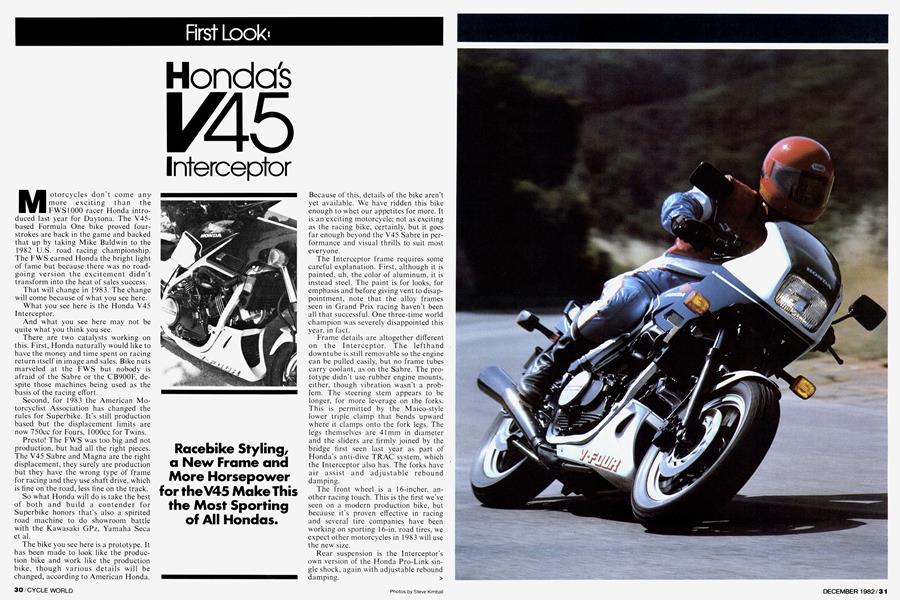

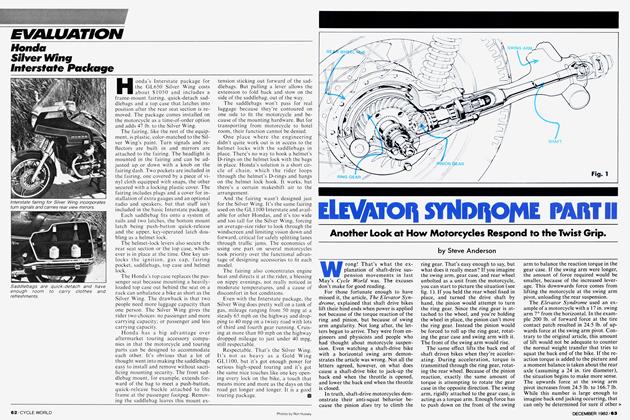

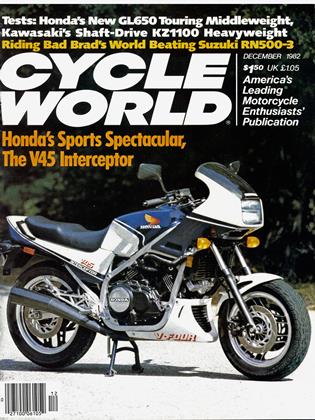

First Look: Honda's V45 Interceptor

Racebike Styling, a New Frame and More Horsepower for theV45 Make This the Most Sporting of All Hondas.

Motorcycles don't come any more exciting than the FWS 1000 racer Honda introduced last year for Daytona. The V45based Formula One bike proved fourstrokes are back in the game and backed that up by taking Mike Baldwin to the 1982 U.S. road racing championship. The FWS earned Honda the bright light of fame but because there was no roadgoing version the excitement didn’t transform into the heat of sales success.

That will change in 1983. The change will come because of what you see here.

What you see here is the Honda V45 Interceptor.

And what you see here may not be quite what you think you see.

There are two catalysts working on this. First, Honda naturally would like to have the money and time spent on racing return itself in image and sales. Bike nuts marveled at the FWS but nobody is afraid of the Sabre or the CB900F, despite those machines being used as the basis of the racing effort.

Second, for 1983 the American Motorcyclist Association has changed the rules for Superbike. It’s still production based but the displacement limits are now 750cc for Fours, lOOOcc for Twins.

Presto! The FWS was too big and not production, but had all the right pieces. The V45 Sabre and Magna are the right displacement, they surely are production but they have the wrong type of frame for racing and they use shaft drive, which is fine on the road, less fine on the track.

So what Honda will do is take the best of both and build a contender for Superbike honors that’s also a spirited road machine to do showroom battle with the Kawasaki GPz, Yamaha Seca et al. The bike you see here is a prototype. It has been made to look like the production bike and work like the production bike, though various details will be changed, according to American Honda.

Because of this, details of the bike aren't yet available. We have ridden this bike enough to whet our appetites for more. It is an exciting motorcycle; not as exciting as the racing bike, certainly, but it goes far enough beyond the V45 Sabre in performance and visual thrills to suit most everyone.

The Interceptor frame requires some careful explanation. First, although it is painted, uh, the color of aluminum, it is instead steel. The paint is for looks, for emphasis and before giving vent to disappointment, note that the alloy frames seen in Grand Prix racing haven’t been all that successful. One three-time world champion was severely disappointed this year, in fact.

Frame details are altogether different on the Interceptor. The lefthand downtube is still removable so the engine can be pulled easily, but no frame tubes carry coolant, as on the Sabre. The prototype didn't use rubber engine mounts, either, though vibration wasn’t a problem. The steering stem appears to be longer, for more leverage on the forks. This is permitted by the Maico-style lower triple clamp that bends upward where it clamps onto the fork legs. The legs themselves are 41mm in diameter and the sliders are firmly joined by the bridge first seen last year as part of Honda’s anti-dive TRAC system, which the Interceptor also has. The forks have air assist and adjustable rebound damping.

The front wheel is a 16-incher, another racing touch. This is the first we’ve seen on a modern production bike, but because it’s proven effective in racing and several tire companies have been working on sporting 16-in. road tires, we expect other motorcycles in 1983 will use the new size.

Rear suspension is the Interceptor’s own version of the Honda Pro-Link single shock, again with adjustable rebound damping. >

Also part of the racing heritage is a small frame-mount fairing. The instruments are mounted in a fairing panel rather than on the top triple clamp, so steering mass is reduced. And everything possible, for example the exhaust system, footpegs, stands and engine parts, is tucked in for maximum cornering clearance.

At the heart of the Interceptor is a VFour 748-cc engine that shares many parts with the V45 Sabre and Magna.

But there are major differences. First seen is the angle of the cylinders. They’re still mounted 90° apart but the vee has been tilted backwards: like the FWS engine, the Interceptor has its rear cylinders about 45° from vertical leaning back, the front pair is nearly 45° from vertical but tipped forward. The Sabre and Magna vees have the rear almost vertical, the front almost horizontal.

Why? Because with the rear cylinders lower, the tank can be lower. With the front cylinders more upright, the wheelbase can be shorter; the Interceptor’s wheelbase is nearly 2 in. less than the Sabre’s. And engine weight, the major factor in the bike’s mass, is more toward the center of the machine as well as lower.

There are secondary benefits as well. With the forward-tilt Sabre and Magna, there’s room for the radiator above the front cylinder head, so that’s where it goes and it’s so easy to see that the engine gets lost.

The Interceptor has two radiators. One is nicely out of the way just below the steering head. The other is housed below the front cylinders, tucked inside a scoop that looks like a GP fairing. The radiator looks like an oil cooler, which doesn’t hurt the race-derived impression either.

The driveline’s major difference is chain drive. The engineering for this was done in conjunction with the new angle for the vee; the Interceptor has a different crankcase. There’s a minimum of parts inside, with the engine spinning the wet clutch through straight-cut primary gears, the clutch on the end of the gearbox mainshaft and the drive sprocket mounted on the countershaft. No jackshafts or auxiliary shafts are needed on this engine, which remains narrow and low even with parts on the end of the short and stiff crankshaft.

Honda engineering likes the practical approach. When they did the shaft drive V45s, the best way to get the pinion gears in the right place and the engine as short as possible was to have the engine contra-rotating, that is, spinning in the opposite direction to the bike’s wheels.

For the Interceptor, the same desire for a compact drivetrain has led them to spin the engine the other way, in the same direction as the wheels.

So. In one sense, this engine is the same as the earlier versions. It’s a dohc V-Four with cylinder banks at 90°, a plain bearing crankshaft with two throws in the same plane. The cylinders aren’t removable but have cast-in liners. This is the same approach used on the CX500 V-Twin and Honda has found that it works. Nor was it a handicap for this engine; because they had to change the gearbox, it was no more trouble to cast the cylinders at a different angle to the crank.

The four camshafts operate the four valves per cylinder by way of lever-type followers. The engine is distinctive by its extreme oversquare configuration, 70mm bore and 48.6mm stroke. It has a relatively high 10.5:1 compression ratio, which manages to work well enough with regular gasoline because the compact combustion chamber and relatively flat head makes for a quick burning engine. This is something of a buzz word these days, being used on some of the more powerful car and bike engines. On the V45 Hondas it works beautifully. And it is a compact powerplant and it fits into a motorcycle nicely.

Most of the power-making parts are shared with the other V45 models, i.e. the heads, cylinders, and valve gear are the same. All the V45 Hondas get detail changes to cam timing and carburetion that will improve horsepower for 1983. Beyond this, Honda says the Interceptor will make more power than the Sabre or Magna. Carburetors are a combination of downdraft and sidedraft, as on the laydown engine of the Sabre and Magna. To supply those carbs with air, there’s an airbox and intake under the front of the gas tank, instead of the air filters and black boxes sticking out of the sides of the Sabre. The exhaust tucks tightly under the Interceptor’s engine and finally branches out into a pair of black painted mufflers, also tucked tightly into the sides of the motorcycle.

Honda claims 84 bhp at the crank-> shaft, up from the 80 bhp of the Sabre and Magna. Honda spokesmen had no information on other engine changes. If our brief hour of riding the prototype is any indication, the Interceptor has an engine very much like the Sabre. It makes power down low and it makes more power up high. It’s a smooth engine, but the solidly mounted engine transmits some vibration to the frame and rider, though much less than on the CB750, for instance. Of course the production bike could be different from our photo bike but the overall power output felt about the same as a Kawasaki GPz750.

How much the bike weighs will have a large bearing on performance. Honda claims 484 lb. dry, which will probably translate into a little over 500 lb. when carrying a half tank of gas, again about even with the GPz750 Kawasaki. That should make for better acceleration than the heavier and less powerful Sabre, a 525 lb. motorcycle that ran through the quarter mile in 12.16 sec. at 108.43 sec. In Honda’s prototype testing, the Interceptor has been about a third of a second quicker through the quarter mile than the Sabre.

Gearing could also influence performance of the Interceptor. On the original V45 Hondas, a shaft was used and the transmissions had six speeds, with very tall overall gearing in top gear. The Interceptor has five speeds, though American Honda, again, didn't have information on the ratios. First gear felt comparable to 1st on the Sabre, while top gear wasn’t as overgeared. It could have the same ratios as the bottom five ratios of the Sabre or Magna, which wouldn't be all that bad. That would make for a calculated 5th gear top speed of about 130 mph, and the Interceptor might have the power to pull that.

Wheelbase can also affect performance. Honda claims a wheelbase of 58.6 in. on the Interceptor, about 2 in. shorter than the wheelbase of the Sabre. That should contribute to quicker handling, as should the 16 in. front tire. In our brief ride, which was spent riding up and down narrow mountain roads for photos, the Interceptor displayed marvelous handling characteristics. It was noticeably easier to change directions back and forth on the Interceptor than on the Sabre. Even with the short, CBXstyle adjustable handlebars, steering effort was light and flicking the bike back and forth at low speeds through the tight corners was enjoyable and confidence inspiring. At more extreme angles of lean the Interceptor begins to resist steering effort more, apparently from the large tires and their relatively flat profiles. This gives the Interceptor a self-limiting tendency before a rider really heaves on the handlebars and forces the machine to scrape pegs on the pavement. Before it does that, the angle of lean is well beyond that of current Honda sport bikes and near the limits of any street tire.

Braking power and control was excellent, but then so was the braking performance of the Sabre. The double front discs and single rear disc have enormous power, and the wide front tire uses lots of that braking power. Honda’s double piston calipers have wonderful feel, with little of the sponginess of other brakes. The single fork leg anti-dive system does an unobtrusive job of keeping front end dive under control.

Form and function come together when a rider sits on the Interceptor. It certainly looks sporting, even a little extreme. It isn't uncomfortable, though. While the handlebars appear to have little rise, the steering head is unnaturally high, making for a relatively normal riding posture, with enough room for any rider.

How much the fairing does to protect the rider, is questionable. It has a small frontal area and sleek shape. It has a greater effect on the appearance of the motorcycle, though a rider can tuck behind part of the fairing windshield. The riding posture wouldn’t be uncomfortable for a ride of several hundred miles, particularly at speed, where the lower crouch gets the rider out of the wind.

Sitting on the bike, you realize how many of the details have been changed from the Sabre and Magna and every other Honda in production. This gas tank could only fit on a frame like the Interceptor’s. And on the left side of the tank is a rotating knob, like the choke knob on a Suzuki Katana, but on the Interceptor it’s the petcock. It’s handy, easy to operate and looks good. Even the mirrors are unusual, bending outwards so they can clear the windshield.

The instruments, housed in a brushed metal panel, are easy to read, and now that the 85 mph law has been changed, there’s a 140 mph speedometer included, with the 10,500 rpm redline tach, the fuel gauge and the temperature gauge. Compared with the video display of the Sabre, this is an attractive, simple, business-like instrument display for the business of riding a motorcycle well. All the 1983 Hondas will have speedometers that reflect the top speeds of the motorcycles, according to Honda spokesmen.

The paint was something of a surprise, blue not being Honda’s racing color. There will be a choice of blue or red, we were told, but the red will be a deep candy, again not the Honda red-whiteblue seen on the GP bikes and the endurance racers.

This is no accident. The Interceptor w ill serve as Honda’s Superbike weapon for the coming season. There will be a factory team, a support team and a program for privateers. Honda wants to establish the Interceptor as the performance bike so the paint was picked not to look like the other racing machines.

The production, road-going version is designed to meet limits imposed by Honda. There’s obviously potential in the engine that will be unleashed only for racing. The Interceptor doesn’t set records for low weight or maximum power.

But with its roadracer styling, eyecatching frame and bent-Sabre engine, the Interceptor is Honda’s most sporting motorcycle and at first impression, it’s hard to fault. The handling is a treat, the power more than adequate and the appearance, the Interceptor’s primary thrust, spells out its job:

To boldly go where only racebikes have gone before. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue