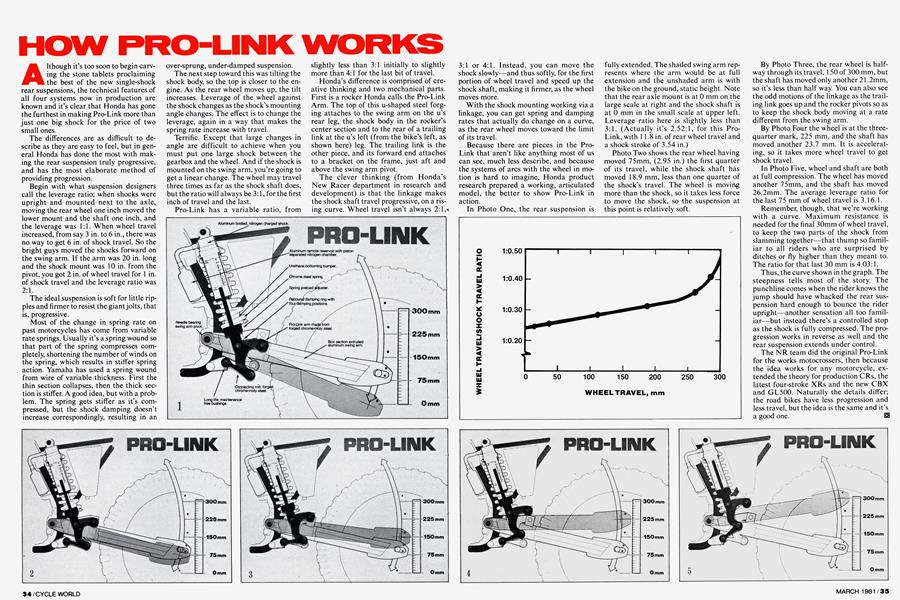

HOW PRO-LINK WORKS

Although it's too soon to begin carving the stone tablets proclaiming the best of the new single-shock rear suspensions, the technical features of all four systems now in production are known and it's clear that Honda has gone the furthest in making Pro-Link more than just one big shock for the price of two small ones.

The differences are as difficult to describe as they are easy to feel, but in general Honda has done the most with making the rear suspension truly progressive, and has the most elaborate method of providing progression.

Begin with what suspension designers call the leverage ratio; when shocks were upright and mounted next to the axle, moving the rear wheel one inch moved the lower mount and the shaft one inch, and the leverage was 1:1. When wheel travel increased, from say 3 in. to 6 in., there was no way to get 6 in. of shock travel. So the bright guys moved the shocks forward on the swing arm. If the arm was 20 in. long and the shock mount was 10 in. from the pivot, you got 2 in. of wheel travel for 1 in. of shock travel and the leverage ratio was 2:1.

The ideal suspension is soft for little ripples and firmer to resist the giant jolts, that is, progressive.

Most of the change in spring rate on past motorcycles has come from variable rate springs. Usually it's a spring wound so that part of the spring compresses completely, shortening the number of winds on the spring, which results in stiffer spring action. Yamaha has used a spring wound from wire of variable thickness. First the thin section collapses, then the thick section is stiffer. A good idea, but with a problem. The spring gets stiffer as it's compressed, but the shock damping doesn't increase correspondingly, resulting in an

over-sprung, under-damped suspension.

The next step toward this was tilting the shock body, so the top is closer to the engine. As the rear wheel moves up, the tilt increases. Leverage of the wheel against the shock changes as the shock's mounting angle changes. The effect is to change the leverage, again in a way that makes the spring rate increase with travel.

Terrific. Except that large changes in angle are difficult to achieve when you must put one large shock between the gearbox and the wheel. And if the shock is mounted on the swing arm, you're going to get a linear change. The wheel may travel three times as far as the shock shaft does, but the ratio will always be 3:1, for the first inch of travel and the last.

Pro-Link has a variable ratio, from slightly less than 3:1 initially to slightly more than 4:1 for the last bit of travel.

Honda's difference is comprised of creative thinking and two mechanical parts. First is a rocker Honda calls the Pro-Link Arm. The top of this u-shaped steel forging attaches to the swing arm on the u's rear leg, the shock body in the rocker's center section and to the rear of a trailing link at the u's left (from the bike's left, as shown here) leg. The trailing link is the other piece, and its forward end attaches to a bracket on the frame, just aft and above the swing arm pivot.

The clever thinking (from Honda's New Racer department in research and development) is that the linkage makes the shock shaft travel progressive, on a rising curve. Wheel travel isn't always 2:1, 3:1 or 4:1. Instead, you can move the shock slowly—and thus softly, for the first portion of wheel travel and speed up the shock shaft, making it firmer, as the wheel moves more.

With the shock mounting working via a linkage, you can get spring and damping rates that actually do change on a curve, as the rear wheel moves toward the limit of its travel.

Because there are pieces in the ProLink that aren't like anything most of us can see, much less describe, and because the systems of arcs with the wheel in motion is hard to imagine, Honda product research prepared a working, articulated model, the better to show Pro-Link in action.

In Photo One, the rear suspension is

fully extended. The shaded swing arm represents where the arm would be at full extension and the unshaded arm is with the bike on the ground, static height. Note that the rear axle mount is at 0 mm on the large scale at right and the shock shaft is at 0 mm in the small scale at upper left. Leverage ratio here is slightly less than 3:1. (Actually it's 2.52:1, for this ProLink, with 11.8 in. of rear wheel travel and a shock stroke of 3.54 in.)

Photo Two shows the rear wheel having moved 75mm, (2.95 in.) the first quarter of its travel, while the shock shaft has moved 18.9 mm, less than one quarter of the shock's travel. The wheel is moving more than the shock, so it takes less force to move the shock, so the suspension at this point is relatively soft.

By Photo Three, the rear wheel is halfway through its travel, 150 of 300 mm, but the shaft has moved only another 21,2mm, so it's less than half way. You can also see the odd motions of the linkage as the trailing link goes up and the rocker pivots so as to keep the shock body moving at a rate different from the swing arm.

By Photo Four the wheel is at the threequarter mark, 225 mm, and the shaft has moved another 23.7 mm. It is accelerating, so it takes more wheel travel to get shock travel.

In Photo Five, wheel and shaft are both at full compression. The wheel has moved another 75mm, and the shaft has moved 26.2mm. The average leverage ratio for the last 75 mm of wheel travel is 3.16.1.

Remember, though, that we're working with a curve. Maximum resistance is needed for the final 30mm of wheel travel, to keep the two parts of the shock from slamming together—that thump so familiar to all riders who are surprised by ditches or fly higher than they meant to. The ratio for that last 30 mm is 4.03:1.

Thus, the curve shown in the graph. The steepness tells most of the story. The punchline comes when the rider knows the jump should have whacked the rear suspension hard enough to bounce the rider upright—another sensation all too familiar—but instead there's a controlled stop as the shock is fully compressed. The progression works in reverse as well and the rear suspension extends under control.

The NR team did the original Pro-Link for the works motocrossers, then because the idea works for any motorcycle, extended the theory for production CRs, the latest four-stroke XRs and the new CBX and GL500. Naturally the details differ; the road bikes have less progression and less travel, but the idea is the same and it's a good one.