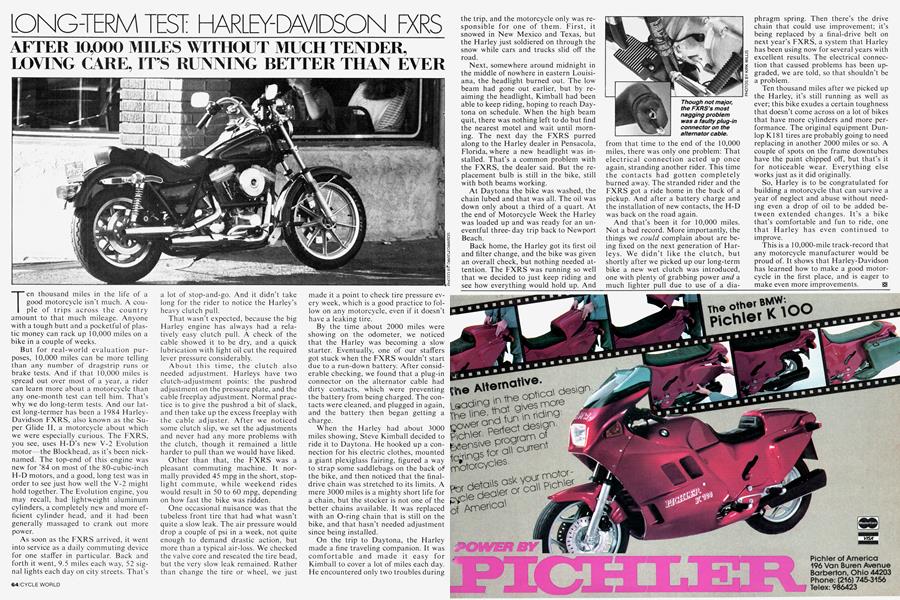

LONG-TERM TEST: HARLEY-DAVIDSON FXRS

AFTER 10,000 MILES WITHOUT MUCH TENDER, LOVING CARE, IT'S RUNNING BETTER THAN EVER

Ten thousand miles in the life of a good motorcycle isn’t much. A couple of trips across the country amount to that much mileage. Anyone with a tough butt and a pocketful of plastic money can rack up 10,000 miles on a bike in a couple of weeks.

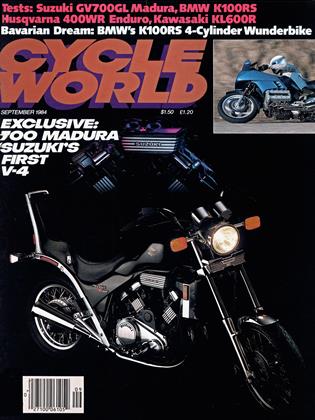

But for real-world evaluation purposes, 10,000 miles can be more telling than any number of dragstrip runs or brake tests. And if that 10,000 miles is spread out over most of a year, a rider can learn more about a motorcycle than any one-month test can tell him. That’s why we do long-term tests. And our latest long-termer has been a 1984 HarleyDavidson FXRS, also known as the Super Glide II, a motorcycle about which we were especially curious. The FXRS, you see, uses H-D's new V-2 Evolution motor—the Blockhead, as it’s been nicknamed. The top-end of this engine was new for ’84 on most of the 80-cubic-inch H-D motors, and a good, long test was in order to see just how well the V-2 might hold together. The Evolution engine, you may recall, had lightweight aluminum cylinders, a completely new and more efficient cylinder head, and it had been generally massaged to crank out more power.

As soon as the FXRS arrived, it went into service as a daily commuting device for one staffer in particular. Back and forth it went, 9.5 miles each way, 52 signal lights each day on city streets. That’s a lot of stop-and-go. And it didn’t take long for the rider to notice the Harley’s heavy clutch pull.

That wasn’t expected, because the big Harley engine has always had a relatively easy clutch pull. A check of the cable showed it to be dry, and a quick lubrication with light oil cut the required lever pressure considerably.

About this time, the clutch also needed adjustment. Harleys have two clutch-adjustment points: the pushrod adjustment on the pressure plate, and the cable freeplay adjustment. Normal practice is to give the pushrod a bit of slack, and then take up the excess freeplay with the cable adjuster. After we noticed some clutch slip, we set the adjustments and never had any more problems with the clutch, though it remained a little harder to pull than we would have liked.

Other than that, the FXRS was a pleasant commuting machine. It normally provided 45 mpg in the short, stoplight commute, while weekend rides would result in 50 to 60 mpg, depending on how fast the bike was ridden.

One occasional nuisance was that the tubeless front tire that had what wasn't quite a slow leak. The air pressure would drop a couple of psi in a week, not quite enough to demand drastic action, but more than a typical air-loss. We checked the valve core and reseated the tire bead, but the very slow leak remained. Rather than change the tire or wheel, we just made it a point to check tire pressure every week, which is a good practice to follow on any motorcycle, even if it doesn’t have a leaking tire.

By the time about 2000 miles were showing on the odometer, we noticed that the Harley was becoming a slow starter. Eventually, one of our staffers got stuck when the FXRS wouldn't start due to a run-down battery. After considerable checking, we found that a plug-in connector on the alternator cable had dirty contacts, which were preventing the battery from being charged. The contacts were cleaned, and plugged in again, and the battery then began getting a charge.

When the Harley had about 3000 miles showing, Steve Kimball decided to ride it to Daytona. He hooked up a connection for his electric clothes, mounted a giant plexiglass fairing, figured a way to strap some saddlebags on the back of the bike, and then noticed that the finaldrive chain was stretched to its limits. A mere 3000 miles is a mighty short life for a chain, but the stocker is not one of the better chains available. It was replaced with an O-ring chain that is still on the bike, and that hasn’t needed adjustment since being installed.

On the trip to Daytona, the Harley made a fine traveling companion. It was comfortable and made it easy for Kimball to cover a lot of miles each day. He encountered only two troubles during the trip, and the motorcycle only was responsible for one of them. First, it snowed in New Mexico and Texas, but the Harley just soldiered on through the snow while cars and trucks slid off the road.

Next, somewhere around midnight in the middle of nowhere in eastern Louisiana, the headlight burned out. The low beam had gone out earlier, but by reaiming the headlight, Kimball had been able to keep riding, hoping to reach Daytona on schedule. When the high beam quit, there was nothing left to do but find the nearest motel and wait until morning. The next day the FXRS purred along to the Harley dealer in Pensacola, Florida, where a new headlight was installed. That’s a common problem with the FXRS, the dealer said. But the replacement bulb is still in the bike, still with both beams working.

At Daytona the bike was washed, the chain lubed and that was all. The oil was down only about a third of a quart. At the end of Motorcycle Week the Harley was loaded up and was ready for an uneventful three-day trip back to Newport Beach.

Back home, the Harley got its first oil and filter change, and the bike was given an overall check, but nothing needed attention. The FXRS was running so well that we decided to just keep riding and see how everything would hold up. And from that time to the end of the 10,000 miles, there was only one problem: That electrical connection acted up once again, stranding another rider. This time the contacts had gotten completely burned away. The stranded rider and the FXRS got a ride home in the back of a pickup. And after a battery charge and the installation of new contacts, the H-D was back on the road again.

And that’s been it for 10,000 miles. Not a bad record. More importantly, the things we could complain about are being fixed on the next generation of Harleys. We didn’t like the clutch, but shortly after we picked up our long-term bike a new wet clutch was introduced, one with plenty of grabbing power and a much lighter pull due to use of a diaphragm spring. Then there’s the drive chain that could use improvement; it’s being replaced by a final-drive belt on next year’s FXRS, a system that Harley has been using now for several years with excellent results. The electrical connection that caused problems has been upgraded, we are told, so that shouldn’t be a problem.

Ten thousand miles after we picked up the Harley, it’s still running as well as ever; this bike exudes a certain toughness that doesn’t come across on a lot of bikes that have more cylinders and more performance. The original equipment Dunlop K181 tires are probably going to need replacing in another 2000 miles or so. A couple of spots on the frame downtubes have the paint chipped off, but that’s it for noticeable wear. Everything else works just as it did originally.

So, Harley is to be congratulated for building a motorcycle that can survive a year of neglect and abuse without needing even a drop of oil to be added between extended changes. It’s a bike that’s comfortable and fun to ride, one that Harley has even continued to improve.

This is a 10,000-mile track-record that any motorcycle manufacturer would be proud of. It shows that Harley-Davidson has learned how to make a good motorcycle in the first place, and is eager to make even more improvements. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue