CARB JETTING

Things The Factory NeverTold You About Making Your Carb Work Right

The new owner of the used Suzuki RM370 was disappointed. The bike was clean and straight and didn't look abused or neglected. The original owner sounded as if he knew what he was doing. But the first time the new owner rode the bike, it coughed and blubbered. He went to an older friend, who suggested they consult a mechanic who tunes motocross engines.

As they were rolling the RM down the ramp, the new owner remembered. They could skip checking the carb, he said, because the first owner had already jetted it.

The older man and the mechanic looked at each other, rolled their eyes to Heaven and said, with one voice, “Uh oh.”

And that's what the problem proved to be. Carb jetting is a fine, not-quite-black art, a straightforward procedure entangled from one side by good intentions and from the other by lack of information.

Most of the time carburetors work well, without troubles. But because they are so easy to reach and because the idea of gas and air being mixed through all those little holes seem easy to understand, home mechanics tend to be all too willing to fiddle with the carb while not checking the ignition which, by the way, is far more likely to cause that elusive miss.

That's the good intentions. The lack of information comes because most owner and shop manuals avoid all mention of modification. They give good stuff on how to check the stock carb on a stock engine, but forgo advice on what to do when you've made a change elsewhere and must change the carb to suit.

Why make changes? Most carbs are right for the engine as the engine was delivered. Juggling jets or swapping for large carburetors with no other changes, is foolish.

But there's also a need for carb modification. Typical circumstances could be: A big-bore kit or different camshafts. More displacement means more air so you'll need more fuel. Camshafts change timing, that is, breathing, and that can make a difference in what the carbs must feed the cylinders.

Low restriction exhaust. Although many aftermarket pipe makers now design so the new system will work with stock intake parts, sometimes they put the engine just beyond the best mixture. For racing, of course, no such limits exist so you'll almost certainly have to rejet to suit the exhaust.

Low restriction air filters. They usually move air more easily, so more air flows. As with pipes, many filters will work fine with carbs untouched, but some won't and you may need to change jets to get the performance gain the filters will deliver.

Carb swaps. True, it says earlier that changing carbs usually doesn't work. But sometimes it does. If you trade your Keikin for a Mikuni, or the Keihin that came with your new XL250 for the similar-butlarger Keihin from the old XL350, you'll need to tailor the carb to its new job.

Racing, with emphasis on the dirt. Factories jet for most conditions or for average conditions, such as sea level, temperate climate. If you live at higher elevations, 4000 ft. above sea level and up, or where the humidity or normal temperature are higher or lower than average, the engine may work better with changes. Dirt machines are more highly tuned and stressed, which makes them more demanding of just the right mixture anyway.

Plain corrections. Right, most engines work fine as they come. But as the rules get tougher, it's more likely that individual engines will be not quite right. They may stumble off idle or surge on cruise or starve at wide open throttle even though everything is properly adjusted.

Or it could be all of the above. You may need to juggle jets, and to know how, and to know when it's been done well.

The subject of this essay is how to make those changes.

First, a brief review of basics. At the most simple a carburetor is a section of pipe. Near its center is a narrow part. That restriction speeds the air flow through the pipe, reducing air pressure. The pressure change causes fuel to flow from a bowl into the pipe, via a series of holes. There's also a throttle to control the amount of airfuel allowed into the engine.

In fact the whole thing is much more complicated than that, but for now we know enough to move to the next step, the motorcycle carb.

Brand names don't matter here and each brand and type may vary in some way, i.e. some have accelerator pumps and some don't, but again in general there are two kinds of carburetors used on modern bikes.

One, the slide throttle. This has a slide, actually more like a piston, and it's moved up and down by a direct connection with the twist grip. The piston is a throttle; as it goes up and down it controls the incoming

air. It also controls fuel mixture because fixed below the piston is a needle that moves in a jet, which is more like a hole through which fuel flows.

Two, the CV carb. The throttle is a butterfly valve. The piston of a CV carb is separate from the throttle, not linked, and its position is controlled by air flow. The CV piston also has a needle. As air flow increases the piston goes up, the needle comes farther out of the jet and fuel flow increases as well. The extra parts and the separation of piston and throttle are because when you whack the throttle full open, there's a lag in the fuel-air flow and the engine starves or stumbles. The flowcontrolled piston damps this. It doesn't immediately go up and that maintains air velocity across the jets for that vital fraction of a second. The slide throttle carburetor uses a carefully shaped leading edge of the slide to do the same thing, and it's usually jetted richer to begin with to handle the same situation.

Why the two types and which one works better is a subject for another time, assuming the debate can be settled—it's been going on for 40 years or so.

What matters to us here is that each type uses the same general methods of metering fuel, so our outline applies to both.

