DUCATI 500 GTL

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Different Twin in A Different Package

• First things first. What we have on dis play here is a Ducati 500GTL, a 500cc Twin. a rare and new and-most of allItalian motorcycle. This machine is not like mass-produced motorcycles. Figures and comparisons in the normal vein have no meaning here, so any reader tempted to consider this as simply another 500cc Twin is advised at the outset not to continue.

Okay? Fine. Now that present company is limited to those of us with an appreciation for things of the spirit, we'll begin again.

With a legend. Ducati motorcycles began in 1950. when the post-war shortage of transportation persuaded Ducati to enter the motorbike field. Company stock was held by the Italian government and the Vatican, so raising capital was no problem. Peppy scooters became best sellers and were replaced by sporting small motorcycles, leading the company into road racing, larger engines and several world championships. In the U.S. the make w'as famous for the Diana, one of the few sporting road bikes which could actually won production road races; for the 350 Single; for desmodromic valve actuation; and for the 750 and 900cc Twins which still win superbike and endurance races.

Ducati. then, has credentials. This is stressed because the 500 Twin is a new' model, in the U.S. and at home, and it is a different machine indeed.

Especially the engine. It's a vertical Twin of striking appearance. There are rather large engine and transmission cases, highly polished and shaped like a teardrop going the w'rong way. Atop the cases sits a square black cylinder barrel. Above that is sort of a triangular box, inside which is a single camshaft working rocker arms to inclined valves, two per cylinder. The combustion chambers are classically hemispherical. The cylinders are canted 10 degrees forward from vertical and at 78mm bore by 52mm stroke, the Ducati 500 Twin is severely oversquare, the normal racing method of allowing large valves and high engine speeds, i.e. lots of power for a given displacement.

Most unusual of all is the crankshaft. Most four-stroke vertical Twins use a one-plane crank, wdth the pistons rising and falling together wáth the firing sequences staggered. Firing impulses are evenly spaced, although large counterweights are required for an acceptable level of vibration.

Ducati’s 500 Twin has a 180-degree crank, with one piston at top dead center when the other is at bottom dead center.

Primary balance is markedly improved. The firing order isn't. The singlethrow crank Twin works as if it was two Singles joined at mid-cycle. The flat crank Twin works as if it was one side of an inline Four: two power pulses, two blank spaces, two power pulses. tw;o blank spaces. So while initial balance may be better and the counterweights can be lighter and smaller, the flat crank Twin always sounds and feels rough.

The 500 is fitted with two 30mm Dellorto carburetors and there’s a separate exhaust pipe and muffler for each cylinder. The camshaft has 280 degree duration, on the radical side of a highperformance street grind, and compression ratio is 9.6:1. also normal but which could allow' use of low-lead fuel in extreme need. Aside from the crank design, the Ducati 500 is conventional in configuration and detail. Rare for an Italian engine is the appearance: Seldom does one see an engine so obviously three basic shapes bolted together.

American Ducati experts say this engine has been in the works for several years but has only recently gone into production. If so, Ducati planned well. Gearshift is on the left and foot brake lever on the right and there is no sign of any conversion having been made.

The frame is a bit less conventional, as the single front downtube bolts to the front of the engine case and the rear of the case bolts to widely spaced flanges at the rear downtubes. The engine thus serves as part of the frame. The bulk of the drivetrain becomes a stiffener for the frame, always a good thing, and because there is no bottom tube or tubes below the engine, the engine can be closer to the ground with good ground clearance. The engine/frame system is clearly designed for handling and a lower center of gravity, that is. high-speed performance.

Front forks and rear shocks/springs are by Marzocchi. with no visible distinctions. The front disc and rear drum brakes are sized in keeping with the bike’s weight.

The specifications, in short, are standard 500cc sporting roadster. There are also signs of that mix of careful planning and apparent oversight which characterizes the modern specialist motorcycle.

Electric starting, for one. Ducati obviously intends this machine to appeal to more than the cultist few. The handlebars have an inch or so of rise, while the usual cafe bike will have lower clip-on style bars or maybe actual clip-ons. The seat is long enough for two people and there are passenger pegs. The designers knew' that most sporting riders enjoy an occasional passenger, and that low bars are fine in the canyons and hellish after an hour or so just riding along.

The steering head has a damper, which isn’t mentioned in the factory literature. We simply dialed in a turn of tension and let it go at that. And the throttle has a tensioner, which was loosened all the way for the test. In theory one could use the tensioner as a cruise control. In practice, the control is a tiny thumb screw' at the bottom of the grip. The thought of keeping the right hand on the gas while tightening the knob with the other hand deterred any experiments in this vein.

The seat hinges open, for easy access to tools and air filter. Oddly, there are no helmet hooks and no storage, although a small package could be crammed into the box for the tool bag.

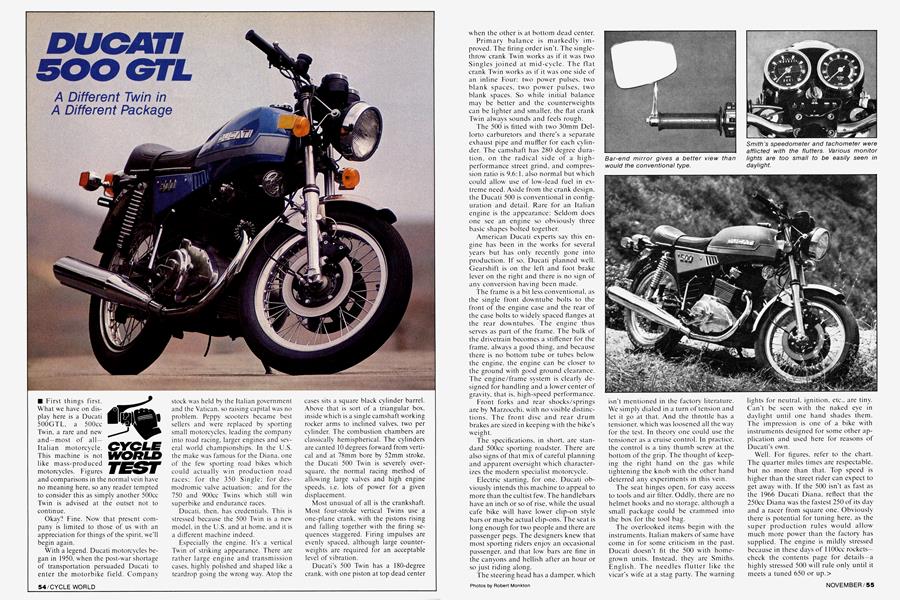

The overlooked items begin with the instruments. Italian makers of same have come in for some criticism in the past. Ducati doesn't fit the 500 with homegrown units. Instead, they are Smiths. English. The needles flutter like the vicar’s wife at a stag party. The warning lights for neutral, ignition, etc., are tiny. Can’t be seen with the naked eye in daylight until one hand shades them. The impression is one of a bike with instruments designed for some other application and used here for reasons of Ducati’s own.

Well. For figures, refer to the chart. The quarter miles times are respectable, but no more than that. Top speed is higher than the street rider can expect to get away with. If the 500 isn’t as fast as the 1966 Ducati Diana, reflect that the 250cc Diana was the fastest 250 of its day and a racer from square one. Obviously there is potential for tuning here, as the super production rules would allow much more power than the factory has supplied. The engine is mildly stressed because in these days of 1 lOOcc rockets— check the contents page for details—a highly stressed 500 will rule only until it meets a tuned 650 or up.>

DUCATI

500 GTL

$1849

More rewarding for the rational rider, the 500 starts easily, seems to stay in tune without fuss and pulls well from all speeds. Redline for extended use is 7000 rpm and 8000 for short bursts. Not high these days. The gearing has been matched to the engine, with redline and top speed arriving on the dials together. None of the performance is wasted.

Interesting, though, that in this issue are two Italian machines, from a land famous for lots of tiny cylinders working at impossible speeds, with engines that don’t rev as high as equal or larger Multis from the big factories.

(Continuing the side comments, there is also in the catalog a Ducati 500 Desmo, with the famous valve control system. It’s redlined at 8500, because the mechanical closers can keep the valves in their places at higher revs than the GTL’s valve springs can. We hear at least one of the 500 Desmos is club racing in the East although we don’t know the results.)

Stopping is excellent on any terms. The light weight helps. So does the leverage and size of the front brake, which of course does most of the work. The tests show short stopping distances and there was no drama at all. In traffic the front disc is easily modulated, as most are. So is the Ducati’s rear drum, which isn’t as common. At no time can any of our test riders recall locking or skidding the rear wheel.

Handling is the Ducati 500’s best feature. Because none of the components appear to be unusual, on the road or in the lab, the credit must go to the stiff frame and proper geometry. In town the 500 doesn’t fall in and it steers nimbly through traffic. Through fast sweepers without a trace of wobble, flick the bars side to side as you clip through the turns, no bother. Ground clearance is always there. A rider who drags a peg on this one is doing something wrong. Or careless. The ride is surprisingly light for the control the 500 has at speed. Function of weight and power. When the suspension doesn’t have to control bulk and extremes of torque, braking from speed, etc., it has a narrower range of loads in which to work and the shocks and forks can be tuned to perform properly within those ranges.

If there is a weakness, and testing procedure virtually requires at least one weakness to be found, it’s the little roadster’s lack of resistance to the air blast from passing semis, or from the crosswind coming out of a cut. The Ducati does jink about some under these conditions. The steering damper will mollify this to an extent although because the occasional dart didn’t bother us, and the light steering pleased us, we left the damper on the light side.

Is there a price, besides money? No. The seat is padded. More, the padding is round. No right angles to cut circulation. The low rise bars keep the rider’s back unbowed while allowing a forward lean into the wind. There is room, and power, enough for two adults. Sure, the passenger will be closer to the operator on the Ducati than on, say, an Electra-Glide. So pick a passenger whose, er, contours you enjoy.

The footpegs cannot be called rearsets because they aren’t set back much. Instead, they’re slightly aft of the usual touring location, which works out (for our riders, anyway) just about right. The switches can be reached without fumbling or discomfort.

Also, they work. Matter of fact, everything on the Ducati worked, when we picked it up, during the month we rode it and when we gave it back. Sad to say that isn’t always the case with a specialist motorcycle; human hands are less reliable than machines.

But perhaps human hands are the key here. What we have in the Ducati 500GTL is a smallish sporting roadster. It has a reliable engine, light and positive clutch and gearshift, good brakes and controls. It looks like what it is. There isn’t much of the famous Italian flashbike flare about this Ducati, which also means you can live with it. It begins to grow on the rider. If no more than one other motorcyclist in 10 gives more than a casual glance, the impressed and approving nod from the informed few must make up for the lack of public pizzaz.

It’s a nice little bike. People who don’t need to leap away from the light on the rear wheel, and who are confident enough in their own judgment so as not to require instant approval from the guys at the drugstore, should find the Ducati 500GTL very much to their liking. 0

Camshaft and valves live in the little house atop the barrel. Gearshift seems to have been designed for left side operation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSelling the Sizzle

November 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

November 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

FeaturesToo Much Government Is In Our Future

November 1977 By Lane Campbell -

Features

FeaturesItalian Spoken Here

November 1977 By Jean Crabb -

Roundup

RoundupThe Victory Continues

November 1977