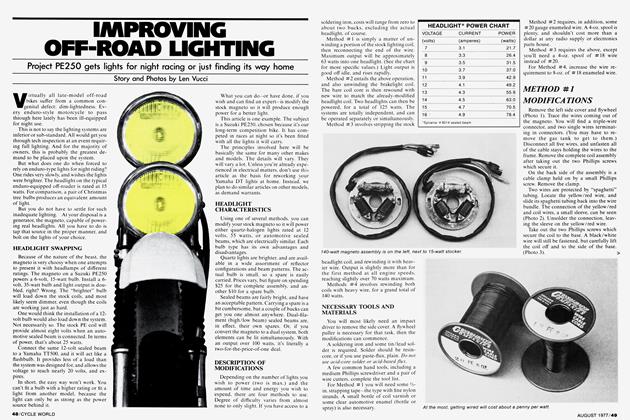

HALOGEN HEADLIGHTS

How to trade your bulb

Ever hear about the clerk at the patent office who quit his job in 1880 or so? He resigned because there were no more inventions to be made.

We laugh. Then we go out and ride through the darkness behind lights perfected and last improved 40 years ago. The technical people back then, like the clerk before them, figured when they came up with reliable bulbs and sealed-beam units they’d done all the human mind could do. So they sat back while the various governing bodies wrote those lights into law. Then they slept for 40 years.

Car lights have never been as good as they could be. Motorcycle lights have been worse. Motorcycle electrics were a joke for years. We’ve put up with switches that fell apart, shorts that came from the factories, coils inadequate for a model airplane glow-plug. Most of all we’ve put up with dim bulbs. We’ve done it because we like our sport and have (until now) been willing to put up with feeble road lights because that’s the way the machine came and the factories and state motor vehicle people know best, don’t they?

Not by half, they don’t.

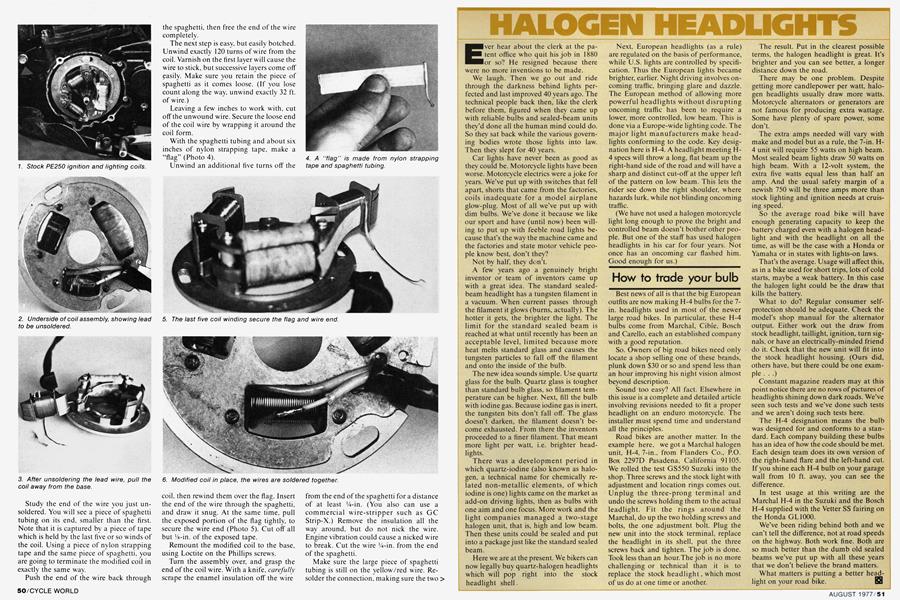

A few years ago a genuinely bright inventor or team of inventors came up with a great idea. The standard sealedbeam headlight has a tungsten filament in a vacuum. When current passes through the filament it glows (burns, actually). The hotter it gets, the brighter the light. The limit for the standard sealed beam is reached at what until recently has been an acceptable level, limited because more heat melts standard glass and causes the tungsten particles to fall off the filament and onto the inside of the bulb.

The new idea sounds simple. Use quartz glass for the bulb. Quartz glass is tougher than standard bulb glass, so filament temperature can be higher. Next, fill the bulb with iodine gas. Because iodine gas is inert, the tungsten bits don’t fall off. The glass doesn’t darken, the filament doesn’t become exhausted. From there the inventors proceeded to a finer filament. That meant more light per watt, i.e. brighter headlights.

There was a development period in which quartz-iodine (also known as halogen, a technical name for chemically related non-metallic elements, of which iodine is one) lights came on the market as add-on driving lights, then as bulbs with one aim and one focus. More work and the light companies managed a two-stage halogen unit, that is, high and low beam. Then these units could be sealed and put into a package just like the standard sealed beam.

Here we are at the present. We bikers can now legally buy quartz-halogen headlights which will pop right into the stock headlight shell.

