes, which are all too typical of late-model Husqvarna brakes. The rear brake is adequate if not spectacular, but the front is marginal, especially for a double-leading-shoe type. Hauling the 400 down from speeds over 50 or 60 mph calls for an awful lot of lever pull; and when wet, both brakes go away altogether, and don’t return until they’ve been dragged for a long, long time thereafter.

We also have little good to say about the 400WR’s silencer/ spark arrester, which is of the same design that Husqvarna has been using for years—and that has been troublesome for just as long. The arrester is comprised of a fine-wire screen and a cone with numerous small holes, all of which clogs up easily with carbon and thus needs constant cleaning. We replaced the stock unit with an Answer Products silencer/arrester and eliminated the problem without sacrificing anything in performance.

That’s nice to know. But it also brings us to a puzzling conclusion about the 400WR: We like it. A lot. Enough to own one and race it, in fact.

You probably wouldn’t have guessed that on your own, seeing as how we’ve registered so many complaints here about numerous parts of the 400—its shocks, brakes, seat, spark arrester, numberplate and, to a certain extent, front fork. Those all would be legitimate complaints on any enduro bike, and they're right next to unacceptable on a $3200 enduro bike.

Except. Except that once the fixable problems of that group are taken care of, the 400WR is a magnificent enduro machine, one that ought to be able to elevate your trail-riding speed a notch or two the first time you ride it. The bike is incredibly fast, exceptionally nimble and uncommonly forgiving.

But it’s also seriously flawed—although none of those flaws have anything to do with the engine, which is the best part of the entire motorcycle, despite being smaller than its predecessor. Still, we can’t wholeheartedly recommend a bike with so many out-of-the-crate shortcomings to everyone interested in an Open-class enduro bike; we can’t urge anyone to spend top dollar for a so-called “professional” competition bike knowing that they’ll also have to invest considerable time and money to get it working properly. Nope, we can't do that. All we can say is that if you do choose to buy a 400WR and sort out its problems, you just might end up with the most enjoyable Open-class enduro bike you can buy.

Wait. Make that the most enjoyable enduro bike you can build.

SPECIFICATIONS

$3195

HUSQVARNA

400 WR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

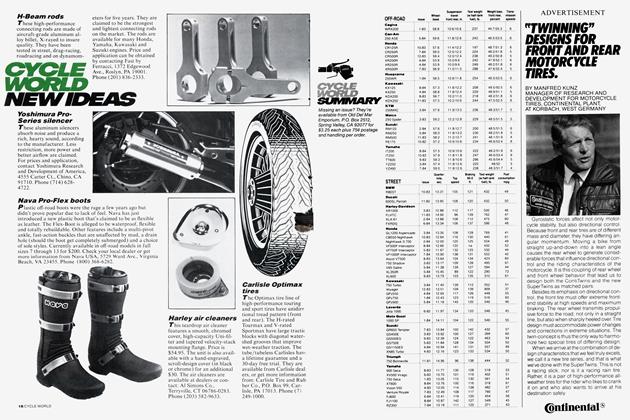

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Features

FeaturesThe Widow

SEPTEMBER 1984 By David Edwards -

Features

FeaturesLong-Term Test: Harley-Davidson Fxrs

SEPTEMBER 1984