SYSTEMS

Main jet. As you'd guess, the main jet is the principal source of fuel to the air stream. The main jet does its work mostly (we'll get to that part shortly) at wide open throttle. Critical for us here, the main jet can be removed, and replaced, and the jets come in different sizes.

Needle. As mentioned the needle rides below the slide or piston and fits into the needle jet. The needle is a restriction. The deeper it is in the jet, the less fuel can flow into the air stream. Needles are usually tapered, sometimes they're a double taper, that is, both at the tip and in the main section. Some models of carb offer a choice in needle diameter and taper. You can get one with a steep shoulder or one that's more gradual. The British Amal offers this in intimidating variety and some of the old tuning books listed which needle with what cam, main jet and ignition advance curve.

But that's more adjustment than we need. More common and more useful here will be the option of raising or lowering the needle relative to the piston. Formerly nee-: dies were held in the piston with a clip, and the needles came with a choice of slots for the clip. Up and down in seconds. But the EPA has closed that easy street for some bikes, another topic for later.

Needle Jet. The needle jet is the long jet the needle slides up and down through. It's usually made from brass and drilled crosswise with many small holes. The needle jet's function is metering the amount of fuel around the needle. Some needle jets also have a discharge nozzle attached to the top of them. Some carburetors have the nozzle separate from the needle jet. The nozzle protrudes into the carburetor throat where air passes over and around it. The passing air is broken by the nozzle and the turbulence draws fuel through the needle jet, around the needle. Different nozzle heights effect fuel flow differently, and offer another tuning dimension. Some carb manufacturers, Mikuni comes to mind, make dozens of different needle jets. Trying to tune a highly modified engine might require trying several different needle jets and needles before the engine is spot on. Of course, several days time might also be required.

Pilot jet. Sometimes called the slow running jet, this could also be called an idle jet, or a transition jet. It's smaller than the main jet and usually is sited upstream from the main jet. The pilot jet controls mixture as the engine moves off idle and carries the load until the needle and main jet take over. It also can determine how easy or hard an engine starts.

Miscellany. Carburetors have scores of other parts. There are the fuel float, with its own needle and seat; the choke or enrichener; and the idle speed adjustment. But while all these are important, and each must be working right if the engine is to run right, they are not usually adjustable in the sense of actual tuning to match other changes.

Back to basics, briefly. Carburetors have main jet, needle, needle jet, slide cutaway (or damped piston) and pilot jet because mixture demands change with engine (or rider) demands, that is, a lot. One system can't do it all.

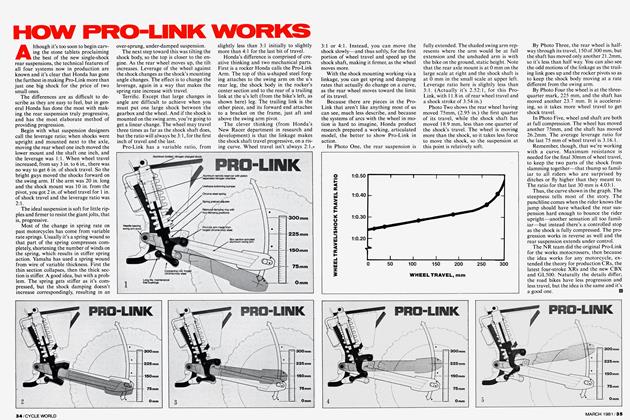

Instead we have a progression. Working from the bottom, the pilot jet is in control when starting and from idle to V» throttle. The position or cutaway of the slide or piston assist from '/s to 'A throttle, and during initial acceleration. The needle and needle jet rules from lA to 3A throttle and at cruise, and the main jet controls mixture from 3/4 to wide open. However, these divisions aren't absolutes. A great deal of overlap between the different functions takes place. A larger main jet might cause richness in the mid-range and raising the needle might cause rich running at the top of the revs, etc.

This progression is vital. Keep it handy, and use it as a guide.

The Law

Until recently, tuning your engine was a matter of parts and practice. Then we got the Clean Air Act. Because the lawmakers don't know nuthin' 'bout machinery they assumed controlling emissions would be a

matter of adding some not-yet-invented smog-guzzling gadget to downtube or firewall. So they wrote laws forbidding tampering with smog control devices.

But the engineers met the rules by modifying carbs and ignition, for the most part, meaning that the carburetors and ignitions are smog control devices. Federal law prohibits their modification by persons working for pay. The owner can make changes. Some states also prohibit modification by anybody.

Thank goodness we had the Constitution before Consumer Protection was a gleam in Ralph Nader's eye. The manufacturers cannot tell you how to make changes. But the free press can. And will.

It's also worth noting that although there is little or no enforcement of the rules, we cannot give permission for owners to modify. We've heard that some shops will give advice while the owner does the wrenching, but we don't know how that would hold up in court. In short, you know the rules and you make your own decision.

Of course none of the laws applies to dirt bikes, race bikes or to road bikes built prior to Jan. 1, 1978.

PARTS

Your best friend here works behind the parts counter. You're going to need various sizes of main jet and pilot jet. Depending on make and model and amount of engine modification you may also need a slide, needle jets, needles, and nozzles although we'll try to avoid that. And you may also need some minor bits, like small washers. Not least, have a shop manual for your machine. This is a general outline and the details as to where your main jet is, or how the needle attaches to the piston, depends on the engine under study. A good carb manual dealing with the brand carburetor involved is also valuable.

The parts man must be a good one. Some carbs, Mikuni for one, have enough jets behind the average counter to overwhelm the novice. Keihins are less available, Bings and Amals have plenty of parts but you need a dealer in European or English bikes to get them, Dellortos likewise.

The parts man helps here because sometimes the jets and needles and slides interchange and sometimes they don't. Only the expert can tell you that the pilot jet from a 26mm Keihin won't fit the 28mm Keihin, or that Mikunis for Suzukis will interchange between street and dirt but the dirt Mikuni for a Suzuki probably isn't the same as the one for the same size dirt Kawasaki.

The really tricky business comes with late model road bikes. The catalogs used to list richer and leaner options. Now, only leaner high-altitude jetting is offered, if any other jetting is listed. Usually it isn't.

You have to rely on expert help and street smarts. There is no richer main jet for Honda XL250s. But there is one for the old CB750A, and it's the same carb. You can't buy richer main jets for a 1980 Kawasaki 650. But the mains from a 1980 KZ750 will fit, and they're two steps richer.

We don't know it all. But as those exam-> pies show, if you find a good parts man, you and he can work it out nicely.

DOING IT

Begin with three rules.

1 ) One step at a time.

2) If you're wrong, be wrong on the side of rich.

3) Carbs don't read magazines.

Rules 1 and 3 are because of the system

overlap mentioned earlier. The book says the pilot jet signs off beyond Vx throttle and the main jet comes in at % throttle. But in action there's more overlap than the book says, and the change may occur before or after the chart predicts it. We'll be working from top speed down. The best way is to get the main jet right, working one size at a time and only on the main jet. A needle position that works with the wrong main can mask that mistake until it's too late. And if you change too far you can skip over the right size. Yes, it takes longer, but one step per test is the only way to be sure.

Rule 2 saves engines. If it's too rich, it will blubber and foul plugs and finally choke to a halt. But fresh plugs and leaner jets and all's well. Too lean and you can melt your engine before you know it's wrong.

Rule 3 saves heartbreak. Your engine and carburetor don't know what's supposed to work. They only know what does work. If the main jet controls down to half throttle, accept it. If the engine sounds as if it needs a larger pilot and runs super with a leaner pilot, use the leaner pilot. Experiment until it runs best, Grab the baby and let the bathwater go down the tube.

Finally, here we go. You have your new collector pipes or air filter or stroker kit installed and the engine runs rough.

There are two ways to test for mixture, good and better. The good is by ear and seat-of-pants. If the engine sags and stumbles with no pattern as you open the throttle, it's probably lean. If it goes bu-bu-bubrooommm, a regular stutter until it clears up and jumps forward, it's too rich.

Leanness at cruise and full power feels as if the engine's running out of gas, which in a way it is. With too much gas it will blubber and pop. You can almost hear the excess banging and burning out the exhaust.

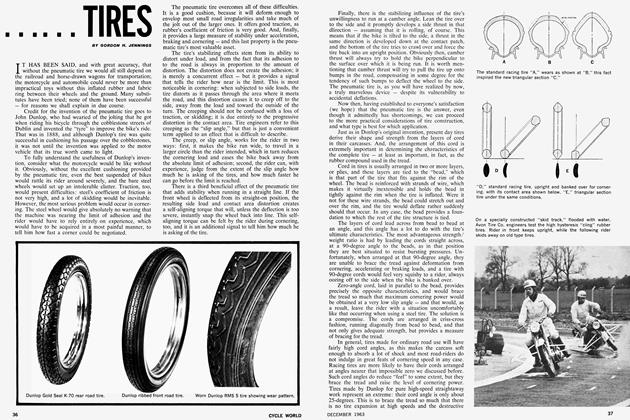

The better way to test is with spark plug checks. Your manual will have pictures of how a plug tip looks with the mixture lean, correct or rich. Or the spark plug companies will supply a pamphlet showing the same thing in color. Reading plugs is an art in itself but for now, we need to know that too rich is sooty black and too lean is blistered white and correct is grey or brown.

Actually checking the plugs may require initiative and effort. What you need is a way to run the engine under several conditions, mostly involving load and/or speed. For small engines, it's easy. All it takes is a flat stretch of ground for dirt bikes, an open mile of highway with maybe a headwind for 250cc and less road bikes.

Big enduro models or road-going superbikes and touring machines are more difficult. They are designed to loaf at normal speeds. You'll need to find a long uphill stretch of highway, or a powerline road with no jumps or obstacles.

Use a fresh plug, but one with enough miles to have some color showing on the tip.

Begin with tests for the main jet. The engine must run for as close to one minute as you can manage. Run in top gear, wide open for as long as conditions permit. When you must shut off, hit the kill switch, pull in the clutch and coast to a stop. Then pull the plug or plugs. If the tips are brown or gray and the engine ran well, the main jets are right. If they're sooty, go down one size. If they're white, go up one size.

How do you make the change? Again, refer to the manual. It will show the workings of your carb.

Now we get into overlap of the various systems. When the main jets are right, check the needles. You can do a similar plug check for cruising, by finding a nice quiet stretch where you can ease along at part throttle and steady speed, running on the needles as the racing mechanics say. Check the plugs again, with another kill switch shut-down.

Now try opening the throttle at various speeds and loads. A stumble means too lean, a stutter is too rich.

The mechanics for this change may not be in the manual and may take invention. Old carbs and most dirt carbs have a choice of slots. EPA-controlled carbs sometimes don't. Back to the parts counter or street wisdom. Some Honda parts departments can get tiny washers designed to raise needles in current 750 carbs. These are for racing and will be in the Racing Service Center (RSC) catalog. If the dealer has one. We've swapped thick and thin washers in the CVs on Suzuki 450s and raised the needles that way. The Keihins used on XL Hondas have fixed needles except you can remove the holder and shim the needle with whatever tiny washer you have on the workbench. And so it goes, model by model.

The raise and lower can be easily confused though. Raise means raise the needle, lower the needle clip if a clip is used. The important thing to remember is the needle, not the clip is raised to make the mixture richer. Many engines have been ruined because the tuner didn't fully understand what to raise and lower.

When the engine's running right on power, cruise and in-traffic acceleration, there may still be a stutter or stumble just off idle, or the machine might not idle smoothly.

This is the pilot jet at work, or sometimes the idle mixture adjustment. Most carburetors will have both a pilot jet and an idle-mixture screw. If you have an emission-controlled engine, there will probably be no idle-mixture screw sticking out of the carburetor. Instead, a screw will be covered by a small metal plug. If you have access to the screw, you can adjust or make adjustments to improve the idle by turning it in or out. Not all carbs are adjusted the same way, screwing in richening some, and leaning-out others. Better check the manual. This adjustment has nothing to do with running conditions at normal operating speeds. If there's a stumble just off idle, sometimes a different pilot jet can help. This part of the carburetor jetting can't be set from plug readings, so you'll have to experiment, one step at a time, until the problem is solved.

We hope. One system, the whack-throttle enrichment, is not included here. This is tricky. Some carbs, Mikuni, Bing and Amal, have a selection of slides, with different cutaways to induce different degrees of extra richness. CV carbs don't have this. They aren't as sensitive, so the problem doesn't appear often.

If the correct needle position and a wide range of pilot jets won't cure a stumble, you'll have to try another slide. Check your book and use a slide with less cut if it sounds lean, larger cut if rich.

If you have this problem with a carb that's hard to find parts for you can file away at it, raising the leading edge just a bit. Careful here, because the only way to know you've gone far enough is to go too far, i.e. another slide is needed. Wherever possible, juggle jets so you don't get into this system.

NUMBERS

Different makes use different numbering. Some will give the jet size as the number of the drill bit used to make the hole. Others list sizes in total area. Some may be simply parts numbers.

This doesn't matter to you. All you need to know is that higher numbers mean larger holes and more fuel flowing through them. If your Mikuni has a 17.5 pilot jet and your pal's Keihin has a 45 pilot jet, relax. You order the 20 Mikuni and he orders the 48 Keihin.

REPEAT WARNING

Dialing in your carburetion can be great fun. Just as it makes you mad to buy, say, low-restriction air filters only to learn that the engine is too lean at speed, so will you be happy again when the new main jets give back the smoothness and let the filters deliver more mileage and more power.

But don't forget that your carbs didn't read the book. Don't run an engine with the wrong jets any longer than absolutely necessary. Don't make two changes at once, or you won't know which one was wrong and which right. And if you are wrong, go rich. Better soot on the plugs than daylight through your pistons.