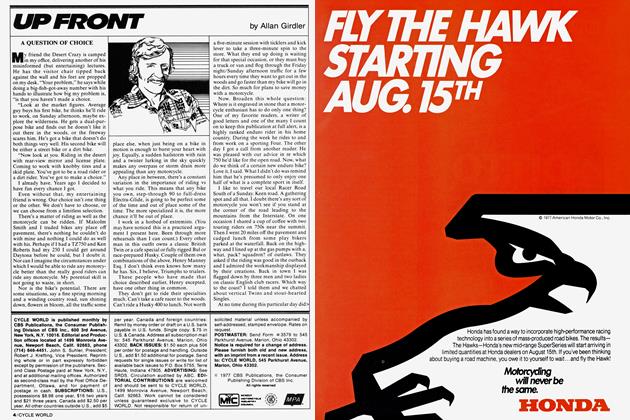

Next, European headlights (as a rule) are regulated on the basis of performance, while U.S. lights are controlled by specification. Thus the European lights became brighter, earlier. Night driving involves oncoming traffic, bringing glare and dazzle. The European method of allowing more powerful headlights without disrupting oncoming traffic has been to require a lower, more controlled, low beam. This is done via a Europe-wide lighting code. The major light manufacturers make headlights conforming to the code. Key designation here is H-4. A headlight meeting H4 specs will throw a long, flat beam up the right-hand side of the road and will have a sharp and distinct cut-off at the upper left of the pattern on low beam. This lets the rider see down the right shoulder, where hazards lurk, while not blinding oncoming traffic.

(We have not used a halogen motorcycle light long enough to prove the bright and controlled beam doesn’t bother other people. But one of the staff has used halogen headlights in his car for four years. Not once has an oncoming car flashed him. Good enough for us.)

news big European outfits are now making H-4 bulbs for the 7in. headlights used in most of the newer large road bikes. In particular, these H-4 bulbs come from Marchai, Cibie, Bosch and Carello, each an established company with a good reputation.

So. Owners of big road bikes need only locate a shop selling one of these brands, plunk down $30 or so and spend less than an hour improving his night vision almost beyond description.

Sound too easy? All fact. Elsewhere in this issue is a complete and detailed article involving revisions needed to fit a proper headlight on an enduro motorcycle. The installer must spend time and understand all the principles.

Road bikes are another matter. In the example here, we got a Marchai halogen unit, H-4, 7-in., from Flanders Co., P.O. Box 2297D Pasadena, California 91105. We rolled the test GS550 Suzuki into the shop. Three screws and the stock light with adjustment and location rings comes out. Unplug the three-prong terminal and undo the screws holding them to the actual leadlight. Fit the rings around the Marchai, do up the two holding screws and bolts, the one adjustment bolt. Plug the new unit into the stock terminal, replace the headlight in its shell, put the three screws back and tighten. The job is done. Took less than an hour. The job is no more challenging or technical than it is to replace the stock headlight, which most of us do at one time or another.

The result. Put in the clearest possible terms, the halogen headlight is great. It’s brighter and you can see better, a longer distance down the road.

There may be one problem. Despite getting more candlepower per watt, halogen headlights usually draw more watts. Motorcycle alternators or generators are not famous for producing extra wattage. Some have plenty of spare power, some don’t.

The extra amps needed will vary with make and model but as a rule, the 7-in. H4 unit will require 55 watts on high beam. Most sealed beam lights draw 50 watts on high beam. With a 12-volt system, the extra five watts equal less than half an amp. And the usual safety margin of a newish 750 will be three amps more than stock lighting and ignition needs at cruising speed.

So the average road bike will have enough generating capacity to keep the battery charged even with a halogen headlight and with the headlight on all the time, as will be the case with a Honda or Yamaha or in states with lights-on laws.

That’s the average. Usage will affect this, as in a bike used for short trips, lots of cold starts, maybe a weak battery. In this case the halogen light could be the draw that kills the battery.

What to do? Regular consumer selfprotection should be adequate. Check the model’s shop manual for the alternator output. Either work out the draw from stock headlight, taillight, ignition, turn signals, or have an electrically-minded friend do it. Check that the new unit will fit into the stock headlight housing. (Ours did, others have, but there could be one example . . .)

Constant magazine readers may at this point notice there are no rows of pictures of headlights shining down dark roads. We’ve seen such tests and we’ve done such tests and we aren’t doing such tests here.

The H-4 designation means the bulb was designed for and conforms to a standard. Each company building these bulbs has an idea of how the code should be met. Each design team does its own version of the right-hand flare and the left-hand cut. If you shine each H-4 bulb on your garage wall from 10 ft. away, you can see the difference.

In test usage at this writing are the Marchai H-4 in the Suzuki and the Bosch H-4 supplied with the Vetter SS fairing on the Honda GL1000.

We’ve been riding behind both and we can’t tell the difference, not at road speeds on the highway. Both work fine. Both are so much better than the dumb old sealed beams we’ve put up with all these years that we don’t believe the brand matters.

What matters is putting a better headlight on your road bike.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue