KAWASAKI KS420-A2

CYCLE WORLD TEST

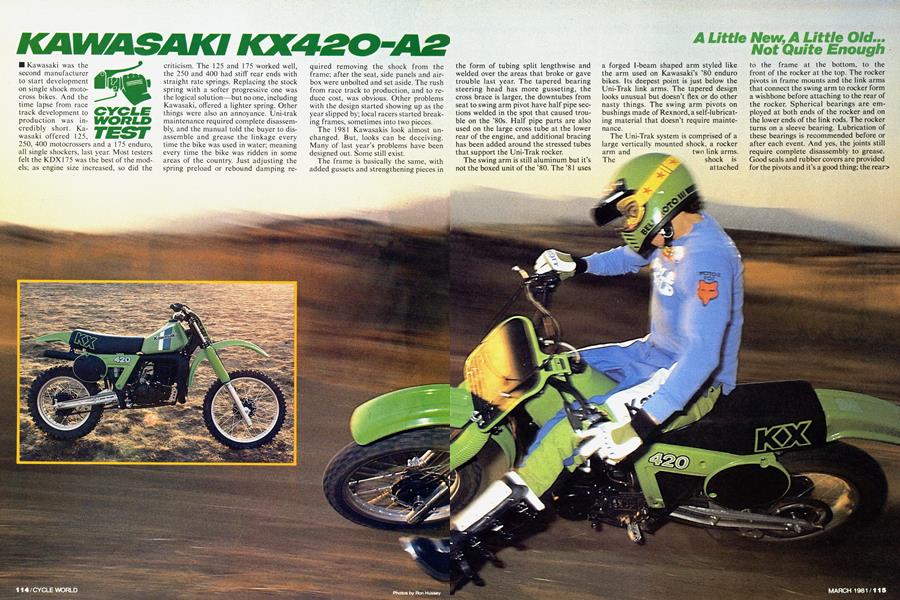

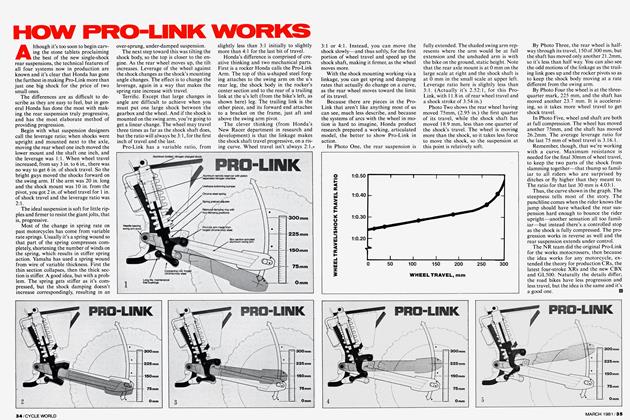

Kawasaki was the second manufacturer to start development on single shock motocross bikes. And the time lapse from race track development to production was incredibly short. Kawasaki offered 125, 250, 400 motocrossers and a 175 enduro, all single shockers, last year. Most testers felt the KDX175 was the best of the models; as engine size increased, so did the criticism. The 125 and 175 worked well, the 250 and 400 had stiff rear ends with straight rate springs. Replacing the stock spring with a softer progressive one was the logical solution—but no one, including Kawasaki, offered a lighter spring. Other things were also an annoyance. Uni-trak maintenance required complete disassembly, and the manual told the buyer to disassemble and grease the linkage every time the bike was used in water; meaning every time the bike was ridden in some areas of the country. Just adjusting the spring preload or rebound damping required removing the shock from the frame; after the seat, side panels and airbox were unbolted and set aside. The rush from race track to production, and to reduce cost, was obvious. Other problems with the design started showing up as the year slipped by; local racers started breaking frames, sometimes into two pieces.

The 1981 Kawasakis look almost unchanged. But, looks can be deceiving. Many of last year's problems have been designed out. Some still exist.

The frame is basically the same, with added gussets and strengthening pieces in the form of tubing split lengthwise and welded over the areas that broke or gave trouble last year. The tapered bearing steering head has more gusseting, the cross brace is larger, the downtubes from seat to swing arm pivot have half pipe sections welded in the spot that caused trouble on the '80s. Half pipe parts are also used on the large cross tube at the lower rear of the engine, and additional bracing has been added around the stressed tubes that support the Uni-Trak rocker.

A Little New, A Little Old... Not Quite Enough

The swing arm is still aluminum but it's not the boxed unit of the '80. The '81 uses

a forged I-beam shaped arm styled like the arm used on Kawasaki's '80 enduro bikes. Its deepest point is just below the Uni-Trak link arms. The tapered design looks unusual but doesn't flex or do other nasty things. The swing arm pivots on bushings made of Rexnord, a self-lubricating material that doesn't require maintenance.

The Uni-Trak system is comprised of a large vertically mounted shock, a rocker arm and two link arms.

The shock is

JÊk attached to the frame at the bottom, to the front of the rocker at the top. The rocker pivots in frame mounts and the link arms that connect the swing arm to rocker form a wishbone before attaching to the rear of the rocker. Spherical bearings are employed at both ends of the rocker and on the lower ends of the link rods. The rocker turns on a sleeve bearing. Lubrication of these bearings is recommended before or after each event. And yes, the joints still require complete disassembly to grease. Good seals and rubber covers are provided for the pivots and it's a good thing; the rear>

wheel constantly assaults the system with mud, sand, rocks or whatever. The excellent owner's manual outlines maintenance procedures on the Uni-Trak system and gives the tightening torque for reassembly.

Adjustments on the Uni-Trak suspension have been simplified for '81. Damping adjustments are made by turning a knob at the top of the shock body. The knob is recessed into the top of the shock body and requires removal of the side panel and use of a small screwdriver. But it's all easier than it sounds. The knob is marked from one to four with Roman numerals and clicks when the number is centered in the window. Number one is the lightest rebound damping, number four is the heaviest. The manual still recommends removing the shock from the frame for spring preload adjustments. We found it unnecessary. A drift punch and hammer will easily and quickly do it. Either way, make sure the threads on the shock body are clean. Otherwise it's possible to strip the aluminum threads. Right, the shock body is aluminum this year. And it's rebuildable. This feature also makes oil changing and tuning with different weights of oil possible. Again, the procedure is outlined in the manual.

The shock spring is progressive this year. And the rate is right for the bike.

Forks are made by KYB and have 11.8 in. of travel. Stanchion tube size is 38mm. Most other manufacturers have gone to larger, 41 or 43mm, stanchions for '81. The Kawasaki's air/oil/spring forks use a leading axle lower leg. Both stanchion clamps have double pinch bolts and the top has rubber damped handlebar pedestals.

Plastic parts on the KX are unchanged for '81. The tank holds 2.4 gal. of premix and long motos will use all of it. The front fender does a good job of keeping goo off the rider and the stiffening ribs keep it from drooping into the tire when laden with mud. The rear is also ribbed but it's on the short side and the rider's back occasionally gets roosted as a result. The right side number panel didn't fit well on our test bike. The top didn't tuck under the seat rail tube as it was designed to do. Another complaint is the plastic gas cap. The cap incorporates a recessed vent spout, a neat idea but the vent hose is made from a hose with a thin wall and the recess around the spout is equally small. If the vent hose falls off, as they frequently do, normal gas line hose won't fit. The problem could be easily fixed by casting the grove in the cap a little wider.

We complained about last year's air cleaner; it was too large for the airbox,

eliminating much of the available filtering surface. The '81 has a shallower filter that cures the problem. The airbox is a good design that incorporates breathing holes in areas that are protected from water splash and the cover is a male/female joint that keeps out water and crud.

Brakes, wheels, spokes and rims are unchanged. The rear brake is smooth and positive. The front, rated as great until other manufacturers brought out double leading shoe models, doesn't have the sheer stopping power of the Honda CR450R or Yamaha YZ465H.

The Kawasaki 420, actually a 422, won't win any drag races against the Honda or Yamaha either. We had a Honda CR450R and an '80 YZ465G handy, so some head-to-head drags were conducted. The Kawasaki lost by six bike lengths every time. Roll-ons from about 20 mph between the three bikes proved the 420 equally slow; the other bikes will instantly jump a bike length ahead of the KX and then continue to pull away.

Externally the KX420 engine looks longer and larger than a YZ465, CR450R or RM400. The cases are big, the countershaft sprocket is too far from the swing arm pivot and the cylinder isn't boreable.

If the Electrofusion-coated aluminum bore surface becomes worn or damaged, a replacement cylinder is required. The 420 uses a large clutch and has primary kick starting. The start lever is a beefy looking steel part with a ribbed boot contact surface. The placement is a little high, like almost everyone's. We experienced trouble with the kick lever the first ride; it bent down and back. Once bent, starting became difficult with the starter's boot constantly sliding off the lever. The big Kawasaki 420 engine is a shaker with no lowend power, no top-end power, and brief mid-range power. Vibration is numbing to the rider's hands and arms. Long motos are almost out of the question, we couldn't find a rider who could hold on to the bars long. After checking the engine mounting bolts for tightness, we contacted a Kawasaki rep. The rep had broken-in our test bike and remembered. “It's normal, just got through breaking in another one and it feels the same,” was his reply.

The heavy vibration gives the illusion of power from just above idle, but it's a false impression. We say just above idle because

the 38mm Mikuni isn't equipped with an idle screw. The carburetor isn't even tapped for one! Unless the throttle cable adjustment is tightened up so the cable holds the slide open a little, the bike will constantly die when the throttle is rolled off. Damn annoying when entering a fast, whooped turn.

Gear selection is very important on the 420. The powerband is narrow for an open bike and the engine bogs if the rider doesn't keep the tranny in a low enough gear for the condition at hand. Shifting is quick and no one missed a shift or complained about the ratios. But the cheap steel shift lever is another matter. The knurled steel end folds as it should but due to poor placement of the shift shaft, (it exits the case behind the chain), the lever has to be routed down, under and back up to get around the chain. The first bend, down under the chain, has another piece of metal welded to the outside of the bend for added strength but the lever still has a flimsy feel and it looks terrible. And the lever height can't be altered. Sure, the shaft is splined, but the design limits movement. If moved down, the lever hits the frame when down shifting. Moved up it hits the chain when upshifting. The rider has to adjust to the stock placement. Sad. It's a shame to see such an afterthought shift lever next to the beautiful forged aluminum footpegs. They have sharp tops with the outermost point a little higher than the rest and good return springs. The peg on the right also lives next to a crude lever. The steel brake pedal is too short. The pedal end hits the operator in the ball of the foot, making it difficult to use with much control.

Steering precision and control are also poor on the big KX. The KX420 rider has three choices when cornering; make a square MX-type turn, use a berm or slide half mile style. The bike works well if cornered with one of the above styles. If the corner is littered with rocks or other obstacles requiring a ride-through type turn, be prepared to be scared. The KX has a head of its own and takes the line it likes. Make the ground sand and the rider's fright intensifies. The KX420 is the worst motocross bike we have ever ridden in a sand wash. It bounces off both banks, seems to hit every rock and every bush. And things get worse in twisty washes; square turns are the only way the rider can maintain any kind of control.

Whooped trails change the character of the bike. It'll charge down rough fast trails at breakneck speeds although steering control is still marginal; the steep 28° rake, 23.3 in. swing arm, and poor front tire work against the small fork stanchions. The handlebars don't dance around but the front wheel does. Wheelies are almost out of the question; the rider has to constantly correct and use lots of body english to keep the bike from falling over sideways or slamming back to the ground. Balance is off, and it feels like the weight of the engine has moved to the forks anytime the front wheel is lofted.

The up-dated Uni-Trak rear end works

well. Rebound damping is easily adjusted and the four settings give just about any degree of damping desired. We liked it set on number one, the lightest setting. The preload setting was stiffer than we liked so we softened it. One complete turn on the adjuster ring changes the preload by 35 lb.-ft. and the spring length by 2mm, so it's best to go slow and only change the setting one turn at a time. We liked it best when backed off two complete turns. The variable rate spring is right-on. Small bumps are smoothed yet the rear doesn't bottom harshly on bad ones.

Kawasaki claims the front forks are unchanged. We've liked the KX forks the past couple of years but the '81 seemed harsh. The book recommends using 15 weight oil with the level set at 180mm from the top of the tube, and 4 psi of air pressure. We followed the tuning chart in the manual and spent several hours adjusting the forks to our likes. First we lowered the oil level to 200mm with 15w oil. Next we changed to 10 weight oil. Finally, five weight Kal-Gard oil at the 200mm level suited us. We kept the air pressure at 4 psi throughout. The harshness disappeared and smooth, compliant fork action resulted.

Like many motocross racers, the 420 doesn't have a fold-up side stand. Most racers take them off anyway. A prop stand is delivered with the KX. It fits over a frame rail just under the swingarm pivot, an area that's usually coated with chain lube. If the stand is placed carefully and used on a hard surface, it'll just barely do the job. If bumped or used on a soft surface, the bike will fall over.

None of our crew liked the riding position of the KX. The seat is high, the bars low. It's a fall-over-the-bars feel that's easily cured by replacing the bars with higher ones.

Frankly, we expected more from the second year 420. It's slow, heavy, spooky to ride, and hard to maintain. And the heavy engine vibration makes the bike unacceptable for rides that last over 30 min.

KAWASAKI KX420-A2

$2099