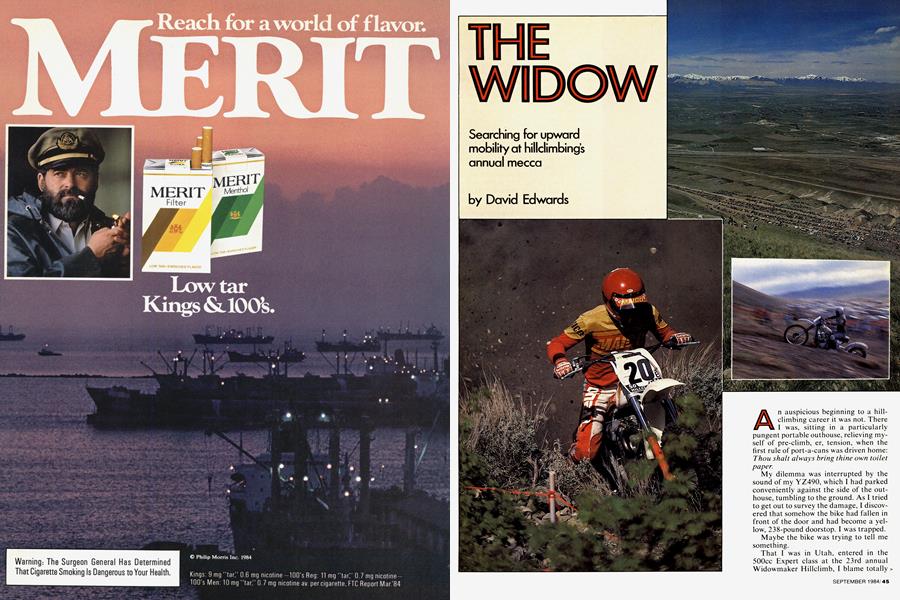

THE WIDOW

Searching for upward mobility at hillclimbing's annual mecca

David Edwards

An auspicious beginning to a hillclimbing career it was not. There I was, sitting in a particularly pungent portable outhouse, relieving my-self of pre-climb, er, tension, when the first rule of port-a-cans was driven home: Thou shalt always bring thine own toilet paper.

My dilemma was interrupted by the sound of my YZ490, which I had parked conveniently against the side of the outhouse, tumbling to the ground. As I tried to get out to survey the damage, I discovered that somehow the bike had fallen in front of the door and had become a yellow, 238-pound doorstop. I was trapped.

Maybe the bike was trying to tell me something.

That I was in Utah, entered in the 500cc Expert class at the 23rd annual Widowmaker Hillclimb, I blame totally > on a friend of mine. He’s the technical editor of a dirt-bike magazine and a devout Mormon. Give him a chance to ride motorcycles and get within earshot of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and he’s happier than a cat on a dairy farm.

We'd talked about entering the Widowmaker before, but then we'd also talked about touring around the world on dual-purpose bikes and entering 24-hour endurance roadraces on modified motocrossers; so I was still a little surprised when he called to say he’d entered us in the hillclimb. And by the way, he said, it’s this weekend.

Armed with cashews, bagels, orange juice and Elton John tapes, we set off on the 14-hour trek from California through Nevada to Utah. Along the way, my friend entertained me by picking out only the world's worst hamburger joints to stop at, giving a running account of various Mormon landmarks and pointing to sheer cliffs and saying, “The Widowmaker’s about that steep . . . ’course it’s a lot rougher than that.” At least it was better than hearing Elton John sing Crocodile Rock one more time.

If my friend was exaggerating to psyche me out, he didn't need to. I was already terrified of climbing hills. My formative dirt-riding years were spent in north Texas, a region not noted for its mountainous terrain. The hilliest thing in the region is probably a Sunday-afternoon lineup of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, and there are state laws against riding on them, anyway.

Competitors aren’t allowed practice runs at Widowmaker, nor can they walk the hill before their attempts; so to help quell my fears, the day before the climb we decided to practice at a hilly riding area a few miles away. The practice session revealed three things. First, even though the Yamaha was jetted too rich for Utah’s altitude, it felt like it could climb Mt. Everest when it came on the main jet. Second, despite the bike’s incredible power, it was obvious that I would probably not be going back to California with a Widowmaker plaque tucked under my arm. Third, and best of all, hillclimbing is a lot more frightening to look at and think about than it is to do. The end of an attempt usually means coming to a gradual stop, turning into the hill, dismounting and then bulldogging the bike back down. Not much drama at all, really.

Still, I couldn't stop thinking that when it came time for my attempts at the Widowmaker, I'd flip the bike over backwards, come tumbling spectacularly back to the base of the hill, have the bike land on top of me and be credited with a climb of three feet.

I guess I can get some consolation from the knowledge that hillclimbs have been terrifying riders like me for almost 70 years. Although eclipsed today by motocross, roadracing and flat track, hillclimbing once was the most popular form of motorcycle competition in America. Just after World War I and into the Twenties, hillclimbs dotted the country from New York to California. Competition between the three major American manufacturers of the period, Harley-Davidson, Indian and Excelsior, was intense, and a win at a major hillclimb was hawked proudly in a company’s newspaper and magazine ads.

Then came the Depression and World War II, which effectively put an end to hillclimbing for more than a decade. The sport has remained in the backwaters of the U.S. motorcycling scene ever since, although hillclimb enthusiasts will tell you that the sport is on the way back to its former glory. Still, there’s no danger of hillclimbing being billed as America’s fastest-growing form of motorcycle competition.

Today, hillclimbing is split into two factions. There are the Eastern-state climbs, sanctioned by the American Motorcyclist Association and usually run on hills of between 300 and 400 feet in length. The Western-state riders, however, don’t care much for the AMA, one of the reasons being that while the organization’s rules permit chains to be wrapped around rear wheels for traction, they forbid paddles. Chains are fine, the Western guys say, for a 350-foot, timedrun hill in upstate New York; but when you’re sitting at the base of a 1000-footplus monster in Utah, Oregon or Montana, you need all the earth-gripping advantage you can get.

East or West, the sport’s most prestigious event is the Widowmaker Hillclimb—The Widow, for short. Situated just outside Salt Lake City, the Widowmaker is dwarfed by many of the snow-capped peaks in the nearby Wasatch Mountains, but as a hill it’s one hell of an overachiever.

If all you know about Widowmaker comes from the movie On Any Sunday and the scene where the ever-smiling Malcolm Smith forgets to turn his gas on before climbing, then you’re behind the times. That 650-foot hill doesn’t even qualify as a good practice hill anymore. Even four-wheel-drive trucks have gone over that hill. The new hill is along the same ridge as the old one, but it’s almost 1000 feet longer and a lot more difficult.

In fact, just describing the steepness of the Widowmaker is difficult in itself. To say that it’s an 80-percent grade—that for every 100 feet you go forward, you go upward 80 feet—doesn’t convey the steepness. Photographs don’t do it justice. Standing at the bottom of the hill during the riders’ meeting, I got a weird visual image that may help: Imagine the angle that the deck of the oceanliner Titanic took during the ship’s deathplunge to the bottom of the Atlantic. Now cover the deck with loose dirt, shale, rocks, boulders and sagebrush. An odd simile? Well, standing at the base of the Widowmaker and looking up, way up, makes for strange thoughts.

The other would-be hilltoppers at the riders’ meeting were doing a lot of looking up as well. As you might guess, hillclimbers are slightly different from your average motocrosser or roadracer. If hillclimbing were a tavern, you'd say it had ambience. Age doesn’t seem to matter; the youngest rider was 8, the oldest in his seventies. Neither are hillclimbers slaves to motofashion. Although many of the competitors wear motocross gear, most show up in jeans, work boots and flannel shirts. A visorless K-Mart helmet tops the ensemble. Sunglasses and cigars are optional.

No less iconoclastic are the machines these people ride. Walking through the pits is enough to renew your faith in good old American ingenuity. The Japanese might make better cameras, the Germans better autobahns, the French better wine, the English better Indy-winning racecars, but, by God, let somebody try to bolt together a better hillclimber. Many of these creations seemed to be inspired by the “What If” theory of building, as in, “What if we put that Jawa speedway engine in my CZ frame?” or “What if we stuff that Z-1 motor in a KX250 frame?” or “What if we take a Yamaha 1100 engine, add a parallelogram swingarm and then chrome everything in sight?”

All of these contrivances, and more, were in attendance at the Widowmaker. And the event’s organizers, the Salt Lake City Bees, divided this assortment of machinery into seven classes. The two Sportsman classes were open only to Utah riders, so out-of-state amateur riders, even beginners like me and my friend the tech editor, had to ride with the Experts. The professionals had two classes, (U700cc Exhibition and Open Exhibition, with $20,000 in prize money and the chance to win $1000 by being the first over the hill, plus another $1000 for winning the end-of-the-day shootout between all former Widowmaker winners.

If an Exhibition rider were to win everything he entered and were first over the hill, he could take home $6500.

Diversity and ingenuity aside, the most popular way of attacking the hill for the amateurs seemed to be on a recent-model Japanese motocrosser. The winning solution was fairly easy: Bolt on a six-inch swingarm extension, hop-up the engine, shave every other knob off the rear tire for added traction, look up and keep the throttle pegged. Yamahas won every Expert and Sportsman class except Open Expert, which was taken by a Triumph.

The stars of the show, however, were the super-extended Exhibition class bikes, in particular the Open machines. The favorite in that class, as he’s been for years, was Californian Kerry Peterson on his nitromethane-fueled, 1500cc Harley-Davidson. Peterson, 28, has been climbing hills since 1972 when he finished second in his first attempt at Saddleback Park’s Matterhorn Hillclimb. He progressed up the hillclimb ladder, mostly using a Maico frame fitted with first a piston-breaking Yamaha SC500 two-stroke, then an exScott Autrey Jawa speedway engine. In 1981 he hooked up with a Harley-Davidson and Maico dealer who supplied Peterson with bikes and parts the hillclimb equivalent of factory sponsorship. Since then, Peterson has won every major non-AMA hillclimb, including Canada’s hillclimb championship.

Maico’s financial troubles prompted Peterson to switch to Honda sponsorship this year, although he still uses the Harley in the Open class, a situation Honda isn’t very happy about and that could change if Peterson and his mechanic, John Bjorkman, can latch onto an RS750 dirt-track motor and increase displacement enough to be competitive with the Harleys.

After 12 years of climbing, Peterson still has the desire to beat the hill. “It’s one heck of a challenge,” says Peterson when asked why. “Not only do you beat your rivals, but you beat the mountain . . . you feel like you've conquered it.”

At this year's Widowmaker, Peterson had more to worry about than just the mountain. Steve Stith, riding a Maico in the 700 class and a Harley almost 200cc bigger than Peterson’s in the Open class, was out to break his perennial secondplace-guy image. Keith Roessler, on a screaming, 1 125cc Honda Four, was retiring after the climb and wanted to go out a winner. Jim True had most of the bugs exorcised from his YZ980 two YZ490 motocross top-ends grafted onto handmade cases and mated to a Honda 750 transmission a bike that looked and sounded like the Devil’s very own roto-tiller. Then there was Vince Bertolucci, probably the most determined rider on the hill. Bertolucci lost a leg in a non-motorcycle accident, and before each run his pit crew bungee-cords the artificial leg to his Triumph's footpeg.

Peterson was the 27th Open Exhibition rider to try the hill. He lined up the bike at the base of the hill, in front of a sheet of plywood intended to keep the rear tire's roost from wiping out scores of spectators and hill workers. Peterson launched out of the hole and up the hill, the buzzsaw of a rear wheel spewing out a cloud of dust peppered with fast-moving rocks. He powered through the middle portion of the climb with no problems, rolling on and off the throttle to gain momentum while controlling wheelspin. Then, at about 900 feet, just as he was negotiating a shallow curve to the left in extremely soft dirt, Peterson bobbled. The run seemed to stop for a moment, as if both Peterson and the bike had paused for a breath. Then they continued, setting sights on a four-foot-high ledge at the 1 100-foot mark. The few other climbers who had gotten to that point had flung themselves up the ledge and stopped right where they had landed. Not Peterson. He motored up to the ledge and rolled off the throttle, counting on momentum to carry him over the ledge and knowing that his bike had enough power in reserve to get him going again.

That strategy worked. Peterson rolled, almost casually, over the ledge, then the scoops of the paddles sank into the ground and threw out a grenade’s worth of dirt. Peterson was on his way to the top, and to becoming the only rider to see the crest of the hill all day. Fifteen thousand spectators at the bottom of the hill started cheering, waving flags and honking their car horns. It had taken almost 38 seconds to cover the 1600 feet, on a bike that has enough power to do a level quarter-mile dragstrip run ( 1 320 feet) in under 10 seconds.

In the 700 class, Peterson didn't fare as well. Hampered by an early start number a disadvantage because the later the start position, the more worn-in and easier to ride the hill becomesPeterson didn't crack the Top 10. And in the shootout, a broken fuel-injector line put an end to his run just as he crested the ledge. Steve Stith, something of a Peterson piotégé, took the wins in both classes.

And what of my attempts? Was I rescued from the indignity of a results-list that had me in last place? Did I avoid having an asterisk next to my name, with a "Did not start, trapped in outhouse" explanation attached?

Thankfully, yes. I made it to the start line just in time and scampered a rather impotent 200 feet up the hill before gravity, aided by lack of skill, had its way. My second run was lower still. A long way from the 869-foot run turned in by the winner, 14-year-old Travis Whitlock, bui not the worst footage of the 71 class entrants, either. My friend the tech editor climbed almost 300 feet to wrap up the unofficial Best Climb by a Journalist title.

I’ve already decided that I'm going back next year. I need to find some hills and practice a lot, but at least my terror of hillclimbing is gone. In fact, my fear of getting hurt was way out of proportion with the risk involved. As far as I saw, the Widowmaker’s most serious injury was nothing more than a sprained ankle. Of course, Sprained Ankle Maker doesn’t have the same romantic ring to it.

I’m going back with the proper machinery as well; no more stock-swingarm motocrossers. I've already got a few candidates for the chassis; now, does anyone know where I can get a good TZ750 roadrace engine? 03

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

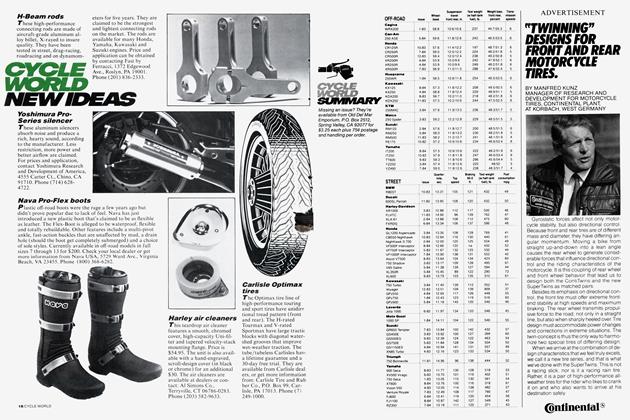

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

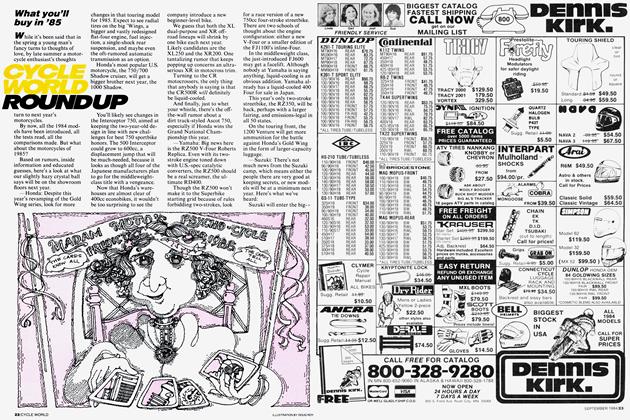

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Features

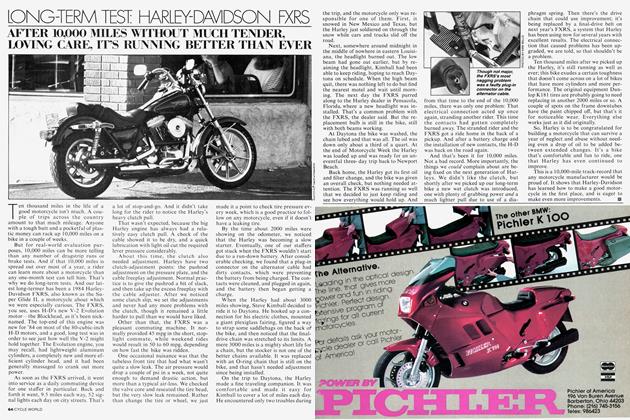

FeaturesLong-Term Test: Harley-Davidson Fxrs

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Departments

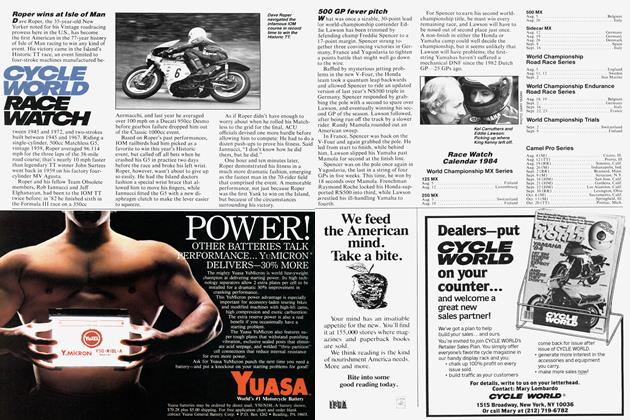

DepartmentsCycle World Race Watch

SEPTEMBER 1984